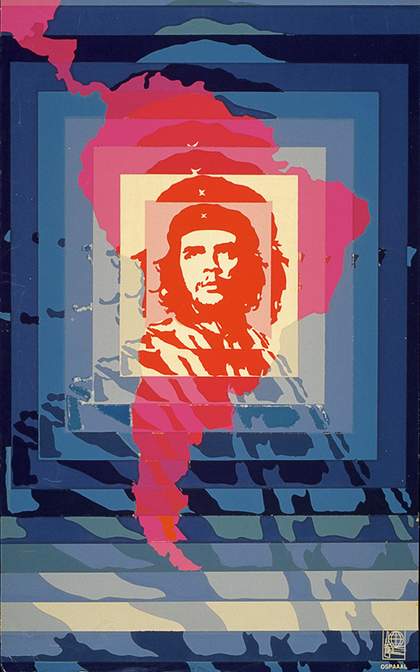

Elena Serrano

Day of the Heroic Guerrilla 1968

Poster, 545 x 340 mm

© Gift of OSPA A AL Museum of Modern Art, New York, courtesy Lincoln Cushing/Docs Populi

During the tumultuous days of June 1789, representatives of the French common people began to organise themselves into a National Assembly. Locked out of the traditional meeting hall, they were forced to convene on a tennis court, where they were reluctantly joined by members of the clergy and aristocracy. As the Baron de Gauville described it:

Those of us attached to their King and their Religion positioned ourselves to the right of the presiding member, in order to avoid the shouting and the indecent language coming from the other side… Several times I tried sitting in different parts of the room, in order to be more the master of my own opinion, but I absolutely could not sit on the left. If I sat there, I was the only [one] around who voted as I did and so was subjected to the mockery of the galleries.

Since the French Revolution, this spatial division between right and left has become the standard framework for conceptualising politics. Tate Liverpool’s Art Turning Left is an ambitious attempt to trace how the ideas and values of the Left have informed art-making since 1789. The French Revolution, with its overturning of the old static social hierarchies and the National Assembly’s ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen’, is often taken as the founding event of modernity. Our contemporary conception of art, with its emphasis on change, transformation and the new – all the qualities we associate with modernism – would clearly be unthinkable without it. But beyond a modernist desire to upend the status quo, what effect has leftist thought had on the way people make, distribute and consume art? New art is often described as revolutionary, but is that anything more than a metaphor?

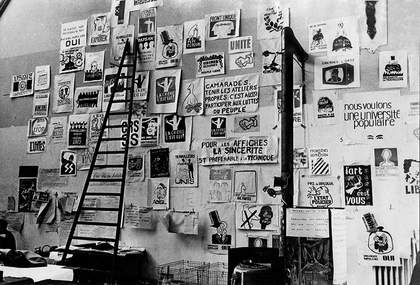

Photograph of the Atelier Populaire studio, 1968

Courtesy Philippe Vermès

The artist is usually seen as the individual par excellence – the person who expresses his or herself fully and lives by hawking the products of that self-expression to an elite audience of critics and collectors. The Left has always valued collectivity and community, and has sought to distribute art outside narrow commercial channels. During the Paris événements of 1968, the radicals of the occupied art school known as the Atelier Populaire submitted poster designs to a democratic vote, a ‘general assembly of control’ which checked them for uniformity of style, attempting to eliminate ‘bourgeois individualist creation’. Their preferred technique – screen-printing – erased the hand of the individual author, the combination of stencil and mechanical reproduction turning their unsigned works into expressions of their collective desire for change. Other forms of collective creation, from the surrealist group-drawing game of exquisite corpse to mass craft projects such as the AIDS Memorial Quilt, place the individual maker in a shared space, without denying his or her contribution. Sometimes the production of objects drops out altogether, and egalitarian social interaction is all that remains. Thus, Martha Rosler held a jumble sale in MoMA in 2012, while various experiments in ‘relational aesthetics’ have taken as their subject what the critic Nicolas Bourriaud has termed ‘the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space’.

![Guerrilla Girls [no title] 1985–90 Screenprint poster 430 x 560 mm](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/guerrilla_girls_no_title_two_bananas_0.width-420.jpg)

Guerrilla Girls

[no title] 1985–90

Screenprint on paper

430 x 560 mm

© Courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com

Another way of toppling the ‘bourgeois individualist’ artist, the petty dictator of creativity, is to incorporate chance processes, such as those explored by John Cage, or even to use hypnosis, like the Uruguayan Luis Camnitzer, to strip the artist of any possibility of self-defence. Since at least the 1960s, the notion that the structures of power are in some way embedded within the self has led artists of all kinds to seek to excavate them, to make them visible and be rid of them. The Situationist theory of the ‘Society of the Spectacle’ posits that the mass media have invested inanimate commodities with life and energy while sucking it out of the poor consumer, who can experience the world only by proxy, his desires having been routed through acts of purchase and consumption. Barbara Kruger’s ironic billboards (‘I shop therefore I am’), Victor Burgin’s détourned advertisements and even Banksy’s street art are just a few of many artistic deployments of Situationist ideas. The Brazilian conceptualist Cildo Meireles took Coca-Cola bottles, printed them with provocative ideological messages (‘Yankee go home’) and returned them to the shops to be sold, calling the project Insertions into Ideological Circuits.

Cildo Meireles Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project 7 x exhibition copies (detail) 1970

Photo: Tate Photography

The notion of equality, so central to the French Revolution, has been interpreted by artists as a call to break down various kinds of hierarchy. In the Socialist Realist art of the Eastern bloc, ordinary working people were given the heroic treatment previously reserved for aristocratic or religious subjects, but it was a style that quickly became kitsch and prescriptive, crowding out more avant-garde ideas of egalitarianism, such as Kazimir Malevich’s dream of Suprematism, a universal symbolic language that would be equally accessible to all. More recently, artists and curators have flattened the hierarchy between academic and outsider art, celebrating the untaught or unacknowledged creativity of those outside the institutional art world. Jeremy Deller and Alan Kane’s Folk Archive 2000–6 has collected together examples of British popular culture – everything from prison tattoo guns to carnival costumes and miners’ banners. Their fascination with popular festivities carries a faint echo of the work of Jacques-Louis David, a fervent revolutionary who authorised copies of his The Death of Marat 1793–4 to be used as a performance prop in Jacobin parades and organised a great festival of the people in 1791, designing uniforms, banners and triumphal arches. He also painted the National Assembly in their tennis court, the first visual representation of the right and left ‘wings’.

Jacques-Louis David

The Death of Marat (La Mort de Marat) 1793–4

Oil paint on canvas

1113 x 856 mm

Musée des Beaux-arts

© Musée des Beaux – Arts. Photo: C. Devieeschauwer

Artists have also considered equality in terms of the materials they use. Michelangelo Pistoletto, a driving force of the 1960s Italian arte povera movement, brought casts of classical statuary together with rags. Alighiero Boetti made a monumental tower out of corrugated cardboard. The use of humble materials mocked the expensive pretensions of marble and bronze. Painting and sculpture – the so-called fine arts – were for many years insulated by the ideology of ‘art for art’s sake’ from the everyday life of ordinary people. William Morris, a pioneering socialist, formed Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co to bring art to the masses in the form of stained glass, metalwork, wallpaper, fabric and carpets. Later, the Bauhaus school brought modernist values of rigour and utility to the manufacture of ordinary household objects. The collapse of the distinction between art and craft was, at its inception, a political gesture.

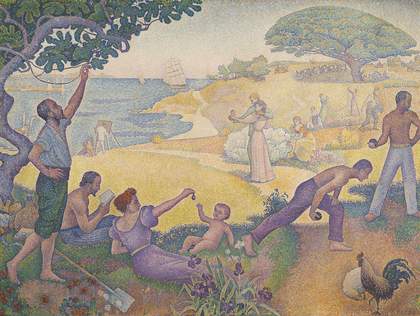

Above all, the art of the Left has always harnessed art-making to the project of imagining another system of social relations. Between 1893 and 1895 the pointillist painter Paul Signac, a committed anarchist, produced In the Time of Harmony: The Golden Age Is Not in the Past, it is in the Future, depicting people on an idyllic seashore, engaged in cultivating themselves and the land, painting, reading, playing games and sowing seed. Clearly referencing Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte 1884–6, it seems to underscore the constriction and boredom of the rituals of Seurat’s Parisian promenade. Signac’s men are shirtless, their trousers rolled up, his women dancing or lounging around with their children, quite unlike the self-conscious, ramrod-straight walkers in Seurat’s public park, their waists corseted, their collars tightly buttoned.

Paul Signac

In the Time of Harmony: The Golden Age is Not in the Past, it is in the Future (Au temps d'harmonie: l'âge d'or n'est pas dans le passé, il est dans l'avenir) 1894–5

Oil on canvas

300 x 400 cm

Ville de Montreuil

© Photo J.L. Tabuteau

From Le Corbusier to Archigram and Superstudio, architects have imagined (with various degrees of frivolousness) the physical environment of a future society. Artists have sought to populate such spaces with future humans, freed in various ways from the shackles of the present. Art as an act of resistance and an agent of change has manifested itself in diverse ways, from the wild imagination of the mid-twentieth-century avant-gardes to the nailed- down social research of Britain’s Artist Placement Group or, say, the Works Progress Administration in the USA.

With so much work of so many different kinds inspired by the Left, would a similar exhibition of the art of the Right be possible? There is plenty of art in the European tradition that celebrates, say, royalty, the church, or other forms of established power, from the mercantile elites of the Dutch golden age to English colonial adventurers, but when it comes to modern and contemporary art, there’s far less than one might imagine. It’s not so much that ideas of individualism, liberty or economic deregulation are incapable of inspiring creativity, but that we have an artistic culture which for the past 250 years has been predicated on change and innovation. If conservatism is an attachment to tradition and the status quo, then conservatism in art ends up as just a form of repetition of previous gestures, or worse (think of the trashy kitsch associated with Nazism and other authoritarian ideologies) a debased, servile classicism. With the notable exception of the futurists – a truly right-wing avant-garde – it’s hard to see what Tate would put in such an imaginary counter-exhibition.

In the meantime, the extraordinary fecundity of left-leaning art stands as testimony to a desire for social transformation that persists, even in an era when power is concentrated in the hands of a tiny global elite, whose influence on the art world itself one finds at every turn.