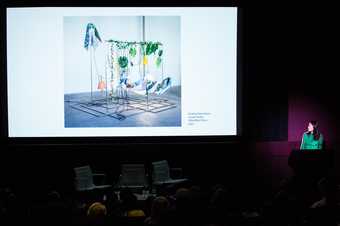

Wenny Teo, Ros Holmes and Monica Merlin on a discussion panel for Gender in Chinese Contemporary Art, Tate Modern, 22 February 2018

© Jacob Perlmutter

Part of the Now programme of contemporary art from China, which features a number of women artists presented by five visual organisations within the Plus Tate network, this symposium was dedicated to a series of scholarly presentations as well as artist talks and discussions around issues of gender and femininity in Chinese contemporary art.

Session one, ‘Critical Framework’, consisted of Dr Monica Merlin’s paper ‘Rethinking Women Artists and Gender in Contemporary Chinese Art’, which offered a critical overview of a history of contemporary art by women in China from the 1970s to now; Dr Ros Holmes’s paper ‘No More Nice Girls: Celebrating the Ugly and the Artless in China’s Online Spaces’, which suggested new ways to think about art production and distribution through the digital and mediated spaces within Chinese practice; and a panel discussion moderated by Dr Wenny Teo.

Starting with Chinese artist Xiao Lu’s 1989 performance work Dialogue – arguably China’s first major feminist contemporary work of art – Monica Merlin criticised the fact that her contemporary male critics have not sufficiently acknowledged the gender and agency of Xiao Lu. This is only one of the many examples of women’s presence and voice being neglected in the male-dominated art world. Driven by a concern for the lack of social, institutional and scholarly attention to the problem of gender throughout the history of Chinese contemporary art, Merlin’s talk reflected on how the making of art history should acknowledge and engage alternative gender narratives beyond the dominant ones. Her paper unpacked and constructed a micro-history for a series of terms and vocabularies such as nüxing (女性 woman) and nüxing yishu (女性艺术 women’s art or feminist art) within the artistic and social context of China. Nüxing yishu emerged as a new category in the 1990s, alongside other trends such as political pop and apartment art. The publication of the artist and curator Xu Hong’s article ‘Walking out of the Abyss: My Feminist Critique’ in 1994 became a manifesto for feminist art criticism in mainland China. The following year saw the opening of an exhibition with a feminist viewpoint curated by Liao Wen, entitled ‘Women’s Approach to Chinese Contemporary Art’, in which she introduced the concepts of subversion and turmoil into art by women. These curatorial and critical voices were some of the many that began, according to Merlin, to ‘emphasise the presence and practice of women, their aesthetic and conceptual concerns, as well as interpretation of their gendered subjectivity, femininity and womanhood’.

In the meantime, women artists started to shift their artistic engagement from conventional forms and mediums to less conventional ones for the sake of expressing their creative subjectivity and female experience. Lin Tianmiao and Yin Xiuzhen started to use their work to explore female subjectivity and play with the prevailing gender codes that circulated on mass media. When discussing Xing Danwen’s nude photographs, arguably the first set of photos of female nudes taken by a woman artist in the PRC, Merlin suggested that the female body became a critical medium and arena for the artists to highlight and perform their gender difference and their experience as women in the 1990s. These reassessments of womanhood had a political dimension during this period. According to Merlin, they have been understood as a subversion of the gender politics implemented during the Maoist era, which ‘tended to neutralise gender difference and femininity for equality’s sake following the mission of so-called state or communist feminism’.

Merlin then argued that if women artists’ creative representation of the female body in mainland China was politically-charged, it could not then be reduced to a mere tool for personal exploration. As she suggested, ‘Representing, displaying and reclaiming the female body are strategies for consolidating women’s political presence, and a tool of their empowerment within the cultural industry and the value-making system. But it is not only the representations of the body – gender is a valuable method for interpretation’.

The turn of the twenty-first century saw an increasing number of women artists using their bodies as performance mediums in experimental art, in contrast to the decline in performance art practices of many male artists who turned instead to more commercial mediums. However, Merlin pointed out the fact that there has been a gender bias in the reception of performance art, as in the case of the unequal critical and public reactions to the naked performances on the Great Wall by woman artist He Chengyao and male artist Ma Liuming.

Unsatisfied with the limitations that came with the term nüxing yishu, Merlin emphasised the potency of presenting works by women artists in a global context, rather than remaining with the archaic category of nüxing yishu. The exhibition curated by Wang Chunchen at the CFCCA in Manchester that featured a group of young women artists might be seen as a crucial step forward. While acknowledging the achievements of the women artists who had responded to socio-political gender issues and challenged stereotypical views about femininity and sexuality, Merlin concluded by insisting on the need for further dialogue to continue to challenge and explore the complexities of making and understanding Chinese contemporary art, especially by listening directly to the voices of practicing women artists from China.

In relation to the peculiar ecology of the Chinese Internet (known as the ‘chinternet’), Ros Holmes examined the ways in which gender and identity were performed, and discussed a series of appropriated yet innovative aesthetic categories such as kitsch, artless and ugliness, in internet works by Miao Ying and Ye Funa. In her paper, Holmes argued that the artists’ creative strategies of humour, appropriation, role playing and the self-conscious celebration of the amateur and the ugly not only parodied China’s narcissistic online culture, but also uncovered the more pernicious facets of the current internet environment and the underlying problems of digital forms of representation.

Before embarking on an analysis of Miao Ying’s and Ye Funa’s works, Holmes introduced the distinct characteristics of the ‘chinternet’ in parallel with the surging interest of media art in China. She suggested that a paradox arose: while media art has been undergoing a dramatic rise in demand for internationalism following China’s economic boom and globalisation, the Chinese Internet has been increasingly penetrated by online censorship, surveillance and the contingencies of political control through an online legislative instrument known as the ‘Great Fire Wall.’ However, the ‘chinternet’ is able to sustain itself, thanks to a vast number of online users who spend a great amount of time on social media, online shopping platforms and live streaming websites that have global features yet distinctly Chinese characteristics (as they are developed by domestic IT companies). As members of the first generation of artists who grew up with mass digital technology, Miao Ying and Ye Funa embraced the language and aesthetic of the internet wholeheartedly, yet their practice contrasted with the slickness of other new media artists by self-consciously taking on low-fi aesthetics and old-school dirt-style websites. By examining Miao and Ye’s anti-aesthetics, Holmes argued that it could be read ‘as an attempt to de-stigmatise preconceptions about China’s online realm by re-asserting the value of vernacular creativity emerging from the world’s largest online community.’ She then proceeded to propose that their embrace of the internet aesthetic was a means to critically respond to sensitive issues of online censorship, and to unravel and destabilise digital representation and the embedded gender expectations of social media and commercial online platforms.

In her analysis of Miao Ying’s work of online poetry Meanwhile…in China, so in Love Will Never Fell Tired Again, Holmes suggested that Ying was constructing parodies of existing cultural issues by means of visual and textual references sourced from cultural stereotypes embedded in simple pictures circulating online. Loaded with absurdity and ridicule, these images emblematise the online attention economy that often thrives on difference and the symbolism Likewise, Lan Love Poem combines images of screenshots from banned websites set against a background photo of a deserted landscape with a Chinglish text that Miao adapted from everyday life in China. Holmes noted that this synthesis seemed to comment on the misconception of China’s internet landscape as nothing but a wasteland abandoned of any meaningful creative expression due to the imposition of censorship. The use of Chinglish poetics in a kitschy style presents a triumphant vision of digital parochialism, and in the meantime effectively critiques the blank formalism of the mainstream media and the increasing professionalisation and standardisation of the global Internet. By relating to the creative tactics that online activists adopted in order to circumvent censorship, Holmes suggested that Miao Ying’s work can be read as asserting the potency that was paradoxically attached to creative constraints: the Internet as a form of psychological conditioning can function as social and cultural self-empowerment.

Playing with the common visual elements that characterise increasingly popularised online live streaming platforms, Ye Funa’s Exhibitionist Peepshow is a participatory online performance programme that playfully examines how social media allows one to perform his or her identity. Preceded by a critique of the immediacy of online platforms including Meipai and Instagram – which register coded systems of gendered beauty and foster a loss in the authenticity of self-portraiture – Holmes showed that by means of subversive role playing, the performances in Peepstream satirised the market for online beautification through an embrace of kitsch – a playful gesture against rule-binding images. On this artistic strategy of role playing, Holmes suggested that due to its inherent fluidity, ‘it can escape the clichés of computer-generated representations, while questioning the relationship between body image and technological subjectivity.’ She further claimed that the performances served to challenge traditional gender binaries through the alternative self-positioning of gender in online representation. She then concluded with an acute observation: ‘with the vicissitude of self-branding, artists often resist or respond with the depiction of the highly flexible, liminal selves’.

Wenny Teo initiated the panel discussion with the question of language. Because of the difficulty of translating the term nüxing yishu into English, Merlin suggested that it had to be understood in relation to its social, cultural and political contingencies, as it carried a different meaning from the category of ‘women’s art’ or ‘feminist art’ in the West. The meaning of nüxing yishu shifted over time in China: it was attached to notions of feminism in the 1990s, but its meaning changed within curatorial practice in later years. On the question of the performativity involved in the linguistic games of the younger artists who inhabit online spaces, Holmes remarked that their adoption of these games was meant to celebrate the vibrant forms of indigenous online interaction, which was characterised by a distinctive linguistic feature and an excess of texts. On the question of whether LGBTQ movement exist in China’s contemporary art practice, Merlin responded by suggesting that Shi Tou was one of the earliest lesbian artists from the Yuanmingyuan circle in the 1990s, and more recently there had been an exhibition entitled DIFFERENCE·GENDER, hosted in 2009, which grappled with questions of diversity, plurality and the multiplicity of gender identity. On the precise way that audience participation works online, Holmes elaborated that Ye Funa’s Peepstream allowed the audience to add comments and to ask the artists to modify the performance in real time, which is a crucial feature of instant interaction that online platforms offer.

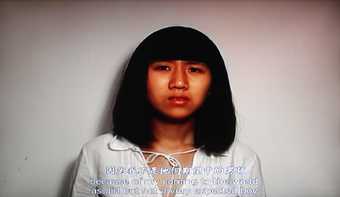

Nabuqi speaking about her work at Gender in Chinese Contemporary Art, Tate Modern, 22 February 2018

© Jacob Perlmutter

Ye Funa speaking about her work at Gender in Chinese Contemporary Art, Tate Modern, 22 February 2018

© Jacob Perlmutter

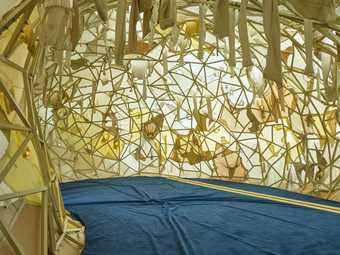

In the second session, ‘Voices of the Now’, Nabuqi began by introducing her work, Floating Narratives, which has been shown in the Now exhibition. This installation piece consists of multiple levels of space, including the physical space of the light and the audience, the two-dimensional space of the images and the space of the narrative as conjured through the inclusion of fake plants and a lemon. Whether literary or material, these spaces form a peculiar relationship to the spectator, who is constantly entangled within the intriguing myth of the real and the unreal. In her autographical video piece No.4 Pingyuanli to No.4 Tianqiaobeili, the artist Ma Qiusha showed how her work was largely built on a gender anxiety that is interwoven with the contradictory push and pull of filial duties and personal freedoms in her complex relationship with her parents. Dealing with memory, emotional experience and dislocation, many of Ma’s video, performance and installation works are indicative of the often difficult intergenerational relationship between the younger post-1980s generation and those who experienced the Cultural Revolution. Memory also served as a medium in Ye Funa’s early work Family Album, in which she reenacted the characters of her mother and grandparents, and incorporated their voices from interviews. For her live streaming performance work Peepstream, Ye elaborated on the fact that the way in which the audience engaged with online performance was fundamentally different from the way in which they participated in a physical gallery space: online platforms enable a large number of people to directly interact with the performers at the same time as each other, which is unlikely to happen in a traditional exhibition. A playful subversion of institutional boundaries was also evident in her previous project Exhibitionist: Curated Nail, where she invited participants to submit their proposals for curating exhibitions on the space of a fingernail. In the panel discussion, the three artists expressed different views about the question of gender and femininity in their art practices. Nabuqi resisted her work being narrowly defined by preexisting categories such as ‘women’s art’, while Ma Qiusha acknowledged the role of femininity and female body in her practice. Without being consciously aware of issues of gender at the beginning of her art-making, Ye Funa later realised that her use of manicures as an art form, as well as her fascination with performance, were both loaded with gender complexities, and predominantly featured female characters.