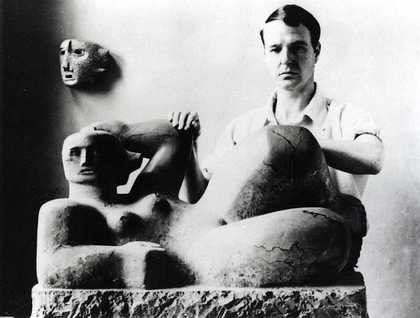

Henry Moore OM, CH

Recumbent Figure (1938)

Tate

Over my dead body will Henry Moore ever enter the Tate.

So, it is alleged, said James Bolivar Manson, Tate’s director between 1930 and 1938. However, just a year after his retirement, the new director John Rothenstein gladly accepted Moore’s Recumbent Figure 1938. The carving was the artist’s largest stone sculpture to date and has subsequently become one of Tate’s best known works.

The sculpture has had an eventful life. Stranded in New York at the outbreak of the Second World War, it found sanctuary at the Museum of Modern Art for the duration of the conflict. But it didn’t remain unscathed. In June 1944 two vandals broke into the MoMA sculpture garden and knocked Recumbent Figure off its plinth. In a letter to Rothenstein, MoMA director Alfred Barr downplayed the incident, stating: ‘Fortunately the damage to the sculpture was less than might have been expected. The only serious damage was that the head was knocked off.’

Henry Moore OM, CH

Upright Form: Knife Edge (1966)

Tate

Recumbent Figure and other well-known sculptures feature in a display charting Tate’s acquisition and promotion of Moore’s work, alongside lesser known pieces such as Upright Form: Knife-Edge 1966. Made in soft pink Rosa Aurora marble, this is the gallery’s only example of the artist’s post-war stone carving. For several years it sat on a table in his living room, but in 1970 he presented it to Tate in memory of his friend, the critic and scholar Herbert Read. His decision was prompted by the fact that when their friendship was closest – in the early 1930s – he had worked primarily in stone. Following Read’s death in 1968, Barbara Hepworth, Naum Gabo and Ben Nicholson also donated works in his memory.

Moore first proposed the idea of a major gift of his sculptures to Tate in September 1964 during an informal conversation with Rothenstein. Negotiations over the terms and what it would include took place over subsequent years, and even before any paperwork had been signed, news of the donation was announced in the press in February 1967. The proposal immediately divided opinion. One letter to The Times joked about the creation of ‘Moorehenge’, while others were anxious about Moore’s reported demand that his gift be exhibited in its entirety in perpetuity. One of the terms was that the works would remain in the artist’s possession for his lifetime, should he so choose. However, 36 bronze and plaster sculptures were delivered to Tate in 1978, and were shown that year as part of an exhibition celebrating Moore’s eightieth birthday. One of the pieces included in the gift was Animal Head 1956, which is on display at Tate Britain for the first time in 35 years.

Henry Moore OM, CH

Animal Head (1957, cast c.1957–62)

Tate

At the close of the birthday show in late August 1978, Tate’s then director Norman Reid reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end, ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’. Thirty-five years on, we are able to assess the legacies of Moore’s gift and his contribution to British art.