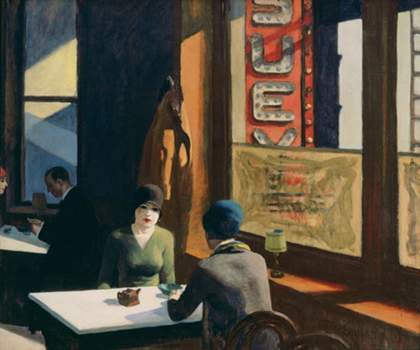

I’m sitting in a hotel room in Massachusetts thinking about the past three days I have spent driving around looking for a location that feels like it is nondescript, but is very particular. In other words, I have been searching for a sense of the American landscape that is linked intrinsically to Edward Hopper’s vision.

Hopper has been a huge influence on me. His work is grounded in an American sensibility that deals with ideas of beauty, theatricality, sadness, rootlessness and desire. It is now virtually impossible to read America visually without referring back to the archive of photography and cinema that has come from Hopper’s paintings. His art has shaped certain essential themes and interests in so many contemporary painters, writers and, above all, photographers and filmmakers.

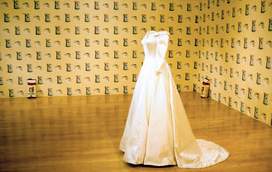

Cindy Sherman

Untitled Film Still #48 (1979, reprinted 1998)

Tate

He used to liken his own paintings to the single frames of films. There is always a suggestion of framing in his pictures, whether it’s windows, doorways or shafts of light, but the single frames he refers to are also very much about the fragment. Hopper’s narratives occur in moments that are forever suspended between a ‘before’ and an ‘after’ – elliptical, impregnated moments that never really resolve themselves. There is an enormous reservoir of psychological anxieties in his work, a sense of stories repressed beneath the calm surface.

You get that feeling in Todd Haynes’s film Safe 1995. There is a night scene in a bedroom between a husband and wife. They are sitting on opposite sides of the bed and facing away from each other. There is this enormous gulf between them, which is amplified by Haynes’s use of distanced camera takes. It feels very stationary and photographic. The sense of alienation is also there in the way he uses the interior of the room – the mirrors, the architecture, the décor. You can trace such a scene straight back to Hopper. Everything in a Hopper painting, his interiors in particular, is full of meaning that propels the narrative. It’s the telling detail, whether it be a suitcase, a book or a bed, that is really important. Every artist creates his or her own vocabulary, a microcosm where motifs appear and re-appear, revealing certain obsessions. It’s amazing how many of Hopper’s pictures feature something as simple as a bed, windows, or doorways. I think this serves to emphasise further the viewer looking with a kind of voyeuristic gaze into the world. It is an idea that Hitchcock used in Rear Window 1954 where you have people looking out from one private world into another. Hopper’s figures are often seen peering through windows or into the landscape. Ultimately, I believe the window creates the possibility of another existence outside their own. He’s not only showing us alienation, but also a degree of hopefulness.

And there is an extraordinary sense of light in Hopper’s work. On the surface it appears to be realistic, but there is something particular about his light that, to me, makes his paintings feel more psychologically-based. There are these very ordinary situations, and the light is being used as a narrative code to reveal the story. It also provides some possibility of transformation of the ordinary, which gives the images a certain theatricality. Steven Spielberg picked up on this and used it very well in Close Encounters of the Third Kind 1977. In the film there is a collision of the themes of the paranormal and the strange confusion of nature and domesticity. It is also there in Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Magnolia 1999, particularly in the scene that culminates in a rain shower of frogs.

The idea of theatricality is prominent in American visual culture. I think it has something to do with the nation’s fixation on artifice. There is a mix between artifice and everyday life. In terms of art, this notion of the uncanny is grounded in a defined angle on realism. Hopper’s is not a conventional realism, but a psychological one. (You can see it also in John Currin’s paintings and Robert Gober’s sculpture.)

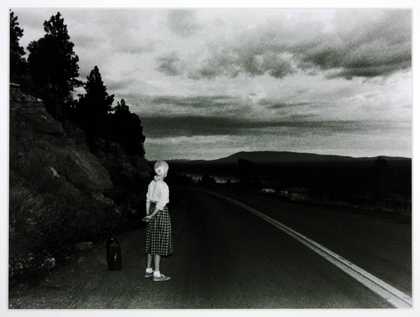

Hopper’s landscape painting has also been enormously influential for several generations of figure photographers (I have always joked that he is one of the most important photographers), from Diane Arbus and Robert Frank to Cindy Sherman’s early black and white film stills and Philip-Lorca diCorcia. In particular, he has had a major impact on the way American landscape and exterior spaces have been photographed.

Joel Sternfeld

McLean, Virginia, Dec 1978 1978

Photograph

Photo courtesy The Photographers’ Gallery, London © Joel Sternfeld and Luhring Augustine, New York

The artist was very much drawn to these American vernacular spaces, where there is a sense of the familiar and the ordinary. His work feels as if it can be everywhere and nowhere; it is less about a particular place, and more about a collective imagination. Many people equate Hopper with suburbia, but most of what he painted was in New England. There’s something about the way he depicted the Cape Cod houses, for example, that has resonated with people nationwide. One also gets this sense of mobility and isolation. Moving out of a small town situation, the migration west, the road trip – these are all very much part of the American psyche. Joel Sternfeld, Stephen Shore and the topographic photographers such as Robert Adams have all picked up on his interest in the American vernacular.

Photographers and filmmakers have engaged with a duality that is at the heart of Edward Hopper’s art – he makes it a both very beautiful and sad world. I think that duality is the key aspect of his work, and why so many have been affected by it.