Since the early eighteenth century France has been home to one of the finest portraits ever painted on British soil, a portrait of King Charles I by Sir Anthony Van Dyck (fig.1).1 Under the title Charles I at the Hunt c.1635 (or, in French, Le Roi à la chasse), it has been one of the jewels of the Louvre collection in Paris since the museum opened in 1793.2 The presence of this iconic work in the French national collection bears witness to the long-lasting prestige that Van Dyck enjoyed in France. Indeed, a high level of interest in his work was maintained in France from the artist’s death in 1641 to the end of the ancien régime, and he is frequently mentioned in the earliest works of art history from the second half of the seventeenth century onwards. This paper sketches a picture of Van Dyck’s reputation in France during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a subject that has been neglected by art historians, and that merits a fuller and more thorough investigation.3

Fig.1

Anthony Van Dyck

Charles I in the Hunting Field c.1635

Oil paint on canvas

2660 x 2070 mm

Musée du Louvre, Paris

© Cliché RMNGP – Musée du Louvre

Even before the artist’s death, French collectors took a keen interest in Van Dyck’s work. While it is true that Van Dyck never won royal commissions comparable to those of his master Peter-Paul Rubens, who was commissioned to decorate the Medici Gallery in the Palais du Luxembourg in Paris, he was among the small number of great foreign artists whom the French Crown commissioned from time to time. It is known from the early biographies – notably Giovanni Pietro Bellori’s Lives of Famous Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1672) and André Félibien’s Conversations on the Lives and Works of the Most Excellent Painters Ancient and Modern (1685) – that Van Dyck undertook at least two visits to Paris at the request of Louis XIII and his powerful minister Cardinal Richelieu. His last visit in 1641, the year of his death, is well documented. A letter from Van Dyck attests to the ‘esteem and honour’ shown to him by Richelieu,4 and, indeed, Cardinal Mazarin had Van Dyck in mind to paint a portrait of Richelieu, which he intended to serve as a model for a sculpted effigy of the prelate to be carved by Gianlorenzo Bernini in Rome.5 (Unfortunately, the letter in which Mazarin announced his intention to the sculptor was dated 18 December 1641, that is, after the death of the painter on 9 December.)6

Bellori and Félibien also record Van Dyck’s hope of winning important commissions from the French court, in particular, for the decorating of the Great Gallery of the Palais du Louvre, which in the end was entrusted to the French painter Nicolas Poussin.7 However, can the information provided by these two biographers be trusted? Félibien’s prejudice against the Flemish school and liking of Poussin is well known, and so his version of the story could be read as an assertion of the pre-eminence of Poussin and of the French school in general.8 Moreover, is it not plausible that the alleged ambition of Van Dyck may be an aspiration of the painter – or of his biographers – to rival the decoration of the Medici Gallery by Rubens? And that his failure to obtain the commission may be an early sign of the French public’s scepticism towards his ability to paint historical subjects? Such scepticism, as will be shown, recurs frequently in French critical assessments of the painter.

In spite of the esteem shown to him by Richelieu, the relationship between Van Dyck and the Court of France appears to have been one of missed opportunities. However, he did paint portraits of two high-ranking individuals close to the French court: the mother and the only brother of Louis XIII. Neither of these two works, however, was executed in France. The portrait of Marie de Médici, now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, was painted in Antwerp in the autumn of 1631, and that of Gaston d’Orléans, which is in the Musée Condé in Chantilly, was in all likelihood executed in the same city, in the spring of 1632.9 Both sitters had a delicate relationship with the court, as they had both been banished, but it is possible to suppose, given their high rank, that these portraits quickly became known throughout the kingdom of France.10 Indeed, the portrait of Marie de Médici entered the French royal collection in 1661.

A bizarre text by Georges de Scudéry – one of the most faithful writers of Richelieu’s circle – testifies to Van Dyck’s high status in the French court. Published in 1646, The Cabinet of Monsieur de Scudéry imagines an ideal gallery filled with the crowning glories of European painting. In this pantheon – which includes works by Cimabue, Antonello da Messina, Albrecht Dürer, Raphael, Titian and the Carracci brothers – Van Dyck is not forgotten. The artist is mentioned with reference to a portrait of the French Queen of England, Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I. Richelieu had at least one portrait of Henrietta Maria in his possession.11 It is not too much to suppose that the painting to which Scudéry refers is a work owned by Richelieu.12

Van Dyck was first and foremost appreciated in France as a portraitist of princes. Cardinal Mazarin, who was the greatest collector in France in the 1650s and one of the most powerful figures in the kingdom, avidly acquired paintings by Van Dyck. In all, he possessed twenty-four portraits of ‘persons of estate’ by Van Dyck – including the portrait of Marie de Médici, which passed into the collection of Louis XIV on his death – and one religious painting.13 The eminence of the portraits testifies to Mazarin’s assiduity, which is well documented. In late 1654, for example, Mazarin’s emissaries wrote to him from London about a diverse range of works by Van Dyck, including ‘a head of Van Dyck’s mistress, which is incomplete, thought to be one of his best works’.14 However, the discerning cardinal did not agree with the suggestion. He wanted more prestigious sitters in his collection, mostly from Van Dyck’s time in England, such as Charles I and Henrietta Maria, Lady Digby, and the Archbishop of Canterbury. The selection is indicative of the particular taste of the Cardinal, whose collection comprised the finest works by the Flemish painter in France at the time.

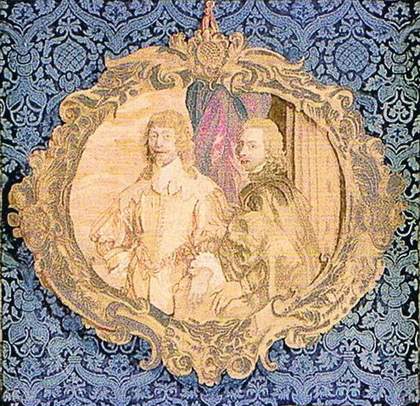

At the beginning of the 1670s, the collection of the young monarch Louis XIV was enriched with remarkable paintings by Van Dyck, as well as major paintings by Nicolas Poussin. Conversely, little real interest was shown towards work by Rubens. In 1671 the acquisition of banker Everhard Jabach’s collection brought ten paintings attributed to Van Dyck into the royal collection. They were for the most part religious pictures, including The Vision of Saint Anthony of Padua (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan) and Saint Sebastian After his Martyrdom (Musée du Louvre, Paris).15 There were also some ambitious portraits, including Prince Charles Louis, Elector Palatine and Prince Rupert, painted inEngland in 1637 (fig.2).16

Fig.2

Anthony Van Dyck

Prince Charles Louis, Elector Palatine and Prince Rupert 1637

Oil paint on canvas

1320 x 1520 mm

Musée du Louvre, Paris © Cliché RMNGP – Musée du Louvre

For close on two decades, paintings by Van Dyck regularly passed into the royal collection. In December 1681 the King visited his gallery in the Louvre and, according to a report in the Mercure Galant, singled out ‘fourteen by van Deick’, whereas Rubens is barely mentioned. As art historian Alain Roy has pointed out, Van Dyck seems to have been more appreciated at the French court than Rubens, owing to ‘his Flemish style for society people, tempered by Italianism and by the politeness of the Courts’.17 In 1683 the painter Charles Le Brun drew up the first inventory of the King’s collection of paintings, in which seventeen are attributed to Van Dyck.18 A little later, in 1685, the painter Gabriel Blanchard was commissioned to travel to Belgium, Holland and England to purchase paintings of the Northern schools on behalf of the King: ‘always works of “high taste”’, as Alain Roy noticed.19 On 13 May 1685 Blanchard acquired Van Dyck’s The Virgin and Child Adored by a Married Couple (Musée du Louvre, Paris) from ‘sieur Clerx’ (Sir Clerx), a banker, and some time between 1684 and 1706, Venus in the Forge of Vulcan (Musée du Louvre, Paris) entered the King’s collection.20 By the end of the seventeenth century, Louis XIV’s collection was exceptionally rich in works by Van Dyck, whose entire career was represented, with the exception of works from his youth and from his time spent in Italy (1621–7). There are several princely portraits, but the Crown did not show disdain towards portraits of individuals of more modest rank, nor towards great religious and historical paintings. This ensured that Van Dyck was far better represented than Rubens in the royal collection, placing him on a par with Poussin and Raphael.

The building of this remarkable Van Dyck collection coincided with a wave of recognition for the painter from several historians of Italian and French art. The first sizeable biography of Van Dyck was written by Bellori, whose Lives of Famous Painters, Sculptors and Architects was published in Rome in 1672, with a dedication to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s powerful minister. Van Dyck figures among the small number of non-Italian artists included in that pantheon of contemporary European art.21 The rise of Van Dyck’s reputation also coincided with the outbreak of a quarrel between advocates of ‘drawing’ and those of ‘colour’ in the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris.22 The Académie, founded in 1648, had been reformed by Colbert in the 1660s into an institution for the practical and theoretical training of artists, at which point members began to form opposing ranks, setting the beauty of drawing (identified with the intellectual value of art) against the brilliance of colour (more generally associated with the sensual characteristics of painting).23 Each side chose their idols and their champion. Raphael and Poussin were designated models of ‘drawing’, and the chronicler André Félibien champion. On the side of ‘colour’, Rubens was the uncontested model and the aesthetic theorist Roger de Piles his ardent defender. However, both camps took an interest in Van Dyck, although he was clearly identified as the pupil of Rubens, and each extolled his qualities differently, from more or less opposite ideological positions. Thus in 1685, Félibien, in his biography of Van Dyck, which was largely inspired by Bellori, enthuses that ‘his name will be famous for ever, for the excellent portraits he has left us’.24 Furthermore, in what might have been a tactical move bearing in mind Van Dyck’s training under Rubens, Félibien suggests that the artist transcended the sensuality of colour by constantly striving for distinction: ‘One may say that, apart from Titian, we have seen no painter go farther than he, in this genre of painting. His manner is noble, natural and easy.’25 However, the concession that Félibien makes to his adversaries on the side of colour is limited, for, according to him, Van Dyck was only superior in a minor genre, that of portraiture, whereas the entire French academic system was designed to extol the virtues of history painting. In that genre Van Dyck produced more delicate work than Rubens, yet, according to Félibien, due to his deficiency in the art of drawing, Van Dyck’s work is inferior to that of the supreme masters Raphael and Poussin.26 Félibien attributes this deficiency to the fact that Van Dyck painted quickly, ‘unchecked’, in the heat of his inspiration, and that this was to the detriment of drawing and composition.27 This argument is repeated in all the biographies of the painter by French writers, but, as this paper will show, a century later the artist’s characteristic speed was revised from being a cause of condemnation to proof of the high quality of his genius.

Thus Van Dyck becomes the paragon of the portraitist par excellence, not only for Félibien but for de Piles too. The artist’s ability to achieve life-like ‘resemblance’ by reproducing convincingly the features of his sitters is matched by his skill at capturing their ‘temperament’ or character, and flatter them if need be.28 In his biography of Van Dyck published in 1699, de Piles describes Van Dyck’s portraits as being ‘of a sublime order’, emphatic recognition of his distinction.29 By way of concession to the judgement of his rival Félibien, de Piles also recognises Van Dyck’s limits as a painter of history, but only to extol the qualities of Rubens, his master in that domain: ‘His [Van Dyck’s] compositions are ample and led by the same axioms as those of Rubens; but his inventions are not so sophisticated, nor so ingenious.’30 In his ‘Scale of Painters’, which comes at the end of his 1707 book The Principles of Painting, de Piles positions Van Dyck among the highest on the scale, close to, if not among, the greatest: Rubens first and foremost, followed by Raphael and Poussin.31

While flourishing in the pages of aesthetic discourse, Van Dyck’s work, in particular his British portraits, began to have a direct influence on pictorial production in France. This appears to have been most strongly felt between 1640 and 1660, and can be seen in portraits by Sébastien Bourdon, Charles Le Brun, Louis-Ferdinand Elle, and Charles and Henri Beaubrun. Bourdon’s The Man with Ribbons 1657–8 (Musée Fabre, Montpellier),32 for example, and the images of beautiful young women at the Château Bussin-Rabutin in Burgundy painted by Juste d’Egmont in the 1660s, recall Van Dyck’s double portraits of women painted in England in the 1630s such as Dorothy Viscountess of Berkshire with Elisabeth, Lady Thimbely (National Gallery, London).33 The influence of the Flemish painter can also be detected in portraits painted by Le Brun in the 1650s, such as the Portrait of Alphonse Dufesnoy (Musée du Louvre, Paris) and The Jabach Family 1657–60 (private collection).34 In the second half of the seventeenth century, while the greatest collections of the kingdom progressively acquired more and more of his work, many French painters, including Nicolas Loir, Jean-Baptiste Corneille and above all Antoine Coypel, Charles de la Fosse and Hyacinthe Rigaud, also began collecting works by Van Dyck.35 At the same time, Van Dyck’s paintings also became better known in the form of engravings, especially following the publication of Iconography of Van Dyck, a volume of engraved portraits.36

As well as Van Dyck, the Dutch portraitists Nicolas Maes and Caspar Nestcher also seem to have had an influence on painters in France, as can be detected in the portraits of Pierre Mignard, such as the Portrait of Mademoiselle de Blois c.1680 (Musée du Louvre, Paris).37 Indeed all the great portraitists of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries are indebted to the influence of Dutch and Flemish artists, from the disposition of the figures to the silky draperies caught in movement. However, the model of Van Dyck remains preponderant for the two great portraitists of the period: Hyacinthe Rigaud and Nicolas de Largillierre. Contemporaries of Rigaud certainly saw links between the French painter and the Flemish master. In his biography of Rigaud published in 1762, Antoine Joseph Dézallier d’Argenville regularly makes reference to Van Dyck; indeed, in the opening pages, where he writes about Rigaud’s death, he declares that ‘France has lost her Van Dyck in the person of Hyacinthe Rigaud’, and a little later, when he attempts to define the artist’s manner, he affirms that ‘the taste of Van Dyck has always been his object; rarely did he depart from it’.38 When Rigaud (who was of Catalan origin) moved to Paris, the young painter could not avoid studying the art of the Flemish master. Van Dyck’s works were well represented in the city’s royal collections, and his name was continuously brandished in the quarrel over drawing and colour. By the turn of the eighteenth century, Rigaud had become the quasi-official portraitist of the crowned heads of Europe, taking on the mantle of Van Dyck in that domain.39 Among the numerous examples of Rigaud’s sophisticated reworking of Van Dyck’s techniques, the early society portrait of Marie Cadenne 1684 (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen) demonstrates the French artist’s understanding and adaptation of Van Dyck’s portraits of British women, such as Mrs Endymion Porter (Syon House, Brentford) and Mary Hill, Lady Killgrew 1638 (Tate T07956), whom the Flemish artist presented as Venetian ‘beauties’. Moreover, it has been pointed out frequently that the composition of Rigaud’s most famous work, the Portrait of Louis XIV 1701 (fig.3), is identical to that of Charles I at the Hunt by Van Dyck.40 It is probable that the Van Dyck painting was in Paris at the end of the seventeenth century, although it has not yet been ascertained whether Rigaud had access to it. (The painting is known to have been in the Paris collection of the Countess of Verrue in 1736, although its location before that date is not known.) While it is true that the pose of Louis XIV, which is very choreographic, closely resembles other princely portraits of the seventeenth century, such as Louis-Ferdinand Elle’s Portrait of Louis XIV 1665 (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Metz), the correspondence between the kingly portrait by Rigaud and Van Dyck’s earlier painting is sufficiently striking to be worthy of note.

Fig.3

Hyacinthe Rigaud

Portrait of Louis XIV 1701

Oil paint on canvas

2770 x 1940 mm

Musée du Louvre, Paris

© Cliché RMNGP – Musée du Louvre

A comparison between the work of Van Dyck and that of Nicolas de Largillierre is even more revealing, for while Largillierre was also hailed by Dézallier d’Argenville as a ‘Van Dyck of France’, unlike Rigaud he had spent the first years of his career at the English court where he had the opportunity to study paintings by Van Dyck at first hand.41 Largillierre spent three periods in London: the first in as early as 1665–7, then again in 1675–9, then most likely in 1685.42 The influence of Van Dyck on his work seems to have been filtered through Peter Lely, who Largillierre met in London.43 The scenography, both natural and theatrical, of Largillierre’s Portrait of a Young Prince and his Tutor 1685 (National Gallery of Art, Washington) recalls the devices Van Dyck used in the British portraits of the 1630s, such as Self Portrait with Endymion Porter (Museo del Prado, Madrid), or the double portrait of Prince Charles Louis, Elector Palatine and Prince Rupert in the royal collection. In any case, comparisons with Van Dyck abound in the written assessments of Largillierre’s French contemporaries. For example, Dézallier d’Argenville compares the rapidity with which the two artists painted, writing at a time when a quickly executed painting was no longer seen in France as demonstrating a lack of attention, but rather as a sign of the vivacity of the artist’s inspiration.44

Between 1680 and 1720, Van Dyck’s history paintings, so underrated in France by Fébilien and de Piles, came to exercise influence on prominent French painters, especially Charles de la Fosse, who was close to the circle of the ‘colourists’. In 1689 la Fosse spent some time in London, where he was able to admire great history paintings by Van Dyck at first hand. La Fosse’s Venus Asking Arms from Vulcan for Aeneas (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes) has often been compared to Van Dyck’s painting of the same subject (Musée du Louvre, Paris), which was in the French royal collection at the end of the seventeenth century.45 Another great French history painter of the time, Antoine Coypel, who was to become first painter to the king, also drew inspiration for certain historical compositions from works by Van Dyck.46 For example, Coypel’s Democritus 1692 (Musée du Louvre, Paris), was inspired notably by the heads of the apostles by Van Dyck.47 Antoine Watteau, like his friend Charles de la Fosse, also had many opportunities to study the Flemish master’s work at first hand, in the collection of Pierre Crozat, Watteau’s wealthy patron in the second decade of the eighteenth century, and in London, where he visited in around 1719, towards the end of his life.48 Watteau’s Jupiter and Antiope (Musée du Louvre, Paris), which was probably painted in 1716 for the Duke of Arenberg, is a remarkable example of how Watteau appropriated compositions by Van Dyck, in this case his c.1620 painting of the same name (Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent).49

These examples demonstrate that French artists at the turn of the eighteenth century accorded greater significance to Van Dyck’s historical and religious paintings than did earlier artists, and that this moment represents the apogee of Van Dyck’s reputation in France. His works were superbly represented in the royal collection, abundantly and favourably commented upon in the artistic discourse of the time, and were a notable source of inspiration for a number of great living artists. It is therefore only to be expected that throughout the eighteenth century major works by Van Dyck were systematically acquired for all the great French collections, at a time when Paris was becoming one of the capitals of the European art market.50 Indeed works by Van Dyck were conspicuous in what was the most important art collection after that of the king, the collection of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, which was amassed at the beginning of the eighteenth century. In 1727 there were thirteen works in that collection attributed to Van Dyck, of which the majority were portraits, but there was also a religious painting.51 The collection was made freely accessible to artists and aesthetes, and served only to reinforce Van Dyck’s fame in France.52 The other major collections of the period were similarly rich with works by the Flemish master, including those of Crozat and Jeanne Baptiste d’Albert de Luynes, Countess of Verrue, who was known as the first great enthusiast in eighteenth-century France of Flemish painting.53 Indeed, it was in her drawing-room that Charles I at the Hunt was first displayed in France.54 A brief examination of the frequency with which works attributed to Van Dyck appeared in eighteenth-century sales catalogues confirms that his work was much sought-after in France.55 Indeed, his paintings could be found in the great Paris sales of the 1770s, including those of La Live de Jully (1770), Blondel de Gagny (1776), Randon de Boisset (1777), and the Prince de Conti (1777), and the prices obtained were often substantial.56 Among the considerable figures achieved by sales of paintings by Van Dyck in Paris at the time, the prices attained by Charles I at the Hunt and Portrait Said To Be of Ricardot upon entering the royal collection – 25,000 livres in 1775 and 14,820 livres in 1784 respectively – testify to the esteem in which the artist was held in eighteenth-century France.57

Van Dyck’s celebrity in Paris was further enhanced in 1750 with the inauguration of the ‘Cabinet du Luxembourg’, an exhibition gallery for the most distinguished paintings of the royal collection, housed in the Palais du Luxembourg. Van Dyck was represented there by three paintings: two great portraits of unidentified dignitaries and their children (Musée du Louvre, Paris) and the portrait of the Duke of Lennox (Musée du Louvre, Paris).58 During the reign of Louis XVI, the energetic Count d’Angiviller systematically acquired masterpieces to strengthen the royal collection in advance of the establishment of a grand museum in the Palais du Louvre. Unsurprisingly, works by Van Dyck were sought and purchased as part of this collection strategy. This is when the famous portrait of Charles I at the Hunt was acquired from the Countess of Barry in 1775, and the Portrait Said To Be of Ricardot, from the Randon de Boisset collection in 1784.59

In the middle of the eighteenth century, Van Dyck’s reputation was further strengthened by new publications favourable to Flemish art. In 1754 Jean-Baptiste Descamps published The Lives of Flemish and Dutch Painters, in which he gives pride of place to Van Dyck and establishes an impressive list of major works by the painter to be found in Paris collections of the time, citing close to fifty paintings.60 The publication of the book represented a turning point in the history of French taste for ‘Northern’ paintings. Thus, it is no coincidence that French painting of the 1750s and 1760s sees a blossoming of portraits ‘in the manner of Van Dyck’, an interpretation that was also applied to portraits produced in England at the same time.61 Indeed, this period also sees the French beginning to show more interest in artistic production from across the English Channel.62

During these years, several portraits presented at the Salon – the annual exhibition organised by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture – made explicit reference to British portraits by Van Dyck. At the Salon of 1759, for example, Jean-Baptiste Greuze presented ‘a portrait of Mademoiselle de Amici, in character dress’, which the critic of La Feuille nécessaire judged to be in the genre of Van Dyck.63 And at the Salon of 1767, Louis Michel Vanloo presented Boy Dressed in the Former Fashion of England (fig.4), a painting that drew the attention of the art critic Denis Diderot, who remarked: ‘The boy in full figure, dressed in the former fashion of England, is very beautiful in the drapery, in a true and natural pose … A fine piece quite in the manner of Van Dyck.’64 In the mid-eighteenth century, then, there emerged a type of portrait in which figures were dressed in early seventeenth-century costume, which contemporary commentators often regarded as paying homage to Van Dyck. This can only be a sign of the reputation of the Flemish master, and of the determination of portraitists to emulate his work in order to confer dignity on their own, despite the fact that portraiture was still judged to be an inferior genre by critics.

Fig.4

Louis Michel Vanloo

Boy Dressed in the Former Fashion of England 1767

Oil paint on canvas

1500 x 1080 mm

Courtesy Galerie Mendes, Paris

By the second half of the eighteenth century, virtuosity in painting became more highly valued, and the characteristic speed with which Van Dyck worked was hailed as exemplary of the artist’s genius. As early as 1754, the critic Jean-Baptiste Descamps, writing about Van Dyck’s painterly ingenuity insisted: ‘One cannot deny that he had the greatest facility ever known.’65 Van Dyck provided a model of a fine, freely sketched painting technique, in which paint was applied thickly and brush strokes were left visible. Writing in 1788, Claude-Henri Watelet summed up what eighteenth-century connoisseurs thought of quickly-sketched paintings: ‘The sketch is the first idea of the subject of a painting … The imagination is absolute mistress of the work and is impatient of the slightest slowing down in its production. This rapidity of execution is the principle of fire which gleams bright in the sketches of painters of genius.’66

In this context the speed with which Van Dyck worked was no longer considered to be a weakness but served as an example for contemporary painters. Thus in 1767, Diderot, commenting upon a small painting representing ‘Chaste Joseph’ by Louis Lagrenée, found fault in the artist’s free but uninspired technique: ‘There would still be much to say about this manner of execution. It is heavy, thick, delightful; but will there ever emerge a strong idea from it? An effect comparable to the brush of Rubens? Of Van Dyck?’67

Jean-Honoré Fragonard is one of the most famous French painters of the eighteenth century to have practised such a free, highly sketched technique. In 1773, an ironic pamphlet hostile to this kind of painting was published under the title Dialogues on Painting. It enthroned ‘divine Frago’ as absolute master, the ne plus ultra of ‘the brash, the rough and ready, the lashed-on-thick’, remarking that he possessed ‘the most capital brush, according to the chiefs of French painting’.68 Fragonard much appreciated and copied Van Dyck throughout his career, especially his portraits and history paintings, which he saw in Paris collections and in the course of his travels in Italy and in Flanders.69 In the contemporary critical literature on Fragonard, commentators often establish links between his imaginative heads, notably the heads of old men, with ‘the manner of Van Dyck’, and occasionally with ‘the manner of Rembrandt’.70

Towards the end of the 1760s Fragonard painted, in circumstances which remain unclear, a series of portrait busts of ‘figures of fantasy’.71 The sitters are dressed in costumes that were described at the time as ‘in the Spanish style’, but which were in fact very close to Flemish costumes of the years 1610–30, with round-pleated ruffs, high ruffles, short capes, voluminous slashed sleeves and opulent gilded chains across the chest – costumes that resemble very closely those worn by figures in French and English paintings ‘in the manner of Van Dyck’ from the 1750s and 1760s. Art historians have been able to determine that many of these ‘figures of fantasy’ are likely to be portraits of eminent individuals whom Fragonard may well have known from artistic circles, such as the dancer Marie-Madeleine Guimard, the critic Denis Diderot, or the Abbé Saint-Non, a connoisseur and patron of Fragonard, or from the most refined social circles, such as François-Henri, Duke of Harcourt.72 This highly personal repertoire of Paris celebrities from the years 1760–70 can in part be compared to the most famous collection of engravings after paintings by Van Dyck, the Iconography of Van Dyck, which was frequently re-editioned throughout the eighteenth century, and which brought together portraits of numerous personalities from the artistic, cultural and political spheres of the first decades of the seventeenth century.73 It has been speculated that Fragonard intended the series to be displayed in a gallery of portraits in his own apartment, although the fact that some of the paintings were sold off separately at the end of the 1770s casts doubt over this theory.74 It is known, however, that during the 1760s Fragonard was planning several initiatives that he intended would lead to engravings being made for the purposes of illustration, namely for books, most of which were abandoned.75 Was the ‘figures of fantasy’ series a similar initiative, intended to be published as a collection of engravings of illustrious and fashionable individuals along the lines of the Iconography of Van Dyck? While there is no documentary evidence to support this, it is clear that Fragonard borrowed from Van Dyck the idea of producing a collection of portraits of eminent personalities from diverse social backgrounds. Moreover, the type of costumes, the supple, dynamic poses of the figures, and above all the framing of the upper body seen from a low angle, all point to Van Dyck’s portraits as a source of inspiration. Indeed a comparison can be made between, for example, the portrait of the Abbé Saint-Non 1769 (fig.5), ‘painted by Fragonard in1769 in one hour’ according to a hand-written note on the back of the canvas, and the engraved portraits of Jan Snellinck (with the head thrown back and the position of the chest) or Gaspard de Crayer (with the ruff, the garments and the arrangement of the hands) by Van Dyck.76 Similarly, the portrait of the Duke of Harcourt by Fragonard (private collection) adopts the same haughty pose as the engraver Paul Pontius portrayed by Van Dyck, only in reverse.

Fig.5

Jean-Honoré Fragonard

Portrait of the Abbé Saint-Non 1769

Oil paint on canvas

800 x 650 mm

Musée du Louvre, Paris © Cliché RMNGP – Musée du Louvre

Although it received no publicity at the time, Fragonard’s series marked the culmination of the mid-eighteenth-century vogue for portraits ‘in the manner of Van Dyck’, representing the ultimate evolution of the ‘unchecked’ technique, the ‘free-flowing brushstroke full of fire’.77 From the mid-1770s this style of painting fell out of favour with the critics and was even subject to virulent attacks. While Van Dyck’s reputation remained pre-eminent, the vivacity of his painting no longer served as a model for French artists to follow.

When the new art museum housed in the Palais du Louvre in Paris opened its doors to the public after the fall of the French monarchy in August 1793, Van Dyck was reserved pride of place. He was represented by a total of six paintings: four portraits, which were his most celebrated works in France, one religious picture and one mythological painting.78 At that particular moment in time, however, it was not opportune to display the portrait of Charles I, which had come from the collection of an erstwhile favourite of Louis XV, the Countess du Barry. Following a major reorganisation of the museum, a new catalogue of the collection was published in 1799 that gave considerable importance to Van Dyck, with a larger selection of twenty-one paintings.79 Few artists were represented by that many works,80 and by the beginning of the nineteenth century Van Dyck’s position in the French pantheon of the greatest masters of European painting had been secured.

The inauguration of the Musée du Louvre marked the culmination of a long and rich tradition in France that recognised the exemplary quality of Van Dyck’s work. The museum’s collection provided a model for other national galleries to follow, cementing Van Dyck’s reputation in Europe. Whether he was appreciated for the dignity of his portraits or the more sensual spontaneity of his painting techniques, Van Dyck had always remained highly prized by the French public. He had been extolled as a paragon and a hero by oppositional factions of the Académie, combining apparently irreconcilable traits. It was no doubt for that reason that he was able to sustain for so long the interest of French scholars, collectors and artists, retaining to this day an eminent position in the collection of the Louvre.