Daniel Sinsel on Piero Manzoni’s Achrome 1958

Frau Krauss was a colleague of my father and a family friend. She would look after me sometimes after school. The smell of her cooking and the heavy oak furniture popular in 1980s Bavarian interiors were unlike what I knew from my own home. A framed print above the dining table encapsulated this unfamiliar world. I remember dusty feet and shiny grapes. I conclude now that it must have been a copy of a work by Murillo. His painting Boys Eating Fruit (Grape and Melon Eaters), from 1645–6, seems to come closest to my imprecise, yet strong memory. It appears a fitting choice for a Catholic home in its appeal for humility and charity. Hungry urchins devouring a melon and grapes are easily forgiven for their excesses.

My prepubescent memories are replaced the moment I glance at the painting on the internet. I can only guess why this image held so much importance. I don’t remember ever asking anyone questions. I must have known then that paintings and secrecy have a pact. Who were these dark-skinned boys with ripped clothes? Why did they eat grapes and melon like this? What did I know about them? What did I know about myself?

I stand in front of a Manzoni Achrome. Ripped cloth, dipped in kaolin, white and dry like dust of the mind. I drench it with as many uncatholic juices as I like. Everything is absorbed, any intemperance vanishes before my eyes. What did Manzoni know about the world?

Piero Manzoni

Achrome (1958)

Tate

Achrome was purchased in 1974.

Jonathan Allen on Fischli & Weiss’s Untitled (Tate) 1992–2000

Peter Fischli and David Weiss

Untitled (Tate) (detail) 1992–2000

Polythene foam, acrylic paint. Display

Dimensions variable

© Peter Fischli and David Weiss

Voice

Good afternoon. Lo Stivale.

Jonathan Allen

Hello, good afternoon… I have a slightly unusual question. I was wondering if you own, or have ever owned, a restaurant in west London?

Voice

No, we’ve always been in Cobham. Why do you ask?

Jonathan Allen

Well, okay… I’m standing in Tate Modern, the art gallery in London, looking at a very realistic sculpture of a pizza box. It’s got the name Lo Stivale on the lid, and I’m wondering if the artists just made up the name, or if the place actually exists. The box says the restaurant is in west London, but you’re the only pizza place called Lo Stivale that I can find anywhere.

Voice

[laughs] Is there a map of Italy on the box?

Jonathan Allen

Yes, as a matter of fact there is, and a cartoon of a chef pulling a pizza out of an oven.

Voice

Stivale is the Italian word for boot… a lot of Italian businesses use the name because of the shape of Italy.

Jonathan Allen

Ah… I see. Are you Italian?

Voice

No, Persian, but we just liked the word [pause]. So, do you want to order a pizza?

Jonathan Allen

But Cobham is more than twenty miles from here!

Voice

Well, if you can wait a couple of hours… what kind of pizza would you like?

Peter Fischli, David Weiss

Untitled (Tate) (1992–2000)

Tate

© Peter Fischli and the estate of David Weiss, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York

Untitled (Tate) was purchased with assistance from Tate Members and Tate International Council and The Art Fund in 2007 and is on display at Tate Modern until 14 February 2011.

Simon Wallis on Barbara Hepworth’s Pelagos 1946

Barbara Hepworth

Pelagos (detail) 1946

Part painted wood and strings

43 x 4 6x 38.5 cm

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Hepworth’s Pelagos 1946 reminds me of the swell, power and fascination of the sea, which has always been important to me, as I grew up on the coast in Brighton. My friends and I were drawn to the sea every day to play on the tar-splattered beach, escape family rows, clear our heads, or collect unusual stones. We night-fished, sunbathed and gathered on the beach after clubbing. I worked the deckchairs and kids’ fairground rides.

In the summer we pumped up lorry tyre inner tubes and manoeuvred unsafely out into the swell. The water was always freezing, and a bit polluted, but we didn’t care, even though we accidentally swallowed plenty of it. However, the winter was my favourite season with its churning, violent sea and empty beaches.

All the action in this sculpture seems to be hidden and happening on the inside, as though a wave is on the cusp of breaking. The interior’s luscious shade of cool light blue is set off by the beauty of the nut-like exterior form in elm wood. The sculpture doesn’t reveal itself all at once; you can spend time contemplating its formal and associative relationships.

The strings make me think of Brighton’s piers – structures I loved. I was fascinated by them being partly submerged, rusty and barnacle encrusted, but enjoyed also the sense of relief they offered through looking out to the sea’s empty horizon, as if leaving England. I’d glance back to see the city at a good distance stretched out behind its motley façade.

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Pelagos (1946)

Tate

Pelagos was presented by the artist in 1964.

Fred Grose on Julius Bissier’s 20 Jan. 59 Zurich 1959

Julius Bissier

20 Jan. 59 Zurich 1959

Tempura on fabric

20 x 23.5 cm

© DACS, London 2011

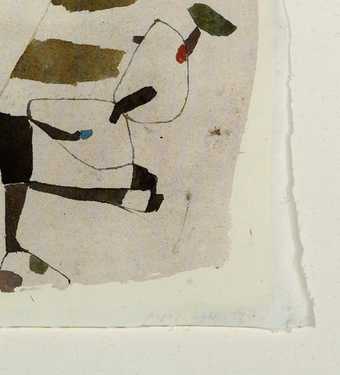

I’ve known and been entranced by Bissier’s painting since about 1979, and cannot explain why. Yet the more I look at his work, the greater the fascination grows, and the why doesn’t matter.

I suspect that, on 20 January 1959, Bissier was gazing despondently at a blank piece of fabric he had prepared for a painting which failed to materialise; his creative vision appeared lost. Hoping to trigger some inspiration, he hesitantly designed the dominant but rather depressing green shape on the left, tentatively adding the adjacent small black vertical rectangle which would prove to be the foundation of a painting within the whole.

Bissier’s interior world, in which his creativity resided, slowly then awakens, giving rise to the shapes and lines that are to flow, almost unimpeded, as though arising from their own agency. The vertical leg shape appears, followed by the horizontal from one of the attached shapes; lines wind their way to form the two ovals, which crown this work, to be perfected by the few minor, yet important, additions.

The diagonal movement creates a captivating eye-path as it enters and leaves related areas, as well as providing a balance for the whole, with the central construction forming a puzzling entrapment for my eye.

Thus, a separate work of art has been created within the whole (as well as the whole itself ), each item appearing to be constructed by its own unrestricted and unguided flow, yet, in actual fact, a product of one man’s skill.

Julius Bissier

20 Jan. 59 Zurich (1959)

Tate

20 Jan. 59 Zurich was purchased in 1960. It is currently not on display.