At a time when the borders between lands are continually being disputed, what does it mean to move across countries, to change nationalities and to settle in a new place? Some of us migrate by choice, others are forced to flee for our own safety.

Visitors from across the world come to Tate Modern to see international art, bringing with them their own life experiences and stories. Migration is a prevalent theme throughout the artworks on display. Artists either address it directly, or we can bring it to a work through our own interpretations.

Here a selection of contributors from Tate’s staff and its wider community come together to share the artworks at Tate Modern that allow them to reflect on what it means to migrate. These are personal reflections that speak less from a knowledge of art history and more from the act of experiencing art.

To begin this walkthrough, make your way to Level 2 of the Natalie Bell Building. You can download a map of Tate Modern to help you navigate. On Level 2, you will find two free displays. Start with Artist and Society. Art in this display shows how artists responded to their political and social contexts.

Artist and Society

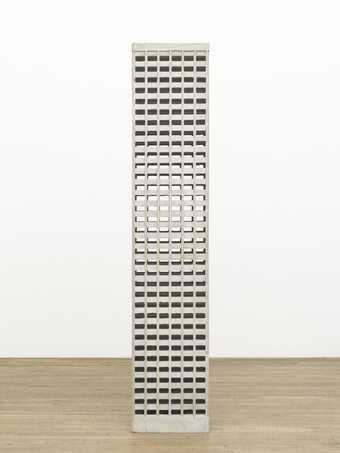

Marwan Rechmaoui

Monument for the Living (2001–8)

Tate

Monument for the Living 2001–2008

Marwan Rechmaoui

Buildings are often at the heart of refugees’ troubles. Cities and homes are reluctantly left behind while new shelter is desperately sought. Looking at this sculpture I am reminded of how cities such as Beirut, during its civil war, were left empty and hollow by refugees fleeing conflict. At the other end of this process, I have met many refugees settled into empty houses caused by deindustrialisation in places like Middlesbrough and Sheffield. Though this sculpture could symbolise the absence of life caused by war in once thriving communities, personally I am reminded of all the refugees I have met breathing new life into towns and cities here in the UK.

Interpretation by Michael Raymond

Uzo Egonu

Woman in Grief (1968)

Tate

Woman in Grief 1968

uzo Egonu

I relate to Egonu’s status as a migrant ‘looking back’ to Nigeria with anxiety, as he painted this picture during the Biaffran war. I also have looked anxiously back to Tunisia, the land of my forefathers, for a sense of self and direction. I hear with a broken heart news of Tunisian struggles and governmental injustices since the 2011 Arab Spring. I relate to the woman in the picture, doubled–over in pain, neither here nor there, caught in limbo between living here but being spiritually and psychically attached to our motherland.

Interpretation by Cina Aissa

Gordon Bennett

Possession Island (Abstraction) (1991)

Tate

Possession Island (Abstraction) 1991

Gordon Bennett

As an Indigenous Australian artist, Gordon Bennett may not be a migrant, however Possession Island (Abstraction) demonstrates the tensions that impact cultural minorities due to colonial migration. Our idea of national identity is reversed when we think of colonial migration. Those who see the land as home are faced with the threat of displacement and a loss of culture. Those who are new to the land, come with an undeserved position of authority. We see the single human representation of the Aboriginal community, in a Samuel Calvert’s engraving of Captain Cook, hidden behind the colours of the indigenous flag. The abstraction of colour turns the servant faceless. Carrying a tray of drinks, he is a tool for the use of the colonisers. Australia, like many countries, has a long history of reducing others to voiceless symbols. It has enforced standardised identities on cultures without consent and incarcerated refugees on the islands of Manus and Nauru under false narratives of threat. It is endemic of the fragility that comes with colonial migration. There is a simplifying of the diversity of history at play in order to give power to the privileged.

Interpretation by William Dante Deacon

Teresa Margolles

Flag I (2009)

Tate

Flag I 2009

Teresa Margolles

This dark and dusty flag is soaked in blood and dirt from violence on Mexico/US boarders. For me, it represents not just the location it draws from, but a statement of the incredible bloodshed that is familiar with every history tied to European colonialism and conquest. For me, a blood and dirt stained flag is probably more familiar to a history I understand, rather than the British, Indian or Pakistani flags I see. When I look at Margolles's artwork, I see a flag of Partition and the violence that it created and still creates – a violence that the perpetrators never reflect on.

Interpretation by Hassan Vawda

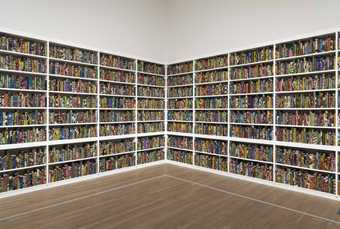

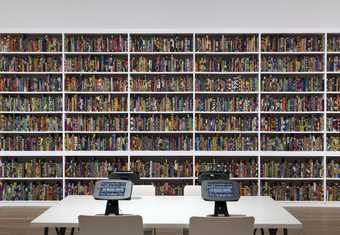

The British Library 2014

Yinka Shonibare

Migration to me feels ‘normal’. I am aware that I am saying this from the privileged position of having had a choice. Hardly a migration, yours, some may say. Yet, I chose to migrate language, historic memories and cultural context. To me, not to belong feels like an open place to be in. This may not be the same for others. Increasingly identities of belonging appear to be forced upon me, adjectives I should use to classify myself, nationality being but the most obvious one. The books in Yinka Shonibare’s The British Library carry the names of people with a direct experience of or involvement in the discussion around migration on their spines, mine being one of them. I could not feel more at home than seeing my name within the company of so many fellow migrants from different backgrounds. Books need titles to be catalogued, but be allowed to remain open to new readings.

Interpretation by Achim Borchardt-Hume

What other artworks in this display make you think of what it means to migrate? Once you’re done here, walk across the concourse to In the Studio. This display offers a chance to see the processes involved in making an artwork. Think about how artists may have changed their processes when they migrated by adopting different techniques and styles from their new homes.

In the Studio

Red on Maroon 1959

Mark Rothko

'I paint very big to be intimate'

Rothko's murals were the first artwork that I saw in the early 1970's on a school trip to Tate Britain. Now, fifty years later, I sit surrounded by them and try to listen to their whispers in a very noisy world. I think Rothko wanted a painting that somehow includes what everyone feels about everything, whilst creating art that would provide a place for him. He was combative, ambitious and intense. He desired success but struggled with guilt over these desires and was vulnerable to despair. These conflicts formed the genius of Mark Rothko.

I grew up in the East end of London, surrounded by many Jewish families who I retain close contact with. Rothko and his family arrived in New York at a time when anti-Semitism was globally endemic. He fought for recognition. To create works of art in that climate of oppression, to me is inspiring. This was an artist who was forced to move from Russia because of his religion and make a name for himself. Anti-Semitism still raises its ugly head, and it is not just Jews, but many others as well who have to leave their homes and families because of prejudice. What will be the outcome for them?

Interpretation by Wendy Kenny

Piero Manzoni

Achrome (1958)

Tate

Achrome 1958

Piero Manzoni

As a mixed race girl growing up in suburban England, I saw very little of myself around me. Most of what I heard, saw, felt or read was white. Moving to London opened my eyes to what it felt like to truly see yourself. Not just hair shops or braids, but a whole spectrum of Blackness.

On looking at Achrome and its total absence of colour, I think of my Caribbean grandparents. I think of the Windrush generation travelling to London in the late 50s – around the same time Manzoni created this piece – and the history of unbelonging.

Interpretation by Rachel Noel

Sir Anish Kapoor CBE RA

Ishi’s Light (2003)

Tate

Ishi’s Light 2003

Anish Kapoor

Speaking about Anish Kapoor as an artist who wasn’t born in Britain but came here to study and made London his home, brings me back to my own journey.

Coming from a migrant background has always been a core element to my art. Throughout my journey as an artist, I have strongly realised that our background not only makes us who we are, but it is an ever-present part of our identity as artists. Standing in front of the work Ishi’s Light large sculpture, three-metre tall shaped as an egg shell Its simplicity and minimalism is so intriguing. The work speaks so much to the viewer, yet immediately does not reveal its full glory. Instead, the viewer reflects on the inside reflection and builds an intimate relationship with the work.

Having in mind the title Ishi’s Light, a work dedicated to his son, we immediately think of love, devotion, protection. The outside rocky texture renders strength, protection and security. Its matte finish it reminds me of a belly of a pregnant woman. The inside is smooth, glossy and genuinely inviting. Its dark red colour reminds me of the colour of the placenta; the nourishment and protection of the child while still in the womb.

As a mother myself, I try to always represent my emotions and feelings of love, light and uncertainties, when working on ideas about my own children . It is this work that reflects the warmth and safety a parent wishes for their child. Standing in front of this Anish Kapoor work is a unique reflective observance between the art and the artist; the power of art and the meanings we try to give to the most complex feelings in life.

Interpretation by Alketa Xhafa Mripa

When you have finished, take the escalator or lift to Level 4 of the Natalie Bell Building. Here, you will find Media Networks – a display that reflects on how art has changed in response to the growing technologies of our age.

Media Networks

Cildo Meireles

Babel (2001)

Tate

Babel 2001

Cildo Meireles

I grew up in my mother’s country and moved, once adult, to my father’s country. Since the day I was born, I’ve heard the blend of both their languages, batted back and forth above my head. Learning to talk, I didn’t always recognise which words belonged to which and weaved them together, making my own new language. I added words from other dialects that I’ve sought out, creating an animated, comforting cacophony. This same cacophony speaks to me from Babel. Cildo Meireles’ work may feel busy and disorientating to some, but to me it feels familiar. Every time I step into its blue shadow, it feels like home.

Interpretation by Gabrielle Young

Sonia Delaunay

Triptych (1963)

Tate

Triptych 1963

Sonia Delaunay

Sonia Delaunay always struck me as a dreamy figure. A star of the Parisian avant-garde, travelling in circles of artists and poets, she was the height of sophistication—particularly to a teenage girl growing up in America, and the daughter of Polish migrants.

I’d often dream of my own escape back to the ‘old world’, an idealised version of the place my parents fled in the 1980s. The Europe I envisioned was an antidote to the drab realities of the Soviet Bloc and American suburbia. It often took the form of London, or Paris, and it was brimming with urbane, colourful characters like Delaunay.

Little did I know that Sonia Delaunay was born Sonia Illinitchna Stern to a Jewish family in Ukraine. The cosmopolitan image I’d marvelled at had a migrant identity at its core, and learning this changed the way I saw her work, and her persona—and helped me come to terms with my own. Looking at Delaunay’s work now, I see the bright colours of traditional Ukrainian dress bound up in the visual language of Cubism, and the many facets of her identity linked in one beautiful whole.

Intepretation by Camille Gajewski-Richards

Martin Creed

Work No. 232: the whole world the work = the whole world (2000)

Tate

As you leave Media Networks, travel across the concourse. Here, you will see Martin’s Creed Work No. 232 and Rudolf’s Stingel’s Untitled artwork that looks like an orange carpet. Can you think about these works in the context of migration? What do Creed’s words mean? Try making a mark on Stingel’s artwork and then wipe over it. Watch as it is easily erased. Can Stingel's artwork be seen in the context of migration?

On the same level is our next display, Materials and Objects. This display focuses on artists who have used unusual methods and materials in their artworks.

Materials and Objects

El Anatsui

Ink Splash II (2012)

Tate

Ink Splash II 2012

El Anatsui

El Anatsui was born in Ghana in 1944, and trained as a sculptor at university in Kumasi, Ghana’s second largest city, before accepting an invitation to teach at the University of Nsukka, Nigeria in 1975. That movement from one country to another is perhaps a story less told, but full of historical weight. In 1969, Ghana expelled Nigerians from the country: Nigeria reciprocated in kind in 1983. One million Ghanaians without the correct immigration documents were expelled. ‘Ghana Must Go’: the red, blue & white plastic chequered bags are still commonplace. My mother explained to me that in Ga, a Ghanaian language, ‘anatsui’ means patience. Perhaps the shimmering bottle caps that make up this artwork present us with a multitude of metaphors. Think of all of the hands those bottles and caps passed through before reaching us. All of those lives, all of those stories. One builds with whatever is at his or her disposal. You can make something out of what appears to be very little: one man’s 'junk' is another man’s treasure.

Interpretation by Vanessa Peterson

Marcel Duchamp

Fountain (1917, replica 1964)

Tate

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2025

Fountain 1917, replica 1964

Marcel Duchamp

When people move, the world moves too and these movements are apparent in the realms of art. Duchamp’s work The Fountain came into my periphery when I was nineteen years old in Canada, I had learned about his work in my first contemporary art class (which was also my last). I was completely obsessed with the nuances of Dadaism, the act of taking something and flipping it on it’s head so it had new meaning and therein changing societies understanding of what the possibilities of meaning could be. When I moved to the UK and visited Paris, I went out of my way to find it in at the Pompidou. I used to stare at it to connect myself to one of the most historical movements in art, to stare at something the art world called one of the most significant works of the 20th century and what people around the world considered to be simply a urinal. Every time I look at it, it inspires me to turn what I think on its head and look for the other side. Maybe that’s what our forefathers did – search for a new meaning on the other side of our world.

I thank Duchamp for making me migrate. I see a different version of myself and redefine everything I think things can be. This piece has single handedly influenced the pursuit of my dreams and inspired me to travel the world and cross many cultural and internal boundaries and in the end bring me back to the land of my forefathers.

Interpretation by Ryan Lanji

As you leave Materials and Objects, you’ll see a bridge on the right-hand side. This will take you across to the Blavatnik Building, where you can discover more artworks. As you cross the bridge and move from one building to the other, think about the act of travel. What feelings are triggered when you move from one place to another? Are bridges methods for transportation or can they be destinations in themselves?

As you arrive in the Blavatnik Building, feel free to look around. There are free displays, like Living Cities, where your exploration of migration can continue.

Biographies

Achim Borchardt-Hume was born in Düren, Germany and lived in Rome before settling in London in 1992. He works as Director of Exhibitions and Programmes at Tate Modern.

Alketa Xhafa Mripa is a London-based conceptual artist and activist from Kosova. As a bold messenger for activist art, Alketa is a passionate advocate of the truth, and human rights. Empowering women living in oppressive societies, she shares with the world a deep emotional response to the reality in which she exists. Alketa became a refugee when the 1998-1999 Kosovo war broke out and came to London in 1997 to study Fine Art at Central Saint Martin.

Camille Gajewski-Richards is a writer and creative producer in the arts, and is currently Producer for Tate Exchange.

Cina Aissa is a French Tunisian mother, storyteller and multi-disciplinary artist currently working in London. She believes in using and producing art as a tool for resilience and self-soothing. She works at Tate as a Learning Assistant.

Gabrielle Young works in the Technology department at Tate.

Hassan Vawda is the Guides Coordinator at Tate and a co-chair of Tate’s BAME network. He is also an artist involved in programming and projects across multiple disciplines and an Aziz Foundation Scholar studying Community Development, looking at inclusion/exclusion within cultural and creative spaces, particularly faith-based creative expression.

Michael Raymond is an Assistant Curator at Tate Modern and an ex-member of Student Action for Refugees (STAR) in Sheffield.

Rachel Noel works with artists, collectives and partners to produce programmes with and for young people, particularly those from under-represented backgrounds, as Curator: Young People’s Programmes at Tate Britain and Tate Modern.

Ryan Lanji is a Fashion Curator and Producer of HUNGAMA, East Lonon’s queer Bollywood hip hop night. He has worked with Tate for their TateLates series.

Vanessa Peterson is an editor, photographer and occasional writer currently working as a Research Producer at Tate. Her research interests focus on the relationship between the word and image, especially representations of race and gender.

Wendy Kenny is one of the volunteer guides at Tate.

William Dante Deacon is a writer from Adelaide, South Australia. He has written significantly on the political philosophy of citizenship and displacement, and produces short fiction for magazines and exhibitions. He also works in the cafe at Tate Modern.