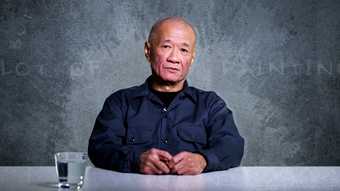

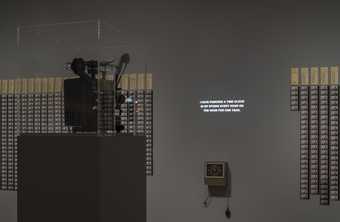

Born in Taiwan in 1950, Hsieh is best known for the one-year performances he undertook while living in New York from the 1970s onwards. One of these performances, Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981) 1980–1981, involved punching a time clock every hour for a year. It was on display at Tate Modern until June 2018. Striking in his commitment to these physically and mentally gruelling works, Hsieh nonetheless remained in relative obscurity for the majority of his career.

Tehching Hsieh

Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981) 1980–1

Tate T13875

© Tehching Hsieh

However, as Richard Martin, Curator of Public Programmes at Tate, noted in his welcome address, in recent decades the significance of Hsieh’s work has been recognised more widely. Unsurprisingly, this recognition has coincided with Hsieh’s emergence from a self-imposed thirteen-year ‘exile’ from art-making in 1999, and his subsequent shift from producing art to publicising and disseminating it, resulting for example in an exhibition of his work at MoMA in 2009 and Tate’s acquisition of Time Clock Piece in 2013. This is not to mention the scholarship of Adrian Heathfield and praise from Marina Abramović. People are indeed paying attention: as Martin explained, the pioneering artist has had a marked influence on Time Well Spent, the Tate Exchange-organised programme of events of which the talk was part. Focusing on notions of productivity and unproductivity, the programme provided a useful framework for thinking through Hsieh’s performances.

Hsieh’s far-reaching appeal can also be felt in the writing of Queen Mary University undergraduate Ash Dilks, whose words were used by chair Lois Keidan of the Live Art Development Agency (LADA) to introduce the artist. Hsieh, writes Dilks, ‘has taken art to the limits of what is feasible and possible’ through his attempts to collapse the boundaries between what Hsieh calls ‘art time’ and ‘life time’ in his mentally and physically demanding one-year performances. Dilks is right to disavow any significant connection between Hsieh’s performances and the happenings and conceptual art of 1970s America, a vital observation in light of the lingering tendency to view art from non-Western artists as somehow derivative, although perhaps more could have been done to discourage overly autobiographical readings of the kind Hsieh would explicitly reject later in the talk. Most importantly, Dilks’s words served as a concise but insightful survey for those unfamiliar with Hsieh’s artworks. He covered Hsieh’s early performances in Taiwan, which Hsieh has labelled ‘not mature’, through to the better known ‘one-year’ works in New York and finishing with Hsieh’s thirteen-year ‘disappearance’, which ended in 2000.

Dilks’s words also touch upon two themes that Hsieh took up in his own presentation. One of these is the charged relationship between a performance and its trace – the document. Hsieh’s current project involves assembling an exhibition of his life works. One well-trodden issue that this raises is the disjuncture between his extended, demanding performances and their representation in text, photography and film, which Heathfield discussed in the 2012 monograph Out of Now: The Lifeworks of Tehching Hsieh. But an additional issue that Hsieh mentioned during his presentation was the challenge of transmuting the thirty-year period of his performances into the rooms of an exhibition – in other words, the task of translating time into space. Hsieh revealed that he has attempted to work around this by ascribing a room to each year-long performance (with a longer room for his Thirteen Year Plan) and representing the varying lengths of ‘life time’ occurring between his performances with smaller rooms of different proportions. His solution attends to the complex connection between performance and document, and time and space, and is highly relevant to museum and gallery practitioners today. This is especially pertinent as performance moved from ‘outside’ the museums to within them when museums began to aquire performance works, a move which undoubtably changed the radical potential of performance. This is no less true for Tate, as Keidan also highlighted.

Tehching Hsieh

Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981) 1980–1

Tate T13875

© Tehching Hsieh

Tehching Hsieh

Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981) 1980–1

Tate T13875

© Tehching Hsieh

Another significant theme that the artist took up is time. Hsieh outlined the premise which forms the basis of each of his one-year performances: that a fundamental ‘precondition’ of all life is the passing of time, or that ‘life is a life sentence’. In his work, Hsieh explores this precondition by stripping down his performances to a few basic activities such as ‘waiting’ (as in Time Clock Piece) or ‘walking’ (as in Outdoor Piece, in which Hsieh spent a year on the streets of New York and documented his daily perambulations on maps). As a riposte to readings of his work which overdetermine Hsieh’s Taiwanese identity and ignore Kafka and Dostoyevsky as key inspriations, Hsieh clarified that his goal here is not to attain some kind of transcendent, zen-like state. Nor are his performances about passing time: rather, his performances are passing time, as emphasised in their long durations. This is one way in which Hsieh attempts to bridge the gap between ‘art time’ and ‘life time’.

Amelia Groom’s response to Time Clock Piece built upon Hsieh’s discussion, focusing in particular on the multiple temporalities imbricated in this work and its potential to question conventional understandings of time. For Groom, the 133 times that Hsieh failed to punch the clock out of a possible 8,760 are a vital component of the work as they highlight the conflict between corporeal time – the time of circadian rhythms, for example – and clock time. And though the time-lapsed film of the performance (a stop-action record made up of the 8,267 photograms taken when Hsieh did punch the clock) condenses the time of the 365-day performance into a six-minute film, it also registers an otherwise barely detectable corporeal time as the artist’s hair grows and his face bears greater signs of fatigue with the passing of the year.

For Groom, part of the radical potential of Hsieh’s performances lies in their laying bare of the disjuncture between different temporalities – what Hsieh here called the ‘repetitive’ and ‘beautiful rhythms’ to which human life is consigned. Through an entertaining and illuminating comparison to the 1980 film and song 9 to 5, Groom demonstrated how Time Clock Piece in particular speaks to the constructed nature of clock time and its derivative, the relentlessly productive ‘work time’ of capitalism, which the work challenges in what Dilks calls its ‘radically unproductive’ nature. Groom ended by drawing attention to the fact that, unlike the song,Time Clock Piece remains pertinent to experiences of labour in the twenty-first century, arguing that the artist’s endless commitment to the hourly punching of a clock anticipates the pervasiveness of ‘work time’ today, spilling over into ‘non-work time’ with the spread of flexible working hours and mobile communications technology.

In response to the final question from the audience, Hsieh reiterated the idea that his works are not about a specific time – time spent as an illegal immigrant in the United States, for example – nor about the past in general. Rather, his performances address pure time, the constantly renewing time of the present in which we all live. For this reason alone, Hsieh’s explorations are likely to continue to captivate in decades to come – and his Time Clock Piece is a monumental addition to Tate’s permanent collection.