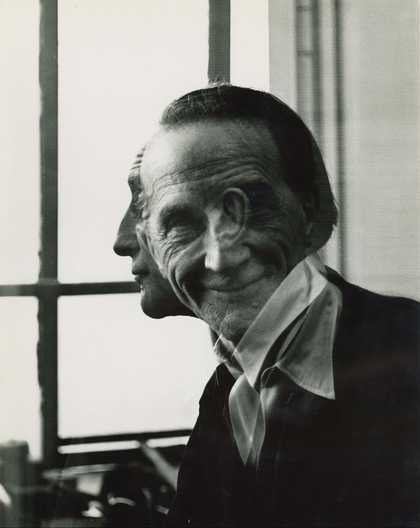

Victor Obsatz, Portrait of Marcel Duchamp 1953

Courtesy Moeller Fine Art, New York

He is known as the godfather of conceptual art, yet Marcel Duchamp was also a great admirer of the Pre-Raphaelites, and had strong affinities for their craftsman-like approach and their 'tortured explorations of sex, chastity and desire'.

It is now a century since a white ceramic urinal entitled Fountain, with ‘R. Mutt 1917’ daubed on the upper edge in black paint, was submitted to the New York Society of Independent Artists. Set on its back, reclining like a nude, its place in Marcel Duchamp’s œuvre has loomed ever larger, so that it now eclipses all else, like van Gogh’s severed ear.

Fountain – or rather, The Urinal, as some call it – is often considered the most influential art- work of the 20th century, even though its international notoriety dates only from the mid-1960s. Having been rejected by the Society, prompting Duchamp to resign, it was photographed by Alfred Stieglitz in front of a painting, and another photograph of about 1918 shows it suspended from the ceiling in Duchamp’s New York studio. It was permanently lost when he moved from New York and only started to become partially visible again when he made miniature replicas for his edition of ‘collected works’, Box in a Valise 1935–41. But its real second wind came when replicas were made in 1950, 1963 and 1964, coinciding with the rise of neo-dada, pop and conceptual art.

Its post-war novelty has tended to put it in a splendid/squalid isolation that has stripped it of its cultural moorings – both its relationship to Duchamp’s other work, and to 19th-century art and culture. Most people now assume Duchamp is Mr Ready-Made Urinal and little else. British artist Grayson Perry’s 2014 book Playing to the Gallery, based on a BBC radio lecture series, is all too typical. He sees the art world’s rediscovery in the 1960s of Duchamp’s urinal as the beginning of the end for handmade art. It was ‘arrogant’ and ‘dictatorial’ when Duchamp ‘decided that anything could be art [and] got a urinal and brought it into an art gallery’. For Perry, the ‘final irony’ is that when replicas were made, ceramicists had to create them because the 1917 type was obsolete.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain 1917, replica 1964, porcelain, 36 x 48 x 61cm

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017, photo: Tate Photography

Despite being the latest incarnation of Duchamp’s transvestite alter ego Rrose Sélavy, you would never guess from Perry’s account that Duchamp wore a variety of artistic clothes. He never repudiated the handmade. Indeed, of all the great 20th-century artists, he was the most obsessional and original craftsman by far, a keen admirer of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, of anonymous artisans and pre-industrial machinery. Duchamp is not just the author of a few ready-mades, but of many more painstakingly-mades. His most ambitious works, The Large Glass 1915–23, Box in a Valise and Étant donnés 1946–66, are meticulously assembled multimedia craft masterpieces. The Large Glass borrows aspects of stained glass, painting, sculpture and joinery. Its machine imagery is pre-industrial (a watermill, scissors, sieves, chocolate grinder). The only modern French artist he claimed to admire was the manically methodical pointillist Georges Seurat, ‘who made his big paintings like a car- penter, like an artisan’. Duchamp came closer to William Morris’s craft aesthetic and respect for ‘humble’ handmade objects than you might think.

So there were two Duchamps... So Duchamp was Janus- faced... So what? What common ground can there possibly be between a urinal and the English Arts and Crafts Movement? Doesn’t a mass-produced urinal pisse with abandon on the past? Well, not quite. A key connecting thread is a shared conception of the artist as someone who aspires to chastity both in relation to style and lifestyle. Indeed, in the 19th century chastity – in theory if not in practice – played a role comparable with that of modernist purity in the 20th century. Chastity – or at the very least sexual moderation – was believed to underpin genius, with erotic energy channelled into art. Duchamp may have had his tongue perpetually in his transvestite cheek (to adapt the title of his 1959 self-portrait), but he was consistent in his erotic preoccupations – and many of these were shared with the 19th-century avant-garde brotherhoods.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Raphael and the Fornarina 1814, oil on canvas, 64.8 x 53.3 cm

Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum, photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College

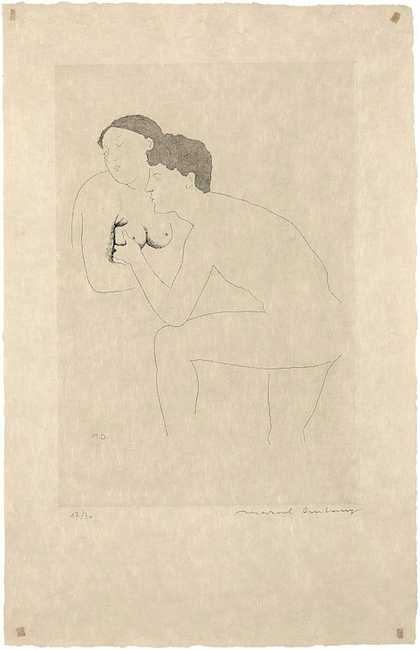

Marcel Duchamp, Selected Details After Ingres II 1968, etching with aquatint on paper, 34.5 x 23.6 cm

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London/Estate of Marcel Duchamp, photo © 2016 Christie's Images Limited

There was, in fact, nothing random about the choice of a urinal. Let’s look again at the first two authorised statements justifying Fountain. Stieglitz’s photograph was taken for the second issue of the New York dada magazine The Blind Man, whose editorial – undoubtedly written by Duchamp – mounted a terse defence: ‘Now Mr Mutt’s fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bath tub is immoral ... Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it ... [he] created a new thought for that object. As for plumbing, that is absurd. The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.’

The intrinsic morality of the object is amplified in an accompanying essay by the writer Louise Norton, ‘Buddha of the Bathroom’, obviously written with Duchamp’s input. The title emphasises the chaste anthropomorphism of the piece, equating its appearance to that of a seated Buddha – who was chaste. Norton points out the multifariousness of a modern man’s roles in society, so he is never only a husband – he also has non-sexual roles as father, worker, etc. Sadly, she writes, the committee who rejected Fountain practise ‘meticulous monogamy’ in relation to art and cannot see the virtues in anything else:

'Yet to any “innocent” eye how pleasant is its chaste simplicity of line and colour! Someone said, “Like a lovely Buddha”; someone said, “Like the legs of the ladies by Cézanne”; but have they not, those ladies, in their long, round nudity always recalled to your mind the calm curves of decadent plumbers’ porcelains?’

Chaste simplicity and calm curves are neoclassical stylistic categories that were most powerfully articulated in relation to white marble sculpture, and to line drawings by artists such as the British sculptor-engraver John Flaxman, praised for the correctness and ‘vestal purity’ of his work. Unbridled colour and sensuous brushwork were frowned upon. Ingres, a maker of refined line drawings, dramatised the battle of styles – and lifestyles – in his famous series of six paintings of Raphael in his studio with his Roman mistress La Fornarina (the baker’s daughter), created from 1814 to 1840. Duchamp would have seen some of these in the great Salon d’Automne of 1905, where the fauves made their appearance alongside retrospectives of Manet and Ingres; he later made line drawings in homage to Ingres. Raphael sits at his easel with the yeastily voluptuous La Fornarina sitting on his lap. But he turns away from her to look at the clean linear under-drawing for his portrait of her on his canvas. Here, the love of art triumphs over the love of women; demure line drawing over sensuous oil painting. Some 19th-century critics, however, decided that Raphael’s art as well as his sex life became decadent in Rome, so they favoured the more ‘primitive’ and ‘linear’ art from his early years in Tuscany – what Mary Shelley, in 1840, called ‘his first and most chaste style’. Members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848, were really the Pre-Roman-Raphaelites. They idealised medieval courtly love, where desire remains unconsummated. Meticulous artwork and craft, often collaborative, was a spiritualised substitute for sex.

After Edward Burne-Jones, The Legend of the Briar Rose - The Prince Enters the Briar Wood 1892, photogravure by Thomas Agnew & Sons Ltd, 41.5 x 82.7 cm

Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

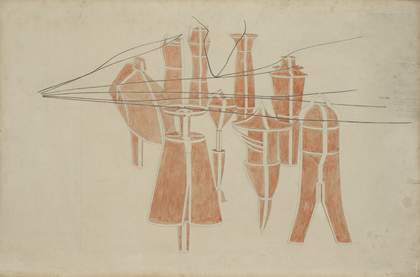

Marcel Duchamp, Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, No. 2 1914, graphite and watercolour on paper, 66 x 99.8 cm

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London/Estate of Marcel Duchamp, photo: Yale University Art Gallery

For the rest of the century the implications of this momentous and often misogynistic moral bind would be played out, with artists ignoring lovers and wives, sublimating their sexual energy in their art. Balzac believed he lost a novel every time he had sex, leading van Gogh to write to Émile Bernard: ‘Ah, Balzac, that great and powerful artist, already told us very well that for modern artists a certain chastity made them stronger.’ Nietzsche, one of many philosophers to advocate chastity, believed Raphael, like many great artists, had an overheated sexual system, but refused ‘to expend himself in any casual way’. The same seems to be true of Duchamp. He claimed to be anti-marriage rather than anti-feminist, but his work is saturated in 19th-century male anxieties about the ‘woman question’.

Duchamp’s repudiation of what he called ‘retinal’ painting designed to appeal purely to the eye, and his switch at the time of The Large Glass – real title The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even – to diagrammatic line drawing, emerge from this very debate. So too does Fountain with its clean antiseptic contours. In a note written in 1914, he observed: ‘One only has: for female the public urinal and one lives by it.’ Modern man rejects modern woman and finds objects – such as the chastely anthropomorphic urinal – to fetishise instead (and in which to insert their penis for non-sexual purposes). One would never, of course, dream of touching a urinal. Object fetishism was defined as a condi- tion by psychiatrist Alfred Binet in 1887.

Duchamp’s interest in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood did not only stem from their idealisation of the male-only artistic collective, their commitment to craft as well as fine art and the hallucinatory intensity of detail, colour and con- tour. He was equally impressed by their tortured explorations of sex, chastity and desire. Their complex storytelling would have appealed to an ‘anti-retinal’ artist yearning for painting that was ‘religious, philosophical, moral’. Duchamp, who trained as a printmaker and had made satirical illustrations for magazines, would have been familiar with English Pre-Raphaelite art from superb-quality prints, and from art magazines such as The Studio and Gazette des Beaux-Arts. He went on holiday with his sister to Herne Bay, Kent, in 1913, and there may have been more undocumented English visits. Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), widely considered a Pre-Raphaelite, but actually an associate of Morris who painted furniture and made stained glass, was a crucial influence: The Golden Stairs 1880, with its self-contained innocent sisterhood of descending women, drawn in a severely rhythmical style that is a hybrid of Flaxman and Botticelli, is often cited as precursor to Duchamp’s two versions of Nude Descending a Staircase 1912. Burne-Jones’s extraordinary Briar Rose 1885–90 series, each picture put together like a big machine with harsh streamlined contours and looping patterns, is equally important. It tells the story of Sleeping Beauty at the end of her century-long (chaste) slumber, and almost certainly influenced the gestation and subject matter of the The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Golden Stairs 1880, oil paint on canvas, 269.2 x 116.8 cm

Photo © Tate

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) 1912, oil paint on canvas, 147 x 89.2 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, © Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London/Estate of Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp’s ‘bachelors’ – the nine ‘malic moulds’ resembling suits of armour – are suspended and dangerously caught up in the machinery of its lower section. This entrapment frustrates their attempts to reach the bride in the top section. They were mapped out in a series of drawings of 1913–14, Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, which recall Burne-Jones’s depiction of the androgynous knights who had pre-maturely attempted to get through the tangled rose hedge – more like barbed wire – that grew up around Sleeping Beauty’s castle when her slumbers began. They came to court her, but five lie dead on the ground with their shields hanging entwined in the hedge, while a sixth, who has arrived when she and the rest of the royal palace are due to wake up, is still struggling to get through. Duchamp called his masterpiece a ‘delay in glass’, and this too may have been inspired by the sexual frustration and suspended animation of the Sleeping Beauty story. A similar conceit propelled the one-mile tangle of string stretched throughout a surrealist exhibition in New York in 1942, blocking the path to the exhibits.

In a 1966 interview with Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp referred to the Pre-Raphaelites during a discussion of changing tides in taste: ‘Look at the Pre-Raphaelites: they lit a small flame, which is still burning despite everything. They aren’t very well liked, but they’ll come back – they’ll be rehabilitated.’ The Pre-Raphaelite light he must have had in mind was William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World 1851–3. This is the catalyst for Étant donnés, which he worked on in secret for 20 years. Hunt’s arched painting shows Christ standing in a garden in a white priestly robe holding a lamp, knocking at a closed door overgrown with ivy: if anyone opens the door, Christ will sup with them. The viewer/voyeur of Étant donnés stands at a battered old arched wooden door which lacks a handle, and through peep- holes sees a naked female lying akimbo in undergrowth, her left hand holding a lamp aloft. The hallucinatory intensity of the scene is thoroughly Pre-Raphaelite. Hunt paired his picture with The Awakening Conscience 1853, where a ‘fallen’ mistress realises the error of her ways as she is bathed in leaf-dappled sunshine pouring through the window. Duchamp’s awakening sleeping beauty seems to have seen and grasped the light. She opts for a vestal virgin life in nature – untouchable, inviolate and free.

William Holman Hunt, The Light of the World 1853, oil paint on canvas, 121.9 x 61 cm

Reproduced with the permission of the Warden, Fellows and Scholars of Keble College, Oxford

Marcel Duchamp, Étant donnés: 1o la chute d'eau, 2o le gaz d'éclairage... 1946–66, mixed media, 242.6 x 177.8 x 124.5 cm

Philadelphia Museum of Art, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London/Estate of Marcel Duchamp

James Hall is Research Professor at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton. His books include The World as Sculpture 1999, where he first wrote about Duchamp, and The Self-Portrait: a Cultural History 2014. He is writing a book on Sex, Chastity and Genius.