Since the mid-1960s, Sylvia Sleigh famously depicted male sitters naked, often knowingly referring to classic paintings of women from art history. Not unlike Edouard Manet’s displacement shock tactics that you find in his Olympia 1863 and Le déjeuner sur l’herbe 1863, she made use of familiar tropes to introduce a sense of unease and surprise. At a time when feminist discourse was emerging, this was designed to highlight social and historical gender inequalities on the level of what is or is not deemed to be an acceptable representation. In this sense, her art historical quotation is never directed at the connoisseur, but is rather used as a tool to induce through the viewer’s memory of famous paintings some estrangement effect – what Brecht called ‘distantiation’ – in order to show that what we perceive as natural is, in fact, an ideologically charged convention.

In addition to the political and social intention in Sleigh’s approach, I would say that defining her as a realist painter is certainly accurate, but it might not account for a big part of the fascination that her pictures attract. When you are in front of them you immediately understand that her way of looking is very personal and emotionally vivid. We could call this ‘ultra-realism’, a certain ability to inscribe on to the canvas an element of heightened perception in such a way that it is totally evident. This more-than-real representation is certainly rooted in the relationship the artist had with her sitters, most of whom she knew well in New York, making her emotional gaze, rather than the photorealist representation, the centre of the work. What we are presented with is not a re-presentation, but a method for apprehending in the original meaning of the term: a way of ‘taking in’ the world that is extremely personal and generous.

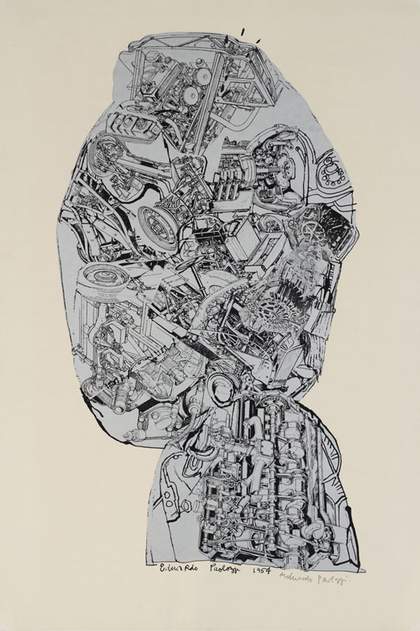

Sylvia Sleigh

Eleanor Antin 1968

Oil on canvas

114.3 x 152.4 cm

Sleigh’s backgrounds are interesting too. The use of patterns (as part of the furniture’s fabric, the wallpaper or an exuberantly mature garden) in many of her paintings is similar to an optical effect that flattens the works’ quasi-abstract background. The result is that these painstakingly detailed bodies seem to pop out of the canvas, the perspectival illusion being mainly believable for the figures in the foreground only, making them hyperreal. The artist’s intention was clearly to work against the perceived ideas of the idealised portrayal of desirable beauty.

Often she depicted her subjects as saints, or other religious or mythical figures. Here again we see her working against the idealisation with which the Western tradition has invested mythological or religious narrations. In Sleigh’s pantheon, the 1960s and 1970s Beat generation are treated as an all-too-human version of a very personal mythology, one based on intimacy rather than a sacred tale outside of human history. Her practice is easily associable with the Pre-Raphaelite visual vocabulary, precisely because her intention is a reversed and mirrored version of it. In Annunciation: Paul Rosano 1975 she clearly portrays a dissonant subject as an angelic figure. In the series of Imperial Nudes or Eleanor Antin reclined in a Venus-like pose we see Sleigh’s contemplation and true love for everyday life. This reaction against the tradition of monumental history and its propagandistic relation to mythology embodies an ethical attitude which I think has great resonance with the practice of younger artists such as Wolfgang Tillmans, Jason Dodge or Frances Stark.