A little over a decade after French artist Yves Klein’s death, Tate Gallery hosted the first British retrospective of his body of work.1 Originally designed to be a three-person exhibition, including Piero Manzoni and Joseph Beuys, the exhibition was then condensed into a comparative show of Klein and Manzoni’s work, before the curators Jacques Caumont and Germano Celant ultimately decided to mount two separate, but linked, exhibitions at Tate. Michael Compton, then Keeper of Exhibitions and Education Department, acted as the link between the two halves of Two European Artists, liaising with the curators, members of the artists’ families, and collectors from across Europe.

Klein’s section of the show was curated by Caumont, later a noted Duchamp scholar, who was able to rely primarily on loans of Klein’s work from his widow, artist Routraut Klein-Moquay, who also supplied information and documents that accompanied the artworks. Aware of Klein’s influence on other artists, and his prominence within Nouveau réalisme, Caumont sought to present the breadth of Klein’s practice from his relatively short career. Accompanying the exhibition, Caumont, aided by Jennifer Gough-Cooper, put together an extensive chronology of Klein’s life and works, detailing influences on his practice, his key exhibitions, and his intersection with other artists, including Manzoni. This became central to the exhibition catalogue, and these prototype chronologies are now housed in Tate’s Archive.

While Klein’s practice had been expansive in both medium and message and had included performances and events, Caumont focused Klein’s section of the exhibition primarily on the objects he had created throughout his career. Some, such as the IKB series, were paintings done by the artist himself; these were a series of near-identical blue square paintings, so titled because of the use of his trademark Yves Klein Blue paint. Caumont also included paintings made as a result of Klein’s performance-based events, the Anthropométries. One of this series of works was made in 1960, in front of an invited audience, all dressed in formal black-tie attire. As the audience sat around the edge of a large square of paper laid on the floor, and draped across a back wall, Klein had a group of naked women cover themselves in his trademark blue paint and use their bodies to apply it to the paper. They did so either in a standing position, by pressing their bodies onto the walls, leaving an imprint on the paper, or by rolling – or on occasion being dragged – around the paper laid on the floors. This was accompanied by the ‘Monochrome Symphony’, composed by Klein, which consisted of one note played by all the instruments in a ten-piece orchestra. The contrast between the formality and convention of the setting, the audience, and the music, with the contemporary nature of the art making and the aspects of performance involved, indicated a crucial element of Klein’s work: the use of the traditional medium of painting in a radically contemporary way. The resulting works, shown in the Two European Artists exhibition, were displayed as traditional paintings, without context or explanation of the particular creative actions behind them.

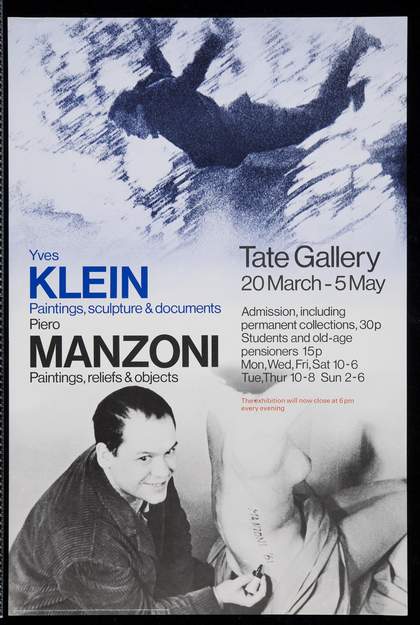

Caumont’s exhibition, while itself fairly conventional in choosing to portray the work of the artist predominantly through his art objects, deviated from the norm through the presence of a wealth of documents, which Caumont included in order to expose the ‘activities’ of the artist, the processes through which he worked. Compton, while trying to persuade a collector to loan a number of documents for the exhibition, suggested that the exhibition’s aim was to ‘try to present his [Klein’s] activities and life-style as vividly as possible’.2 Perhaps the most notable ‘document’ included within the exhibition was a copy of ‘Dimanche’, a newspaper mocked up by Klein on 27 November 1960, and distributed through Parisian newsstands. The newspaper, made to look like a traditional Parisian broadsheet, included a reproduction of Klein’s work Leap into the Void, a photographic document created in collaboration with Harry Shunk and János Kender, which appeared to show Klein leaping recklessly from the top floor of a house to the street below. In reality, the photograph was a composite of two images, one in which Klein leapt from the house onto a sheet held by his accomplices below, and another photograph of the empty street.3 The images were spliced together, to create the illusion of free-fall. Photographs of Klein practicing judo, of which he was a master, and images of the creation of the Anthropométries were also included in the documents on display, as was an image of Klein reading a copy of ‘Dimanche’, flanked by the Eiffel Tower.

Caumont’s and Compton’s aim in exhibiting the documents and artworks separately, but within the overall frame of the exhibition, was to create a total portrait of Klein’s life, demonstrating the ties between all his activities. In a letter to Mme Klein-Moquay, Compton tried to assuage her fears that the documents would make the paintings look falsely academic by suggesting that ‘we would expect them rather to reveal the remarkable character of the artist himself and of the variety and originality of his artistic activities’.4

Allowing the photographic documents to add context to the creation of Klein’s works, allowed the curators to demonstrate those elements of Klein’s objects that were rooted in acts of performance. Given that the intersection between visual art and the explicit act of performance was still a recent phenomenon in 1974, and the increasingly complex notion of what constituted an artwork – object or event – bringing Klein’s performance-based actions to the visitors’ attention offered a unique perspective on the act of art-making. Caumont and Compton considered Klein’s process to be as important as his products, positioning performance not only as a medium but also as a way of making.

Acatia Finbow

July 2016