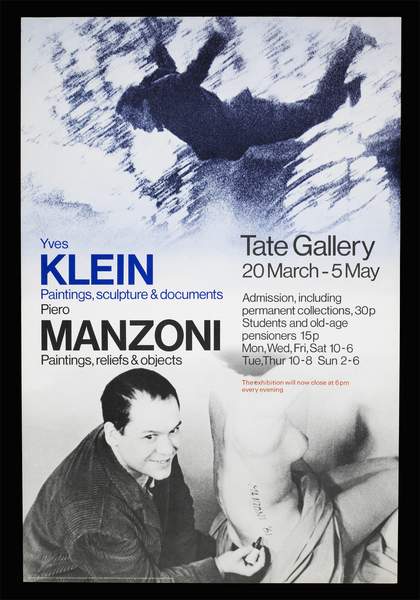

Tate’s 1974 exhibition Two European Artists was reported as the first significant display of Italian artist Piero Manzoni’s work in England.1 Conceived initially as a three-man exhibition, with Yves Klein and Joseph Beuys, Tate eventually settled on two separate, but connected, displays of works by Klein and Manzoni. Curator and critic Germano Celant curated the Manzoni exhibition, which presented work from the artist’s short but prolific career. Tate’s pioneering Keeper of Exhibitions and Education, Michael Compton, oversaw the joint exhibition. Compton provided a bridge between the two organisers, and often liaised with collectors and supporters of Manzoni’s work, including Manzoni’s mother Contessa Valeria Manzoni. Celant’s key concern in his role as curator was to amass examples of not only Manzoni’s sculptural works but also of his photographs and documents that showed the artist’s activities. During the planning of the exhibition, Celant wrote to Compton, saying, ‘You have to consider that the show will concern all the activity of Manzoni, so it will be done of paintings, cans, lines and photographs documenting his activity. I think that works and documentation will give to the show an exciting image.’2

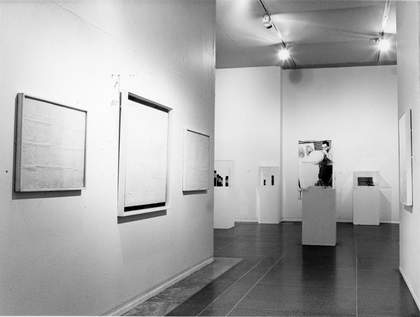

The aim of Celant’s exhibition was not only to show the final sculptural objects Manzoni had created but also his way of working. To do so Celant presented two key elements of Manzoni’s works: his white paintings known as Achromes and a variety of his action-based conceptual sculptures. The Achromes were an ongoing series of works, begun at the end of the 1950s as paintings which presented white canvases covered with paint, glue and white clay. As the series progressed, Manzoni creates the white squares using other materials, such as feathers, glass fibre, and bread rolls. Celant selected a number of these Achromes in different materials for display at Tate, demonstrating Manzoni’s changing material process over time. Alongside these, Celant also showed a number of Manzoni’s sculptures, which utilised performance and action as integral characteristics. These included Artist’s Breath, balloons filled by the artist exhaling, Lines, rolls of paper on which the artist had drawn continuous lines of varying length which were then rolled and kept in tubes, and Egg with Thumbprint, boiled eggs onto which the artist had inked his thumbprint and which were presented in cushioned boxes. The sculptures were linked by their use of everyday objects, which were signed or marked in some way by the artist, thus elevating them to the status of artwork. To illustrate the artist’s hand within the work, Celant selected seven documentary photographs of the artist ‘doing’ the works, had them enlarged, and presented them next to the resulting sculptures in the exhibition. The enlarged photographs, gathered from various Manzoni collectors, acted as illustrations for Manzoni’s creative process.

While presenting the sculptures as stand-alone objects would have allowed the exhibition visitors a thorough survey of Manzoni’s oeuvre, the inclusion of the seven photographs, six of which were captioned from the first person perspective ‘I prepared …’ ‘I carried out …’ made the artist’s process explicit.3

Rather than simply being found objects – an egg, a balloon – transformed into artworks by their selection by the artist and their subsequent presence in the museum, the sculptures were presented unambiguously as the result of the artist’s process of alteration and marking; the materials were presented by Celant as less significant than the processes that had transformed their state. Since each of the sculptures presented was one in an edition, the photographs were not used to illustrate the creation of one specific object but to make present the artist’s actions in relation to the series as a whole. Showing those actions as they happened, the photographs made clear the transformative performance, capturing the moment of action undertaken by Manzoni to mark the objects – eggs, paper, even people – as sculptures. Unlike the parallel Klein exhibition, where clear delineation was made between the objects and the documents, Celant chose to integrate the two more closely. The direct juxtaposition of action and product allowed the visitors the opportunity not just to observe Manzoni’s objects but also to understand his work as driven by process, rather than product. By choosing not to privilege the artworks over the artistic work, Celant made present the artist’s oeuvre not just as a set of objects but also as a process through which those objects were created and designated as works of art.

Acatia Finbow

July 2016