My younger brother Simon, who would’ve been about 12 at the time, helped Dad to make his soft sculptures on Mum’s old Jones sewing machine. They used lengths of raw canvas and sewed them into ‘sausages’ – that’s what we used to call them – before filling them with polystyrene balls. Dad then painted them with acrylic. My sister Kate, about eight years old back then, was too young to help, but remembers chasing the loose balls all around the house. The hardest bit was getting them into the tubes – they went everywhere!

The soft sculptures were created in Banbury, where we moved in the 1960s. Dad had two studios with big bay windows at the front of the house. I suppose that made it easier for my mum Kath to have a role in their making as well. Otherwise, she had six children to look after, and ‘the old man’ was teaching and painting and partying, or whatever, so it was pretty full on for her.

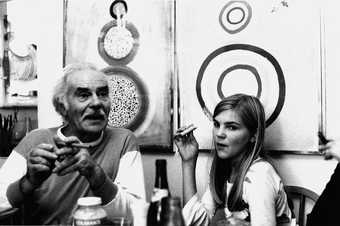

Terry Frost and his daughter Kate in the Banbury house, 1973, photographed by Roger Mayne

© Estate of Roger Mayne, courtesy Sansom & Co

They would’ve been the only art thing my mum was involved in. That and hoovering the backs of all of Dad’s canvases, because they always used to get filthy. During the installation of the Terry Frost centenary show at Leeds Art Gallery, the back of Yellow (Moonship) 1974 had to be hoovered by a conservator. I quickly phoned up when they asked permission, because I had memories of my mum actually cracking the acrylic on the other side of a couple of the canvases when she did it. It was a relief when I heard they weren’t going to use a Dyson.

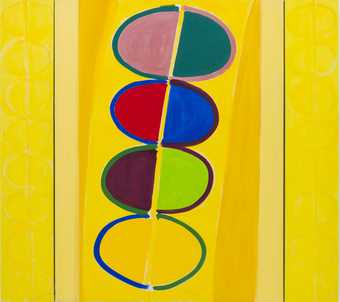

Terry Frost Yellow Moonship 1974 on display as part of the Terry Frost exhibition

© The estate of Sir Terry Frost. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2015

Dad called some of his soft sculptures Bundles of Sunsets, and I know exactly what he meant. Every morning, looking over towards Newlyn in Cornwall, he would watch the sun rise. For a long time, I would go and have a boiled egg for breakfast with him after dropping my wife Linda off at work, and the sun would be coming up. It was amazing. Pure colour. Now every evening, where we live, we can watch the sun go down, and we get the green flash [an optical phenomenon that sometimes occurs right after sunset]. Pure colour. And I know that’s what he wanted to achieve in his bundles.

Terry Frost’s soft sculptures in the garden of his Banbury home, c1970-72

© The estate of Sir Terry Frost

Another important thing for him was going to Cyprus. He would get so poetic there and it used to drive me mad sometimes. We’d be walking along and he’d say things like, ‘Look, we’re between the two gods’ because he could see the sun and the moon both up at the same time. It affected him so much. The sun and the moon, colour and crescents, never left him.

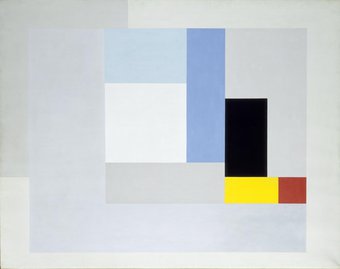

Back in the early 1950s, when Dad was in St Ives painting his breakthrough Walk Along the Quay series and works inspired by the arcing movement of boats’ hulls in the harbour, Ben Nicholson actually said to him, ‘You’ve got the shapes there that you’ll probably use for the rest of your life, Terry.’ And, of course, Nicholson was probably right because at the end of his career, in paintings like Green Below 2003, Dad had come back to the shapes he’d been using right when he started out. He developed these shapes into what he called Suspended Forms – an idea, like the sun and the moon, which never left him.

Sir Terry Frost

Green, Black and White Movement (1951)

Tate

Terry Frost

Green Below 2003

Estate of Terry Frost © The Estate of Sir Terry Frost. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2015

The hanging soft sculptures are a natural extension of this as in these he literally suspended forms in space. There had always been a construction element to Dad’s work, right back to the early 1950s when he was an assistant to Barbara Hepworth, and he had a real regard for the materials he was using. The textured brushstrokes you can see on the suspended canvases reflect the speed at which they were painted. They also bring out the fact that they were bent into arcs beforehand. The construction process – sewing, filling and hanging – corrugated the canvas and Dad knew that when he hit it at speed with the brush the acrylic paint wasn’t going to take to the surface fully.

He told me that what he was trying to do was to free colour from structure entirely, which he realised was almost impossible. I always remember him talking to me about wanting to create sprays of colour, or clouds of colour: pigment in the air. And now I know that if he had been able to have a team of people – proper assistants with expertise, not just a 12-year-old Simon – behind him, then he might have been able to pull that off. He would have been organising ‘colour happenings’…

When the family moved back to Cornwall the soft sculptures were consigned to the big garden shed where the lawnmower was kept, along with the garden furniture. I don’t think Dad knew at the time, but the shed developed a leak.

Terry Frost’s soft sculptures outside his house in Banbury, c1970-72

© The estate of Sir Terry Frost

In 2005, when my mum died, my sister Kate was clearing up the place and rang me to say they’d just opened up the shed and had found all of the ‘sausages’ in there, except they were rotten and the polystyrene had leaked out. She said: ‘What shall I do with them? We’ve got a big bonfire here…’

The small black-and-white ring is the only one that survived. I’ve got no idea why. Maybe because it’s the smallest one and so might have been hanging up in the shed. It’s a shame some of the bigger ones didn’t stay dry, but the old man had just thrown them in the bloody shed, all on the floor.

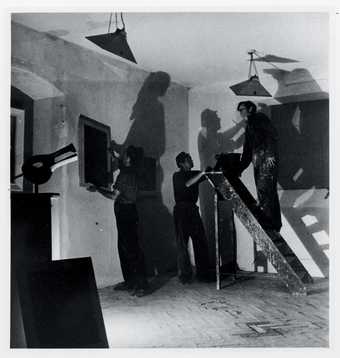

Installation view of the ‘Colour Play’ room at the exhibition Terry Frost, Leeds Art Gallery, 19 June – 30 August 2015

© The estate of Sir Terry Frost, photograph by Jerry Hardman-Jones, 2015

For the centenary exhibition, the curators at Tate St Ives took the surviving one as a model to have them all re-fabricated. When we saw the soft sculptures at the show opening in Leeds, we were relieved, because none of us had seen them before they were put up. They looked fantastic. Simon said he thought they looked even better than the originals – probably because we’d had professional help this time round!