Amedeo Modigliani painted the nude model throughout his career. Among the early examples are Nude with a Hat (recto; Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, Haifa; C7a), Nude Study (private collection; C8), Bust of a Young Girl (private collection; C10) and Seated Nude (private collection; C11), all of which date from 1908.1 A few years later, when the artist was focusing on sculpture, he painted a series of nude caryatid-like figures inspired by Egyptian, Greek and Cambodian art (C32–39).2 However, it is the large-format reclining and seated nudes painted between 1916 and 1919 that have arguably become Modigliani’s best-known works. According to Ambrogio Ceroni’s publication of 1970, these make up roughly a tenth of the artist’s production.3 This paper focuses on eight paintings of nudes made between 1916 and 1919, paying particular attention to Modigliani’s methods and materials and to the evolution of his style.

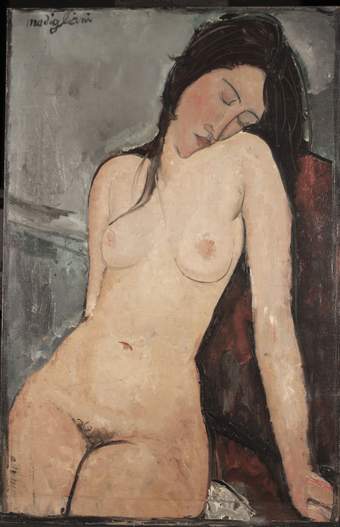

Fig.1

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude c.1916

Oil on canvas

920 x 600 mm

Courtauld Gallery, London

C127

Courtauld Department of Conservation

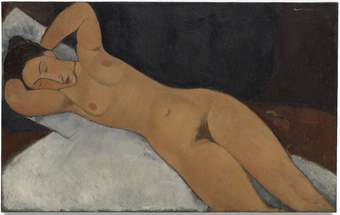

Fig.2

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude 1917

Oil on canvas

730 x 1167 mm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

C186

© 2021 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Fig.3

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude 1917

Oil on canvas

1140 x 740 mm

Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerp (KMSKA), Antwerp

C188

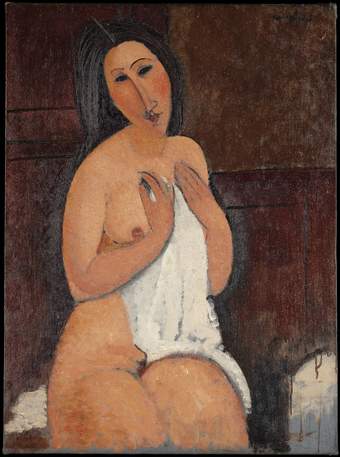

Fig.4

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude Reclining on a White Pillow c.1917

Oil on canvas

600 x 920 mm

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart

C196

Photo © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro

Fig.5

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude 1917

Oil on canvas

606 x 927 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

C199

Public domain

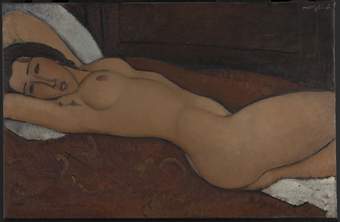

Fig.6

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (Nu assis à la chemise) 1917

Oil on canvas

920 x 675 mm

Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut (LaM)

C191

Public domain

Photo © C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.7

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude c.1919

Oil on canvas

724 x 1165 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

C200

© MoMA 2022

Fig.8

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude from the Back (Nu couché de dos) 1917

Oil on canvas

648 x 997 mm

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

C203

Public domain

Tate Modern’s exhibition devoted to Modigliani in 2017–18 brought together sixteen nudes, all of which were listed in the above-mentioned Ceroni publication.4 Five of these paintings have been the subject of detailed technical examinations and were described in an associated study published in the Burlington Magazine in 2018. These five were Female Nude c.1916, from the Courtauld Gallery, London (C127; fig.1); Nude 1917, from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (C186; fig.2); Seated Nude 1917, from the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerp (KMSKA; C188; fig.3); Female Nude Reclining on a White Pillow c.1917, from the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart (C196; fig.4); and Reclining Nude 1917 from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (C199; fig.5).5 This article expands the corpus of study to eight paintings, with the addition of Seated Nude with a Shirt (Nu assis à la chemise) 1917, from Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne d’art contemporain et d’art brut (LaM; C191; fig.6); Reclining Nude c.1919, from the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA; C200; fig.7); and Reclining Nude from the Back (Nu couché de dos) 1917 from the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia (C203; fig.8). Each painting was examined using technical imaging, including infrared and X-radiography, coupled with pigment analysis using cross-sections and handheld and macro-XRF.6 The study benefits from the broader context around Modigliani’s materials and technique that is provided by the other articles in this issue of Tate Papers and from research by colleagues in France.7

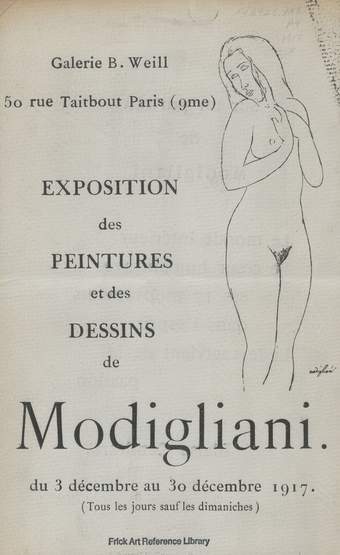

Fig.9a

Announcement for Modigliani’s solo exhibition at Galerie Berthe Weill, Paris, 1917

Frick Art Reference Library, Frick Collection, New York

Public domain

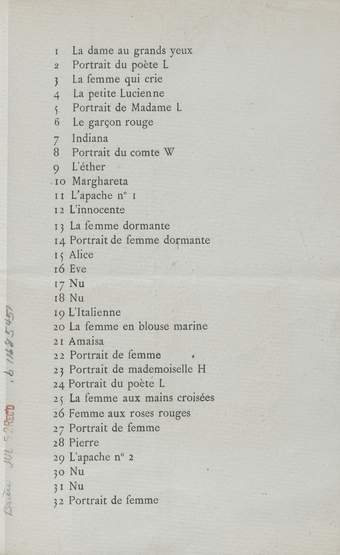

Fig.9b

List of works included in Modigliani’s solo exhibition at Galerie Berthe Weill, Paris, 1917

Frick Art Reference Library, Frick Collection, New York

Public domain

Modigliani’s nudes of 1917 are imposing in scale, frank in their depictions of women’s bodies, and free of decorative, narrative or mythological subtexts.8 Four were included in the artist’s only solo exhibition, which was held at Galerie Berthe Weill, Paris, in 1917 (figs.9a–b), triggering what became known as ‘le scandale’: Weill was forced to remove the nudes from the exhibition at the insistence of the local police.9 Modigliani sold just one drawing from the exhibition, but as Anna Zborowska, a member of the artist’s inner circle, noted in her memoirs: ‘if from the financial point of view the exhibition proved disappointing, the incident with the police achieved considerable notoriety’.10

Modigliani’s nudes are ‘real women’ of the First World War era, who were sensual, confident and depicted with natural body hair.11 The women were painted from life, portrayed as anonymous but distinct characters, with twisted torsos and provocative gazes. In most instances the artist captured specific personalities and characteristics. His friend, who also modelled for him, Lunia Czechowska, for instance, recalled how ‘before his model, Modigliani became completely different; he obsessively tried to capture her character in his work’.12 Only two of the nudes, Almaïsa 1916 (private collection; C131) and Standing Nude (Elvira) 1918 (Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern; C272), are named, while others indicate the sitter’s personality rather than their identity.

Modigliani in the studio: The artist at work

Over the course of his career, Modigliani had several studios in Paris – in rues de Douai, Ravignan, Joseph-Bara and de la Grand-Chaumière – and he created various makeshift studios in the hotels and houses he stayed at while sojourning in the South of France. Modigliani was not known to paint portraits or figure paintings en plein air (outside) or from photographs; the nudes were painted indoors from life.13

The backgrounds are loosely painted with gestural brushwork. This suggests that the artist may have invented the arabesques, curlicues and other flourishes that enliven the sitters’ settings, likely after his models’ poses were set in paint. Several of the nude paintings have a patterned red-ochre throw and white pillows which suggest a specific studio set-up, as in the Guggenheim, Staatsgalerie, Metropolitan and Barnes examples from the current study.14 The contrast between the brushy backgrounds and the precisely delineated outlines of figurative details distinguishes Modigliani’s paintings from those of his contemporaries, such as his friend Chaïm Soutine.

Supports: Formats, canvas and auxiliary supports

A technical examination of the supports for Modigliani’s nudes has allowed us to establish a pattern of use as well as an overall conclusion for the group of works included in this study. All of the nudes examined are painted on plain-weave canvas, which appears to have been the artist’s exclusive choice of support after 1916.

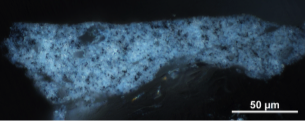

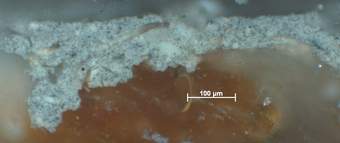

Fig.10a

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), micrograph showing the canvas composed of both thin cotton warp and thicker bast weft fibres

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Fig.10b

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), micrograph of the canvas showing thin cotton warps and broader jute wefts

Courtesy Denyse Montegut

Fig.10c

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), iPhone image taken with an APL-24 XMH macro lens showing a similar combination of fibres

© Isabelle Duvernois/MMA Paintings Conservation Department

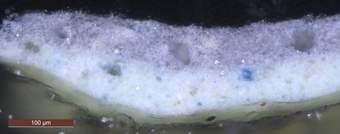

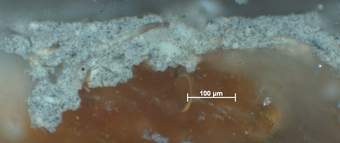

All eight canvases in this study were X-radiographed and studied as part of the Thread Count Automation Project (TCAP; see Table 1: Canvas and grounds).15 The thread counts can be used to compare canvas weave and weight, and identify similarities in canvas weaves. In the group of eight nudes, three canvas match groups, or cliques, were noted by the TCAP. The canvases from the Guggenheim (C186), LaM (C191), Staatsgalerie (C196) and Metropolitan (C199), in addition to the Barnes Foundation’s Boy in a Sailor Suit 1917 (C212), were found to have matching thread density patterns and formed a thread count and weave match clique.16 The supports in this group were identified as a plain weave mixed canvas made of cotton and bast fibres, both single-ply Z-twist (figs.10a–c).17 However, it was also found that the composition of the ground layers of the LaM and Barnes works differed from those of the Guggenheim, Staatsgalerie and Metropolitan nudes.

| Artwork | Thread count (vertical by horizonal) and weave match clique | Ground and priming layers (with cross-sections illustrated below the table) |

| Female Nude c.1916 Courtauld Gallery, London C127 |

11.2 by 13.6 threads per cm Clique 11 with C135 (Portrait of Manuel Humbert 1916; private collection) |

Layer 0: Thick layer of glue size. See fig.T1 below. |

| Nude 1917 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York C186 |

13.9 by 12.3 threads per cm Clique 2 with C191, C196, C199 and C212 (Boy in a Sailor Suit 1917; Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia) |

Layer 1: Bluish-grey ground: Coarse particles of barium sulphate, finely divided particles of barium sulphate and of a carbon-based black, and a few particles of Prussian blue (identified using Raman spectroscopy). See fig.T2 below. The second layer is not visible in this cross-section. |

| Seated Nude 1917 Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerp (KMSKA) C188 |

10.9 by 15.4 threads per cm No canvas weave match |

White, commercially prepared ground with white priming (identified through visual examination). |

| Seated Nude with a Shirt (Nu assis à la chemise) 1917 Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne d’art contemporain et d’art brut (LaM), Lille C191 |

12.5 by 14.4 threads per cm Clique 2 with C186, 196, C199 and C212 |

Layer 0: Layer of glue size. See fig.T3 below. |

| Female Nude Reclining on a White Pillow c.1917 Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart C196 |

14.1 by 12.5 threads per cm Clique 2 with C186, C191, C199 and C212 |

Layer 1: Bluish-grey ground: barium sulphate, zinc oxide, lead white and a carbon-based black (identified using SEM-EDX). See fig.T4 below. |

| Reclining Nude 1917 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York C199 |

12.5 by 14.4 threads per cm Clique 2 with C186, C191, C196 and C212 |

Layer 1: Bluish-grey ground: barium sulphate and a carbon-based black; some gypsum (identified using Raman spectroscopy). See fig.T5 below. |

| Reclining Nude c.1919 Museum of Modern Art, New York C200 |

23.2 by 23.6 threads per cm No canvas weave match |

Layer 1: White, commercially prepared ground: lead white and barium sulphate (identified using XRF and Raman spectroscopy). See fig.T6 below. |

|

Reclining Nude from the Back 1917 |

24.1 by 22.0 threads per cm Clique 8 with C316 (Young Woman of the People 1918; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles) |

Layer 1: White, commercially prepared ground: the presence of lead white, iron-containing pigments and a barium-based compound, such as barium sulphate, was inferred from XRF. FTIR revealed the presence of lead white, kaolinite clay and gypsum. Given that FTIR is a microanalytical technique, it is likely that barium sulphate is also present based on the larger area. Analysed using XRF. See fig.T7 below. |

Table 1: Canvas and grounds

Details and analysis of the thread counts, weave match cliques, and ground and priming layers of the eight paintings analysed in this study

Fig.T1

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), photomicrograph of a cross-section showing glue size, a pale blue-green ground layer and an upper bluish-grey ground layer

Aviva Burnstock

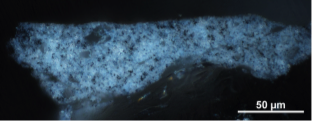

Fig.T2

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), sample cross-section showing the ground preparation photographed under visible illumination; original magnification: 200x

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Scientific Research

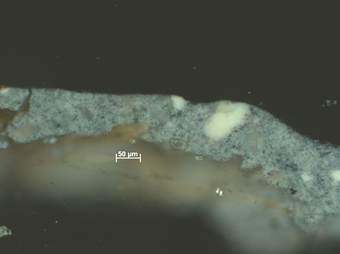

Fig.T3

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), photomicrograph of a cross-section showing a single ground layer with glue sizing

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Fig.T4

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude Reclining on a White Pillow (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart), photomicrograph of a cross-section showing a bluish-grey ground layer

Aviva Burnstock

Fig.T5

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), sample cross-section showing the ground preparation photographed under visible illumination; original magnification 200x

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Departments of Paintings Conservation and of Scientific Research

Fig.T6

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), photomicrograph of a cross-section in visible light showing the white ground layer

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Fig.T7

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude from the Back (Barnes Foundation), photomicrograph of a cross-section in visible light showing the white ground layer

© Scientific Analysis of Fine Art, LLC and Barnes Foundation

Fig.11

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail showing the exposed ground layer and absence of paint at the lower centre edge of the canvas

© MoMA Conservation 2022

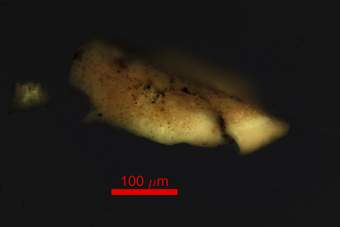

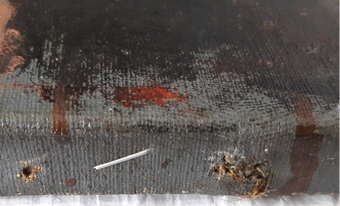

Fig.12

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail showing the tacking margins with two red paint drips

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Fig.13

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail showing a drip of fluid paint extending from the face of the painting onto the tacking margin, and pooling along the edge

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Modigliani also often painted with his pre-stretched canvas on an easel, which is evidenced by voids of paint in the lower front edge where the lip of the easel shielded the canvas from the paint (see, for instance, the MoMA Reclining Nude; fig.11). However, some evidence may point to the absence of an easel, suggesting he may occasionally have worked on a canvas tacked to a solid support.18 Red paint drips that continue onto the bottom tacking edge of Seated Nude with a Shirt may suggest that the painting was first painted unstretched (fig.12). MoMA’s Reclining Nude also shows drips along the bottom tacking edge, but it was painted on an easel (fig.13). The Metropolitan’s Reclining Nude shows red paint drips along both the bottom and right tacking edges.

As an artist of little means in his early career, Modigliani was known to reuse canvases, particularly before 1916.19 In two nudes from 1908, Nude Study and Bust of a Young Girl, there is evidence to the naked eye of an underlying inverted female figure’s head to the right of the sitters, although it is not clear whether these are by the artist’s hand.20 In both works, Modigliani barely covered the underlying compositions using a dilute blue-black layer of paint.

Modigliani made consistent use of commercially prepared canvases. In this respect and others, Modigliani’s nudes are in line with the rest of his production from 1916–19. He used a narrow range of standard canvas sizes and formats. Of the forty nude paintings listed in Ceroni’s publication of 1970, marine format canvases are most prevalent. Ten were painted on no.30 marine and nine on no.40 marine canvases. In general, Modigliani preferred marine canvases used in a horizontal orientation for his reclining nudes, while he would use them in a vertical orientation for seated portraits. An exception in this group is Seated Nude with a Shirt, which was painted on a no.30 paysage bas canvas.21 Whether the size of the works was dictated by Modigliani’s decision to use standard sizes of strainers or stretchers or by the image he wished to paint remains unclear. The artist’s choice of canvas weight varied in the late 1910s. For example, the canvas of the Antwerp Seated Nude is more coarsely woven than those of the MoMA Reclining Nude and Reclining Nude from the Back (see Table 1: Canvas and grounds).

Fig.14a

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), visible light image of the original strainer construction showing the four nails at the top right corner joint

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

Fig.14b

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), X-radiograph of the original strainer construction showing the four nails at the top right corner joint

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

The Courtauld, Antwerp, Lille and Metropolitan nudes retained their original strainers, while others, including the Guggenheim, MoMA and Barnes nudes, were mounted onto new stretchers during the lining process, thus eliminating the evidence of whether a strainer was used (see Table 2: Stretcher sizes and formats). The Courtauld and Metropolitan nudes have five-membered no.30 marine format strainers, with the Metropolitan canvas used in a horizontal orientation. The original strainers are joined using four nails at each corner joint, which was a common construction method during the early twentieth century (figs.14a–b).22

| Artwork | Dimensions (height by width) and format | Observations |

| Female Nude c.1916 Courtauld Gallery, London C127 |

92 by 60 cm (rotated) No.30 marine basse (62.1 by 92 cm) |

Original |

| Nude 1917 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York C186 |

73 by 116.7 cm (rotated) No.50 marine haute (116 by 73 cm) |

Not original (replacement) |

| Seated Nude 1917 Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerp (KMSKA) C188 |

114 by 74 cm No.50 marine haute (116 by 73 cm) |

Original Six-member strainer (non-keyable) with horizontal and vertical half-lapped crossmembers; four nails at each corner joint |

| Seated Nude with a Shirt (Nu assis à la chemise) 1917 Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne d’art contemporain et d’art brut (LaM), Lille C191 |

114 by 74 cm No.50 marine haute (116 by 73 cm) |

Original |

| Female Nude Reclining on a White Pillow c.1917 Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart C196 |

60.6 by 92.7 cm No.30 marine basse (62.1 by 92 cm) |

No observations |

| Reclining Nude 1917 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York C199 |

60.6 by 92.7 cm No.30 marine basse (62.1 by 92 cm) |

Original |

| Reclining Nude c.1919 Museum of Modern Art, New York C200 |

72.4 by 116.5 cm (rotated) No.50 marine haute (116 by 73 cm) |

Not original (replacement) |

|

Reclining Nude from the Back 1917 |

64.8 by 99.7 cm (rotated) No.40 marine haute (100 by 65 cm) |

Not original (replacement) |

Table 2: Stretcher sizes and formats

Details of the sizes and formats of the stretchers used for the eight paintings analysed in this study

Ground layers

Modigliani’s choice of ground colours changed over his career. His early works show a preference for coloured preparatory layers, whether artist applied or commercially prepared, whereas after 1918 almost all of his works were composed on white primed canvases. In our study of this group of eight nudes, we noted the use of a bluish-grey ground in the earlier works and white ground layers in the later works. This suggests that in his mature works, Modigliani shifted his preference from the use of a bluish-grey ground to a light-reflecting white ground, which imbued his increasingly thin paint layers with a distinct luminosity.

Fig.15a

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), cross-section showing the bottom layer of the painting’s two-layer ground

© Department of Scientific Research, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Fig.15b

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), cross-section showing the one-layer ground with glue sizing

Fig.15c

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), cross-section showing the one-layer ground

© Departments of Scientific Research and of Paintings Conservation, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A bluish-grey ground layer in a variety of tones was found on five of the nudes in this study: the Courtauld, Guggenheim, LaM, Staatsgalerie and Metropolitan canvases, all of which date from 1916–17. For the Courtauld’s Female Nude, the open weave canvas was first prepared with a thick layer of glue size followed by a pale blue-green paint, over which a bluish-grey upper ground layer (composed primarily of a mixture of white and finely divided black pigments) was applied (see Table 1: Canvas and grounds).23 The canvases used for the LaM, Staatsgalerie and Metropolitan nudes were prepared with a single layer of a bluish-grey ground, but their compositions differ. The Guggenheim painting has an additional blue priming layer that the artist applied in large swathes over the first bluish-grey ground layer. According to the TCAP, the Guggenheim, LaM and Metropolitan nudes are executed on canvas that comes from the same canvas bolt. However, the fact that the ground compositions are different raises questions about the preparation of the canvas – that is, whether it was commercially or artist-prepared (figs.15a–c).

A single white commercially applied ground layer was noted on the canvases of the Antwerp, Barnes and MoMA nudes. The grounds of the Guggenheim and Antwerp paintings have an additional priming layer applied over the commercial layer (see Table 1: Canvas and grounds).

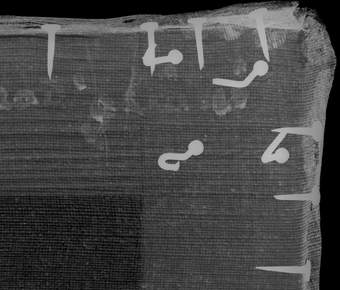

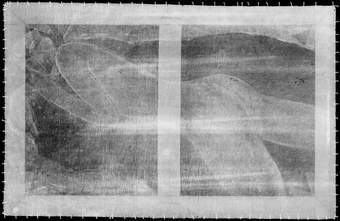

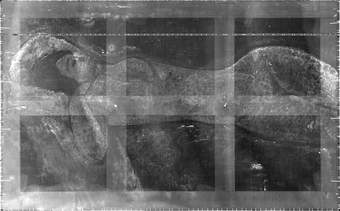

Fig.16

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude from the Back (Barnes Foundation), overall X-radiograph composite

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Fig.17

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), X-radiograph showing a series of curved vertical bands that may be related to the commercial priming process, in which long spatulas were typically used to apply the ground layers

© MoMA Conservation 2022

The X-radiograph of the Barnes’s Reclining Nude from the Back reveals a radio-opaque horizontal pattern that appears as wide sweeping strokes across the canvas (fig.16). This pattern indicates that the ground layer was applied with a large spatula-like tool, and it appears on other canvases, including the MoMA nude (fig.17).24 Although this may indicate that the same firm prepared the canvas, it is possible that the application technique was common among various firms at that time.

Underdrawing and underpainting

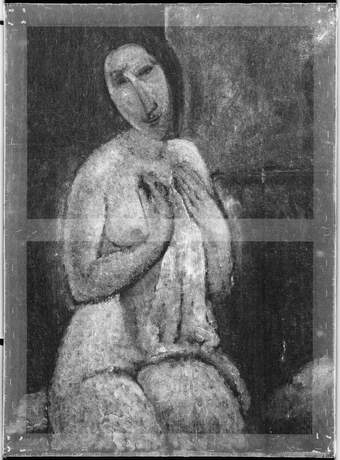

Fig.18

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude from the Back (Barnes Foundation), infrared reflectogram with red lines added to indicate the underdrawing

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Reclining Nude from the Back has a graphite underdrawing visible through the thinly applied paint. Infrared reflectography provided further information and shows that Modigliani began the painting with quickly applied gestural marks that established the slope of the model’s back, positioned the legs, arms and hands on the canvas, and minimally marked the figure’s facial features (fig.18).25 The underdrawing indicates that the bend of the proper left arm was first positioned further away from the model’s body; the arm was ultimately brought closer to the torso in later painting stages. The underdrawing also indicates that changes to the hairline and chin were made as the painting progressed, with the hairline raised and the chin lengthened in later paint layers. The form of the nude was then sketched with fine dilute black painted lines, followed by further reiteration of the contours in black and ochre tones as the painting progressed.

Infrared images of the Courtauld, Guggenheim, LaM, Metropolitan and MoMA nudes do not show any clearly distinguishable underdrawing in a dry medium, such as graphite pencil or charcoal.26 The artist did, however, use a fine brush to draw the form and composition of the nudes in dilute black or blue-black paint on the canvas before applying colour. This method of drawing directly on the canvas with paint aligns with Léopold Survage’s recollections of his friend Modigliani: ‘He would begin by tracing his drawing with a very fine brush, in much the same way as he drew his famous pencil sketches, sometimes controlled or sensitive, sometimes violent and harsh, depending on the character of the sitting model and the way he felt about him or her’.27 Seated Nude with a Shirt appears to have neither an underdrawing nor a sketch in dilute black paint.

Reserve and outlines

Fig.19

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), detail illustrating the use of reserve as an outline

Courtauld Department of Conservation

Modigliani used two distinctive and complementary effects to reinforce the contours of forms in his nudes: bare reserved areas and coloured outlines. In the Courtauld, Guggenheim, LaM and Staatsgalerie nudes, patches of the reserve (areas of exposed bluish-grey ground) appear around the contours of the figures (see, for example, fig.19). The areas of reserve create shadow in or around the skin tones, while the blue-grey tone of the ground accentuates the vibrancy of the pink-orange flesh.

Fig.20a

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail showing the bluish-grey ground layer left in reserve around the shape of the face and mainly around the nose and the eyes

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.20b

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail showing the bluish-grey ground layer left in reserve around the left thigh and white shirt

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

In Seated Nude with a Shirt, large areas of unpainted coloured ground are used to create volume and describe features, such as in the left thigh and around the arms and nose (figs.20a–b). This could suggest that Modigliani had a clear sense of his composition before he began work and deliberately used a dark ground layer to make the white fabric of the shirt appear brighter. A use of complementary tones – juxtapositions of the blue-grey ground with the peach and rosy colours of the flesh – is also evident in the Guggenheim’s Nude, where the artist similarly left blue-grey priming visible to describe the contours of the face, facial features, pubic area and armpits.

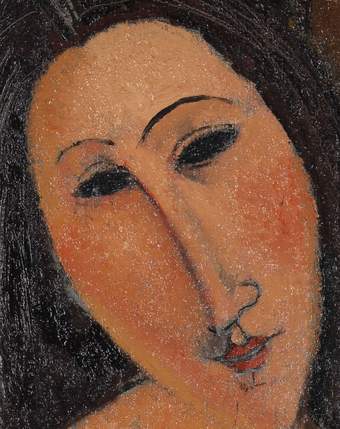

Fig.21

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude (KMSKA), detail of the lips illustrating the use of a blue-grey tone over the line of the nose

In the Seated Nude from Antwerp, Modigliani applied a bluish-grey paint that mimicked the tone of the ground over the flesh colours, in order to strengthen the profile of the model’s nose (fig.21).28 More radically, in the Courtauld’s Female Nude, Modigliani applied the blue background paint over the still-wet paint of the model’s right arm in order to alter the pose. The change removed the distraction of the arm from the contrast of waist and hip, drawing further attention to the pelvis.

Fluid outlines, drawn with a thin brush in black, blue, brown, and red and yellow ochres, are often visible at the contours of Modigliani’s figures. The outlining of figures in the Courtauld, Guggenheim, LaM, Metropolitan, MoMA and Barnes nudes ranges from thin strokes to a wider, impasto reinforcement of the contour. This thicker build-up of paint at the perimeter of the figure is clearly visible on the surface and in X-radiographs. In the Barnes’s Reclining Nude from the Back, a textured background evolves around the thinly painted torso. A thick brushstroke of a blue-black colour follows the long, sloping curve of the model’s back while a thin ochre yellow tone outlines the lower leg and buttocks. Thinly applied black paint delineates the lower edge of the red cloth and mixes wet-in-wet with the ochre sofa. Dabs of an impasto blue-green paint were applied with a splayed brush, following the upper contour of the red cloth and creating a border to the complementary cool-toned background. A similar technique was used to define the inner edge of the model’s raised arm in the MoMA nude: a limb slimmed at its outer edge by a dark brown outline.

Brushstrokes and smoothing of texture

Fig.22

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), X-radiograph showing dabbed and splayed brushwork

Courtauld Department of Conservation

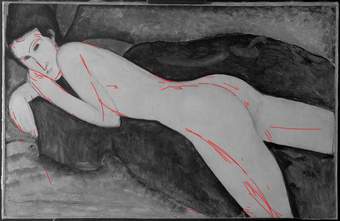

Fig.23

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), overall X-radiograph composite showing the smooth and textured brushstrokes

© C2RMF / Jean-Louis Bellec

Fig.24

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), overall X-radiograph composite with stretcher bars digitally removed

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

The application of fan-shaped marks made with a splayed brush, together with a sequential dabbing application, formed the first stage in Modigliani’s nude paintings in several examples in this study. These brushmarks are often visible on surface examination and were typically used to describe a model’s body, as seen in the examples from the Courtauld and Antwerp, where raking light images and X-radiographs emphasise these characteristic brushstrokes (fig.22). In Seated Nude with a Shirt, smooth brushstrokes are used for the face and the upper body, while the legs are painted with large textured brushstrokes that create an illusion of volume (fig.23). The Metropolitan’s Reclining Nude is consistently textured across the figure’s face and body. The X-radiograph reveals Modigliani’s bristle brush application as well as the polished areas of the breast, the buttocks and the thigh (fig.24).

Fig.25a

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), the sitter’s face photographed in raking light

© 2021 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Fig.25b

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), the sitter’s face photographed in raking light

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

The paint layer in the Metropolitan and Guggenheim nudes is generally pastose, medium rich, with numerous gritty fibrous inclusions. The faces are no exception and raking light photography illustrates the textural quality of the artist’s modelling (figs.25a–b). Modigliani was perhaps adapting his sculpting skills into two-dimensional modelling conventions: the flesh appears to sit thickly on the surface, with evidence of spatula application, polishing, scraping and blending.

Fig.26

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), photomicrograph showing the polishing striation pattern and fibre inclusions in the breast area

© Isabelle Duvernois / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

Fig.27

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail in raking light showing blotting, smoothing and polishing in the model’s upper chest

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Fig.28

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), X-radiograph showing the build-up of paint at the edges of the forms

Guggenheim Conservation Department

The initial splayed brushstrokes of the Courtauld nude were followed by the application of more flesh paint. Before the final layer of flesh paint was dry, the surface was smoothed to a velvety, even texture, characterised by small lumps of dragged semi-dry paint. Smoothing of the painted surface was also noted on the Antwerp, Guggenheim and Metropolitan nudes. Many fibre inclusions in the flesh tones of the Metropolitan nude suggest that Modigliani used a cloth to polish the paint surface to its present buffed appearance (fig.26). Modigliani’s daughter Jeanne – although she could not have seen her father at work – related that ‘sometimes he spread a sheet of paper over the fresh paint in order to obtain a better blending of his colours’.29 The artist’s move away from the rapid rendering visible in the earlier Courtauld Female Nude might indicate that he aspired to a higher level of surface finish. He used the smoothing technique most often in his larger-scale nudes, such as the MoMA canvas (fig.27). In the Guggenheim picture, short rapid brushstrokes describe the bedclothes, arms, and legs, while the face, breast and some areas of the torso and abdomen have been smoothed or polished; the raised forearm of the figure also displays Modigliani’s characteristic splayed brushwork. In the X-radiographs of the MoMA and Guggenheim nudes there is considerable paint build-up at the edges of the forms (figs.17 and 28).

Fig.29

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail showing the black outline of the figure

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

In all the paintings analysed in this study, Modigliani reiterated and adjusted the outline of forms using black, deep red, blue or brown paint. The outlines of the Guggenheim figure are apparent beneath the upper application of flesh paint, where thick brushwork often stops just short of the contours. Modigliani reinforced the line in black, blue and brown after he painted the flesh. The reiteration of outlines using black paint is also evident in the later nude from MoMA, where the dark contours emphasise the border between the figure and the background. The same is observed in Seated Nude with a Shirt (fig.29).

Facial features

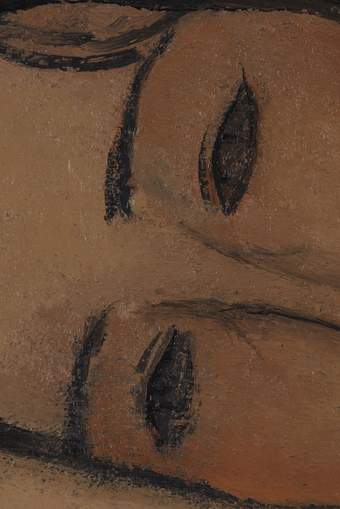

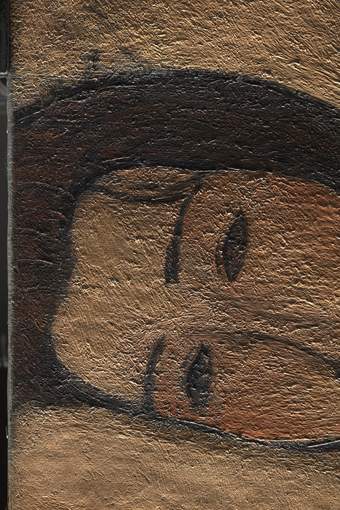

Fig.30

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail showing the outline of the bridge of the nose blending into the background colour, and the closed eye without eyelashes

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Modigliani carefully articulated the facial features of the models, often using a thin brush and black paint. In areas of the MoMA nude, for example, this outline bled and partially blended into the surrounding paint (fig.30). The faces of the Guggenheim and LaM nudes are mask-like, with the paint brushed in a uniform direction. This treatment recalls Modigliani’s sculptures of heads, inspired in part by his observation of African masks and by Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), which Modigliani must have seen at the Salon d’Antin in Paris in 1916.30 The faces of some of the other nudes included in this study, however, appear fairly coarsely painted, with visible brushstrokes, roughly blended passages of colour and black painted outlines on top of the paint layer. This is especially true of the Metropolitan’s Reclining Nude.

Fig.31a

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail of the proper right eye

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Fig.31b

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), detail of the eyes and eyelashes

Courtauld Department of Conservation

Fig.31c

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), detail of the eyes and eyelashes

Courtauld Department of Conservation

Fig.31d

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), detail of the eyes

© 2021 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Fig.31e

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail of the eyes

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.31f

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail of the proper right eye

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.31g

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail of the proper left eye

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.31h

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail of the eyes

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

Fig.31i

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude from the Back (Barnes Foundation), detail of the proper right eye and the profile of the nose

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

There is significant variation in the depiction of features such as the eyes and lips. In the MoMA nude, the model’s proper right eye is closed and delineated with a dark, crescent-shaped line (see fig.31a). This is also true of the Courtauld nude, but there the eyelashes are defined with wet-in-wet brushstrokes, the black picking up the wet flesh colour beneath (figs.31b–c). Both eyes are closed in the Guggenheim painting, defined by two curved black lines plus a few short strokes for the eyelashes. The sockets were left in reserve, and the eyelashes were defined before the thickly rendered lids were painted (fig.31d). The eyes of the LaM’s Seated Nude with a Shirt are painted directly on the bluish-grey ground layer, as open pools of black with the merest hint of eyelashes, made with flicks of the brush using the wet black paint from the edges of the eye (figs.31e–g). The eyes of the Metropolitan nude, gazing directly at the viewer, were painted wet-in-wet on top of the flesh tones, with quick thin strokes of black and blue paints that blend with one another, resulting in a brownish grey colour (fig.31h). The eyes of Reclining Nude from the Back were left in reserve as Modigliani first applied a layer of flesh colour to the face (fig.31i). A thin line of dilute black paint roughly outlined the shape of the eye, which was then filled in with a cool grey tone. The reserve for the right eye forms a continuous line with the reserve left to indicate the profile of the nose.

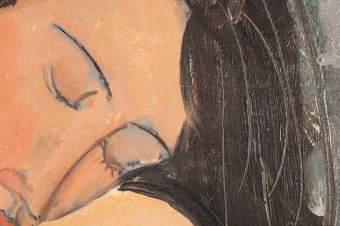

Fig.32a

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), detail of the lips

Courtauld Department of Conservation

Fig.32b

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail of the lips

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.32c

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), detail of the lips

© 2021 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Fig.32d

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude from the Back (Barnes Foundation), detail of the lips

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Fig.32e

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail of the lips

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Fig.32f

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail of the lips and teeth

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

Modigliani’s treatment of lips varied according to the model. The lips of the Courtauld nude were outlined in black paint over bluish-grey priming. The flesh-coloured paint was applied up to the edges of the mouth, and the lip colour was applied in two strokes of red (fig.32a). For Seated Nude and Female Nude Reclining on a White Pillow, the lips were painted wet-in-wet, in two shades of red, over a reserve of bluish-grey reinforced with black outlines (see fig.21). The lips of Seated Nude with a Shirt were also executed directly on the bluish-grey ground layer, using vermilion mixed with lead white and a red-based pigment for the highlight (fig.32b). Here too, black outlines further define the shape of the lips.31 It can be seen beneath the contours of the vermilion lips of the Guggenheim nude that they were painted in reserve (fig.32c). A thin ochre base colour and some black outlines are in evidence. After the lips were painted, they were delineated with more emphatic black lines, followed by final flesh tones that were applied up to and around the lips with a dry scumble.

The shape of the lips in Reclining Nude from the Back is delineated by a fine line of dilute black paint on the white ground layer (fig.32d). Red vermilion paint fills in the outlines, with a deeper red tone applied on the upper lip and to indicate a shadow on the lower lip.32 Thin black lines further define the shape of the lips; a pale flesh colour between the lower lip and chin creates a sense of volume. In the MoMA nude, the model’s sealed lips are set in profile with fine black lines (fig.32e). They are painted with the same rosy hue that highlights the figure’s eyelid and cheekbone. The mouth of the Metropolitan’s nude, while sharing many of the pictorial features described above, is somewhat atypical in this group (fig.32f). Here, the model’s white teeth are visible through her parted lips.

The amount of modelling and shaping around the lips varies, sometimes with deep grey shadows emphasising the contours of the nostrils and philtrum. Modigliani often deployed two or more red tones to differentiate the upper and lower lips, and varied the order in which he applied flesh colour and red and black contours. He often left the lips in reserve and painted the red tone into the gap. Finally, he added black outlines. In some cases, touches of flesh paint overlap the black contours to refine the final shape.

Body features

Fig.33a

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), detail of the pubic hair

© 2021 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Fig.33b

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art),

detail of the pubic hair

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Fig.33c

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail of the underarm hair

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Fig.33d

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), detail of the pubic hair

Courtauld Department of Conservation

Fig.33e

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail of the pubic hair

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

However stylised, Modigliani’s nudes depict individualised women with distinctive attributes. These include body hair, which Modigliani represented in several different ways. In the Guggenheim nude, the bluish-grey priming is left in reserve in the underarm and pubic areas. Brown paint is smoothly applied and allows the ground to show through (fig.33a). A similar treatment of the pubic area can be seen the Staatsgalerie nude, where the artist feathered soft brown paint over the bluish-grey ground layer that was left in reserve. In the later MoMA nude, however, he painted the pubic hair over the flesh (fig.33b); the underarm hair is depicted in burnt umber partly mixed in with flesh-tone paint (fig.33c). Only the Courtauld nude’s pubic hair is curly (fig.33d). The pubic hair on the LaM nude is executed both directly onto the ground layer and onto the skin; in this work, two lines in the same black and brown pigments used for the hair define the lower border of the white drapery (fig.33e).

Fig.34a

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), detail of the right breast

Courtauld Department of Conservation

Fig.34b

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), detail of the right breast

© 2021 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Fig.34c

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail of the breasts

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Fig.34d

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude (KMSKA), detail of the breasts and nipples

Fig.34e

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail of the breast

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.34f

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail of the breasts

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

Modigliani’s depiction of breasts varies. The nipples of the Courtauld nude are depicted with dashes of transparent red over roughly applied and still wet flesh paint (fig.34a). The Guggenheim nude’s breasts were left in reserve, and the lighter pink nipple was painted over a darker ochre layer, with the surrounding flesh tones painted up to the nipple and smoothed (fig.34b). In contrast, the MoMA figure has one breast subtly outlined in grey and light brown, while the breast in profile is set against the darker outline of the background (fig.34c). The orange-pink paint describing the nipples was lightly applied after the underlying creamy pink paint had dried. In the Antwerp Seated Nude, one nipple is in profile and the other is outlined in black (fig.34d). Both are thickly painted and textured. The nipple of Seated Nude with a Shirt is defined by the bluish-grey ground layer left in reserve between the flesh of the breast and the nipple (fig.34e). The areola is simply painted with a wet-in-wet combination of red and reddish brown; a dash of a pale flesh colour suggests the nipple. In the breasts of the Metropolitan nude, the medium-rich pastose paint layer has been polished and smoothed by the artist, presumably using a rag, to achieve a smooth finish (fig.34f).

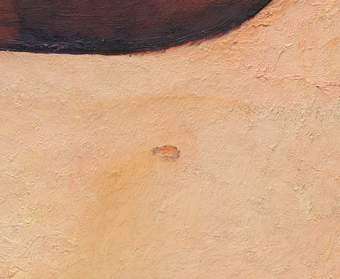

Fig.35

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), detail of the navel

Courtauld Department of Conservation

Fig.36

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail showing the three layers of paint applied to create the navel: a brownish-red underpaint with an almond-shaped outline that was partially rubbed over with the surrounding flesh tone and then highlighted with a daub of orange-pink paint

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Fig.37

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Museum of Modern Art), detail of the forearm showing modelling of the arm using smooth and impastoed stippled brushwork side by side with subtle modelling and highlighting daubs

© MoMA Conservation 2022

Other features including navels are depicted in various ways, either by a few deft strokes of pink paint (as in the Courtauld nude; fig.35), or by layering brown, warm white and pink paint (as in the MoMA painting; fig.36). A variety of brushwork is visible on the forearm of the MoMA Reclining Nude, including stippling and blended strokes used together to create volume (fig.37).

As described above, Modigliani’s painted nudes employ a variety of brushwork, from pencil-thin fine lines to bravura brushwork applied with a staccato zigzag and a wide brush. To emphasise contours, he would often stipple impasto paint with the tip of the brush. Other areas show evidence of polishing or smoothing.

Scraping, incising and tool marks

Fig.38a

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail of the hair

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.38b

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail showing incised lines in the hair

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.38c

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), detail showing incised lines in the hair

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.39

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), detail in raking light showing scoring lines in the hair

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

Fig.40

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), detail of scraped lines in the wet paint of the hair

Courtauld Department of Conservation

Modigliani often incised lines into thick paint and used distinctive, swirling brushstrokes to create effects of light and shadow in his paintings, suggesting a possible affinity with his approach to sculpture. Prior to dedicating himself to painting from 1914, Modigliani spent at least two years working on sculptural heads and figures. In several of these, such as Head 1911–12 (CXVI) from the Minneapolis Institute of Art and Head of a Woman c.1911–12 (CXVII) from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Modigliani carved lines into the top of the head to indicate hair. In his paintings, however, the gesture is more descriptive and less decorative. In Seated Nude with a Shirt, for example, a series of strongly incised lines that reach beyond the contours of the head indicate the central parting and texture of the model’s hair (figs.38a–c). Scoring lines can also be seen in the hair of the Metropolitan Reclining Nude (fig.39). Modigliani conveys hair texture in the Courtauld Female Nude with deep incisions into the wet paint (fig.40), likely made with a tool such as the end of a brush handle or the tip of a painting knife.

The nudes painted before Modigliani moved to the South of France in 1918 are in general more thickly painted and have significant surface texture. In these works, there is evidence of scraping into wet paint to create a smooth texture, or sometimes to create or emphasise a line. Both techniques can be seen in the Guggenheim nude, where semi-dry oil paint has been scraped into the facial features to smooth the texture, as well as into the hair to create lines indicating hair strands. Similarly, in Nude on a Divan 1918 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; C145), a deep incision separates the model’s arm from her breast.33 The technique of working the wet paint with the end of the paint brush or other tool is not present in the MoMA nude except for some small, randomly positioned, and likely accidental diagonal tool marks that appear along the lower edge.34 A reductive technique was used by Modigliani to create the decorative pattern on the red cloth on Reclining Nude from the Back. Modigliani painted the red cloth in multiple layers to achieve the rich burgundy colour, with warm yellow decorations. The shape and tone of the red cloth were loosely laid in with a red lake (alizarin crimson) that allowed the white ground layer to show through. Over the first layer of colour, the artist applied a deeper tone created by mixing a red lake with bone or ivory black, resulting in a multi-layered burgundy tone.35 Using a painting knife to scrape the still-wet second layer, Modigliani revealed the underlying layer, thus creating the swirling forms of the decoration, which were then brushed in with a broad stroke of ochre paint.36

Changes and modifications

Fig.41

Amedeo Modigliani

Female Nude (Courtauld Gallery), detail showing adjustments to the position of the hip and arm

Courtauld Department of Conservation

Fig.42a

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), X-radiograph detail showing the change in the eye placement

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

Fig.42b

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude (Metropolitan Museum of Art), normal light detail photograph of the face

© Evan Read / MMA Paintings Conservation Department

Technical images of certain nudes in our study show that positional adjustments were made to the figures. These include the outline of the hip and arm in the Courtauld picture (fig.41); the facial features of the Metropolitan nude, where the figure’s eyes, nose and mouth were repositioned lower on the face, perhaps to prevent too radical a cropping of the top of her head (figs.42a–b); and a change in position of the left arm and leg in the Guggenheim painting. The model in the MoMA nude cradles her head in her left arm. Here Modigliani also slightly extended the shape of the head by extending the brown hair where it meets the wrist and fingers of the model’s upraised arm. Slight modifications to the outline of the burgundy red cloth were made as the artist was working on the Barnes nude, and a change to the position of the proper right arm was made between the underdrawing and painting stages. Modigliani also lengthened the face of the model by extending the chin and forehead height in the paint stage as compared to the underdrawing.

Pigments and suppliers

Modigliani obtained supplies from vendors near his studios on the rue de la Grande-Chaumière and the rue Joseph-Bara. Anna Zborowska recalls: ‘How many times did one have to run to Madame Castelucho[?]’, referring to Diane Castelucho, a nearby colour merchant in the rue de la Grande-Chaumière.37 Other suppliers the artist used included Hardy-Alan, Didot-Bottin, Pascal et Coccoz and Dupré et Cie.38 Historian Pascal Labreuche suggests that the artist bought supplies from Sennelier at 3 quai Voltaire; Lefebvre-Foinet also listed him as a client.39

Fig.43

Amedeo Modigliani

Seated Nude with a Shirt (LaM), composite image of elemental distribution maps obtained by MA-XRF showing lead (Pb), zinc (Zn), barium (Ba), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe) and mercury (Hg)

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

For the nudes, Modigliani used a limited range of tube oil paints containing the following pigments: lead white, zinc white, vermilion, red lake(s) (including alizarin crimson in the Barnes red cloth), iron-containing pigments including sienna, ochres and umber, Prussian blue, synthetic ultramarine, cobalt blue, Naples yellow, bone or ivory black and viridian or another chromium-containing green.40 A narrower pigment choice was identified in the Guggenheim and Metropolitan nudes, including ochres, bone or ivory black, vermilion and red lake(s). A 1981 study of Modigliani’s pigments by Susy Delbourgo and Lola Faillant-Dumas also identified chromium yellow or cadmium yellow, which were noted in the MoMA and Barnes paintings.41 The pigments on the MoMA nude were identified as vermilion, cadmium yellow, cadmium red, red ochres, synthetic ultramarine and bone or ivory black; the green paints contain a mixture of Prussian blue and chrome yellow, and possibly a chrome green.42 Pigments identified in the Guggenheim nude by portable XRF included lead white, zinc white, vermilion, iron earths (sienna, ochre), with the assumed presence of ivory or carbon black and possible red lakes. Modigliani used a highly restricted palette for Seated Nude with a Shirt: lead white, barium sulphate, a zinc-based pigment, bone black, iron-based pigment(s) (presumably red ochres and/or umbers), vermilion, red lake and calcium sulphate (fig.43). It is interesting to see how Modigliani anticipated the position of the white shirt, which he painted directly onto the ground layer, rather than layering it over the skin tones. This suggests that he had a clear vision of the composition before he started painting (see the iron and mercury elemental maps in fig.43), as noted by Barbara Buckley and others.43

Fig.44a

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude from the Back (Barnes Foundation), elemental distribution map obtained by MA-XRF showing zinc (Zn)

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

Fig.44b

Amedeo Modigliani

Reclining Nude from the Back (Barnes Foundation), elemental distribution map obtained by MA-XRF showing mercury (Hg)

© 2022 Barnes Foundation

There is a wide range of flesh tones in the nudes. Modigliani captured his models’ skin tones by varying the amount of white in mixtures, using a limited palette. There is some consistency in his combinations of pigments for flesh, including a mixture of white with vermilion and a separate application of a transparent red lake. Unlike the other paintings in this group, Modigliani used zinc white mixed with chrome orange and vermilion for painting the flesh of Reclining Nude from the Back (figs.44a–b).44 Vermilion was also used for the lips, some shading on the face, and in some areas of the red cloth.45 For Seated Nude with a Shirt, the white used for the flesh tones is exclusively lead white. Zinc/barium areas visible in the elemental distribution maps (fig.43) do not correspond to the paint layers but to the ground layer left in reserve. Details such as the brighter pinks highlighting the figure’s breasts in the MoMA nude were sometimes added after underlying paint was dry.

Surface and varnish

All the nudes examined have been varnished (most probably as part of conservation treatments) and remain so except for the Guggenheim and MoMA pictures, which are now displayed unvarnished after recent treatments.46 The original intention of the artist in relation to the surface finish of his nudes is not known. The artist Ludwig Meidner references Modigliani’s early practice of applying ‘as many as ten layers of varnish’ to his finished works to mimic the ‘pellucid, iridescent’ effect of old master paintings,47 but it seems that this may not apply to the later nudes. The conservation history of the Courtauld’s Female Nude provides evidence that Modigliani displayed these works unvarnished, and thus may not have varnished them himself. In 1959, before it was lined, Female Nude was documented in a photograph that shows an unvarnished strip at the lower edge of the work. The application of a varnish changes the saturation of the paint, particularly in the darker passages. This, together with the artist’s concern for the surface finish of his nudes, might be worth considering in relation to the future conservation and display of these paintings.

Conclusion

This technical study of nudes painted by Modigliani between 1916 and 1919 reveals affinities between many of his works in the genre. They are largely composed of similar materials and are painted using comparable techniques, although in combinations that are far from prescriptive. The fact that they are made on supports of relatively good quality is indicative of the artist’s changing fortunes. The use of commercially primed canvas cut from the same roll, or bolt, provides evidence that links three of the nudes: the Guggenheim’s Nude, Seated Nude with a Shirt from the LaM, and the Metropolitan’s Reclining Nude, works that are also similar in the handling and application of paint.

It was only in the Barnes’s Reclining Nude from the Back that a graphite underdrawing was noted. More usually, the artist worked directly onto the canvas in paint, making compositional changes as he progressed. Although the range of pigments used for the paint of nudes in this study was fairly consistent and limited, visual examination and XRF studies of Reclining Nude from the Back and MoMA’s Reclining Nude suggests that this changed in the artist’s last years in the South of France, when his range of paints expanded to include some extra pigments, including zinc white, bright chrome-based greens, chrome yellow-orange, and cadmium yellows and reds.

The Courtauld’s Female Nude represents the first stage in the development of Modigliani’s most celebrated group of nudes. Modigliani used a distinctive splayed-brush application to create a stippled effect of impastoed paint for skin tones. The warm flesh tones were often set against a complementary bluish-grey ground, a technique that is visible in the Guggenheim, LaM and Metropolitan paintings, which were made between 1916 and 1918. The Seated Nude from KMSKA in Antwerp, with its white ground and selective applications of a bluish-grey tone, provides a link between the nudes painted on bluish-grey grounds and Modigliani’s later nudes on white grounds, such as the MoMA and Barnes examples.

Although some characteristics appear consistently in the works studied here – such as the use of scraping and an interest in colour contrast – an evolution in Modigliani’s approach to the nude is nonetheless apparent. When he returned to the theme of the nude in 1919, after having spent a period in the South of France, he no longer used thick, heavily worked paint to describe flesh. Instead, with growing confidence and in line with the broader interest in colour and light that emerges in his late works, he created luminous bodies that almost dazzle in their brightness. It would be interesting to extend this study in the future to consider some of the last nudes that he made, such as those in two private collections and the Galleria Nazionale d’arte Moderna in Rome (all titled Lying Nude and painted in 1919; C323, C324 and C325).

Modigliani’s concentration on the nude during the war years may reaffirm the role that his dealer Léopold Zborowski played in Modigliani’s artistic development and choice of subjects. As we know, the dealer not only paid for the models, but also provided safe spaces for him to paint in Paris and the South of France, and procured the necessary materials. With Zborowski’s continued support Modigliani produced an impressive oeuvre that remains deserving of further scholarly research.