Tate Britain’s Henry Moore exhibition is the first extensive survey of the artist in this country since the Royal Academy show in 1988, and demonstrates that his work has a sharper edge than has been previously acknowledged. Investigating non-European art was important for Moore, and exploring Surrealism even more so. He was excited by the sculpture revolution in Paris around 1930, led by Giacometti and Picasso, but his objectives were personal. Moore’s was not a Surrealism of the marvellous, with its incongruous encounters and freedom from conventional restraints, but a refined poetic – a search for fresh and vivid expression through traditional sculptural materials. His was an intelligent understanding of Paris, but he brought new ideas into play with judiciousness.

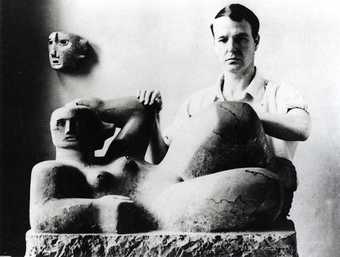

Up to 1950, the sculptor confined himself mostly to carving natural materials to a high degree of finish. His multi-part carvings of 1934 such as Head and Ball and Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure pick up on Giacometti’s revolutionary switch of sculpture from the vertical to a ground- or table-hugging horizontal, but Moore uses the device with different expressive intentions. His Surrealist period sculptures refer to the human figure, animal forms and stone and bone shapes. They are disturbing in their Surrealist concern with metamorphosis, with process and change as principles of his work and not incidental characteristics. An outcome is the difficulty of identifying with certainty exactly what the subjects of his pieces are, while being able to reject with confidence the possibility that their purpose is abstraction. Abstraction was a tool, not an objective. His development is gradual and measured, with ideas kept in mind and often returned to. His preference in the first half of his career for traditional techniques and materials, carving in wood and stone, highlights a desire for continuity rather than rupture. It is difficult to see Moore as an urban artist, not only because of the ways he used natural materials and how his sculptures frequently referred to landscape, but also because he was only intermittently concerned with the disruptions and discontinuities of urban life. His work, like that of other British artists of his generation, engages with the question of what modernism may mean when it turns its back on modernity. It is often in the enigmatic imagery of his technically complex coloured drawings of the late 1930s and 1940s that the pastoral is forcefully discarded in favour of work that reflects fear and anger, a sense of reversion to the primitive.

Moore’s core concern was the human figure. Heads, especially eyes, are focal points in many earlier sculptures, exposing the limited truth of criticism, based on later work, that his ‘pin-headed’ figures show a lack of interest in the human face. Several of the wall-mounted stone masks of 1927–30, inspired in part by Pre-Columbian art, have deep-cut eye sockets in the form of mysterious holes. He made removeable stone eyes which he slotted into some sculptures. Girl with Clasped Hands 1930 still has eyes in place, made of stone that contrasts with the main body of the sculpture. The profile Head in slate of the same year has a single hole to represent the empty eye socket. But there is good evidence to show that Moore experimented here too with an eye which was stuck in initially with plasticine and subsequently rejected. Later he preferred to stress the formal qualities of holes in his work, but at least to start with, it was their capacity to intensify expression that mattered most. In the series of torso figures and mother and child sculptures in the early 1930s, he attends especially to hands: clasped hands, clutching hands, hands that touch and cradle. He was sensitive to the fragility of the human body, but also its strength.

In the late 1920s Moore began collecting stones, bones, crustaceans and any natural object or fragment that appealed on account of its shape. While a student at the Royal College of Art, he had spent time in the nearby Natural History Museum. His fascination with the beginnings of life and the prehistoric origins of art fed into a feeling for the equivalence of different forms of life and led between 1930 and 1932 to a series of what have become known as ‘transformation drawings’. Up until then his drawings had largely been figure studies, many of them life drawings. He now more or less abandoned life drawing in favour of this more radical direction: the images are near abstract, and show pebbles, stones and bones in the process of becoming human figures or parts of figures. The small pencil drawings executed in continuous curving lines are close to automatism without giving a sense of wholesale surrender of intention. He could start by drawing a mammoth’s jawbone and end with a reclining figure. He might turn the paper round as he worked, and there might be intervening images, sometimes on the same sheet. These were not experiments for their own sake. Several culminated in sculptures which, like the drawings on which they are based, are founded on the principle of metamorphosis. Moore digs deeper into Surrealism, his distortions of the body becoming more extreme: Composition 1932, in African wonderstone, is a semi-amorphous form with protruding eyes, possibly human, possibly animal. It is jelly-like, and gives the sense of a soft object created in a hard material – seeming to contradict the artist’s much discussed belief in ‘truth to materials’.

Moore’s interest in metamorphosis was an aspect of Surrealism, certainly, but his shift in direction at the beginning of the 1930s was especially informed by the new inter-connective biology of J.B.S. Haldane, which argued that the origins of life and development of organisms could not be accounted for either mechanistically or through the kind of ‘life force’ implicit in vitalist theory. Haldane was concerned with interaction between organisms and their environments over time. He was reluctant to define a particular point at which life emerged from pre-life, implying that animate and inanimate, or one species and another, might at an early point in their development be hard to distinguish. Moore was a keen and versatile reader, but this is not to assert that he was drawing directly on a specific body of scientific ideas. It was more that his mind was quick to respond to new ideas picked up in books, magazines, or simply conversation. He had his own ways of developing such a fundamental Surrealist principle as that of transformation. His constant concern with ideas of origins (such as mother and child) and pre- and early history (a constant return through the 1930s to the subject of standing stones) has parallels among Parisian artists, but they are developed with the help of sources such as the new biology which were substantially British. Moore’s approach to Surrealism changed in the mid-1930s and much of his contribution to it was at that point invested in drawing. The word ‘drawing’ itself acquired a different meaning for him: while the transformation drawings had been process-based, predicated on change, those made in the late 1930s and through the 1940s are more pictorial and equivalent to paintings. As Five Figures in a Setting 1937 shows, they are still connected with his sculptures, but the images are distortions or reworkings of sculptures recognisable as his, and the overall effect is different because Moore had free use of colour – which he never employed in sculpture beyond what his materials already possessed. In the new drawings he could use a lurid pink to suggest flesh, faces and tongue contact. Alienated, sexual, transgressive and occasionally malignant, the images are characterised by a kind of entropy or defacement.

That is true of a drawing such as Stones in a Landscape 1936. While the stones resemble forms he might have made in sculpture, their ambience and the penumbral light, which are unrealisable in sculpture, create a monstrous effect. Moore shared the darkened imagination of Surrealism in the shadow of war, but brought it to life in a highly personal way. The underground drawings of Londoners sheltering from the blitz have a unique place in Moore’s work and in the rapid growth of his reputation after the Second World War. They have been seen as a commitment to public service in wartime – the sculptor turning his back on modernism, and establishing the basis of a more popular art by means of drawings that directly reflected reality. Some of this is fiction. A careful look at the work of other artists who drew in the shelters, or at the photographs of Bill Brandt, shows the distance of Moore’s shelter drawings from reality. They tend to be carefully composed as if he were mindful of Italian Renaissance compositions, and portray little of the untidiness and picturesque detail of life in the shelters. He took on only projects he wanted to do, and was not, as has been suggested, cajoled by Kenneth Clark, chairman of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, into war work. On the contrary, he saw in Londoners sleeping on station platforms a subject that fitted with his existing reclining figures and with the nocturnal feel of much of his Surrealism. The recumbent figures in Tube Shelter Perspective: the Liverpool Street Extension 1941 are ambiguous images suspended between life and death: they can be read as sleepers, as funereal effigies, as corpses retrieved from some disaster and lined up in a temporary morgue, or simply as a dictionary of Moore’s already existing reclining figures. They are both real and imagined, alive and dead, constituting a new kind of dream world, still within the context of Surrealism, and with a new take on the Surrealist delight in metamorphosis. Nor is it true, as has been said, that his shelter drawings were immediately popular. Supportive critics spoke favourably, but press reports show that occupants of the shelters sometimes felt they were being mocked. The sculptor’s letters recount that he was appalled at the filthiness below ground and had little more affection for his subjects (in the conditions in which he saw them, at least) than they for his work. Moore certainly gained in reputation, then and later, from the much improved support from post-war British art institutions than earlier artists had received. But the officially sponsored exhibitions at home and abroad that ensued, and the positive critical commentaries accompanying them, though benefiting Moore, as well as younger artists and British sculpture in general, brought a cost with them. In terms of the shelter drawings, the payback was the creation of a belief that he was an artist ordinary people could appreciate without a deeper engagement with difficult art because they recorded actual events at a desperate moment in British history. Actually, they are among the most potent and original of his works, nurtured on the Surrealist principles of ambiguity and metamorphosis. The Royal Academy’s Henry Moore exhibition in 1988 was already in planning when the artist died two years earlier. It was a memorial show, even if not conceived as such, and the cover of the catalogue had a detail of the Madonna and Child of 1943–4, commissioned by Canon Walter Hussey for St Matthew’s Church, Northampton. The sculpture was included in the exhibition even though it is a solid block of stone five feet high and hard to move. It is a conservative piece and its relationship to early Renaissance Italian church sculpture bears out the objective Moore stated more than once that he wanted to ‘make sculpture that would stand beside the great sculpture of past ages and masters’. For whatever reason, it is not in the exhibition at Tate Britain, and its absence pinpoints a key difference between the two shows. The Tate’s is an intimate Moore, tending to avoid the public side of his work, leaving us to enjoy his varied and searching imagination.