Ed Ruscha on Covered Car – Long Beach, California 1955–6

Seeing The Americans in a college bookshop was a stunning, ground-trembling experience for me. But I realised this man’s achievement could not be mined or imitated in any way, because he had already done it, sewn it up and gone home. What I was left with was the vapours of his talent. I had to make my own kind of art. But wow! The Americans!

Robert Frank’s landscape covers all of America. Whereas my so-called mapping of space – from the early swimming-pool series to the City Grid works – probably comes out of my interest in Los Angeles and seeing it from above, as if from an airplane, to give oblique visions of the city.

Robert Frank on My Father’s Coat 2000

After my father was buried in 1976 in Zurich, my mother gave me the coat: ‘This is your father’s coat. It is very good, warm and not worn at all. Please take it with you to New York and wear it.’ I hung up the coat in a small room in our house – with all my film cans on the window sill and an Aloe plant (needs a little water). The door is closed. I did not wear the coat for many years. As time goes by I am thinking more of my father and how I might become more like him.

On 14th Street I buy a Russian Lenin medal with shining red star. The medal looks good on the coat – it changes everything. The coat stays with the plant and film cans. When I am in New York on a cold day I wear the coat with the medal. The writing under the photograph is like sending a postcard – the medal on the coat an imaginary past; the plant is alive and waiting and growing. and I am getting old.

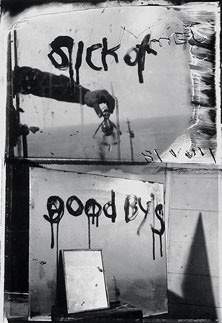

Lou Reed on Sick of Goodby’s 1978

Robert Frank

Sick of Goodby’s, Mabou 1978

Gelatin silver print

48.3 x 33 cm

Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

© Foto museum Winterthur/National Gallery

I was looking at Robert Frank’s photograph Sick of Goodby’s in his book The Lines of My Hand. Moments before I had been listening to a Johnny Cash song called I Wish I Was Crazy Again. Then I thought of the goodbyes in the book to old friends caught once and for all and never again to be seen in life, and I was struck by the intensity of the sadness of life and its redeeming qualities as reflected in these moving photos. With Johnny Cash as well, the desire to see it all again, to go out one more time into the wild flame only to be burned up forever and never be seen again except in these farewell photos, is moving beyond description. The photos speak of an acceptance of things as they are. the inevitable death of us all and the last photo – that last unposed shot to remind us of our friends, of our loss of the times we had in a past captured only on film in black and white. Frank has been there, and seen that, and recorded it with such subtlety that we only look in awe, our own hearts beating with the memories of lost partners and songs.

To wish for the crazy times one last time and freeze it in the memory of a camera is the least a great artist can do. Robert Frank is a great democrat. We’re all in these photos. Paint dripping from a mirror like blood. I’m sick of goodbyes. And aren’t we all, but it’s nice to see it said.

Liz Jobey on Sick of Goodby’s 1978

In the early 1970s Frank returned to photography after more than a decade of making films. In 1958 he’d produced a series of pictures in New York City from a bus. ‘These photographs represent my last project in photography,’ he wrote in The Lines of My Hand, his retrospective book published in 1972. ‘When I selected the pictures and put them together I knew and I felt that I had come to the end of a chapter. And in it was the beginning of something new.’

New beginnings mean leaving things behind. Moving through Frank’s photographs that is always what comes across most forcibly: the urge to go forwards – not so much in optimism as a way of staying alive – and the sadness of what has been lost. Hold Still – Keep Going, Life Dances On, Home Improvements, Moving Out: the titles of his pictures and films are heavy with that emotion. Moving Out is a triptych of three abandoned rooms. Underneath, stamped out in red packing-case type, is the legend: ‘Forgotten possessions in John Turner’s final room, Long gone shadow of marriage on Third Avenue loft, Last look at my parents’ Wohnzimmer in Zurich.’ Life as a series of rooms passed through; people and possessions left behind.

Photographs, in themselves, are memories, always about the past. ‘You know, photographs immediately make everything old,’ Frank told Ute Eskildsen, the director of photography at the Folkwang Museum, Essen, in 2000. ‘You do your work as a photographer, and everything immediately becomes past. Words are more like thoughts: the photographer’s picture is always surrounded by a kind of romantic glamour – no matter what you do, and how you twist it.’

When he returned to photography in the 1970s Frank had abandoned all the formal, classical unities of the single image. The aesthetic of film had intervened. The physical appearance of his pictures was radically changed: there were few single images, instead there were composites and serial frames, taped and spliced together with words scratched on the negative or scrawled in dripping paint on the picture itself. He had destroyed the photograph’s superficial descriptive powers and used it as a surface on which to etch his emotional shape: gnomic phrases, half-articulated thoughts, sometimes the words barely decipherable, and yet they described, in a way that photography had not done so powerfully before, intense, painful, personal emotion.

In 1955, in his application for a Guggenheim grant to support what would become The Americans, Frank had written: ‘What I have in mind, then, is observation and record of what one naturalised American finds to see in the United States that signifies the kind of civilisation born here and spreading elsewhere.’ In his later pictures, he wanted ‘to show how I am, myself… to show my interior against the landscape I’m in’. In 1970 Frank and the painter June Leaf bought a house and land in Mabou, Nova Scotia, where many of his later photographs and films would be made. The landscape of Mabou in itself was a metaphor: a place on the edge of the continent where nature is at its most extreme and most intact; where the distance between heat and cold, light and dark, hope and despair is most intense; where existence is more tangible, more hard-won and might be questioned itself for reasons to give up or carry on. The later pictures are confessionals, many of them expressions of private grief, and this is Frank’s gift – to expose himself emotionally in his photographs, sometimes in a way that makes them almost too painful to look at.

In 1974 his daughter Andrea died in an air crash in Peru at the age of twenty. The year before, his friend, the filmmaker Danny Seymour, disappeared and was presumed dead. His first marriage was over. His relationship with his son, Pablo, was difficult. We know all these things because Frank made pictures about them: fractured, stuttering, abstracted images, using snapshots and half-shots collaged into disjointed sequences as if bits of footage from his memory bank had been transferred directly on to paper.

Sick of Goodby’s is full of reflecting planes. The small skeleton figure of the man is held out above water, his body hovering on the horizon between the sea and the sky. The small cross is familiar from other Mabou pictures, particularly the one Frank made the year before, in 1977, as a memorial for his daughter Andrea, where the telegraph post stands against the sky like a monument. Sick of Goodby’s is a picture of emotional exhaustion. The date is scrawled in reverse at the bottom, but what does it say in the top corner? You take a mirror to try to read it. ‘I am…’? Still not clear. A photograph is a mirror. In it you might examine yourself for signs of emotional wear and tear; to see how life is leaving its mark. In this picture is all Frank’s weariness. Too much has gone. He said: ‘I have a lot in back of me – of what has happened in my life – and that’s a tremendous pull backward. And in front of me I love the sea.’

Mary Ellen Mark on Political Rally, Chicago 1956

Robert Frank

Political Rally, Chicago 1956

Gelatin silver print

© Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

I first saw this photograph in his The Americans when it was published in 1959. The book is still an inspiration to me. Robert Frank is a purist. He is so honest in his observation and he doesn’t manipulate what he sees. He is able to describe the essence of everything he looks at, whether it’s people on the bus, a barber’s shop, or a covered car. He brings the feel, smell and sense of what a place is like.

In this picture, Frank did something that was daring at the time, which was to cut off part of the subject. I think he really understands the fact that sometimes an image is about how much you leave out of the frame. If it were just the man with the tuba alone, it wouldn’t be as strong. The cut frame gives a sense of spontaneity. Frank creates movement with his camera and his subject in a truly original way. He’s a narrative photographer. Looking at his pictures is like watching a part of film; you can imagine what is happening around the frame.

He uses the flag a lot in his work. It is such an iconic and symbolic image and he is very aware of that. It features in other photographs of the time, such as Parade – Hoboken, New Jersey, where it obscures the face of one of the people standing at the window. In 4th July, New York 1954 the light goes through the flag. And in Bar, Detroit 1955 it takes on a surreal quality as if hanging in mid-air.

His pictures are often about isolation. You can feel that loneliness. It is very much a feeling of America. It’s a tough country, but a fascinating country, and I think he is able to pick out the ironic, the bad, the good, the funny and the very sad. When I look through his work, I feel that nothing has really changed. There are still funerals; there are still the deserted bars and people gambling. His is a tough and deeply poetic vision that will always be relevant.

Mark Haworth-Booth on London 1951–2

Although I am not a serious photographer, two people always make me itch to pick up a camera. First, Henri Cartier-Bresson with his brilliance of timing, in which form, narrative and symbol merge in the famous ‘decisive moment’. Secondly, Robert Frank. He showed his mastery of this kind of photograph in his image of a little girl trotting down a London street past a hearse – and being dragged into it by every line in the picture. However, his gift is for something more naked and direct.

Frank loved photographing London’s city gents. This is a typical specimen. The uniform of black overcoat, black trousers and bowler distinguishes the pedestrian from those around him in their grey-toned clothes. He cuts a fine figure, a sharp silhouette, against his muted surroundings. This is the prevailing grey of the fog that creeps into all the corners of London in T.S. Eliot’s early poems. It is also the grey of the age of austerity and post-war smogs. Smog – a thick and sometimes deadly mixture of fog and coal smoke – is an even more distant verbal memory than other words and phrases of the time, such as bakelite and bomb-site. Frank constantly photographed the ‘peasouper’ smogs he found in London. His subject strolls purposefully through – I suppose – the City. (Did you know that the 25 bus route passes by the Bank of England and St Paul’s on its way from Victoria to Dagenham and was introduced on 3 May 1950?) He holds his hands behind his back and they in turn carry a walking stick and newspaper. Is there something just a little martial about the pose? Is he ex-services – as enormous numbers of people were, of course, in 1951–3? However, all of these things – including the flash of that white sock – are not why I really like this photograph. I like it because Frank has photographed someone walking along thinking or dreaming, musing in his own world. Musing, perhaps, reflecting, gossiping with himself, being conscious.

The street-strolling homme sensuel moyen arrived as a photographic subject in the 1880s. He and sometimes she was captured by the newly empowered street photographer, armed with fast gelatin dry plates and relatively inconspicuous small cameras with fast shutters and quick lenses. Robert Frank pictured modern people thinking in a variety of settings, including cars, cafés and lifts. Like his fellow Beats, he absorbed and used the existentialist ideas of the time. He was interested in capturing raw consciousness and he found a way to do it with a Leica camera. This is at the heart of the precious gift he gave to his successors, especially Garry Winogrand, Diane Arbus and William Eggleston.