Could it be that it’s just an illusion, or have some recent exhibitions been playing tricks on our eyes? The Hayward Gallery’s Eyes, Lies & Illusions showcased a vast collection of optical illusions dating from the Renaissance to the present day, including shadowplay, distorting mirrors, dioramas, magic lanterns, a camera obscura and a perspective bending Ames Room. Meanwhile, the synaesthetic intermingling of the senses described in Charles Baudelaire’s poem Correspondences 1857 was evoked by the optical trickery of Brion Gysin’s hallucinatory Dream Machine 1960–1976 on display at the Pompidou Centre’s Sons & Lumières. A history of sound in twentieth-century painting, film, installation and video, the Paris show devoted much attention to the kinetic experiments of Modernists such as László Moholy-Nagy and abstract animators including Oskar Fischinger and Walt Disney. Complementing this curatorial tendency, Summer of Love: Art of the Psychedelic Era at Tate Liverpool proposes to illuminate the counter-culture of the late 1960s while renewing consideration of many neglected artists.

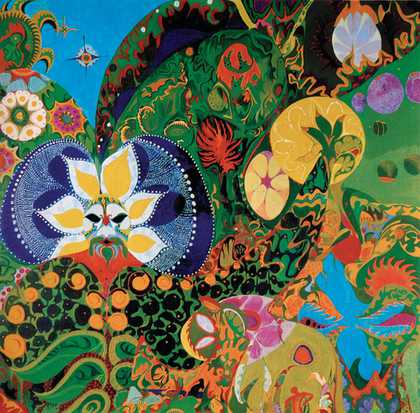

Although the word psychedelic is used to describe all manner of colourful exoticisms, in its heyday it was primarily a broadening of the sensualist concerns of twentieth-century artists. Since hallucinations and synaesthesia were induced by powerful synthetic drugs, psychedelic art has often been seen as an extension of the laboratory into the creative process. In 1967 the effect of psychedelic artists tripping on modern hallucinogens was studied by psychologist Stanley Krippner at the Dream Laboratory in Brooklyn. One of his subjects was Isaac Abrams, owner of the psychedelic Coda Gallery. Abrams thoroughly embedded his work in the heightened sensory awareness and harmonious sensation of creative satisfaction induced by hallucinogens. Krippner noted in the artist’s dreamlike cosmology and saturated colour schemes recurrent juxtapositions of eidetic images – mental images that appear to be in a real physical space. His paintings were not mere synthetic imaginings, they were portals to ‘core’ experiences unlocked by hallucinogenic keys. By aiding and abetting psychedelic experiences through his work, he hoped to enable a sense of fusion between art, mind and body and, by extension, reveal the essential unity of all things.

Like heroic Modernists in the early twentieth century, psychedelics such as Abrams made grandiose gestures and bewilderingly idealistic claims for their work. While Abrams made a conscious effort to develop a psychedelic practice, intimately bound with the political and cultural ambitions exemplified by gurus such as Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary, many artists branded as psychedelics just drifted into (or out of) focus. A student of Fernand Léger in 1950s Paris, Abdul Mati Klarwein began painting in what came to be known as a psychedelic style before experimenting with hallucinogens, sourcing his tremendously detailed imagery in early Netherlandish painters such as Hieronymus Bosch, Italian Renaissance art, Surrealism and Indian tantric art. He painted in a hyper-realist manner inspired by his friend Salvador Dalí, whose famous ‘paranoiac-critical method’ can be seen in Klarwein’s love of visual games involving mirroring and entanglements of abstraction and representation.

At the turn of the 1970s, Klarwein’s loft in New York was a psychedelic Mecca visited by new pagans such as Jimi Hendrix, Timothy Leary and Miles Davis. His paintings soon became famous as LP sleeve designs for Davis’s Bitches Brew 1969 and Live-Evil 1971 and Carlos Santana’s Abraxas 1970, his cosmic subject matter and Dalíesque pictorial games echoing in album covers by peers such as Hipgnosis. However, as with many psychedelic artists who were recognised through their poster and record designs, this led him to be shunned by the gallery system. Despite his illustrious astro-black pop credentials (Andy Warhol claimed that Klarwein was his favourite painter), his tribal dodecahedrons and erotic new age ‘inscapes’ went entirely against the cool, literal tendencies of the period.

The latest exhibitions coincide with artists’ renewed interest in optical experiments; be they based on the relationship between sound and vision, drawing games, the cultural fallout of psychedelia, or the uneasy impact of new imaging technologies. Pierre Huyghe’s L’expédition scintillante, Acte 2 ‘Untitled’ (Light Box) from 2002, which featured in Sons & Lumières, exploits our inclination to look for meaningful patterns in abstract visual noise. A miniature concert stage veiled in dry ice bathed by coloured lights that automatically adjust to provide ambience for Eric Satie’s Trois Gymnopedies 1887, Huyghe’s installation performs the spine-tingling mantra of anticipation experienced at the start of a performance.

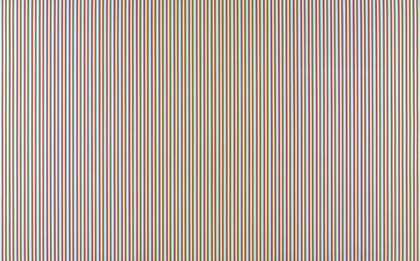

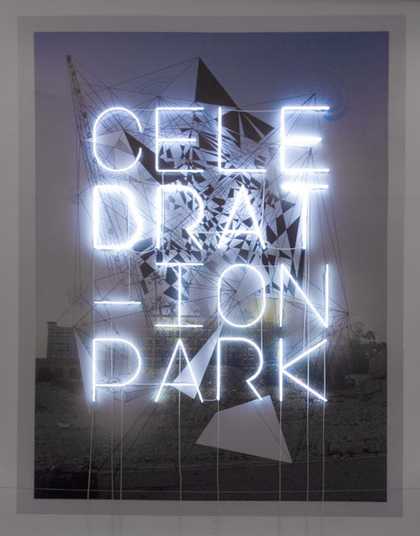

Elements of 1960s psychedelia and Op Art can clearly be seen in the work of Jim Lambie, who is renowned for his busy sticky-tape installations that mix the floor hugging minimalism of Carl Andre with the strobing optical effects of Bridget Riley. Eva Rothschild’s work reconstructs the creative and utopian potential of psychedelic art as a belief system that continues to manifest itself today in new age mysticism. Rothschild is no psychonaut though: the objects and rituals evoked in her work do not provide the key to existence, yet they are not so different from artworks in that they encourage a similar leap of faith. The invocation of the sublime in new age culture is certainly mystifying, but it is just as messy and potentially deceitful as declaring something to be a work of art.

This suggests that taste has a role to play in regulating the incursion of psychedelic culture into contemporary art. Joanne Tatham and Tom O’Sullivan’s Resurrection with Three Forms 1998 takes hippy handcrafts as a point of departure, using an enormous tie-dye as the backdrop to an exhibition of paganesque ceramic works. New age aesthetics were not welcome in the corporate contemporary art world of the 1990s. Titles such as Think Thingamajig and Other Things 2004 are reminiscent of logical problems as they might have leapt from the pen of C.S. Lewis. In their No, this is the thing that has reached the limit conditions of its own rhetoric 2003 two top-hatted gentlemen seated on Modernist chairs play chess. The image recalls a ‘devil’s fork’, an impossible space made famous by M.C. Escher’s Ascending and Descending 1960. On closer inspection we see that the image is a double bluff. There is no puzzle. Illustrated in strict perspective, the gravity-defying characteristics of Gerrit Rietveld’s Z-Chair 1934 and Marcel Breuer’s cantilevered tubular steel Cesca Chair 1928 only imply visual trickery.

Tatham and O’Sullivan’s Inner becomes outer and outer becomes other, or, You’ve gotta get into it to get out of it 2002 transforms the ambiguous face/vase figure into a three-dimensional spectacle, robbing it of its ambiguity. A checkerboard floor from an Ames Room illusion is propped up against a wall, destroying the perspectival deception. Like much of their work, this points us in a number of different cultural directions. A notable precedent is David Lamelas’s 16mm film A Study of the Relationships between Inner and Outer Space 1969, which analyses social and architectural relations within and without an exhibition space. The last part of the title refers directly to psychedelic warlords Hawkwind, shades of mystery black flowing like molasses. Is this Spinal Tap, a 3D Hipgnosis sleeve, the sculptural equivalent of progressive rock? By being transferred to the same space that we occupy, the gestalt illusion is derided as a cheap fiction. Just as the gallery is de-mystified in Lamelas’s film, Tatham and O’Sullivan’s installation is merely a stage set that we can walk around; we can move in and out of the illusion as we see fit. However, these artists aren’t cynics. While we are given ample opportunity to mock this grandiose statement, we are also encouraged to participate in the fiction. Expectation is all. We can only see if we think, we will only get something out of it by getting into it.

This invitation unites the psychedelic illusions with those found in the 1990s when recreational drug-led acid house and techno scenes were illustrated by infinitesimal fractal geometry. Aided by the increase in computer processing power, Mandelbrot Set imagery was an electronic update of tie-dye, a time-based virtual space in which ravers could wallow. Run at high speed, chaos patterns mapped synaesthetically on to acid house; slowed down, they were the visual equivalent of the chill-out room. Chaos patterns illustrated an ethos approximating that of heroic Modernists, the abstract art of the early twentieth century, in so far as they suggested that the boundless diversity of the universe was governed by iterative mathematical formulae. This idea has its followers today, notably artist and designer John Maeda, professor of media arts and sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Working with basic mathematical models, he has stripped computer-based art and design of its exasperating complexity, while producing gracefully intricate pattern-based abstractions.

Maeda’s courageous quest to equip artists with the optical knowledge of scientists (and vice versa) has a chequered history. Reacting against the flatness of Modernist painting, artist Margaret Benyon began laboratory experiments with the holographic process in 1968, producing dynamic works that created the illusion of movement and space without reintroducing perspective. She quickly established a poetics for holography, fabricating time reversed images and double exposures that exploited the medium’s unique illusionary qualities. Other artists dabbled with the process. Bruce Nauman constructed self-portraits such as Making Faces 1968 as extensions of his performance art. Dalí produced Holos! Holos! Velázquez! Gabor! 1972, a surreal homage both to his idol Velázquez and to Denis Gabor, inventor of the holograph. Despite such endorsements and the vast advances in technology since the 1970s, holography was never embraced by artists as photography was. Perceived as a novelty, its kitsch value undoubtedly played its part in Malcolm Morley’s recent series of holographic images of pirate ships sunken in beds of coral.

Abortive collaborations between scientists and artists were also vital to the development of computer-generated Magic Eye images. An electronic update of a 1950s depth perception test, Magic Eye allowed viewers to see full-colour three-dimensional models within two-dimensional patterns. The images were marketed widely in a series of books and advertisements in the 1990s, and were immensely popular both as a form of meditative entertainment and as an exercise for maintaining healthy binocular vision. Magic Eye artists worked with programmers to produce easily recognisable stereographs, such as dinosaurs golfing with dolphins on Saturn, all aimed at mass cultural production. Like holography, it is perceived to be expensive kitsch, the result of an inflexible process that has its visual limitations.

Notwithstanding the caveats, Rory MacBeth has produced his own Magic Eye Paintings 2002, visual orgies of Willem de Kooning’s Excavation 1950 and the cat illustrations of Victorian psychotic Louis Wain. When the electronic Pantone colours are hand-painted, the convex figurative illusion fails to materialise, leaving only camouflage. MacBeth keeps up the pretence that something can be seen by placing a motor behind his stretchers to dupe the audience into straining their eyes. Visually, his impressive paintings show us that such psychedelic imagery has much in common with the aspirations of Modernist abstraction. At the same time they deny us any deeper meaning, mocking the psychedelic desire to eliminate superficiality and gain greater ‘depth’. As much as our eyes might search, there is no figure behind the mask; there is nothing but the show. MacBeth’s Luddite antics, like those of many of his peers, point out that imaginative optical effects don’t necessarily require laboratory experimentation or a major research budget. Illusionism in contemporary art stems more from a desire simultaneously to mesmerise the audience while revealing the tricks of the trade, allowing the lure of mystification to pull away the magic carpet. Exploiting our desire to stand on both sides of the looking glass, such artists know how to use their illusions.