Over the course of a little more than a decade Michael Landy made four major installations: Market 1990, Closing Down Sale 1992, Scrapheap Services 1995 and Break Down 2001. The third was acquired by Tate in 1997 and is the subject of this paper (fig.1).

Michael Landy CBE RA

Scrapheap Services (1995)

Tate

Although motivated by personal concerns, these four installations caught the mood of social change, labour market reforms and political ideology at the tail-end of the Thatcher era. This had a profound impact on the emerging, metropolitan art scene of the time. Blurring and investigating the gap between art and life preoccupied many artists during the period. This examination extended across a wide spectrum. Julian Opie, teacher of several of the emerging generation of artists, struck a detached, knowing stance by referring in his sculptures to products as diverse as model railway buildings, and modular screen and shelving systems. At the other end was the insertion of a rotting cow’s head in the original installation of Damien Hirst’s A Thousand Years 1990. The skinned head provided nutrition for the flies it bred, before they went on to be zapped by an ultra-violet fly-killer in a brutal ending of their life cycle.

In Market 1990 Landy investigated the activities of the ubiquitous corner grocer. In the front line of local retailing, these traders were caught in a financial squeeze as ever-larger supermarket developments sucked away their traditional customers. Landy’s Closing Down Sale 1992 epitomised a mounting sense of hopelessness in declining high streets where short-rent stores traded tatty junk and scratched a living at the margins of economic life. Art, too, was affected, with the prospect of galleries closing down during an extended recession. With people hunting for bargains, Landy was perhaps also referring to the worth and self-worth of the artist, and to the idea of art collecting governed by financial rather than aesthetic criteria. Scrapheap Services 1995 saw the birth of a shiny new enterprise to deal with unwanted rubbish. In this work Landy created a wholly bogus cleaning company to rid the world of useless human beings. While his intentions appeared completely sincere, no one could fail to see the ironies and absurdity intrinsic to its operation.

Scrapheap Services drew attention to the waste of human capital caused by firms shedding surplus staff in pursuit of cost-cutting and greater productivity. The heap of mulched waste produced in Scrapheap Services sparked the idea for Break Down 2001, Landy’s largest project, which he installed in a temporarily vacant, ground level department store in Oxford Street, London. Break Down was a semi-automated production (or, more accurately, destruction) line. After carefully listing everything he owned from paperclips to his car, Landy dismantled then pulverised the entire sum of his personal possessions. A sense of grinding hopelessness marked Landy’s first two projects which referred not just to the artist’s own career but also to his bleak view of the world at the time. Catharsis was the leitmotif of Scrapheap Services, while Break Down took the cycle of production, ownership and consumption to a radical extreme. It released Landy from the millstone of possessions and left him free to move on unencumbered by the past.

The trajectory of all these major projects must, however, necessarily be seen in the context of British art of the 1990s, dominated by what came to be called the ‘yBas’ (young British artists). The terms Britart and yBa were coined during the 1990s to describe the vigorous, young, mainly London-based art world of the period. As catch-phrases they were often used in parallel with the Britpop music scene of the time. They encapsulated a lifestyle in which the parties, celebrity and the network of relationships between those involved were sometimes as diverting as anything that actually came out of the artists’ studios, editing or recording suites.

These developments happened in parallel with increasing business support for the arts, where participation in the general buzz brought companies closer to their target demographic groups. Youth culture became the grail of broadcasting, and much marketing activity. The enterprise culture of the Thatcherite privatisations fed through into cultural enterprise. A growth in corporate sponsorship of the arts meant that many firms began to finance artistic activities with support in cash or kind. In the boom and bust of the 1980s and early 1990s, property developers began lending spaces to artist-run initiatives, rather than let them lie fallow: this was a way of enlivening the shells of unlet buildings. An extended recession in the early 1990s meant, in particular, that a surfeit of such spaces was available. Artists turned this to their advantage, much as an earlier generation had used derelict docklands sites as workshops and studios.

This inflow of financial investment introduced new sets of values. Art was perceived more readily as a commodity, to be acquired and sold. No insider-trading rules hampered those in the know, and great profits could be made from those artists whose work appreciated rapidly in value. With patrons such as Charles Saatchi, the lines blurred between collector, speculator and dealer. Artistic careers were made before collectors sold up and moved on. The idea of a collection as something gradually accumulated was overthrown by the increasing speed of recycling through the secondary market and auction houses; each iteration of Saatchi’s acquisitions took in a younger generation. New bodies of works were accompanied by publications that sought to identify a group spirit and a market profile to the batch of artists he was currently assembling. Saatchi’s speed of response, his getting in early at the degree shows, previewing before the opening, cornering the market by buying whole batches of an artist’s production and, more recently, by offering grants and in return getting early access or first pick of works made during the period, were strategies that drove the market forward. Several artists saw the value of their work appreciate many hundred-fold in the space of a few years, although they were not the ones who usually profited from this financially. Many other collectors rode the wave, although those who were less hungry usually picked up works at higher cost. The slower-moving public collections were unable to compete.

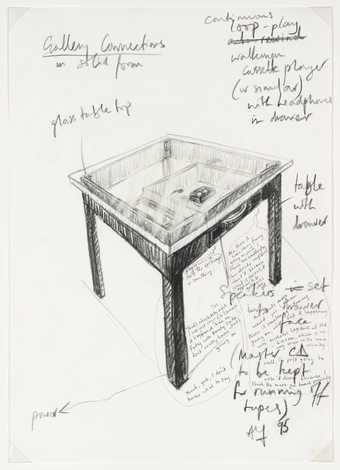

A new generation of advisors and consultants fed this increasing demand. They inaugurated or reinvigorated corporate collections, gradually turning tastes away from tried and tested art to more adventurous contemporary works. Generating this interest and surviving from the increased activity, many people began commercial or not-for-profit initiatives; starting magazines, working on projects, opening spaces, acting as agents. The writers Louisa Buck and Matthew Collings chronicled the galleries and key figures in their compendia of influential people and places. Dealer-impressarios such as the late Joshua Compston organised great gatherings (A Fête Worse than Death). He drove forward his activities with high octane energy but few resources. Angus Fairhurst made animated loops as projected backdrops to the sampled music played by his band. He also drew attention to the art world networks in his clever, subversive Gallery Connections (1991–6), in which he instigated involuntary telephone conversations by ringing two people working in galleries simultaneously and holding the handsets together (fig.2).

Angus Fairhurst

Gallery Connections (1995)

Tate

Blue chip West End galleries were challenged by upstarts setting up everywhere other than the traditional Cork Street/Bond Street axis. The surprise was that, rather than acting as feeder galleries taking young artists through their first shows before seeing them cherry-picked by more established, better financed and better connected dealers, these younger galleries, with few exceptions, held on to their artists. To counter this, the established dealers hired younger hands closer to the scene, who selected special shows and commissioned artist’s projects. When artists left their dealers it was more often for personal reasons than to seek commercial representation elsewhere. Many artists relied on their own initiative; the East End shop run by Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas, and Emin’s subsequent studio/store in Waterloo is perhaps the best example of careers germinating outside the gallery network. Even after she joined the gallery White Cube, Emin kept on the shop in Waterloo for several years, before handing it over to another artist, Sarah Staton. She also called her 1994 show at White Cube My Major Retrospective, just in case her first solo show was also her last.

The now legendary beginning of the 1990s phenomenon, what came to be called ‘yBa’s, happened with the Freeze exhibition in 1988. With a catalogue sponsored by Olympia and York, developers of Canary Wharf, Damien Hirst (as selector and exhibitor) and a group of students from Goldsmith’s College of Art organised a showcase for their works. The strength of the group and the art they made was cemented by the close relations among the exhibiting artists. The social networks visible here already gave the signals for more intimate relations, Michael Landy with Abigail Lane, Sarah Lucas with Gary Hume, Fiona Rae with Stephen Park. These networks facilitated the exchange of ideas and provision of mutual support, these and other artists offered each other during the years that followed. These links persisted in the artists’ choice of commercial representation, with many (Hirst, Fairhurst, Hume, all in Freeze) represented by Jay Jopling’s White Cube Gallery by the mid 1990s. Landy, like several others, initally joined the dealer Karsten Schubert, before leaving him in the early 1990s to go it alone, apart from a brief spell with the Waddington Galleries.

Freeze became something of a model for other warehouse shows. The most enterprising were those organised by Carl Freedman and Billee Sellman in a Bermondsey ex-factory they called Building One. In 1990 Modern Medicine with, among others, Hirst, Lane, Fairhurst, Mat Collishaw and Dominic Denis, all of whom had exhibited in Freeze, was followed by Gambler with Hirst, Fairhurst, Lane and several others. They were joined by Tim Head, an older British artist. Inviting more established figures to show alongside the younger generation became something of a pattern in later shows; Landy’s artistic mentors Michael Craig-Martin and Julian Opie showed alongside him at the Goldsmith’s Gallery in 1991, and Gilbert & George showed with Collishaw, Lucas, Hume, Emin et al in Minky Manky at the South London Gallery in 1995.

The group phenomenon was identifiable in the late 1980s and entrenched in the public mind by the mid 1990s through articles that penetrated beyond the specialist art press into the news pages of the broadsheets and tabloids. Such coverage broadened to include others of the generation. The presence of a core of Freeze artists or those subsequently closely associated with it was exploited as a publicity device for a whole generation of artists whether they conformed to those origins or not. Like all group labels, many artists who were included in international shows dedicated to young British artists neither counted themselves part of it nor necessarily actively disassociated themselves. A media myth of origin had taken on its own momentum. These exhibitions, such as Football Karaoke (1994), organised by Georg Herold for the Portikus, Frankfurt, Brilliant! (Walker Art Centre Minneapolis, 1995-6) and Full House (Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 1996–7) preceded Sensation (1997), the first major show of young British art to be mounted in Britain. Held at the Royal Academy, it comprised exclusively of works from the Saatchi collection.

The umbrella over ‘cool Britannia’, a slogan that accompanied the accession to power of New Labour in 1997, covered any group show, particularly when certain key names kept recurring: first Hirst, Hume, Lucas and others; later Jake & Dinos Chapman, Tracey Emin, Chris Ofili (still in 1996 a ‘relative unknown’, according to Brilliant! selector Richard Flood), Sam Taylor-Wood, Gillian Wearing and Jane & Louise Wilson. The group identity, as much constructed as self generated, was exceptionally strong. Individual voices, however, gave the 1990s generation of emerging British artists an unusually broad base. There were those, such as Rachel Whiteread, Steve McQueen, Tacita Dean, Anya Gallaccio, Mark Wallinger and Steven Pippin, who were, in the main, less exposed to the whirlwind of media interest generated by the young British artist phenomenon. As in the case of the controversy around the demolition of Whiteread’s House in 1993, however, a withdrawal was not always possible. Commercially, this broad level of activity was sustained by White Cube, Interim Art, Anthony Reynolds, Victoria Miro and many other more recently established galleries. Institutional sanction was given by the Tate through the Turner Prize: by the early 1990s a generation of artists in their late twenties and early thirties emerged as a dominant force among the short-listed artists and winners.

Michael Landy’s Market, his first large solo show, followed Gambler in the autumn of 1990. The expansive floor area of Building One gave him an opportunity for the first time to construct an installation on an ambitious scale. He used the collapsible, stepped metal stands, stacks of plastic crates and sheets of fake grass familiar from the pavement displays at many British corner shops. Characteristically, Landy took them unchanged from the consumer world but created new structures within the organisation of Market. However, while apparently dangling before the visitor to Building One the promise of goods for sale, he omitted any objects that could be traded, really the only reason for making such a display. Landy’s use of only the physical props for presenting consumer goods created, paradoxically, a value-added increase in their own worth through their designation by him as art objects. The evident lack of available wares was at once a subversion of the normal market expectations of supply and demand, and the establishment of further intangible values built round ideas of exclusivity that attach to luxury items such as designer goods or art.

In Market Landy followed a twin strategy of deploying the objects in a way that could closely refer at one and the same time to everyday life and to art. On the one hand he mimicked the habitual practice of the greengrocer ritually building a display for fruit and vegetables in front of the shop, the subject of the Appropriations videos shown in the installation. On the other, he acknowledged the use by 1960s minimalist and conceptual artists of industrially produced, readily available materials arranged by the artist into variable or sequential patterns. This twin connection was already evident in Landy’s slightly earlier plastic-sheeting tarpaulin works, such as Sovereign (1988) that he showed in Freeze. Clipped and knotted differently each time they were installed, to create new creases and folds, these works were indebted to the contingent arrangements of objects and elements in works by Michael Craig-Martin, probably the most influential of Landy’s teachers at Goldsmith’s College. Landy’s titling of his plastic crates as Stacks also acknowledged Donald Judd’s vertical arrangements of identical, untitled sculptural elements, informally also known as ‘stacks’, even though the humble readymades Landy appropriated contrasted greatly with the beautiful surfaces and shiny finish of many of Judd’s sculptures.

If Market offered the opportunity to make work on the grand scale it was an ambition realised on slender means. Landy acknowledged many collectors, critics, gallerists and fellow artists for their contributions. This pattern of support was repeated for almost all his major projects over the coming decade. As with most of his projects, Landy accepted such assistance mainly for the realisation of his installations, not for their conception or during the gradual assembly of his materials. The idea for Scrapheap Services formed quickly in the artist’s mind: the execution of it, however, was arduous and drawn out. It took about three years to complete.1 According to Landy, the final work was much larger than he originally intended. This was mainly, he recollected, because he did not want to let go of the project. Later he also became more aware of the level of detail in its expanded form. During 1993-4 it had also become clear that Landy’s concept had outgrown the space available at the Karsten Schubert Gallery in Charlotte Street, where he originally planned to show it.

In spite of its subject, the formation of a bogus cleaning company the sole purpose of which was getting rid of unproductive people, Landy’s reasons for making the piece were as much personal as a response to the political realities of the day. In an interview given to Douglas Fogle in February 1995 Landy cited anger as the chief motivating force behind his work.2 Trying to formulate an artistic response to those feelings was difficult, he said, and evolved, eventually, into Scrapheap Services. Put simply, Landy had found a way in his art to address the policy initiated by the Conservative governments of the 1980s of creating private companies from national industries. Many of these firms simply became private monopolies. Thereafter driven by the demands of shareholders, one of the chief human outcomes of privatisation was the demand for labour market flexibility. In practice, this usually meant cutting staff.

Making Scrapheap Services presented Landy with the prospect of continuing to work as an artist, even though the prospects for the project were uncertain. When he began working on it he was not being widely exhibited; his Closing Down Sale exhibition in 1992 had appeared to sum up the direction his fledgling art career was taking (fig.3). Installed at Karsten Schubert’s gallery, Closing Down Sale, with its supermarket trolleys and cheap, garish fly-posters alluded to the marketing strategies of consumer economics at the bargain end of the spectrum. Even here, though, Landy said he enjoyed the fact that this once-in-a-lifetime sale mounted at the height of the recession should be a one-off event, never to be seen again. His reluctance to make art that could easily be sold, a radical response to the economic system that provided the conceptual framework for his art, was already clear. Fogle asked Landy about the aesthetic of expendability which he identified in Landy’s work and also in the work of many other artists of the time. Landy’s answer addressed less the trashy materials he was using, more the need which he felt to act in the present without thought for the future or of making something that would endure.

Michael Landy CBE RA

Cor! What a Bargain! (1992)

Tate

Like many people at the time, Landy went on a Government Jobstart course and found he was soon fending off offers of unskilled jobs stacking shelves in supermarkets. He recollected that working towards creating his own cleaning company gave him ‘gainful employment’3 and stopped him feeling the emotions of being unwanted, which is common in many people looking for work. By taking on responsibility for conceiving and constructing his own company/artwork, moreover, he felt he could stop blaming others for the state of his life and career. Landy evolved the routines for gathering raw materials and producing or sourcing items for Scrapheap Services, happy that he was both following his artistic vocation and knowing that he would be fully occupied from one day to the next.

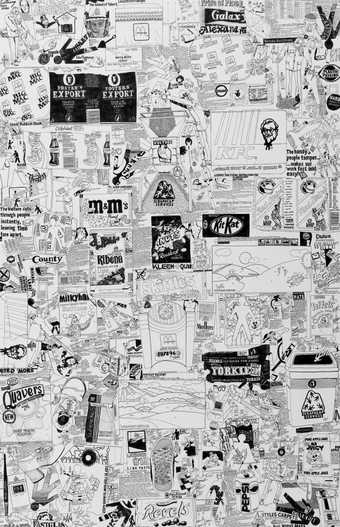

He instigated a cottage industry to create the thousands of small figures for Scrapheap Services. They are the basic, statistical units of the installation; that is to say the uncounted and uncountable mass of de-individualised existences wasted by society but nonetheless needing to be processed. This should preferably be by a private contractor making a profit. Landy fabricated each of them from litter he collected every day on his walk from home in Peckham to his studio in Brixton, or retrieved from dustbins near a local burger bar. In spite of the sheer laboriousness of this approach, he said that he never ‘got round to a quicker process’.4 His rudimentary production method meant working in sequence on different batches of materials. Following the collection of this rubbish in plastic sacks, his routine was to flatten the cans and packaging materials before impressing the contours of the small figures using stencils he had fabricated. He hammered the stencils with a large mallet, to imprint their forms into the materials that he had salvaged.

Each evening Landy released the figure shapes from the surrounding materials. Some, in polystyrene, came away easily while others, impressed in metal, needed more effort to peel away. Landy undertook the numbing repetitiveness of this task, by which he created literally thousands of identical, small figures, while watching TV. Having pressed them out he then crumpled each figure by hand, shaping them like curled autumn leaves. This meant that they crunched underfoot when walked on, an unavoidable consequence in the finished installation, because Landy has covered the floor with the little figures wherever he has installed the work.5 By slightly crumpling each figure Landy found a simple way of making anyone walking through the installation complicit in the results of his labours and party to the symbolic waste of human potential. Shaping each figure, moreover, represented a moment of special, individual attention that he had given these found materials by his laborious artistic activity. Without irony or finger-wagging but aware of the tragic absurdity of life, Landy inevitably drew attention through the litter trodden on in the installation, to the equally ignored swirling mounds of rubbish and the fraying social fabric in Peckham where he lived at the time.

While the myriad small figures are the most numerous element of Scrapheap Services, other components are more eye-catching. The ‘vulture’, a receptacle and destination for all the detritus, stands over three metres high. It was adapted from a standard chipper machine, usually used for shredding foliage. Landy’s design modifications were executed by Mike Smith, specialist fabricator of many artworks, including the steel and glass cages used by Hirst. In the company promotional video that Landy made to show in the installation, the vulture’s engine is running. This is an aspect of truth to materials and their continued functioning that Landy insisted upon, even when these objects are transformed into a work of art. The mechanical vulture would, according to the artist, feed on the human carrion abandoned by society and expel it as shredded waste on the floor beneath. Striking a note of unlikely optimism Landy said in his interview with Fogle, ‘it would be nice one day to be able to recycle the heap into something else’. That is the message, perhaps, more forcefully conveyed by the idyllic scenes on the stove enamel signs in Scrapheap Services. Here, though, a moment of doubt occurs. As optimistic pointers to the future rather than a bitter commentary on the present, these signs are perhaps a rare instance in the installation when Landy’s honesty in addressing social ills could tip over into satire and cynisim.

The other elements in the installation conform to a similar pattern of availability in the marketplace followed by adaptation by the artist. Landy sourced the manikins, bins, bags, brooms, ‘people-pikkas’ and signs from existing suppliers, relying on real manufacturing processes in the formation of his artwork. In this he encountered the traditional gap between the more bespoke needs of the artist and an increasing standardisation of product design. Although he only needed around 200 refuse sacks, the minimum order required was 2000. When they were delivered Landy discovered that the plastic sacks needed heating to stretch over the standard municipal bins he had bought. A firm called Alphabet Embroidery supplied the fabric logos. These logos were designed by Landy, based on pictograms widely used on existing street furniture and stitched on to the red, trade-standard jackets (from Alexander workware) and baseball caps.

In specifying the uses of these props and making the necessary modifications to have them suit his purposes, Landy received the kind of support from fellow artists and collaborators that has remained part of the ethos of British artists of his generation. Jake Chapman, then constructing modified life-sized manikin figures with his brother Dinos, showed Landy how to sever and re-attach the dummies’ limbs to give them the more dynamic poses they would need to wield the brooms and push the litter carts in Landy’s installation. Tim Olden, then boyfriend of Esther Lane, the sister of Landy’s own girlfriend of the time, Abigail Lane, helped him shoot the video for Scrapheap Services. Peter Chater did the voice-over and the vaguely familiar ‘Uh-oh!’ was in fact sampled from Family Fortunes, a TV programme hosted by Les Dennis.6

Lane herself appears on many of the detailed drawings that Landy made mainly between spring 1995 and December 1996 while working on the installation.7 Through these highly intricate drawings he explored the minutiae of rubbish collection vehicles, vessels, utensils, processes, techniques and operations. Although he made many of them after the installation was nearing completion, Landy explained that drawing helped him formulate his ideas without the distraction of phone calls and other interruptions. They also became visual diaries in which he recorded events in his private life. Such obsessional detail is a hallmark of Landy’s style. It reflects an all-enveloping approach, in which his entire existence is wrapped up in the realisation of a work-in-progress. Complete immersion enables Landy to create and inhabit an imaginary universe. He imprints his artistic personality indelibly on his material through a level of super-elaboration and by the blanket imposition of his own logos and branding devices. By expressing a relentless preoccupation with process and minute observation in the thirty or so tightly packed Scrapheap Services drawings (fig.4). Landy created an apparently endless set of variants on its context, materials and processes. These were eventually distilled into a set of key components and operations in the sculptural installation.

Michael Landy CBE RA

Sweep to Victory (1996)

Tate

By mid 1994 the requirement for a large space to show the work together with the cost of all its parts, led a group of dealer friends to begin sponsoring it: a seamless continuation of the art world support network that had backed, for pleasure or profit, many of the semi-commercial warehouse projects of the late 1980s and early 1990s. In July 1994 Landy began making a series of multiples to raise funds. The first, a photograph taken in the artist’s Brixton studio by Edward Woodman, showed Landy wearing the red uniform of a Scrapheap Services operative. It was bought by, among others, Sadie Coles, who was shortly to leave the Anthony d’Offay Gallery to set up Sadie Coles HQ, and the independent dealer Helen van der Meij. Those funds were put towards buying further uniforms and litter bins. Several other editioned works followed. They included: a photograph showing a hand dropping the cut-out figures into a bin; a wall-mounted litter bin; and a refuse bag containing cut-out figures. Richard Deacon, who introduced Landy’s work to Marian Goodman his New York dealer, also acquired one of the multiples. All twelve editioned works were shown at Ridinghouse Editions from December 1995–January 1996 and published in a small artist’s book in the summer of 1996. The first drawing related to Scrapheap Services made in the autumn of 1994 went to Marian Goodman, who had given financial assistance so that Landy could begin work in earnest. Around the same time Helen von der Meij provided some funds to make the promotional video.

When Landy finally came to install Scrapheap Services in late 1995 he had to wait until the third time he did so, six months after the first installation, before he could attain the right ambience of brightly illuminated sterility. In early 1995 Landy had turned down an offer to show the installation in Manchester because the space was not suitable. By June that year grants from both the Henry Moore Foundation and the Arts Council (to make the enamel signs), enabled Landy to complete critical elements of the work. Richard Flood, visiting London while preparing Brilliant!, invited Landy to participate. Landy agreed, but owing to space limitations in the museum, the work was shown in a disused soap factory a ten-minute drive away from the Walker Art Center.

It was hailed as one of the outstanding works shown in Brilliant!. The support of the Henry Moore Foundation and the involvement of Judy Adam as project coordinator, a role she had had since November 1994, led to a renewed attempt to show Scrapheap Services in Britain. Between March and April 1996 it went on display in Leeds, in another disused factory, the Electric Press Building. Finally, an offer from the Chisenhale Gallery enabled Landy to create the ideal environment he wanted for the work. Principally, this was the addition of a pale vinyl floor and a high level of fluorescent light from standard tube fittings. Fellow artists Paul Noble, Adam Chodzko and Keith Coventry assisted during the installation.8 A similar, artificial environment, more sterile than the distressed interiors of the abandoned factories in Minneapolis and Leeds, was created in the 1979 extension of the Tate Gallery at Millbank when the work was displayed in 1998, a year after its acquisition.

By then Landy had launched himself into work on Break Down, his next large project. The clarity of the message in Landy’s installations, with their high level of detail but easy legibility and apparent lack of complexity, often has a simple starting point but is achieved through a protracted period of gestation. While making Scrapheap Services Landy continued to be directed by his vocation as an artist through the simple act of creating routines of work each day, following precisely the logic of capitalism in the creation of wealth (and worth) through production. Where Landy slips the net of this logic, can be observed in the ray of optimism, even idealism, that shines through all his work. This is present in the potential for renewal even in the mulched figures under the vulture in Scrapheap Services. In Break Down Landy felt he was at one and the same time attending his own funeral, and killing off a part of himself and his identity by systematically destroying the objects that defined him. He was also liberating himself from the memories and associations that people project on to objects. By forbidding visitors to the installation from crossing the yellow tape separating them from the moving (dis-)assembly line, Landy also obliged the spectator to confront a pyschological barrier: that of coveting the objects being dismantled. In this case it was the extra value given them because Landy owned them or, additionally, because in the case of art works given him by artist friends, they had high financial worth as well. As the critic Claire Bishop writes, ‘It doesn’t matter if Landy owns that catalogue, or if I own that catalogue …: it’s just an object. We don’t need it and can cope without it. It’s pure covetousness that gets us obsessing over this stuff’.9

Crossing the lines of art and life continues to be Landy’s primary concern. However, Landy radicalises this relationship by synthesising as his raw material the messages and structures of the market economy and its attendant management jargon, logos, branding and narrowly contractual definitions of liability and responsibility.10 The operations of his artistically defined processes are achieved with huge stamina and patent sincerity. Through them Landy illuminates the casual wastefulness of consumer society while drawing our close attention to its mechanisms: we are complicit spectators of his artworks because we are also in them.