Tehching Hsieh

© Guardian News & Media Ltd 2017, photo: Anna Kucera

Marina Abramović

© Reto Guntli

MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ Why was it so important to make five long-durational pieces of one year each?

TEHCHING HSIEH The idea for each came one at a time. While doing one piece, I would think of what to do next. When I was doing the Cage Piece, I was doing time. I thought I would continue this idea by using a time clock to record doing time. My performance works show different perspectives of thinking about life. But the perspectives are all based on the same preconditions: life is a life sentence; life is passing time; life is freethinking. One year is a basic unit for human beings to calculate life, and it is also the time the earth takes to circle the sun. I like to use real time; this allows me to live in art time, and to think freely.

In your work, Marina, sometimes the duration is governed by the limits of your body. But sometimes it’s a set time. How do you decide the duration of a performance?

MA There are several factors to take into consideration. Mostly, it has to do with the institution itself – the museum or the gallery gives you a specific amount of time. I call this ‘given time’. Then I have to deal with that restriction in order to create the work. Sometimes I have the freedom to decide the duration. Then I have to deal with my own body’s limits to understand how long I can push myself.

What made you decide that it needed to be one year rather than any other amount of time?

TH One year is a complete cycle of calculating life. If the time were longer than one year, the performance would have become about endurance. When it’s shorter than one year, it doesn’t complete the cycle. To me, life is linear: it goes in one direction. You cannot say yesterday is tomorrow. You cannot go back. In life there is always something new. But at the same time there is much repetition: nothing new. So a cycle. That’s what I want to say: it is about living. Just living.

MA During the period the work was executed, your body needed to go through extreme discipline. How did you train yourself to be able to generate that kind of stamina and willpower?

Marina Abramović, Rhythm 0 1974, 6-hour performance, Studio Morra, Naples.

This work, which took place at Studio Morra in 1974, involved Abramović standing still while the audience was invited to do to her whatever they wished, using one of 72 objects she had placed on a table. These included a rose, a feather, perfume, honey, bread, grapes, wine, scissors, a scalpel, nails, a metal bar and a gun that could be loaded with a bullet, which was also provided. As Abramović described it later: 'What I learned was that ... if you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you.'

© Marina Abramović, courtesy Marina Abranović Archives

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1980 – 1981 (often called Time Clock Piece), New York.

Hsieh set himself the task of clocking in and photographing himself every hour for one year.

© 1981 Tehching Hsieh, courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York, photo: Michael Shen

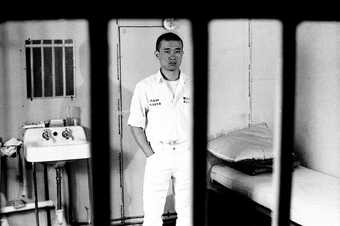

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1978 – 1979 (often called Cage Piece), New York.

Hsieh spent a full year locked inside a wooden cage he built himself in his second-floor studio at 111 Hudson Street, New York.

© 1979 Tehching Hsieh, courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York, photo: Cheng Wei Kuong

TH I had to test each one-year performance for one week. If I knew from the test I couldn't make it through, even if it was a good idea, I wouldn’t do it. To me it doesn’t matter whether you have negative energy or positive energy. You just do it. I did not develop my technique. I was not like ‘Grasshopper’ in the Kung Fu TV series, using his memory of the wisdom of his master to know how to move. Of course, you need to use life experience and practice to help you face the difficulties in the work. There is a lot of thinking to do, day by day. But that kind of willpower comes from the oneness of life and art. It comes naturally.

Maybe this is a difference between our philosophies? Your idea of training to do duration is more a spiritual practice?

MA Yes, I think there is a difference and a similarity at the same time. Even if you maybe don’t accept that your durational work is spiritual, I think it is, and mine is as well. It is about a state of mind and being in the present, about simplicity, about performing and living at the same time.

What kind of changes did your mind undergo during the process of a work?

TH I was not trying to feel different from normal. I needed to feel strong. Not changing was more important to me. I was not thinking much about my mind. Of course my thinking in the ‘art time’ of the performance was different: I dealt less with reality. In some pieces I had plenty of time for thinking. In others I had to be in control a lot of the time or the piece would fall apart, so I just had to deal with keeping it going, following the rule. I took care of myself, and thought about what I had to do next. It’s like being a sick man in a doctor’s office waiting for the appointment: it’s best you don’t have too strong energy, don’t have a need. So I just sit there thinking. I just deal with what happens. My survival is more like that: simple, low-class, primitive. Just passing time.

Ulay/Marina Abramović, Rest Energy 1980, 4-minute performance for video, ROSC '80, Dublin.

Abramović and fellow artist Ulay stand in front of one another looking each other straight in the eye. She holds a bow and he the string with the arrow pointing directly at her heart. Both lean back slightly, tensioning the bowstring ready to fire. Microphones record the increasing rate of their heartbeats.

© Ulay/Marina Abramović, courtesy Marina Abramović Archives

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1981–1982 (often called Outdoor Piece), New York.

Armed with a sleeping bag, Hsieh stayed outside in the streets and parks of New York City, forbidding himself from entering any kind of building or shelter.

© 1982 Tehching Hsieh, courtesy the artist, The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection, Detroit, and Sean Kelly, New York

MA It is interesting that you say this, because in my opinion your statement is very spiritual. It is so striking that after your five long-durational pieces you decided not to perform anymore. What led to this decision?

TH The last one-year performance, No Art Piece, was a decisive factor. The time between each performance is ‘life time’, and I didn’t want to make that time longer than one year. The gap between the No Art Piece and the previous Rope Piece was 361 days. I still had no idea what to do next, so I took up the idea to do no art, have nothing to do with art. After this piece, it was hard to go back to doing art. That’s how the last piece, Thirteen Year Plan, came about – I made a rule so that I could do art without showing it publicly. I did start one new piece within the Thirteen Year Plan, called Disappearance. Like a Russian doll: one thing inside another, I wanted to start another life as a stranger. I disappeared from New York and from people who knew me for half a year. I wanted to keep going until the end of the 13 years. I didn’t finish that piece. If it was only for art, I could have finished it. I kept exiling myself, first from the art world and then from the life I was living. It was too heavy, so I stopped that work. Then I stopped doing art altogether after 2000 when the Thirteen Year Plan had finished. I went back to life itself, and it became an exit for me. Artists live for making art, or totally retreat from the art world, otherwise death can be a clear answer. I still have a voice in the art world, but more as a witness; I’m a sub-artist.

You’ve been dedicating your life to art for more than 40 years now, and you are an inspiration for different generations. Does art answer all your questions for life?

Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano, Art/Life: One Year Performance 1983–1984 (often called Rope Piece), New York.

Hsieh spent a full year tied to the artist Linda Montano with an 8ft rope. They were not allowed to touch one another.

© Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano, courtesy the artists and Sean Kelly, New York, photos: Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano

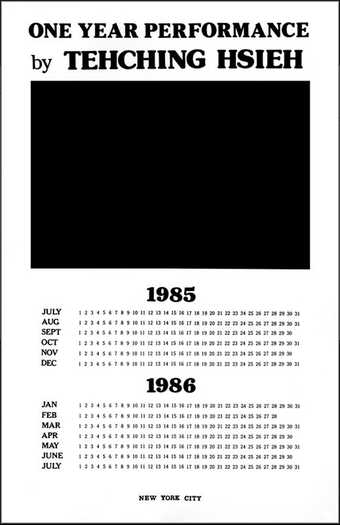

Tehching Hsieh, poster for One Year Performance 1985-1986 (often called No Art Piece).

Hsieh denied himself any contact with and refused to talk about art – 'I just go in life,' read the artist's statement.

© 1986 Tehching Hsieh, courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York

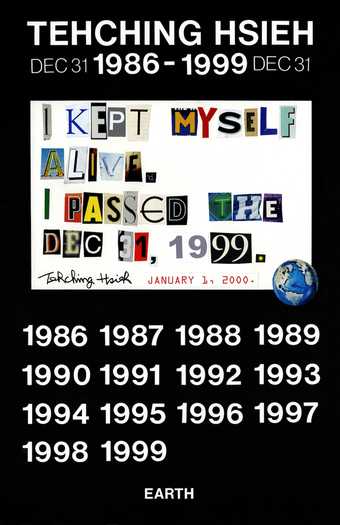

Tehching Hsieh, final poster for Tehching Hsieh 1986-1999 (often called Thirteen Year Plan).

For a final documented piece lasting from 1986 to 1999 (from his 36th to 49th birthdays), Hsieh promised to make art, but not show it publicly.

© 1999 Tehching Hsieh, courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York

MA For me, art is just a tool that I use in order to understand life. And at this moment of my life I am also busy, like you, with this idea of disappearance. Recently, I have been interested in creating community events, where my presence functions more as a witness than a performer.

Did your life change your work, or your work change your life?

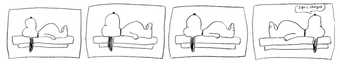

TH My life is the foundation of my work, and my work has the quality of life – I lived in my work. Life and work could not be separated. Doing art and doing life are the same, they both are doing time. And we try to find different ways to do time. I remember when I was doing the Time Clock Piece I saw a Peanuts cartoon. I’ve drawn it for you. It’s just like Snoopy says: ‘Life is changed.’

Marina Abramović, Balkan Baroque 1997, 4-day-and-6-hour performance, 47th Venice Biennale.

In this performance, Abramović sits atop an enormous pile of bloody cow bones, washing them one by one while singing folk songs from her childhood. The title alludes to her war-ravaged home country, the former Yugoslavia.

© Marina Abramović, courtesy the Marina Abramović Archives

Marina Abramović, The Artist is Present 2010, 3-month performance, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

During the course of her major retrospective at MoMA, New York, Abramović performed this 736 1/2-hour static, silent piece, in which she sat immobile in the museum's atrium while spectators were invited to take turns sitting opposite her. She sat opposite a total of 1,545 people.

© Photo: Marco Anelli, courtesy Marina Abranović Archives

Marina Abramović, 7 Minutes of Silence 2016, performance at As One, Athens.

Presented at the Benaki Museum in Athens, this work consisted of the 'Abramović Method' (a series of exercises), newly commissioned performance pieces by Greek artists and an extensive public programme of lectures, workshops, discussions and other participatory events. The largest and most ambitious project dedicated to performance art in Greece to date. As One placed this contemporary art form in the spotlight in order to engage and inspire the Greek public.

© Photo: Panos Kokkinias, courtesy NEON and MAI

Tehching Hsieh lives and works in Brooklyn, USA. Representing Taiwan at the Venice Biennale, Doing Time is at Palazzo delle Prigioni, Venice, 13 May – 26 November. His work One Year Performance 1980–1981 (purchased with funds provided by the Asia Pacific Acquisitions Committee in 2013) will be on display at Tate Modern from 7 August.

Marina Abramović lives and works in New York. Marina Abramović – The Cleaner is at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, 17 June – 22 October.