In the pictorial system of Chinese characters, the word 安, denoting ‘peace’ or ‘safety’, is composed of a female element situated under a roof, or in a dwelling. This suggests a belief within Chinese culture that peace is best secured by the presence of a woman at home. While Chinese is not the only language in which gender stereotypes abound, this example raises the question of whether it is possible for societies to extricate themselves from archaic belief systems about gender and identity that are embedded in an everyday tool as vital as language.

An attempt to provide an insight into the multiplicity of female identities in Chinese culture took place in 2018 in the form of NOW: A Dialogue on Female Chinese Contemporary Artists. This was a programme of exhibitions undertaken by galleries across the UK that looked to celebrate the varied practices of Chinese women artists working today. United under the umbrella theme of gender, the exhibitions were nonetheless individualised to reflect the outreach objectives of their host organisations through strategies of interpretation and display.

Nottingham Contemporary featured the work of Ye Funa (叶甫纳) in a whole-room display titled From Hand to Hand that ran from 24 March to 7 May 2018. Ye’s recent work is typified by visual and aural excess, reflecting the glut of stimuli offered by the internet. The exhibition charted the trajectory of her practice, from the intimacy of the family album in which Ye takes on the guises of each of her relatives, through to video works depicting outlandish characters in garish live-streaming situations, capturing the sensory overload characteristic of this internet phenomenon. Also presented in this show was an imaginary account of a retired table tennis player, played by Ye, in a work that was made up of a video mockumentary and a table of pretend artefacts. This work highlights the cult of celebrity that has now become commonplace in sport, but places special emphasis on China’s identification with ping pong – a game in which all but one of the top ten grand slam players are from that country.

In Manchester, the Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art presented a group display featuring the work of seven younger-generation artists: Nabuqi (娜布其), Wu Chao (吴超), Yang Guangnan (杨光南), Li Shurui (李姝睿), Luo Wei (罗苇), Hu Xiaoyuan (胡晓媛) and Geng Xue (耿雪). This ran from 16 February to 29 April 2018. The selection of works addressed individual subjectivity as expressed through photography and performance, as well as the power of new technology and media, all explored through complex sculptural installations.

From 17 February to 3 June 2018, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA) presented the work of two artists: Ma Qiusha (马秋莎) and Shen Xin (沈莘). Ma’s practice interrogates the concept of filial piety (respect for one’s parents, elders and ancestors) and female roles in China, often with a dark twist. From No.4 Pingyuanli to No.4 Tianqiaobieli 2007, the video work for which Ma is perhaps best known, was displayed in MIMA’s central exhibition hall. It shows Ma speaking directly to the camera, ruminating on the emotional weight of her family’s expectations throughout her formative years. These revelations are visibly difficult for her to recall, but it is only evident at the end of the video precisely why, when she removes a bloodied razor blade from her mouth. In this way, the work elicits a strong psychological response while also addressing the vulnerabilities of the body.

Shen Xin was represented at MIMA by her 2014 film Records of Rites. This video projection reflects on the relationship between Britain and China through footage of the former Mayor of London Boris Johnson’s unrealised ambitions to rebuild the Crystal Palace in London in 2013, which is run alongside historical accounts of Lord Elgin ordering the destruction of Beijing’s Old Summer Palace and its contents in 1860. Despite the fact that Shen narrates these idealistic ventures, there is the sense that she reserves judgment, permitting the pretensions of certain past diplomatic ceremonies, such as that of the Crystal Palace relaunch, to play out by themselves in her film.

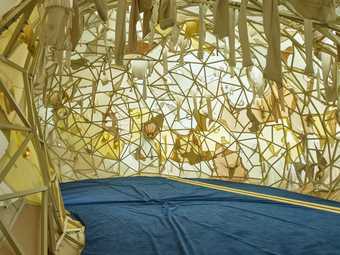

Yin Xiuzhen, Digestive Cavity 2015, installation view, Turner Contemporary, Margate, 2018

Photo: Stephen White

In Margate, Turner Contemporary presented the work of the established artists Yin Xiuzhen (尹秀珍) and Duan Jianyu (段建宇), in an exhibition that ran from 21 February to 2 September 2018. Yin is known internationally for employing used garments to make sculptures that evoke feelings of intimacy and individuality in the face of China’s sprint towards industrialisation. In Margate this was expressed through the work Digestive Cavity 2015, a sculptural installation made from used items of clothing stretched over a metal lattice structure. Part of a series of sculptures of human organs (in this case, the stomach), Yin’s work was offered by the gallery as a ‘place to stop and slow down [and] an antidote to the fast pace of contemporary life’. Visitors were invited to step inside it, without shoes, which only added to the effect of entering into a personal space. Meanwhile, Duan’s paintings revealed the remarkable within seemingly ordinary, everyday scenarios by bringing together the imagery of ancient Chinese mythology with that of present-day popular Chinese culture.

A conference in Tate Modern’s Starr Cinema, Gender in Chinese Contemporary Art, took place on 22 February 2018, in the opening week of three of the exhibitions. Many of the exhibiting artists attended, with some participating in panel discussions and giving talks that offered insights into their practice. In addition, HOME in Manchester programmed a series of short films by Chinese women artists across two evenings in February and March, with a particular focus on subjective responses to societal shifts in China in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Such a bold undertaking – shared by these organisations up and down the country – begs the question: what were British audiences able to learn about art made by Chinese contemporary women artists? One might suggest that NOW succeeded in showing that the output of these artists is varied and ambitious, particularly in the medium of the moving image and in the way that the artists address the wider effects of new technology. Yet the more crucial question might be: why has it taken quite so long for these artists to be shown in the UK, and in such a programmatic way? Many of them have already enjoyed significant attention in China and elsewhere in Europe. So, while one accomplishment of this initiative was to assert that art by women can be complex and diverse, another has been to bring a rich range of works by Chinese women artists to a larger audience across Britain.