‘Set or raised aloft, high up’; ‘Rising to a great height, lofty, towering’; ‘Exalted’; ‘Supreme’: by dictionary definition, ‘sublime’ signifies a state of elevation through which ascent towards physical or metaphorical heights brings about transcendence.1

‘Go, fell the timber of yon’ lofty grove’, the poet Alexander Pope (1688–1744) had the Greek author Homer say in The Odyssey, ‘And form a Raft, and build the rising ship, / Sublime to bear thee o’er the gloomy deep’.2

Yet, as these lines suggest, ‘sublime’ (etymologically perhaps sub limen, up to a high threshold) always carries with it – even if only as trace memory – that over which it climbs or floats: ‘the gloomy deep’.

Pope quickly turned to this alternative site or state of ‘sub’ to which sublimity is umbilically attached but from which it had to be distinguished if transcendent achievement, poetic or otherwise, was to remain clear in an increasingly competitive world. He therefore set about defining this realm which lay beneath the sublime’s aerial firmament, a realm which reaches down into the depths and which is characterised by both dazzling material riches and mysterious profundities: ‘The Sublime of Nature is the Sky, the Sun, Moon, Stars, &c. The Profound of Nature is Gold, Pearls, precious Stones, and the Treasures of the Deep, which are [as] inestimable as unknown.’ In Pope’s satirical account (his tongue was firmly in his cheek here), these depths are the imaginary province to which the second-rate artist seeking wealth and patronage aspires, the decidedly sub par counterpart to those exalted heights of poetic sublimity at which their more talented and judicious colleagues arrive. Mediocre writers and painters therefore practise (Pope argued) an ‘Art of Sinking’, a descent into that jarring mixture of obscure nonsense and trivial or gaudy allusions which nevertheless seemed to represent poetic depth to the pretentious. By ‘keeping under Water’, the artist could therefore achieve precisely that over which the sublime soared: ‘the Bottom’ of his art.3

This is a wholesale revision of the ancient Greek term ‘bathos’, whose original reference to ‘depth’ remains in the technical terms for deep-sea diving equipment, the ocean bed and its measurement yet whose rhetorical formulation by Pope – as a ‘ludicrous descent from the elevated to the commonplace … anticlimax’ – is now dominant.4

Seeking to consolidate an opposition between high and low, Pope’s ‘bathos’ is shot through with its divisive social implications, which find form in the fictive poetic examples – among them the lady who acts like a street hawker and the footman who speaks like a prince – with which he illustrates his account.5

By engaging with the implications of ‘beneath’, of the sub- in the sublime, this article sets out to challenge any sense of the sublime as necessarily already ascendant, as always and easily cut free from its murky remnant. In particular, this article will focus on the ways in which J.M.W. Turner set about suggesting, to an extent which is unprecedented in the visual representation of water, what it might be to be beneath – beneath the horizon, beneath the water and beneath paint. The broader implications of this ‘submarine’ state for the forms of subjectivity at stake in Turner’s work will be hinted at towards the end but, by way of instructive analogy, I want to begin with a metropolitan site which was all but given over in the early nineteenth century to the idea that paintings and people speak from the deep, in a process which seemed to conjure both the sublime and the subliminal.

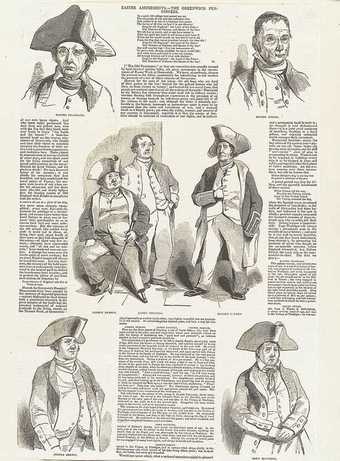

Fig.1

Easter Amusements – The Greenwich Pensioners … (with biographical details on each)

The Illustrated London News 13 April 1844, p.233

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

A living museum, Greenwich had become (within a few decades of the battle of Trafalgar) the ‘resting place’ of ‘national prowess on the … ocean’, an entire pantheon to a now-past greatness whose human and cultural fragments were placed on conspicuous display in order that ‘a commercial world’ be reminded of its moral debts.6 For the architects of nineteenth-century Greenwich’s transformation, all members of London’s cultural élite, those debts were – it should be understood by the site’s visitors – owed to the political status quo, to the charismatic leadership naturally possessed by those of rank and to the heartfelt obedience of those who served under them. The latter could still be found in abundance at Greenwich, old sailors, the pensioned and policed veterans of naval warfare, who – when they were not to be found scattered around Greenwich Hospital like wreckage on the sea bed – were employed to serve as the mouthpieces for this sanctioned vision of the past (fig.1). As guides to the growing collection of portraits and seascapes hung in the nation’s ‘Naval Gallery’ (which covered the walls of the Painted Hall from 1824 onwards), the Pensioners’ attentive engagement with these art works was figured as an exemplary lesson in painting’s capacity to prompt and restore affective patriotism. As the journalist Henry Clarke put it in 1842:

Every blue-jacket [that is, every old sailor], may now … reclaim from oblivion some anecdote of courage or of kindness. An attentive public, in listening to the unaffected strain, will learn to respect the knowledge displayed, and the generous effusions of a brave man’s heart … From such observations a candid and judicious artist may learn how to improve his compositions: why some pictures … fail to call forth the feelings of an unsophisticated public; whilst … one of rude aspect, may kindle all the outward expression of deep-rooted sympathy.

The impact of such Pensioner soliloquies would therefore be perceived not only ‘in the improved taste … and in the improved feelings’ of that ‘attentive public’ but also in the output of contemporary artists who, listening to the sailor’s ekphrastic recovery ‘from oblivion’ of past officer-class merit, might ‘learn how to improve his compositions’ so that they appealed to the better sentiments of plebeian audiences.7 Moreover, by inhabiting a public exhibition space aimed at the articulation of conservative ideals to an audience of increasingly – and, to some minds, worryingly – socially enfranchised urban day-trippers, painting was made to illustrate self-sacrifice in the name of a greater good. Only then, Clarke claimed, are ‘the arts of peace’

made to put forth their best energies – to shed their lustre on the history of a nation’s bravest sons, and tempt the early germs of enthusiasm to rivalry with past greatness. This is the proper application of the art of painting.8

That medium appeared at Greenwich as a means of redressing the apparently diminished role of both élite example and popular heroism in a railway age, as a proactive presence capable of working its magic upon the political and moral sensibilities of its viewers decades, even centuries, after its own production.9

For Clarke (and he was merely echoed by the Naval Gallery’s other commentators), painting’s ‘proper application’ was to instantiate a past greatness that might thereby be raised up, resurfacing in the present to powerful (if reactionary) social and cultural effect.

This sense of painting’s ability to transcend the impact of change and the stark temporal difference wrought by modernity referenced the broader reconception of art’s powers which had been elaborated in aesthetic theory since the late eighteenth century. There, art had increasingly been deemed capable of challenging the distance not only between past and present but also between seeing and feeling.10

Furthermore, by the time that Clarke put pen to paper in the 1840s, the notion that both painters and their paintings might have such transformative effects on their viewers had come to be associated in particular with the works of one artist: Turner.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Fishermen at Sea (exhibited 1796)

Tate

In 1796, the year after the Naval Gallery had first been mooted, Fishermen at Sea (fig.2) appeared at the Royal Academy, the first oil painting to be exhibited by this artist, barely out of his teens. Hung (as was usual for lesser-known painters) in the Academy’s Ante Room, Fishermen at Sea shows Turner deploying his work’s relatively gloomy destination to his own ends by portraying the dazzling effects of searing moonlight as it emerges through a parting in the clouds to glow upon sea-water.11 As one reviewer noted, Turner had used significant artistic licence here to provide his scene with two pools of reflected moonlight rather than one; the overall effect was enough to draw his viewers in to gaze more closely upon his own public emergence and breakthrough as oil painter.12 Still almost unknown, Turner here produced a painting which – variously considered by exhibition critics to be the result of empirical observation or a more theoretical exercise in the laws of light – ‘has not its superior within the walls of the Academy’.13 It was not, one critic thought, an auspicious subject (‘Moon-lights are trite subjects’, he said) but Fishermen at Sea appeared to transcend the restrictions of literal meaning and cater immediately to its viewers’ capacity for aesthetic responsiveness. For exhibition critics, this was a picture about how things ‘dimly seen through the gloom of the night’ are indistinct and almost undeterminable, and how a boat might be about to be buoyed up by the ‘undulation’ of tidal waters.14 Indeed, this painting plays on contrasts of surface and depth just as it plays on the paradox of simultaneous illumination and obscurity. The sea’s unseen depths are therefore suggestively alluded to in the foreground study of light’s different effects upon and through water whilst, on the horizon, that water appears now as sheer sparkling surface.

‘As a sea-piece this picture is effective’, declared one critic, in a phrase which explains the work’s impact on the one hand and damns with faint praise on the other.15 For this was a genre which seemed to be practised only by artists who had (in the words of another) ‘too servilely followed the steps of each other, and given us Pictures more like japanned tea-boards, with ships and boats on a smooth and glassy surface, than adequate representations of that inconstant, boisterous and ever changing element’.16 Only Turner seemed to his commentators to have recognised the sea’s redesignation in contemporary culture as a space where, par excellence, transcendent mastery might be realised, and where the real extent of one’s physical, moral and aesthetic responsiveness might be revealed. As the Naval Chronicle (not a publication ordinarily given to philosophical enquiry) would put it in the 1790s, the sea appeared to its viewers only as it

exists in the mind of the beholder: if he does not possess a soul sufficiently enlarged to feel the sublimity and endless variety of such a scene, he should daily endeavour to awaken a sense within him, which either the force of habit has closed, or the want of a discriminating taste has never called forth.17

Through such statements (and students of literary romanticism will know they are not hard to find during this period), the sea was emphatically assigned the status of testing ground for a self able to convert the world into indicative sensual experience. At once deeply material and dematerialised, both ‘boisterous element’ and something existing ‘in the mind of the beholder’, the sea’s depiction presented Turner with distinct challenges, among which was the potential capacity of one possessed with ‘genius and judgment’ to revive a moribund pictorial genre as the grounds for an ‘effective’ art of aesthetic invention and experiment.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Shipwreck (exhibited 1805)

Tate

An analysis of Turner’s long engagement with these challenges, which lasted into his final years, would more than challenge the boundaries of this article. Certainly, we can find repeated evidence for his radically three-dimensional conception of the painted seascape as implying X, Y and Z co-ordinates, in images which push the planar significance of the genre’s conventional elements (see, for example, fig.3). To an unprecedented degree, foreground buoys are highlighted in his seascapes (in the images and their titles);18

ships tip towards us, capsized and sinking; men at sea appear to reach down into water to grab ropes, nets, bodies and oranges,19

or row away from us in boats bearing the anchors with which ships will be secured to the seabed.20

Elsewhere, anchors and mooring rings rest on shorelines between tidal waters and solid ground, where fish from the sea are laid out, filleted and consumed.21

This emphasis upon flotation and the possibility of descent towards a deeper ground serves not only to describe the sea as a gravitational body which both holds up and pulls down but also to draw our attention to the relation between surface and depth in a manner with metaphorical implications for the relationship between painting and the painter. Thus, while George Beaumont’s comment about Turner’s Calais Pier 1803 (National Gallery, London) that the water is ‘like the veins on a marble slab’ seems to describe the almost sculptural treatment of this element, that treatment nevertheless contains a pointed emphasis upon the white foam that salt water produces in its own wake, the sea serving not only to buoy up a human world but also as a surface upon which rough, involuntary and inchoate pattern is produced from somewhere beneath, in a manner analogous to the sketchbook and canvas of the modern responsive artist.

The multilayered relationship between surface and depth suggested here existed alongside an equally complex relationship between past and present in Turner’s work.22

As he matured into old age, Turner’s experience as a modern subject, existing in the as-yet uncharted space between these axes, would increasingly find concrete form in the transformation of his historical status wrought by the history of, and market for, art as it developed in the nineteenth century. At once a contemporary artist and an Old Master, his own absorption and transfiguration by painting alone was a process which Turner would reflect upon from his sixties and as he began ‘breaking up fast’ in his final years.23

Lying on his deathbed, cared for by the wife of a man who had drowned, Turner asked his fellow artist David Roberts a question which smacks of remarkable defiance against nature and history: ‘So I am to become a nonentity, am I?’24

The spectres of dissolution and its defiance repeatedly characterise his late seascapes, and it is on one of these – Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (fig.4) – that any discussion of Turner’s relationship with the sublimity of drowning must focus.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (exhibited 1842)

Tate

Exhibited as ‘Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth making Signals in Shallow Water, and going by the Lead. The Author was in this Storm on the Night the Ariel left Harwich’, this painting makes explicit claims (in its image and in its title) to first-hand experience. As so often in Turner’s work, that experience is one in which nature and human culture work across and against each other. In its confrontation with raw unassailable forces beyond human determination, that culture’s attempts to organise and cut through the world in its own interests (courtesy of engines, boats and straight-ahead navigation) are cast as a hubris familiar from ancient mythology. And in his desperate attempt to remain upright and proceed through space on his own terms – that is, to resist being stilled, swallowed and negated – man burns out both himself and his resources, the overworked engine that drives the boat’s thrashing wheel leaving a foul scorchmark across the sky. There, even the systematisation of the visual into language appears futile, the boat’s distress signal appearing little more than a transient spectacle already most clearly figured by its own feeble remnants: a rocket and red cinders falling, like Icarus and his feathers, into the sea.25

The vessel’s crew (indicated perhaps by a figure who reaches down to the water from directly beneath the mast) ‘go by the lead’, plumbing the depths in order to gauge their proximity to the bottom and to death.

That such an effort will result in only temporary and apparent truths is suggested by the water itself, which threatens at one point to pull the vessel down and at the next (and most especially in the left-hand side of the painting) to be capable of throwing it up into the heavens. Like the fold, the wave serves as a means of transporting bodies between and through different states:26

the subjects of Turner’s seascapes are swept up, down and along by his waves, and therefore undergo a giddying ‘alteration’27

between being borne aloft and consumed, between transcendence and decomposition.28

In this painting, the characteristically circular composition of his late seascapes acts as an engine, forcefully propelling the painting’s effects out and into our space, so that Turner’s waves serve as both figures and vehicles for an aesthetic experience in which the image might enfold its viewer.29

Yet the circular format also leaves us in little doubt about the real source and sole site of that experience: the artist, around whom the world seems to revolve and who compels its movements like a more powerful Canute.30

This painting is perhaps the pinnacle of Turner’s ability to carve multiple axes within pictorial space. At its heart is a large flash of whitish paint which might represent the glaring light cast by the flare, or the spray of towering waves similar to those we see in the foreground, or indeed the ghost of a sail (of a kind that Turner would hymn – and whose extinction he would seem to mourn – in The Sun of Venice Going to Sea fig.5 ).31

In any case, this area of the image also appears both as a highly worked patch of thick paint, at one point almost obliterating the boat’s mast, and as the compensatory interlude between glowering expanses of darkness which seem to press in upon it from all sides. The phantom of a figure (another of Turner’s onboard surrogates perhaps, to join ‘Van Tromp’ and Ulysses from earlier works) stands in its midst. Somewhere between field experiment and self experiment, Snow Storm signals Turner’s buccaneering desire to assume art in extremis, inserting himself into its raw force as heroic test case.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Sun of Venice Going to Sea (exhibited 1843)

Tate

In a painting which highlights the readiness of its ‘Author’ to find himself adrift from his cultural inheritance, compelled to devise his own pictorial materials, language and forms whilst exercising his own criteria about their use, it is significant that the resulting image depicts not a scene of clear departure or arrival but rather a moment out at sea and mid-voyage. Snow Storm is about artistic process (‘making Signals’) rather than product; indeed, it seems to be a signal fired off from the very midst of painting. What Turner reveals himself to have been caught up in here is therefore less the agonies involved in taking leave of tradition (or those of establishing the new) than the full whiteout of art itself, away from its ports of call.32

This painting therefore indicates – even beyond the titular myth of its origin – a substantial shift in the relationship between art and embodied knowledge. Since the late seventeenth century, marine painters had worked with a perspectival formula which enabled them to stage an expansive world of freely circulating bodies as if seen, known and gauged by an embodied viewer. In its systematic relation of horizon line and eye level, that formula was able to articulate a searching, speculative regard which was ambitious because it looked forward, projecting knowledge and possession out to vision’s furthest reaches. In turn, this perspectival formula helped to constitute the self as taking place before a visible world within which it found its capacities and its clear limits, an effect underlined by the marine painter’s established repertoire, which ran between calm and storm, the beautiful and the sublime. Turner shattered the horizon and, with that, this settled epistemology. Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth concerns itself not with knowledge of the world as an entity ‘over there’, but with knowledge of the self as an isolated body immersed within, and overtaken by, inchoate experience; system, whether perspectival or mechanical, has little purchase here. What Turner has observed (and simultaneously staged) is less the world and its elemental forms than the processes of painting and thought: this work seems to depict its own creation. In particular, the picture (its title opening with a blizzard of alliteration) performs the moment before knowledge, when vision, thought and bodily experience are effectively equivalent and have yet to tip over into the re-cognition that will define them as distinct, and differently valued, types of ‘knowledge’.33 A chaotic miasma from which form only hesitantly and incompletely emerges, Turner’s painting approximates the blank space – the khora, prior to knowledge, words and meaning – into which origins are born in philosophical thought. Significantly, this primordial state of suspended possibilities is no longer implied by the horizon but rather constitutes the entirety of the scene before us. Vaguely discernible within it is the upright human figure (the figure for but not necessarily of Turner himself) around which the image is organised. At once inside and outside the seascape, the artist is now its sole structural predicate, taking the place of both the horizon line and its viewer. Turner seems to speak to us from over there, from the underside of painting, matter and pure, asocial experience.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Peace - Burial at Sea (exhibited 1842)

Tate

He was, after all, an artist who apparently wanted to be buried in one of his pictures, and whose Royal Academy exhibits in 1842 included both this painting and Peace – Burial at Sea (fig.6), two works which between them triangulate painting, drowning and death.34

The purported subject-matter of Snow Storm implies the costs of such a voyage into the unknown: the possibility of a disaster which can only be kept at bay by the careful and constant monitoring of one’s proximity to the seabed, a perfect metaphor for the self-reflective, self-scrutinising methods of the artist, and indeed the individual, within modernity. Estranged from the safe havens of established convention by conspicuous historical change, the (artistic) subject was now obliged or liberated – Turner would have it both ways, practising a melancholic exuberance into old age – to travel under their own steam.

Read as an image of culture in tension with nature or as an allegory of artistic originality, Snow Storm shows Daedalus’s realm of human ingenuity and creation at once assaulted and reasserted. But his is not the only mythology conjured by this picture of tempest. In a veiled reference to the recent disaster of the Fairy (which had left Harwich in November 1840, sinking with all hands shortly afterwards), Turner’s title conjures the malign sprite Ariel from Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest.35

Turner’s evocation of this play is more than passing fancy or allusion.36

For, in his most significant intervention into the narrative, Ariel whispers into the ear of shipwrecked Ferdinand a beautiful lie about drowning:

Full fathoms five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.37

In Ariel’s song, Ferdinand’s father Alonso survives his drowning in mutated form, having been transformed into something ‘rich and strange’ courtesy of a merger with his new environment. Alonso has not vanished or faded but rather has undergone a liquefying ‘sea-change’, his difference from his surroundings diluted to the point that his body has become (in the words of the literature theorist Ian Baucom) ‘a catalog of the things that wash over it’, a body of work.38 As a figure for art’s capacity to deceive and delight, ‘Ariel’ also refers us back to Turner’s status as artist and, perhaps, to the sea itself, which appears in painting and play alike as a space of deception and artifice,39 reaching out like the sailor’s tropical delirium ‘calenture’ to challenge settled distinctions between high and low, art and sinking.40