Glenn O’Brien’s Light Show Flashback

The Ambassador Theatre in Washington DC was a Baroque cinema palace from the silent days that was pressed into service for the psychedelic circuit in the late 1960s. San Francisco had the Fillmore Auditorium and the Avalon Ballroom, New York had the Fillmore East and Washington had the Ambassador, where every weekend you could see one of those strangely named bands that played psychedelic music. I remember I showed up there a week early to see Canned Heat. When you’re on psychedelics time sometimes plays tricks on you. Instead, the Strawberry Alarm Clock was playing. This was not cool. This was more uncool than going to see the Electric Prunes or Ultimate Spinach. But I decided to stay anyway.

The Ambassador itself was a cool place, where a person stoned enough to see Canned Heat could be entertained by the angels carved on the walls or the state-of-the-art psychedelic light show, which was the same sort of thing that was going on at the Fillmores. Dyes and coloured oils were swished in water and shown on overhead projectors, the kind of machines we studied maps on in school. This was mixed in with coloured gels, slides of mushroom clouds or American Indians, snatches of film – maybe a Three Stooges scene here and a train speeding into a tunnel there – and other lighting effects such as the strobe, which was usually switched on during a drum solo, highlighting the freak dancing of the more stoked audience members. But it’s the pulsing blobs I remember, like chromosomes imploding in time with the band, a hopped-up visual artist doing action painting in real time on the canvas of our minds. As I drifted away from the stage, the band, dressed like warlocks in a Russ Meyer film, played their cheesy repertoire of acid-tinged muzak: Incense and Peppermints, Rainy Day Mushroom Pillow, Barefoot in Baltimore, Sit With the Guru…

I wandered around the room where black lights were strategically positioned so you could delight in your radiant teeth, and I discovered a strange machine with a viewing port that fit close around the eyes, like an old one-person movie viewer. It had a button on it that said “Zap”. I put my face to the opening and pressed the button and got zapped. Literally. The word ZAP was imprinted on my retina by a flashed light. Delight turned to fear quickly. Okay, enough of the joke. Will it ever go away?

It went away. And so did the Strawberry Alarm Clock, and the Ambassador was demolished, but the light shows remain, deeply rooted in the acid flashback archives of my brain. Those pulsing blobs! They once had meaning.

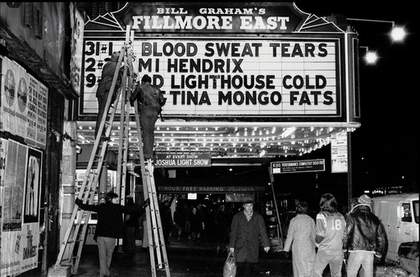

Amalie R. Rothschild

Changing the Fillmore East signs at the end of the Blood, Sweat and Tears show 28 December 1969

© Amalie R. Rothschild

Mary Woronov on dancing at The Dom

Gerard Malanga and I started dancing for The Velvet Underground at The Dom in New York in 1966. It was very new for a rock and roll band to have a show, much less a Warhol movie playing behind it. In art, however, it was the time of happenings and guerrilla theatre. When we performed in Philadelphia with Robert Rauschenberg, he roller-skated around a room, in and out of a movie screen.

At The Dom, Gerard was the one who chose the paraphernalia and tone for our dance. We did stuff like miming shooting up heroin with gigantic plastic needles. He got the strobe lights and gave me the costume, bought me my whip and my first pair of leather pants… you know, just your basic S&M stuff. We always wore leather boots and carried whips. We never rehearsed. It was complete guerrilla theatre. We performed wherever the Velvets played. Being a veteran of John Vaccaro’s Theatre of The Ridiculous, I knew what to do. It was natural to see it as a kind of transgressive theatre.

In The Dom we were on a stage in front of the Velvets, so the audience had to watch us. The band was also dressed in black. Everyone looked the same. You could tell the Warhol people; they all dressed in black, wore huge black sunglasses. They were called the “mole people” because they came out with these big glasses only at night. We all had the same boots, except for Nico, who dressed in white. She was interested only in singing, not in performing. The band never danced. They only stood and played; they looked at each other or turned their backs to the audience. Sometimes they would stumble because they were really high, and sometimes they would just walk away and leave their instruments on. It was part of the mystique of it. Everyone was high, though Gerard and I weren’t as high as the Velvets.

It was the time of hippies and communes. The Dom became an organic thing. It had a certain mystique. People moved rather than watched. There were films going on all over the walls, and there was this light show. It was a new kind of dancing – about being so high that people thought: I don’t even need a partner, I’m just gonna twirl until I drop. The audience became a part of the music by dancing. There wasn’t anything like that before – all you could do was go to a cocktail bar that had a little piece of floor for the mambo or the twist.

Warhol loved The Dom. He would stand up on the balcony and watch people, but he never danced. But even if you didn’t dance, you felt like you were, as the whole place was vibrating.

People on the West Coast hated The Velvet Underground. They thought we were odd, weird, dark and evil. There was a big dichotomy: they took acid and were going towards enlightenment; we took amphetamines and were going towards death. They wore colours, we wore black; they were barefoot, we wore boots. All they ever said was “wow” and we talked too much. It was the old NY is smart and LA is stupid routine.

The Dom’s dark communion went on for months in one form or another until Warhol and Lou Reed split. I got a job at Lincoln Centre to do “real” theatre, a pale comparison with Vaccaro’s. Then I moved to Los Angeles to be in the movies.

Mary Woronov talked to Mark Francis.

Ronald Nameth

Ingrid Superstar and Gerard Malanga perform with the Velvet Underground

Film still

© 1966–2005 Ronald Nameth, all rights reserved

Billy Name on Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable

The development of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable came when Edie Sedgwick left us to work with Bob Dylan, after an argument she’d had with Warhol. We were scheduled to do a Sedgwick retrospective film festival at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque, and when she walked out we decided to put on a more experimental event instead. Andy had been presenting a week of mixed media performances called Andy Warhol Uptight at the Cinematheque on West 41st Street in early 1966. We at the Factory had just hooked up with The Velvet Underground and were filming them. We screened the film of them playing on top of them as they performed. We then rented a space called The Dom, which was like a ballroom with an elevated stage. Here, we included the Velvets film, though this time we used a lot more of the Warhol films, for instance some of the screen-tests and the Kiss ones, over the band performing with Gerard Malanga and Mary Woronov dancing on stage simultaneously, plus all kinds of light effects.

Ronald Nameth

Gerard Malanga dancing at Andy Warhol’s Expoding Plastic Inevitable

Film still

© 1966–2005 Ronald Nameth, all rights reserved

I was taking photographs of almost everything that was going on, but I was also running some of the lighting systems and Andy, Malanga, Steven Shore, Paul Morissey, Danny Williams and me all switched around. We had spotlights with colour wheels and slides that we would project on the walls. We also used those gels – like a lava lamp – that you could squash to make shapes. John Cage had his multimedia things going on, but this was one of the first to be happening in dance spaces and to be advertised to a wider public. It was initiating that sort of event where you could just groove with the music and dance in a big space. It brought in a different audience. There were kids in their teens, and the hip people in their twenties and thirties.

It only went on for a month. Then the Electric Circus opened at The Dom, which was a more commercial version of EPI. So the moment was over pretty quickly. We were like the “grass roots” record that got covered by the top label.

Billy Name talked to Mark Francis.

Mark Boyle and Joan Hills’s magical projections

We met in 1957, and although we agreed that it wasn’t love at first sight, we decided we were going to work together for the rest of our lives trying to make art that would not exclude anything as a potential subject. We were influenced by the poets Rimbaud, Mallarmé and Baudelaire, wanting to work with everything and trying to figure out how we could even begin to attempt such a project. One strand of a solution began with us making mixed media assemblages and developed into our random studies of the surface of the earth. Another approach was through our events and projection pieces. We wanted to develop new ways of seeing and presenting reality.

We began experimenting with projections – with oils, dyes and things like washing-up liquid and a projector on the kitchen table – in 1962. It became a way of studying chemical and organic change. Joan and I, Joan’s first son Cameron and later our two young children, Sebastian and Georgia, would all take turns mixing chemicals and projecting the results on to the wall. You’d be looking at these things, and sometimes you’d see a reaction or an image that you thought no one had ever seen before.

Our first public performance of projections was during an event called Suddenly Last Supper in 1964. It marked the eviction from our flat. The landlord hated us working there and hated our pictures, but we invited about 60 people who had been to our place and knew what it meant to us, both as a home and a studio. The event had many elements on the themes of destruction and creation, birth and death, including projections of random films and slides which were burned on screen. One showed Botticelli’s Birth of Venus being projected on to the body of a woman. The slide burned in the projector and through the disintegrating image of Venus emerged the real woman. After the performance the audience emerged into an empty flat: we had all gone during the show, taking the furniture, the lightbulbs, everything.

We continued to develop our projections at the old ICA, collaborating with experimental composers such as Cornelius Cardew. John “Hoppy” Hopkins saw one of these concerts and asked us to do a show at a new club he was organising in Tottenham Court Road, called UFO. By this time the burning slides and exploding liquids had crystallised into an event called Son et Lumiére for Earth, Air, Fire and Water, which we did at the club. Afterwards, Hoppy came up and offered us ten quid to do lights for the rest of the night and then each week – an offer we could not refuse. One of the bands on that night, Soft Machine, came up after their set and asked if we would work with them on a regular basis. We liked their music very much: they were by far the best and most exciting band around, combining experimental music with rock, jazz and pop. They were ahead of their time. It was acetylene music. I think it was that same night that this young guy with a guitar jumped up on stage and jammed with them. We thought it was a bit of a cheek, asked someone who it was and they said: “His name is Jimi Hendrix.”

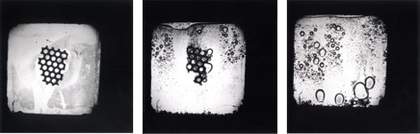

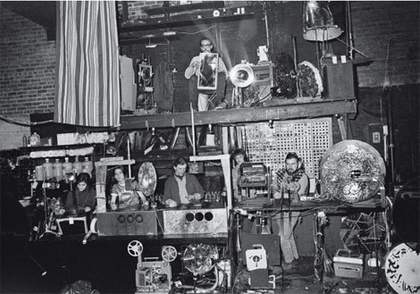

UFO was quite big, but dark and dingy, apart from the light from our projections. We were on a tower at the back – a bit of scaffolding with planks across it. We had four projectors and would try to get different reactions going in each one, mixing them with coloured filters. There was a lot of chance as the images were based on the chemical reactions that happened in the slides. Some created amazing effects. When we put acid on to perforated zinc it would immediately attack the zinc and there was a ferocious action: pieces of zinc would fly off the screen with bubbles exploding. You would put it on when Mike Ratledge, the keyboard player, was going mad on the organ, or Robert Wyatt was doing one of his amazing drum solos. It was very fast-moving work. When you saw that one of the chemicals was reaching the end of its cycle, you had to fade that out and bring in something else. It was not synchronised with the music, though your brain forced the two things together, making you think it was, which created something totally magical.

Mark Boyle and Joan Hills

Zinc being destroyed by acid in Son et Lumière for Earth, Air, Fire and Water 1966

At the time my brother was in a mental hospital in Glasgow, but he got himself down to London and came to stay with us. We took him to UFO, partly thinking it might help him in some way. There were hundreds of people there and he soon disappeared into the crowd, and we didn’t see him for two days. We later learned that he met a girl who turned out to be a psychiatrist. He told us how he’d had a dream “about a place with pictures going all the way around the room. Not pictures like you make, but pictures of moving colour, swirling and swimming, red, purple, green, orange. You would have loved it, it was kind of magical”.

After several months we were asked to go on tour with Soft Machine and Hendrix around the States. We liked the members of the tour immensely, but the conditions were appalling. You would wake up in Chicago, do a gig that night in Tucson and the next night you would be in another city 1,000 miles away. We’d have to go out and buy half a dozen bed sheets and sew them together to make the screen, or else they’d say, “oh no, you don’t need to worry about that, we’ll close the curtains and you can project on them”, and the curtains would be grey velvet. The tour took a lot of the magic out of it for us. We were knackered, we missed our kids and we wanted to get on with our pictures and other elements of our work. We had the first big exhibition of our earth pieces at the ICA the next year. Recently, we have become good friends with a guy called Neil Rice. He told us that he saw us and Soft Machine as a teenager and got interested in light shows. He borrowed his parents’ projector and started experimenting, and still does all sorts of fantastic lighting for bands and clubs around the world. Last Christmas he rushed out to his car and brought out a box. It was a liquid crystal projector. He said: “This is for you, for giving me a moment that changed my life.”

Robert Wyatt on Mark Boyle

Back in 1966 Soft Machine played at UFO on Tottenham Court Road. Mark Boyle did all our light shows at the club. What he was doing was industrial and dangerous. He wore goggles and got burns on his cheeks. God knows what he was doing with the slides. If he thought a slide needed to be torched, he would torch it. You can imagine what health and safety inspectors would think about that today. While most of the light shows of that time used images from Laurel and Hardy and war films, Mark was different. If you saw bubbles, they were real bubbles; if you saw a bit of film on fire, it was on fire. It was all real stuff. He would project from a great height at the back of the club, so we saw him only as a rabbit sees a car’s headlights.

Subsequently, Mark came with us on the road for the 1968 US tour with Jimi Hendrix – who was polite, shy and often a bit nervous. The music scene was quite a different set-up in America – all wealthy entrepreneurs, with enormous cars, pretending to be students, wearing Bermuda shorts and dark glasses. There was never anything underground about the American underground that I could see. The similarity of the language was confusing, misleading. Everything was different. You’d get people working at the big clubs in the States who would resent the intrusion of someone else coming in and doing their light shows, but Mark would just get on with it, always be on the case. What he had in common with Hendrix is that he was like a grown-up among kids. It is always nice to have a couple of grown-ups around.

What I liked about him is that he was serious. He liked a laugh, but he would say: “I’m just searching for the truth.” That may sound a bit vague, but if you look at his work, he is looking for truth and for what is really there, for what really happens. In that sense he is an old-fashioned artist, and a great man.

Ronald Nameth on John Cage’s HPSCHD

Ronald Nameth

HPSCHD lightshow environment 1969

© 1966–2005 Ronald Nameth, all rights reserved

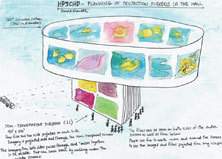

In 1967 John Cage began a two-year artist-in-residence programme at the University of Illinois. He got involved in many collaborative projects, the most ambitious of which was an enormous theatre piece of music linking chance and computer technology, involving seven harpsichords and a 52-channel tape orchestra. It was called HPSCHD – a computer abbreviation for harpsichord – and was held on 16 May 1969 in the assembly hall near the campus. The interior was shaped like an old Roman amphitheatre and could seat 16,000 people. It had large bay windows facing out on to the prairie and looked like a space ship from a distance.

Cage asked me to provide the lights and films for the event, so we created a huge circular screen, 340 feet in diameter, which was placed in the middle of the space, and projected thousands of hand-painted images and photographs. Under this hung another eleven screens. These were made of semi-transparent material so that imagery could pass through from one to the next. We used more than 6,400 individual slides from various sources, including NASA, Mount Wilson Observatory and the Adler Planetarium, plus 1,600 hand-painted ones. It was a bit of a rush to finish these in the days running up to the event, but everyone joined in, including Merce Cunningham, who had just arrived from New York. We also utilised film footage of outer space, including Georges Méliés’s A Trip to the Moon (1902), and Stonehenge and other ancient sites from around the world, as well as some of John Whitney’s computer graphic films.

Rather than have people sitting on the seats around the edge, Cage put the audience in the middle with the music and imagery, so everyone could walk around and through everything. It felt like being at a carnival. It was a very total experience – an immersive space of sound, movement and images. Ronald Nameth has been collaborating with fellow artists and friends since the 1960s in the making of films. He currently works in digital video – recording, documenting and experiencing art in life.

Ronald Nameth

Sketch for the lightshow and film projections for HPSCHD 1969

© 1966–2005 Ronald Nameth, all rights reserved

Joshua White on the Joshua Light Show at the Fillmore East, New York

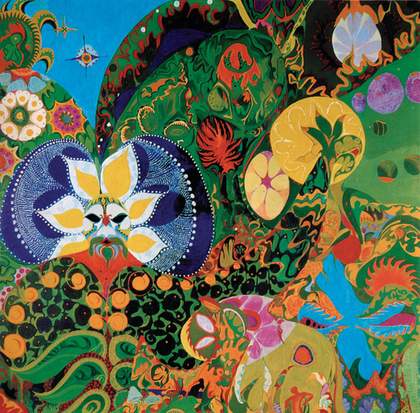

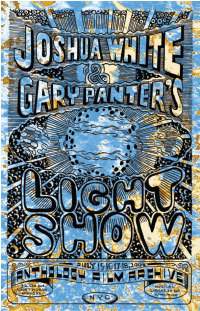

Gary Panter

Poster for the Joshua White/Gary Panter lightshow performance 15–18 July 2004

© Anthology Film Archives

I was a teenager in the 1950s in New York when my parents bought me a student membership to the Museum of Modern Art. It was on my way home so I stopped in often. I particularly enjoyed looking at a piece by the pioneering light artist Thomas Wilfred in the corner of a dark room. His was the first work I ever remember that dealt with light as a pure form. It was projected from behind on a small screen, and I would sit and stare at it. I liked to bring my girlfriends there.

After studying theatrical lighting and filmmaking in university, I returned to New York. I got involved with an artist named Bob Goldstein, who liked to stage all-night parties called Lightworks in his loft, where people danced, mirror balls spun and multiple screens showed slides and films in support of the music. After apprenticing with Bob, I struck out on my own. The first discotheque movement had come to the city. Every nightclub was putting in a dance floor and playing records. My first work was building control panels and flashy lights. Unlike my competitors, I didn’t try to invent anything spectacular; I simply adapted existing equipment and gave it a cool name.

In the summer of 1967, The O’Keefe Centre in Toronto made a deal with the well-known promoter Bill Graham to bring the “summer of love, San Francisco experience” to Canada. Bill brought Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead and a light show called Headlights. My company was hired to produce the support services and solve problems. We created a giant rear projection screen behind the band. This week was an epiphany for me.

With my colleagues, I built my own show and started looking for bookings. It didn’t take long. Graham opened the Fillmore East on 8 March 1968. He was a brilliant showman and felt the light show was important. He booked the best acts, Jimi Hendrix, The Mothers of Invention, Janis Joplin, The Doors and The Who. The light show was almost completely abstract. We used different techniques. One was projection of oil and water, which became a very flexible palette. Carefully colouring both materials made this effect stunning, and an overhead projector allowed us to make the mixes horizontally. We had several projectors and artists running them, and also used many slide projectors with hand-painted slides. Large multicoloured plastic discs called colour wheels would turn in front of several projectors at once, causing the colours to shift constantly. I also had several hundred specific images that could be dropped into the abstract soup – such as a peace symbol. It was our homage to Thomas Wilfred.

Amalie R. Rothschild

The Joshua Light Show team at Fillmore East. Left to right: Jane Rixmann, Cecily Hoyt, Bill Schwarzbach, Joshua White, Ken Richman. Above: Thomas Shoesmith

Photo: Amalie R. Rothschild © Amalie R. Rothschild

Sometimes the music would go on and on and on. During Grateful Dead concerts, late in the show we projected a pure white circle. It was just light with nothing in it that came up very slowly. People swear they saw God in this circle.

We came from a practical, academy-trained world. When we had an idea, we got it done. For me that was really the magic, and it stayed relevant as long as the Fillmore East was relevant. All that changed after Woodstock in 1969. I stood on that stage with my light show. The screen was now 80ft wide. With an audience of 400,000, we were irrelevant. Six months later, I quit. I never stopped making art though. For example, I recently collaborated with the artist Gary Panter.

Amalie R. Rothschild on the Fillmore East

I started going to the Fillmore East in 1968, as I was studying film and television at New York University’s graduate School of the Arts, which was literally next door. The film equipment technician at NYU was one of the first sound engineers at the venue when it opened, and he got me a pass. I didn’t know most of the music at that point, but I fell madly in love with the whole environment, particularly the staging and production of the Joshua Light Show. I decided that I wanted a job there, so I put together a pitch and called up Josh White, who hired me on the spot for $50 a week. I provided them with graphics material, slides and film footage, including general stuff, both abstract and not, hand-made film loops, animation and hand-drawn scratch loops. This material became part of the repertoire that the light show could use for a variety of bands.

I shot footage of all kinds of things and incorporated ideas from many sources. For example, for the Grateful Dead’s trademark song Casey Jones, which they often used to open their set, I filmed a steam locomotive that used to run from Hoboken to upstate New York. I employed a zoom so that the huge old engine, belching smoke, slowly came right up into the frame, rounded the curve and then went whooshing by as I drew the lens back. The Dead were almost a house band at the Fillmore East – they played there 27 times and their performance and personal style gave those of us working the light show tremendous scope for inventive presentation.

The response to the light shows from the bands was varied. While [the Dead’s] Jerry Garcia would frequently have his back turned to the audience so he could look at the show, Crosby Stills and Nash stipulated in their contract that they didn’t want one at all.

I was providing software imagery rather than performing the light show, which meant I had time to take lots of photographs. I shot the back-stage action because I recognised what an extraordinary creative environment that place was. I was a bit shy, like a fly on the wall. My cameras were my protection and I was certainly aware of what a chauvinistic period of history that was. I had to be careful to be taken seriously, as I was not looking for a boyfriend or a one-night stand. I was most at ease with the technical staff of the theatre and was incredibly lucky to have been a part of it all.

For some bands the Fillmore East was their first major US venue. We could listen to the music in advance of their records and think up what kind of specific imagery we would use. The Who’s Tommy presented a real opportunity to develop something more theatrical, more spectacular, since there was a libretto to work with. Bill Graham, who owned and managed both Fillmores, always understood the importance of giving the audience a good show and gave us the extra money for a Tommy production budget. I got $500 to come up with special film effects, which included a sequence for Acid Queen. I used Cecily Hoyt of the light show as my actress and filmed her nude, in black and white, walking back and forth across the stage. I shot the same scene over and over with a variety of lenses, camera angles and speeds, including slow motion. I edited these into multiple rolls which were then printed down on to one strip of 16 mm film in four colours. Although no one is disputing how fabulously The Who played, some observers felt that the light show added such a good visual component that the six nights of Tommy at the Fillmore East in October 1969 were the definitive performances.