To think of the world of Amos Tutuola, its borders and routes, pathways and detours, is, in the first place, to engage with an impulse both radical and simplistic. Here was a self-confessed uneducated man who wrote his first book to pass time. His grammar was deficient, even by his standards. When asked by the writer Femi Osofisan, in an interview three years before his death, ‘How do you feel about using the English language for your stories?’, Tutuola replied:

That gives me a lot of problem, but I don’t bother much about that. I always have Yoruba/English dictionary, which I look at when I want to use language in English … I open it, and then find the English, which I will use for the story. So that helps me a lot. In fact, I have much problem when I am writing in English.1

Yet, resolving to serve as a translator – or more aptly, an interlocutor – of fables, he established for himself a reputation that made his technical skills as a writer of little consequence. There is perhaps no other Nigerian writer published in his day – and as I wonder about it, no prominent Nigerian writer being published today – whose work has reflected this distinctive balance.

The Tutuola project still generates controversy. Broadly speaking, there are, then as now, two responses to his work. The first accepts his genius on the basis of his outlandish narratives, the incomparable range of his imagination – he is a virtuoso of magical realism in Nigerian fiction. The second is skeptical of his genius, squarely because his education was limited, his stories merely stilted, even primitive, the kind that appealed to those who fawned over the exotic. Both responses have always seemed to me, dare I suggest, beside the point. In my reading, the premise underlying Tutuola’s work is its relationship to colonial time. Indeed, all artists of his generation, regardless of the genre in which they worked, had to answer for their relationship to the past, and what could be said of their ever-evolving identity. They were haunted by the nightmare of a modern era they had been thrust into.

How did his work stand in relation to his time? That time is contemporaneous, in the sense that he exists in and out of the century of his life. In the sense that to make a distinction between what could be called ‘tradition’ in his work – drawn from Yoruba mythology, at least superficially – and what could be called ‘the new’ – that is, a recording of oral narratives – seems pitilessly insufficient to cater for his mastery of the transitions through worlds of colonial and non-colonial time. Each return to his work and the impulse for it required a suspension of all that is known about linear, durational time. You step into the circular time of consciousness.

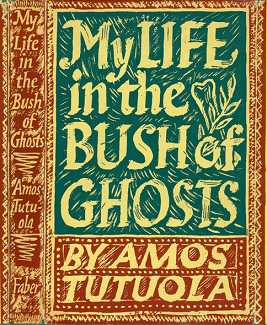

Fig.1

First edition cover of Amos Tutuola’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts 1954

© Faber & Faber

I am most interested in My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1954), his second novel, a lodestar for me in his constellation of tales about humans in a supernatural world (fig.1).2 A liberal reading would consider the work a travelogue, its episodes book-ended by departure and return. I recognise its themes as those associated with the experience of travel – a distinct sense of home, an awareness of being estranged, the peculiarity of encounters with strangers, and upon return, a feeling of nostalgia for the foreign land visited. To read the book is to encounter the feeling of estrangement. Put squarely, it is to encounter yourself as a stranger. In one sense you are the stranger who relates to the disorienting feeling of the protagonist, a human among non-humans. In another sense, you are the unnamed protagonist, travelling through a foreign land, constantly at the verge of despair. Suppose the book can be read in that way, the episodes are the dazzling flashpoints of years that elude enumeration. Indeed, the novel is not entirely without chronology; in the Bush of Ghosts he is old enough to get married and have a son. But since he entered the Bush ‘unnoticed’, too young to know that ‘it was a dreadful bush or it was banned to be entered into by any earthly person’, his travails take on the character of a wanderer who, to survive, must surrender to the unpredictable vagaries of the journey itself.

In one episode, he arrives with his wife at a Lost or Gain Valley. A slender stick enables travellers to walk over the deep valley, but it is so slender no one can walk on it with clothes on. Before crossing over, they have to take off their clothes. They arrive at the other side of the valley naked, hoping to pick up the clothes of those who have crossed in the opposite direction. Perhaps the clothes picked up are worse than those left on the other side, or perhaps they are better. This is why it is called the Lost or Gain Valley. Yet it is said that no stranger crosses the valley without a loss. All the ghosts and ghostesses of the area are very poor, wearing clothes made from animal skin. They survive by exchanging their wretched clothes for the expensive apparel of travellers.

It is especially because two worlds collide that the protagonist is outside durational time.

To make sense of the geopolitics of such time, it is necessary to make a supposition, open to debate as it might seem: an African writer, in the light of colonialism, acknowledges a shared history with European thought. Say the Reformation, which produced the kind of England that sent its emissaries abroad, versed in the complex entangling of Church and Empire. But where the Reformation was a movement by learned men to undercut their privileges and translate the Bible into the language of the common folk, colonialism excused its violence by asserting the lesser humanity of the native. In this sense, the education that was handed to students like Tutuola was impaired from the start by a sinister logic, which is not to say that nothing good can come out of being taught to speak and write in standard English. Following that logic I recognise the extent of Tutuola’s dilemma. The matter was civilisational. People in a great patch of territory were being taught to hybridise themselves, to hyphenate their identity, English-Yoruba for instance. Tutuola’s lifework is evidence of a gnarled transplant, to use a horrid metaphor. The central question becomes, what is undermined, or what is accentuated, by his use of non-standard English?

I take note of artist Uche Okeke’s 1971 book, Tales of Land of Death: Igbo Folk Tales.3 The book is punctuated intermittently with drawings by the author of the mythic protagonists of the folktales and riddles (drawings which could accompany a future edition of The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952) or My Life in the Bush of Ghosts). ‘These traditional Igbo tales’, Okeke writes in his introduction, ‘are told around the flickering dull yellow flame of an oil-palm or in a moonlit village square. The storyteller is a humorous and keen observer of life around him’. One such tale by Okeke could illuminate Tutuola’s obsession with the communal story. I render it in my own words:

A king once challenged anyone in his town to tell a story without end. The winner would be rewarded with food for the rest of their life. The news of the contest spread far and wide. Poets and singers feared it was a trick. Who could tell an endless story?

The day came and the square was crowded. In other circumstances it would be spectators gathered for a wrestling match. There were hundreds with stories, and if you began with a stutter you were jeered and booed, eliminated from the contest. Some would end their stories by repeating a song. Yet when the song became too long, the crowd shushed them.

A sluggard came to tell his tale, and was mocked by the crowd. The king, intrigued by his audacity, waved him on.

In another town, he began, there was a powerful ruler. He ordered his subjects to build a grain store with walls as high as the tallest iroko. For ten years his people toiled, but even then the great granary was not in sight. In the process workers died like fowls, but the work continued. After another ten years the granary was completed.

But the wicked king, unsatisfied, ordered that the great store should be filled to overflowing with grains of maize. This took more time than the construction. From season to season all laboured without rest. The king died without seeing the end of the task. But his son, the new king, was determined to extend the activity even after the granary had been filled.

And so he gave his pet bird the final task: fly to the granary, and each time return with a grain of maize.

The sluggard began to mimic the gestures of the relentless bird.

Flying up

Flying down

Taking a grain of maize.

The crowd roared, joined in.

They sang until the king, keeled over in fatigue, declared the sluggard the winner.

Tutuola was keen, and unabashed about his keenness, for folktales that held him in awe. His son, Yinka Tutuola, recounts in a 2013 interview how he collected stories:

Whenever he was on annual leave (before he retired from government work) he would travel to his village with an old Pye reel-to-reel tape recorder; we used to go with him if we are on holidays, and there he collected stories of all kinds. At nights in the village, he would buy palm wine to entertain his guests who would be competing to tell the best stories they could. He would record these stories still very late in the night.4

Prior to owning a recorder, he worked from memory. After the townspeople retired for the night, he sat up and wrote the stories as he remembered them. He was interested, as this evidence suggests, in something considerably larger than the story itself. Perhaps his entire enterprise as a storyteller was to place a finger on the pulse of narrative.

In that final interview with Osofisan, Tutuola’s answers are those of a man who has turned over several matters in his mind, and come to certain compromises. He makes a living as a farmer, and does not prefer writing to farming. ‘I have the same interest in both.’ He does not prefer one of his books to the other. ‘I put the same interest in them, because when I am writing, I am always happy.’ Why does he write? ‘I want people to enjoy what I do. That is what forces me.’ And why does he write in English? ‘I started to write my stories in English because we prefer English to our own language in those days.’5

He remained ‘the unlettered man of letters’, as literary historian Bernth Lindfors called him, until the end of his life, never returning to school.6 This could support the claim that, despite the fecundity of his imagined worlds, his work is of inferior literary standard. Since this debate has been attached to his name from the outset of his career, I am disinclined to have this essay read as an attempt to take either position (even if it might be clear that I favour his insistence on writing in non-standard English). In fact, it might be worthwhile to study the incomparable nature of that debate. No other Nigerian writer, I reiterate, has received wide attention with such basic credentials.

§

The story that prompted me to consider Amos Tutuola in new light is a minor flourish in the account of his search for a publisher. As far as I know no one but Lindfors – arguably the most important scholar on Tutuola’s early work – recounts it. This was in 1948, when Tutuola was recently married, and while he worked as a messenger in the Department of Labour in Lagos. ‘The Wild Hunter in the Bush of the Ghosts’, the manuscript in question, was written in collaboration with Edward Akinbiyi, Tutuola’s friend who worked at the same government department. The nature of their collaboration remains unclear – whether it was co-written, or dictated by one and recorded by the other – but Tutuola is confirmed as the one of the pair who wrote out the final draft. The story, which came to seventy-seven single-spaced foolscap pages, was offered to Focal Press in a query letter. Lindfors expands as follows:

The publisher he approached was … Focal Press, a publisher of technical books on photography. Tutuola, a keen amateur photographer who had set up a ‘photoservice’ in Ebute Metta with a view toward taking up photography ‘as a profession’, owned a number of books by this publisher and found their London editorial address in one of them. When he wrote, he asked if Focal Press would like to consider a manuscript about spirits in the Nigerian bush illustrated with photographs of the spirits! This was an offer no photography publisher could refuse. A. Krazna-Krausz, Director of Focal Press, noted in a letter (to Lindfors, in 1978) that, ‘what I was really intrigued by when inviting Tutuola to submit his work was his claim to be able to photograph ghosts’. When the manuscript, wrapped in brown paper, rolled up like a magazine, and bound with twine, arrived a few months later, there were sixteen photographic negatives accompanying it, most of which, when developed, turned out to be snapshots of hand-drawn sketches of spirits featured in the story. There was also one photograph of a human being. Tutuola had hired a schoolboy to draw the sketches and then had photographed what the boy had drawn.7

Tutuola’s decision to submit to the press could be interpreted as an indication of his desperation. That would be, as far as the story goes, right. Writers know that publishing a book with a traditional publisher is a combination of good fortune and importunity. In retrospect, however, Tutuola’s cold pitch to Focal Press reflected a relationship with photography that casts a veneer of modernism on that desperation.

When Lindfors interviewed Tutuola in July 1978, the writer mentioned that he indeed made a foray into photography, with the hopes of becoming a professional. How long this foray lasted is unclear, although I suspect that as interest in his writing grew, and benefits accrued, those hopes were eclipsed (there is evidence that after he was unable to continue his education, he tried his hands on several schemes).8 Had he become a photographer, what kind of photographs would he have made?

He claimed to be able to photograph ghosts. Let me suspend, for a few moments, the knowledge of how he substantiated his claim. Instead, I imagine myself in the position of the Director of Focal Press, enthused with, and curious about the claim to photograph ghosts. What would it mean, for a mind long versed in the rational, to imagine how ghosts might be pictured? What relationship do ghosts have with the camera?

As the story goes in Ben Okri’s The Famished Road, a photographer was taking pictures of a large group, and then portraits of certain individuals within the group.9 An odd explosion followed the camera’s flash. Stunned ghosts emerged from the light and melted at the photographer’s feet. For each picture the photographer took, five in all, the ghosts kept falling at his feet, still dazed by the flash. Fascinated by the camera, they climbed on him and clung to his arms and stood on his head. The photographer, who happened to be drunk, was not bothered to return to the studio, so he hung the camera on a nail in the house. The spirits encircled the camera. They kept pointing to it, talking in amazed voices.

If we were to believe Okri, and his literary progenitor Tutuola, ghosts would like to stand in front of the camera. Or to put it less directly, there is sufficient imagination to endow ethereal beings with corporeal qualities. The medium of photography is thus interlocutory, as if intercepting worlds seen and unseen.

Does Tutuola’s desperate pitch to the director of Focal Press trivialise his audacity to imagine photography as a medium placed at the service of conceit? No, it does not. Yes, his action was a gamble, and that manuscript never got published, at least in the form it was sent to Focal Press. Yet to live in Tutuola’s time (which is not simply the years of his life, 1920–1997, but equally all of Nigerian time, a time in which language for the future is constantly being hollowed out), is to resort to simple, audacious attempts to pitch forward. It is to take the language of the modern, including photography, and transform it into something sufficient enough to contain all the absurdities of African identity, if anything can be that large. It is to invent a strategy to break with the oral tradition while also consolidating it. Not to suggest that the ‘oral’ is always in need of consolidation in written form, but to ask: how is it possible that a once-colonised writer like Tutuola can use the colonial language in unheard-of ways? One possibility is to consider Tutuola, a primary school dropout, as a writer whose curriculum was colonised only in part, and how his lifework suggests a different lineage for Nigerian literature. What is the range of a literature that acknowledges The Palm-Wine Drinkard as an ancestral text, rather than, say, Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958)?10

A few years before his death, in response to Osofisan, who asked him, ‘What is your belief in life and death?’, he replied: ‘Let us put Christian religion apart. I believe that when one dies, that is not the end. He is still around. I believe that one who dies is still somewhere where we don’t know. But according to Yoruba belief, we say that, er, people who die have a town where they live together.’11 Let us put Christian religion apart? Decades earlier, in 1954, when he was interviewed for a profile in West Africa, Tutuola admitted to believing the tales he wrote, even if partly, regardless of his strong Christian views.12

The Christian afterlife is fundamentally dissimilar to the afterlife in Tutuola’s novels, the former endowing life after death with either punishment or reward, the latter endowing it with an eternal cycle of decision-making. In one you remain a protagonist, sinner or saint; in the other, whether in heaven or hell, you become an audience watching your immutable destiny unfold. I suspect that Tutuola did not feel beholden to reconcile these views (indeed the idea of reconciling disparate cosmologies is European, a worldview obsessed with the whole). To know in part was enough. The question was: what is the potential for the imagination? Is there anything sheerly unimaginable for the hand to depict, and the eye to see?

§

Postscript

Bea Gassmann de Sousa

A writer speaks of another writer. The contemporary literary author and art critic Emmanuel Iduma reflects on the legendary Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola, whose literary work also encompasses a rare archive of oral Yoruba folktales. Tutuola’s first novel was published in 1952, eight years prior to the declaration of Nigerian Independence. The self-taught writer’s efforts to seek a British publisher mirrors the experiences of many of his peers who were pioneers of Nigerian modernism before 1960. He was in many ways the opposite of his contemporary, the highly educated global traveller and celebrated artist Ben Enwonwu (1917–1994). Nonetheless, Tutuola shares with Enwonwu a similar bifurcation of identity as a condition of colonialism. This has not just become a topic in recent Western discussions about the legacy of modernism in Nigeria, but more importantly has become a point of discussion among a generation of contemporary Nigerian writers and artists who share a global platform. It is of immense importance to hear a contemporary Nigerian voice on the so often perplexing indeterminacies recent Nigerian cultural history yields. In this case, the most pertinent analysis of Tutuola stems from subjective experience and personal commentary. In empathising with another person we can sometimes seek a deeper truth than in the ‘infected’ historiography we lean on for factual certainties. History is not certainty, history is storytelling, so much is true for oral history. So why not tell a story about someone who tells a story? Amos Tutuola is key to the ways in which the oral history of Nigeria’s past finds its path into Western consciousness. Emmanuel Iduma tells a story about Tutuola’s passage and his legacy. Iduma’s story allows for a deeper understanding of the complexities of being in colonial times. He is a chronicler who wrestles Nigerian archival history from the colonial twists and interpretations, many of which stand uncontested as the only imprint of the past. In his 2017 photo essay titled ‘The Colonizer’s Archive is a Crooked Finger’, Iduma writes: ‘If colonialism breached the progressive time of the colonized, it also confirmed the suspicion that no time is unilinear. Imagine, then, a time bordered by a vicious colonial experience on one hand, and the uncertain future of an independent nation on another. I direct the affront of this essay at those whose lives unfold within those borders.’13 Amos Tutuola lived with those borders as a writer of novels and as a historiographer of an oral tradition. He was both an author and the embodiment of a collective voice. Emmanuel Iduma’s literary reflections on the possibilities and the origin of Tutuola’s narration pay credence to the work of a culture that retains an inherent social collectivity at its core. And beyond a deep-rooted sense of collective consciousness, which is not to be equated with nationalism, we always also find a reminder that Euro-modern unilinear teleology is not at the root of Nigerian temporality. The past is always in the living present in the words of the philosopher E.J. Alagoa: ‘Anya diálί bù ánya ekē: The eye of the man with local roots is (as penetrating as) the python’s eye’.14 This fundamental perception is omnipresent in Nigerian culture. Iduma summed it up when he began a presentation at Tate Modern in September 2017 with the words: ‘Nothing Wey Man Eye Never See’.15 All is there to be seen if only we allow ourselves to look.