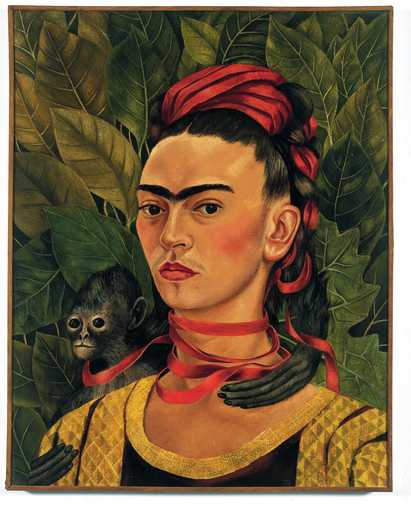

When we think of Latin American art, we often think of the exotic magic realism of Frida Kahlo or the grand revolutionary narratives of the Mexican muralists. The recent “rediscovery” of Latin American conceptual art from the 1960s and 1970s has done much to change these stereotypes, but even this has tended to be defined within a nationalistic context – not least by certain of the continent’s critics and curators eager to showcase the art of their countries. In the process, what has been ignored is how these artists – be they Brazilian, Mexican, Argentinean, or Venezuelan – not only travelled to, lived and exhibited in and absorbed the culture of New York, Paris or London, but also contributed original conceptual practices which can be fruitfully compared with the developments in European and North American art at the time.

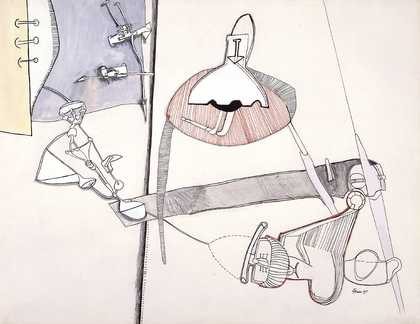

The 1960s was a period when all established values were scrutinised. The traditional status of the artist, the commercial value of the art object, the distribution of art and its public were key issues for American, European and Latin American artists alike. They began to use new materials, such as everyday objects, and had new ways of presentation – a set of photographs presenting research or documenting a performance, for example. For the Latin Americans, the audience was a crucial aspect of their work. Undoubtedly, they had fewer galleries, dealers and collectors, and the gap between a small art-appreciating bourgeoisie and the great majority of an often less literate population was acutely felt by many. This may explain why Brazilian artists, for example, pioneered the creation of works that the viewer could touch – whether boxes to be opened, objects that can be worn, or group performances. One example is Hélio Oiticica’s Glass Bolide 14 (TO BE I) 1965–6, where viewers could plunge their hands into a transparent container filled with a mass of shells and sift them through their fingers. It was primarily a tactile experience. In contrast, the message from the American Robert Smithson’s Mirror with Crushed Shells (Sanibel Island) 1969, in which a pile of shells is placed on three mirrors in the corner of a room, was: look but do not touch. Similarly, while Lygia Clark’s series of sensory objects, such as Sensory Masks 1967 or Sensory Gloves 1968, and Eva Hesse’s Untitled or Not Yet 1966, made from dyed fishnet bags, paper and metal weights, share a vocabulary of soft, organic shapes and materials, the spectator can touch or wear Clark’s, but only imagine the tactile sensations of Hesse’s work. In the late 1970s Clark would use some of these objects – plastic bags, stones, nylon nets and rubber tubes – as therapeutic tools for curing mentally ill patients; she sought to help them to structure their sense of self by appealing to the unconscious memories stored in their bodies.

Of course, Latin American artists did not have a monopoly on interactivity. Dan Graham’s Present-Continous-Past 1975 consists of a room with mirrors, a camera and a television screen. When viewers enter, they see themselves in the mirrors and notice the screen; eight seconds later they realise that their actions have been recorded and are being played on the TV, prompting them to experiment with various poses so they can watch them being fed back through video. Like Oiticica and Clark, Graham produced a work that can exist only when participants interact with the provided object – as Clark put it, the artist becomes a “proposer” rather than the creator of a finished piece. Unlike the Brazilians, however, Graham privileges the visual over the sensual, reflecting the impact of technology on our behaviour and showing the body mediated by the disembodying lens of the camera.

It seemed that many of the most established American conceptual artists were focused on self-reflexive investigations of the artistic process and the definition of art. John Baldessari, for example, asked various painters each to copy a photograph of his friend’s hand pointing to an object, and inscribed each canvas with the caption “a painting by”, followed by the name of the commissioned artist (Commissioned Paintings 1969). Who is the author of these works: the painters who transferred the image on to the canvas, Baldessari’s friend who chose the “subject matter” by pointing his finger at everyday objects that attracted his attention, or Baldessari who came up with the idea of the piece? The Brazilian Cildo Meireles also drew on language to question traditional notions of authorship. In 1970 he inscribed the words “yankees go home!” on to empty Coca-Cola bottles that would be returned and re-circulated by the company. The piece, Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project, or “mobile graffiti” as he called them, served as anonymous, undercover propaganda against what he saw as American imperialism in Brazil and the rest of Latin America. Renouncing authorship went hand in hand with political activism aimed at raising people’s awareness of the “ideological circuits” which surround them.

It is hardly surprising that Latin American artists were more often engaged with their social and political contexts: at the time, many Latin American countries were in the midst of violent upheaval, including a repressive dictatorship in Brazil. Not everyone, however, believed that North and South American artists existed in parallel cultural spheres. In his introduction to the 1970 exhibition Information at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curator Kynaston McShine explained: “If you are an artist in Brazil, you know of at least one friend who is being tortured; if you are one in Argentina, you probably have had a neighbour who has been in jail for having long hair… and if you are living in the United States, you may fear that you will be shot at, either in the universities, in your bed, or more formally in Indochina.” Demonstrating the increased politicisation of the art world in the face of the Vietnam war and mass protests at home, McShine sought to counter the idea that all conceptual art was isolated from its context, and emphasised the prevalence of violence and repression for artists in both continents. He had travelled to Latin America to prepare the exhibition, and selected Cildo Meireles’s Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project for the show, among other works.

McShine was not alone in believing conceptual art to be an intercontinental phenomenon. In her landmark 1973 survey of this period, American critic and curator Lucy Lippard included Latin American artists such as the Argentinean Grupo de Artistas de Vanguardia (Group of Avant-Garde Artists). In order to counter the government’s media propaganda about one of the country’s poorest provinces, Tucumán, the group had decided in 1968 to distribute posters and flyers in the city and mount an exhibition documenting the economic disaster caused by the closing down of sugar refineries and exposing the state’s sham development plan. The idea that providing information in itself could be political was shared by the German-born artist Hans Haacke, who was also included in Information. In 1971 he researched the real estate holdings of the Shapolsky family in Manhattan, and displayed the results - Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971 1971 – in his exhibition at the Guggenheim. The harmless-looking maps and photographs of building façades, accompanied by typewritten descriptions of ownership and prices, added up to a biting indictment against the monopoly of one elite of wealthy proprietors over the slums of the area.

Another model for political activism explored by artists on both continents focused on the street, rather than the gallery. To confront passers-by directly, the black American Adrian Piper decided in 1970 to stage performances such as going shopping wearing a shirt painted with white paint and bearing a sign saying “Wet Paint” in huge capital letters, or riding the subway with a towel stuffed in her cheeks. Piper’s conception of the artist as a “catalytic agent inducing change in the viewer” was shared by the Argentinean Victor Grippo, whose Construction of a Traditional Rural Oven for Making Bread 1972 in a square in Buenos Aires aimed to remind passers-by of the lost rural community ritual of collective baking and sharing bread. Spontaneous gatherings were deemed subversive, and the police promptly came and smashed the clay and brick oven. A year before, the Guggenheim Museum had closed down Haacke’s retrospective on the basis that his Shapolsky piece was not art: a more covert type of censorship, certainly, but proof of the disturbing nature of this work none the less.

The differences, and similarities, between South and North American art in the 1960s and 1970s demonstrate the variety of forms that conceptual art could take across the international board. Trying to specify what is typically Latin American about the work of artists such as Meireles, Oiticica, Clark, Grippo or the Grupo de Artistas de Vanguardia is even more elusive than defining the shared characteristics of American conceptual artists, who at least could claim common artistic influences as well as a more unified socio-economic context. For one of the most relevant lessons of the 1960s and 1970s is that local and global events are, more often than not, intrinsically linked.