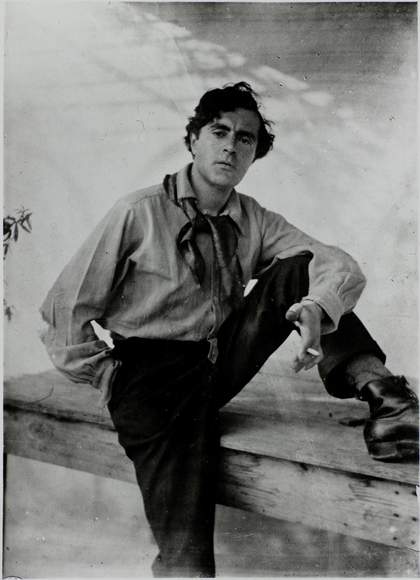

Amedeo Modigliani by an unknown photographer

Best known as a painter, before his death at the age of thirty-five, Amedeo Modigliani also created impressive sculptures and drawings. However, the legend of his troubled life and early demise - and the subsequent suicide of his young fiancée, Jeanne Hébuterne - has tended to overshadow his significant artistic achievement.

As author Arthur Pfannstiel wrote in 1929;

The life of Modigliani, wandering artist, so often resembles a legend it is difficult to determine fact from fiction

What remains of this extraordinary man is a body of work that modernised figurative painting. Often characterised by their elongated bodies and blank eyes, his subjects are distincively 'Modigliani', each telling a different story about his life and art.

Here are a few things you may not know about him ...

Modigliani is at Tate Modern, 23 November 2017 – 2 April 2018

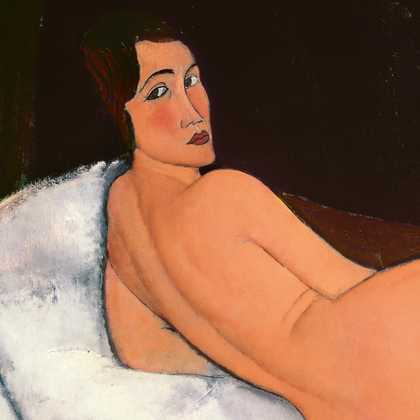

Reclining Nude 1919. Museum of Modern Art, New York

1. His nudes were very controversial

For his first and only solo exhibition, Modigliani painted a series of nudes, which are now among his most famous paintings. Legend has it that the nudes drew such a crowd around the gallery that it eventually caught the attention of a police officer. The officer was offended, not so much by their nudity as by the fact they displayed pubic hair, and promptly ordered them to be taken down. Whether or not this actually happened, the exhibition certainly caught the imagination of the public, and contributed to Modigliani's reputation as a scandalous playboy.

In addition, Modigliani’s ‘modern women’ are seen by some as a symbol of sexuality and defiance. Their unapologetic stares and poses convey women in control of their bodies and their livelihoods (models at the time earned relatively good money). This, in itself, made a real statement.

Amedeo Modigliani, Jeanne Hébuterne 1919 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

2. He loved poetry

I do not think I have ever met a painter who loved poetry so much

Ilya Ehrenburg

Modigliani was said to regularly recite Dante and other poets from memory. He also painted a number of well-known contemporary poets and writers including Blaise Cendrars, Guillaume Apollinaire and Jean Cocteau.

His favourite text was the Les Chants de Maldoror by the Comte de Lautréamont (Isidore-Lucien Ducasse) which he carried everywhere in his pocket. The reason for his obsession with this particular text may be due to the connections with his own life. Ducasse was anecdotally remembered as a ‘diseased genius’ and a ‘loner’. Modigliani may have felt that this loner poet reflected his own unpredictable moods and outsider status as an Italian Jew in Paris.

Amedeo Modigliani

Caryatid with a Vase (c.1914)

Tate

3. He drew constantly

To do any work, I must have a living person ... I must be able to see him opposite me

Amedeo Modigliani

Modigliani loved to draw from life. Although sometimes he may have used photographs for reference, more often, his paintings started with him working directly from a model. He was an obsessive draughtsman, often pulling out paper and pencil in cafes or on the street, in an exercise that has been described as ‘graphic gymnastics’. These drawings became crucial preliminaries to his paintings, as well as items he could try and exchange for goods when short of money.

Amedeo Modigliani

Head (c.1911–12)

Tate

4. His sculptures may be made from stolen stone

For a few years of his life Modigliani abandoned painting to focus on sculpture. He was even chosen to exhibit in the Salon d’Automne in 1912, a great honour for a young artist at the time. However, given his financial difficulties, biographers have wondered how Modigliani managed to afford the expensive materials needed to make these works.

It may be that, like a number of other sculptors at the time, at times he ‘borrowed’ stone to support his practice. Montparnasse, where he lived, was one of the last areas of Paris to be renovated, with a wealth of limestone set aside for its building sites. It is possibly not a coincidence that Modigliani’s series of Heads are carved from the same type of rock.

5. He wasn’t afraid to speak his mind

In 1918, Modigliani and his partner, Jeanne Hébuterne, visited the famous Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Probably believing Modigliani would enjoy some banter, Renoir confided that he did not believe a painting of a nude was finished unless he felt the urge to slap her backside. Instead of laughing along, Modigliani cut the conversation short by replying bluntly ‘I don’t like buttocks’.

His alleged answer is an example of how Modigliani lived on his own terms, not feeling the need to be deferential to other, more established, individuals. It could also be read as a sign of respect for his female models. Despite his many flaws, when you look at Modigliani's portraits, they can be read as being painted with empathy and emotion.

Amedeo Modigliani, The Little Peasant c. 1918 © Tate

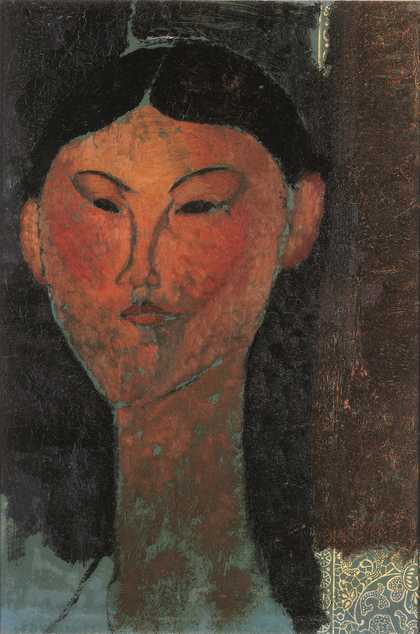

Amedeo Modigliani, Beatrice Hastings 1915. Private Collection