“When I drive across this country, with autumn falling and rustling to pieces,” wrote D.H. Lawrence in a letter of 1915, “I am so sad, for my country, for this great wave of civilisation, 2,000 years, which is now collapsing, that it is hard to live. So much beauty and pathos of old things passing away and no new things coming.” You recognise the sentiment, of course. There goes the splendour that once was England, and not for the first or last time. Nineteenth-century English literature, particularly the work of the Romantic poets, had dwelt at length on the fading of rural communities, and after the early-modernist interregnum in which Lawrence and others gave nostalgia a mythological spin, the refrain was heard in social commentary. Equal parts melancholy and anger, it filters through J.B. Priestley’s English Journey (1934) as the author pinwheels across a landscape scarred by the operations of industry and increasingly laced with cheap knock-offs of American culture, and persists from George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) to contemporary updates of the mourning-travelogue genre such as writer/photographer Nick Danziger’s A Journey to the Edge (1997). And, while not necessarily reaffirmed, it underpins an appreciable tranche of contemporary art made in this country, particularly those endeavours that call attention to elements of the English scene that are unseen - either because, for whatever reason, we don’t notice them anymore, or because they’re old things that have passed away.

Mike Marshall

Front Garden 2004

So let’s drop the ghost of J.B. Priestley into the double passenger seat beside Andrew Cross, as the latter films his non-chronological road movie 3 hours from here (2004) while sitting 8ft above the ground in a truck travelling – and approximately following the writer’s original route – from Southampton docks to the world’s first purpose-built industrial estate in Manchester. Whatever Priestley might think of Cross naming his ongoing series of films and photographs on the English landscape An English Journey, he would perhaps be superficially pleased by much of the vista scrolling past his window, once blackened by coal mining, now re-greened. (“We’re probably seeing the English landscape at its most picturesque since before the Industrial Revolution,” said Cross in a recent interview.) But industry hasn’t vanished, the artist tells the writer, it’s just incognito. The roads are full of trucks like this one, whose contents we don’t care to guess at, and there are factories aplenty; but, as Cross’s calm, hieratic, honest photographs demonstrate, they’re made to look like farms or absolutely neutral, modernist white blocks. For him this development reflects a class issue, representing the embodied wish of the middle classes to disengage from the nitty-gritty of production. Coming across like a frictionless computer simulation of the driving experience, what his work achieves is a state of suspension, a productive boredom wherein it is possible to stop and consider how social changes (such as globalisation) manifest themselves on the landscape; how the tended earth itself has been, since the advent of agriculture, constantly in a state of Heraclitean flux.

This can be hard to notice. The English landscape entrains a problem of vision: for long stretches it can seem virtually ambient, almost too familiar to apprehend, and the bits which aren’t natural can become invisible too. Do we see pylons, for example? We might notice when they’re gone, since they give scale and organisational structure to the view. Decontextualised and clustered together, as they are in Simon Periton’s recent paper cut-out (or “doily” as the artist prefers to call his signature works, the implication of domestic sweetness invariably playing against a less friendly element), Stairway to Heaven 2004, pylons are malevolent, domineering, Dalek-like things. To drive through our once-again-picturesque countryside and, thus cued, stubbornly focus attention on the web of electricity cables crackling above it is to banish any formlessly favourable feelings for the untainted great outdoors, to observe how this small country’s green space is necessarily bisected by industry and to isolate the convolutions of vision that allow us to forget it.

Mike Marshall

Gravel 2003

Off the motorway and away from the fields, as we hum towards the villages and suburbs where nature purportedly lies tamed, there are still unwieldy fluxes, subjects hiding in plain sight and an excess of meaning skulking in the bushes. An habitué of this maligned liminal zone, Mike Marshall chooses subjects that combine the natural and man-made and embody the sort of quotidian event we’d usually breeze past on our way to the church fête. Water sputtering comically from a pirouetting sprinkler on a summer’s day in the video Days Like These 2003, for example; or a light-splashed, almost liquid network of branching weeds dotted with tiny red and purple flowers. (The photograph that captures the latter, 2004’s Front Garden, comes as close as any picture in living memory to the beautifully attentive suburban mood of Stanley Spencer’s 1930s paintings of cottage gardens and allotments, which similarly found surprising weight in the lightest of gestures.) Abetted by his fascination with oblique textures - tarmac against shady foliage, light bouncing off gloss-painted walls – Marshall’s is often an art of evanescent composition and instantaneous memory, the tiny, right-looking equilibrium of elements that expires faster than a mayfly.

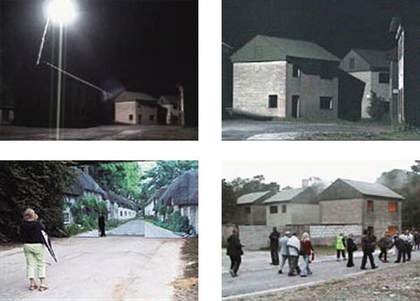

If Marshall’s camera delineates transience through modest epiphanies within a cultured landscape, a rather more tectonic shift within a local English environment was occasioned by Artangel’s Imber project in 2003 with the Georgian composer Giya Kancheli. The 160 inhabitants of this small village on Salisbury Plain were evacuated in 1943 when Imber was requisitioned for the training of US soldiers. Promises were broken, the place remained a firing range and civilians haven’t been allowed to live there again. During Artangel’s three-day event, the scarred concrete block houses that have mostly replaced the original dwellings were full of pumpkin-yellow light and Kancheli’s haunted music, the memorial culminating in a candlelit procession and live performance of specially written psalms and poetry. Interventions were otherwise fairly minimal, prompting the question of whether a village can temporarily become a readymade upraised on a cloud of context. As such, Imber would stand not only for similar cases of domiciliary denial, such as Tyneham (also “borrowed” during World War Two, this Dorset village has seen an afterlife as a film set), but for the whole disturbing idea of the unlimited scope of military expediency as it reshapes the landscape and, consequently, people’s lives.

Artangel

Imber project 2003

Film still

© Courtesy of BBC Wiltshire

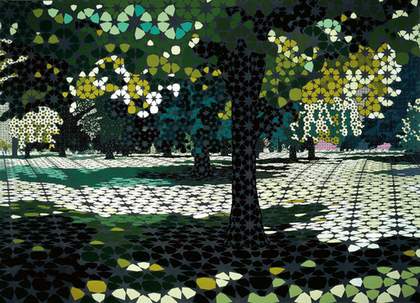

Not that it’s impossible to locate a sense of alienation in the most seemingly placid, Arcadian surroundings; particularly if one exploits the non-indexical, layering capacities of painting. Toby Ziegler’s canvas Arrows of Longing 2004 materialises a sun-dappled park as if it were a virtual reality environment, or reality seen through The Terminator’s artificial eyes: every tree, every leaf and every stretch of cambered parkland sports repeating designs that are variously trapezoid and star-shaped. His Comfort or Death 2004 is a hellish field of grey pointillist blobs, dotted with spindly red blossom trees so desiccated as to resemble showers of blood, and behind which a sun is setting. If these works’ chief iconographic reference is the cultivated parkland milieu that originated in England in the eighteenth century as a formalised mini-utopia in which nature was merely artistcorralled, Ziegler insinuates that such civic planning now represents not only an anachronism, but also a sort of prison: a pressure valve for stressed city-dwellers who can’t really “go back to nature” because they get agoraphobia when they lose mobile phone reception, and are thus left with a fatal yearning for an Edenic rural tranquillity that can’t be had anymore.

Toby Ziegler

Arrows of Longing 2004

© Toby Ziegler

The arcane genera that percolate through Clare Woods’s paintings, meanwhile, suggest that it never could. Typically, her skeins of gloss paint (suggestive of Pollock with a Homebase fetish) meld to suggest dense masses of foliage, and if their slick surfaces keep the viewer at arm’s length, the magmatic images that one spots among their negative spaces actively repel. Grinning skulls, rigormortised rabbits, tree spirits and ancient Green Man faces all go flickering by. In paintings such as the enveloping, multi-panel Failed Back 2004 it’s as if the natural world were channelling multiple pagan pasts, like the witnesses to 5,000 years of English bloodshed whose testimonies float up from one patch of Northampton earth in Alan Moore’s novel Voice of the Fire (1995). Woods’s work is not so much about an irrational past as a continually illogical present, strangely happy to be arrayed with hangovers from history and less advanced than it would like to think.

Embalmed here is something of the mythic “great civilisation” whose passing Lawrence lamented, its finer connection to the land and its freedom from pollution. The now, in whatever era, has long been convoluted and overlaid with multiple messy histories both true and legendary, tranquil and violent; pasts which the yielding repository that is landscape can be seen as constantly expanding to contain and bear witness to. What art can do, given this subject, is nudge us actively to look and scrupulously to remember without the cataracts of nostalgia. And, sometimes, to stop reminiscing for long enough that we fully inhabit those fleeting oases of calm in the present. At which point, it might be worth pulling Priestley out of that cab and back into the last century; I see a Little Chef coming up.