The late spring and high summer of 1972 saw the release of three records that defined a new era. The first was T Rex’s Metal Guru, number one for four weeks in May and June – the peak of their career both artistically and commercially. Late June heralded the top ten return of David Bowie, with Starman, the song and the Tops of the Pops performance that sealed his ascent to superstardom as an androgynous glitter-clad alien – the darling of the pretty things who would form the new pop generation.

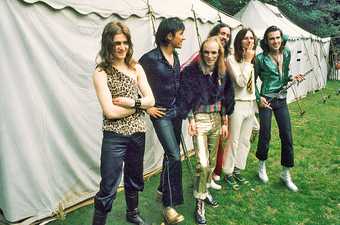

Late August witnessed yet another mutation. Roxy Music’s Virginia Plain is a barrage of witty images and allusions matched to a stomping, almost burlesque beat. The sound picture is complicated and dense: guitar, saxophone, piano and the strangeness of an EMS synthesiser, which takes the final instrumental solo – a sequence of oscillations and pulses that spiral off into the future. The single was a huge hit, reaching number four in the charts. If anyone was in any doubt that this was a takeover, all they had to do was watch the group’s Top of the Pops performance. Bright colours and lurex abound. There is guitarist Phil Manzanera in his fly-eye glasses. Drummer Paul Thompson, dressed in Tarzan leopardskin, wallops the kit, while synth player Brian Eno is barely seen – except for a close-up of his silver gloved hands in sync with his whooping solo.

Roxy Music's Paul Thompson, Bryan Ferry, Brian Eno and Phil Manzanera in 1972

To one side of a group who, in their clothes and posture, fuse the 1950s with a fantastical future, Bryan Ferry gives the perfect pose – a performance that in its stylised archness backs up the promise and threat of the lyrics. For Virginia Plain is a classic Trojan Horse, a three-minute pop song that is nothing less than a cultural manifesto as powerful and as condensed as Richard Hamilton’s 1956 Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? The record is a montage, an assemblage of allusions from fine art, celebrity culture (‘the Holzer mane’ referring to an early Andy Warhol superstar), advertising slogans, the Art Deco revival and several degrees of pop nostalgia – for instance, the 1971 film The Last Picture Show, which harked back to the small-town Texas of the early 1950s. Underlying this montage is the simple message: ‘Me and you, just we two, got to search for something new.’

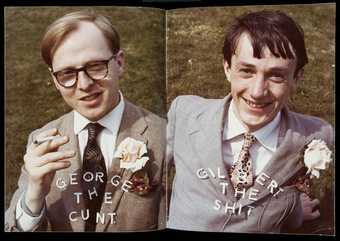

By the summer of 1972, the idea of glitter and glamour was well-established, having begun with such disparate sources as the trash chic of Warhol’s superstars and the fine art practice of Gilbert & George (their 1969 self-portraits), and having been taken up by Marc Bolan – thanks to his friend and colleague Chelita Secunda – for the full T Rexstasy phase that kicked off in earnest during 1971. Bowie had also experimented with it in the previous year in his appearance at the Roundhouse with the band The Hype. Music industry veterans since the mid-1960s, Bolan and Bowie had passed through a hippie phase before their reinvention as 1970s teen stars. Roxy Music arrived as though fully formed: there was no compromise in their approach, no past taint of patchouli or counter-cultural ideals. Ferry’s whole demeanour is affected yet completely integrated with his person and his persona. It’s totally authentic, but in a way that completely ridicules the then-received ideas of cultural authenticity.

Bolan had opened the door, and both Bowie and Roxy rushed through into the open space. In the place of hippie detritus came a whole flood of gnostic, hermetic references from 1960s fine art, outsider gay subcultures, avant-garde literature and two decades of teen-culture history (‘you’re so sheer, you’re so chic, teenage rebel of the week’). These were distilled into huge hits that inspired a generation. Beginning as ideas and thoughts about pop culture, they became pop.

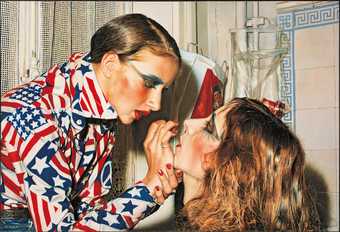

Franz Gertsch

Marina making up Luciano 1975

Oil on canvas

234 x 346 cm

Between 1972 and 1974, Glam bossed the British charts. It’s usually thought of as a frivolous pop moment – a bit of kitsch from an earlier, simpler time – but it was much, much more. It deserves to be seen as a true, ground-breaking aesthetic, as important as Mod or Punk. The 1960s were over: Glam initiated a new approach for a new decade that elided gender distinctions and crashed the barriers between high and low culture, fine art and street style. It also marks the moment when post-war pop culture finally moved from modernism – the notion of a unitary forward motion that had informed both high 1960s Mod pop and the political ambition of the counter-culture – into what would later be called postmodernism. Glam was nakedly eclectic. Freely plundering ideas and images from 50 years of popular culture, it was gleefully disrespectful to its sources – everything was grist to the mill, provided it was fun. That was Glam’s liberation.

Post-hippie pop culture had, by 1971, become dreary: the mode was confessional singer-songwriter; the style downbeat denim. Bowie put his finger on it in an interview with Cream magazine:

Marc Bolan is the new angry young man. Marc Bolan has that angry young life. You can quote me on that. I also like Iggy Stooge and the Flaming Groovies. Rock should tart itself up a bit more, you know. People are scared of prostitution. There should be some real unabashed prostitution in this business.

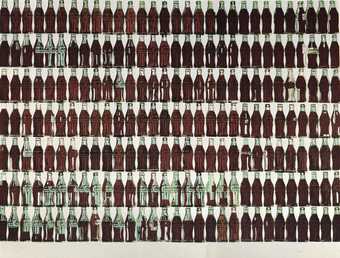

One of Glam’s defining influences was The Factory of Warhol and the Velvet Underground, underexposed in the UK during their 1966/7 peak. Bowie was among a small group dedicated to their ideas. During 1971 he visited The Factory and met Warhol – an event captured on videotape. That same year, the Velvet Underground back catalogue was reissued to rave reviews, while Warhol’s Pork, a play edited from his telephone conversations, opened in London to tabloid outrage.

Tim Mara

Power Cuts Imminent (1975)

Tate

The Factory had always been a haven for gay outcast attitudes. By the early 1970s, Warhol had moved on from the hard-core A[amphetamine]- heads such as Ondine to drag queens and transgender pioneers such as Candy Darling, Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis (beautifully photographed by Richard Avedon for Vogue in 1972). These were the new superstars promoted in Interview magazine, which became a major focus for this new aesthetic with its concentration on glamour past and present. All of which tallied with radical gender-fuck trends in gay culture itself – most notably with the San Franciscan theatre troupe the Cockettes (seen in photos by Michel Auder and Peter Hujar). In many ways, this was a continuation of the work pioneered by Jack Smith, whose 1963 film Flaming Creatures and later untitled artworks pushed flagrant campery and graphic sexuality into cosmic fusion tendencies – a boundless queer style where everything merges and blends into a new vision.

Bowie used some of these ideas in his assault on British pop culture during early 1972: most notably in his February interview with Michael Watts of Melody Maker, during which he proclaimed himself to be gay. Five years after homosexuality had been partially decriminalised, he was the first major performer to ‘come out’. And it didn’t harm his career: indeed, his first Top of the Pops performance of Starman was saturated in queer poses and references.

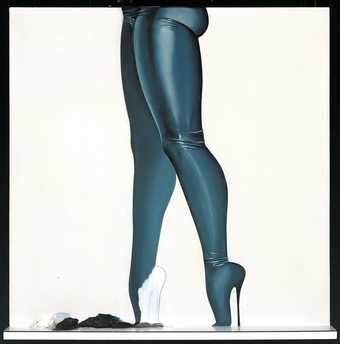

Allen Jones

Wet Seal (1966)

Tate

Those who criticise Bowie for leeching off gay culture – there was controversy a few years later when he appeared to retract his comments – totally miss the point. Glam was overwhelmingly concerned with pleasure, play and dissolving artificially created or restrictive hierarchies in art and life. The fact that a major star could be gay, or at least bisexual, proved liberating for many performers, who, in accessing their inner queen, were able to explore different topics and styles. And there were many spin-offs in the fashion and fine art worlds. In between their celebrations of gay freedoms, explorations of a mystical England and psychogeographical investigations of hidden London, Derek Jarman’s early 1970s Super 8s act as a kind of insider diary, covering such topics as Bill Gibb’s fashion show (1974) and various portraits of Andrew Logan, artist and creator of the social drag competition the Alternative Miss World.

Whether it was Bowie’s Lindsay Kemp-inspired mimetic gestures, Roxy Music’s super-stylised album covers, or the Alternative Miss World, Glam celebrated the Pose. The idea was that the artist could become the artwork; that the sculpture could be taken off the plinth: that it was possible to make yourself over with pseudonyms and extraordinary clothes – a very Warholian, indeed Pop Art concept this. The drive was towards permanent transformation, a potent pop-cult motivating force. These manifestations paralleled the work of Gilbert & George, as well as the performance artist and painter Bruce McLean, who developed his Pose Work for Plinths – a series of contortions from 1971 (which strangely prefigure Bowie’s cover for 1979’s Lodger) – into a full-blown fake band by 1974, Nice Style, who at the time were described as ‘a cross between the society slicker and the TV ad action man of the kind who delivers the chocolates against all the odds’. Sounds like a Roxy lyric.

Glam introduced a decade’s worth of radical art school ideas and practice into the pop mainstream, which fed back into the art world itself. Bryan Ferry’s Newcastle art school milieu had strong links with both Warhol (thanks to Mark Lancaster) and Richard Hamilton (who taught at Newcastle between 1953 and 1966). Virginia Plain began life as an early 1970s Ferry painting, ‘a surreal drawing of a giant cigarette packet, with a pin-up girl on it, as a monument on this huge Dalíesque plain’.

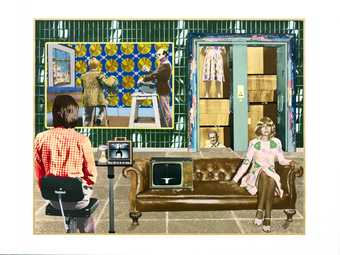

Richard Hamilton

Fashion-plate (1969–70)

Tate

Roxy saxophonist Andy Mackay studied at Reading Art School, where he was exposed to major modern composers such as John Cage and Morton Feldman, as well as Joseph Beuys, the Dadaists, the Pre-Raphaelites and the English decadents. Among his contemporaries were Anne Bean and Polly Eltes, who later formed the fascinating crossover performance art/ rock band the Moodies – best seen in some wonderful 1974 photos by Joe Gaffney, doing the Pose in a blasted, derelict London landscape.

Around two and a quarter minutes into the Top of the Pops performance of Virginia Plain, the synthesiser solo kicks in, and finally the instrument comes into plain view – a keyboard and a curious sequence of dials and knobs, played by a pair of lurex gloves. You don’t see Brian Eno in close-up throughout, but his presence is felt – as a random noise generator, as constant electronic pulse, as an idea and a look that does not yet have a name.

The futuristic side of Glam was fantastically important, as that – apart from its gleeful spirit – was what propelled pastiche into something powerful and exciting. Some of the ideas were retro-futuristic – a 1950s ideal of a jet-packed Jetson future – but others took directly from the artistic avant-garde of the day. At Ipswich Art School, Eno had been taught by Roy Ascott, whose method aimed to ‘shake up preconceptions and established patterns’. This was far from any standard art education: at once a happening, an experiment in behaviourist practice and an interdisciplinary fusion of cybernetics, sociology and scientific systems building. As Michael Bracewell observes in his book about Roxy Music, Re-make/Re-model: ‘As with computers, robots, atomic bombs and jets, the technologies designed during the second world war would become the futuristic emblems of the new pop/space age.’ Hence the EMS VCS3 synthesiser.

Bruce McLean and Paul Richards

Nice Styles: Glam Rock Performance 1974

Colour photograph

Eno talked about its qualities in a 2010 Guardian interview:

It came without any baggage… When you play an instrument that does not have any… historical background you are designing sound basically. You’re designing a new instrument. That’s what a synthesiser is essentially. It’s a constantly unfinished instrument. You finish it when you tweak it, and play around with it, and decide how to use it. You can combine a number of cultural references into one new thing.

Between 1972 and 1975, Bowie and Roxy Music pursued a course of constant reinvention through the pop charts – an extraordinarily confident curve of change and growth. At the same time, Glam’s influence spread back into the artistic avant-garde– the high conceptual performance art of General Idea, the poses of Bruce McLean and the visual diaries of Derek Jarman, whose Duggie Fields At Home captures the artist on the cusp of 1940s/1950s retro, just as Art Deco turned into Austerity Binge.

By this time, the lessons had been learned well. Perhaps the most extraordinary part of the whole Glam story is how Bowie and Roxy Music, with their elite messages, gender play and formal sophistication, had became a cult among working class kids in the midst of the worst depression for well over 30 years. Just watch John McManus’s extraordinary 1976 short Roxette, which features teenage stylists in their finery, proudly posing in the dark and the murk of post-industrial England.

What was make-believe had become real.