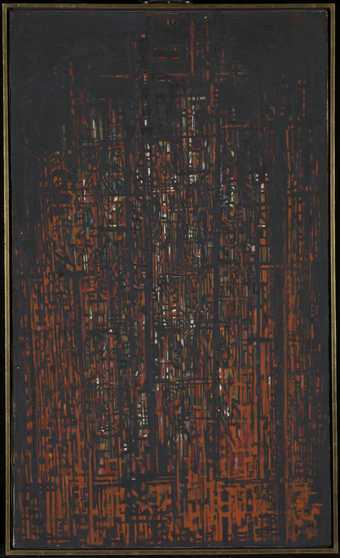

Fig.1

Norman Lewis

Cathedral 1950

Tate L03741

© Estate of Norman W. Lewis; courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

For several years between 2006 and 2015, Nigel Freeman, director of the African American Fine Art department at Swann Auction Galleries in New York, searched for Norman Lewis’s painting Cathedral 1950 (fig.1). It had been exhibited at the 1956 Venice Biennale, where Lewis and Jacob Lawrence became the first two African Americans ever to be shown at the event since it was founded in 1895. Because of the significance of Cathedral in Lewis’s oeuvre and in the context of post-war American painting, locating this painting was important to the history of American art, modernism and African American art and culture. Here Freeman discusses how he finally tracked down Cathedral, his first encounter with it, and the new market for African American art in auction houses in the United States that emerged at this time.

Andrianna Campbell: When did you begin the search for Norman Lewis’s Cathedral? How did you come to know the painting?

Nigel Freeman: We’re now in our tenth year of auctions at Swann selling works by Norman Lewis. As I started to handle his work and fill out and flesh out his career, there was always this line, this mention of his having shown at the Venice Biennale of 1956. I spoke to [Lewis’s dealer] Bill Hodges, but he never said what painting [was shown there]. I did manage to find, on Amazon, an old copy of the Venice Biennale programme curated by Katharine Kuh, who was a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Andrianna Campbell: What was it like finding the programme?

Nigel Freeman: It was many years ago, and I was elated to find a copy and in it there was a picture of Cathedral. It was in black and white but luckily it was photographed. This is unusual because often in these brochures and pamphlets from the 1940s and 1950s, you just get a checklist and there’s no image. I knew immediately that I had seen that picture before.

Andrianna Campbell: Where had you seen it?

Nigel Freeman: Well, there’s a very small image of this Norman Lewis painting in Cedric Dover’s American Negro Art, which was printed in 1960. It’s a tiny, high contrast black and white picture; it’s the size of a postage stamp and must have been submitted by the Willard Gallery, New York, at the time, just as a representative work of the artist. It didn’t mention the Venice Biennale. It simply states Norman Lewis, Cathedral, Art Institute of Chicago. So then I was able to say, ‘It is interesting to know that that was the same painting’. He painted it in 1950, and it was still in the gallery inventory in 1960 so they published it.

Andrianna Campbell: Did you set out to try and discover where the painting was?

Nigel Freeman: Definitely, but we were working on consignments back then [works brought to the auction house and left there to be sold] and people didn’t know work as they do today after Ruth Fine’s show [in 2015].1 Let’s see, this was in the autumn and winter of 2014. A year later I received an email from an attorney that was an estate. This family member had a connection to the Willard Gallery and owned several paintings that were in this estate with Willard Gallery labels, and two works were by Norman Lewis. A work on paper and an oil painting. They were a New York family who had retired to Vermont. It had been in this Vermont family for quite some time, so they didn’t really know much about the painting. As soon as I got the email, I saw it was Cathedral and it was in colour. The email came after years of wondering what happened to the work so it was very exciting.

Andrianna Campbell: How did the family come to own the work through Willard?

Nigel Freeman: It’s unusual, actually. Even though Lewis was represented by the Willard Gallery, the majority of the works that we handle were not actually purchased from them, which speaks of his financial struggles working as a teacher, a taxi driver and a cook. Most of the works that we encounter he actually gave to friends, artists and lovers. Not many well-heeled people walked into the Willard Gallery and bought his work. (Some of Lewis’s paintings were bought by the Rockefellers, and others by Edward Root, but this was rare.)

Andrianna Campbell: And yet all the paintings were fastidiously marked in a ledger and labelled.

Nigel Freeman: Sometimes there’s a Willard Gallery label on the back of a painting but that doesn’t necessarily mean the work was bought there. In addition to many of his gifts out of his studio, unsold artworks that were consigned to the gallery were also returned to the artist. In this case there was a firm connection to Marian Willard because they had other works purchased from her.

Andrianna Campbell: What was the process of going to look at the painting?

Nigel Freeman: I was trying to get the painting into our April 2015 auction but all the family members had to agree. By the time I got the final OK, I drove up to Vermont in a snowstorm to get the painting. It was an additional adventure for me, it was late January I think, and I knew it was snowing that weekend, so I rented a four-wheel-drive SUV and drove up there, and sure enough, I got up there and I was snowed in. I spent the night in Burlington, and got the painting first thing in the morning and drove back.

Andrianna Campbell: There are rumours that the painting was being stored in a barn. Many of Lewis’s works suffered some form of damage because family members, thinking that they had no value, rolled them or placed them in non-climate-controlled settings. Where was this one found?

Nigel Freeman: It was forgotten in an attic in the house. There was a tremendous amount of artwork stored in their house because it was a New York family who had a Vermont house and the children didn’t necessarily go up there as much. For them, it was really a discovery.

Andrianna Campbell: Did the children ever remember the painting?

Nigel Freeman: Oh yes. This work had been in the house, it had been on the wall and they remembered it growing up ... but they didn’t know much about Norman Lewis or who he was until they had to deal with the distribution of their property.

Andrianna Campbell: What was it like to finally see it in Vermont?

Nigel Freeman: You know, we are an auction house so it is rare that we get the same credit as a museum does, but back when we started doing this you couldn’t find Lewis’s work on the internet. Maybe you could see that magenta and yellow painting Untitled c.1960–4 on the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston’s website.2

Andrianna Campbell: Yes, when I started working on Lewis in 2011 few art historians knew his name. You could find the painting at the MFA and maybe the one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and a few others on Bill Hodges’s website.

Nigel Freeman: So finding the painting was a nice closing of the chapter for me, just to find out where it was. [Venice] was such a significant exhibition for the artist and to have a painting like that, to not know where it was, I think, was really unfortunate. Besides group shows in New York at the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Venice Biennale was one of the few really non-commercial shows that Lewis had. (Of course another one being at the Carnegie International.)3

Fig.2

Norman Lewis

Migrating Birds 1953

Collection of Halley K. Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld

© Estate of Norman W. Lewis; courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Andrianna Campbell: Of course, originally called the Pittsburgh International, where he showed Migrating Birds 1953 (fig.2) in 1955.

Nigel Freeman: Yes, Migrating Birds, that had been lost because no-one knew where it was. Now that Lewis’s paintings have value and Google searches produce results you can see that it sold in a Christie’s interiors sale in the 1990s. It was sold for a few thousand dollars alongside Louis Vuitton trunks and things like that.

Andrianna Campbell: Really?

Nigel Freeman: Yes, it’s very sad. It was stuck in an interiors sale in the 1990s, which speaks to how, unfortunately, Norman Lewis’s history and his place in the art world were really sidelined from the main discourse. Thankfully someone who knew bought it and it was in his retrospective [Ruth Fine’s 2015 exhibition], of course. It’s just part of this effort to rehabilitate his history, his career, put him back in his proper place among his peers of that New York School.

Andrianna Campbell: You started doing this work ten years ago, you said, and I was wondering: at that point, what was the interest in dealing with the work? Because there was really very little reason to do so.

Nigel Freeman: Well, I founded this department at Swann Galleries. There wasn’t a department devoted to African American art. Many of these artists who I revered had been undervalued, under-represented and thus the work was often mishandled or even destroyed. Galleries and dealers were selling these works privately but the auction world was completely ignorant of the place of these artists in history.

Andrianna Campbell: What was it like assigning a monetary value to these works, some of which did not even sell in the artist’s lifetime?

Nigel Freeman: There were no auction records, so these artists had no value and the art world had basically stopped including African Americans with the notable exceptions of Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence and maybe Henry Ossawa Tanner. African American artists were prized by some African American families but few works came to auction, and there was no strong collector base.

Andrianna Campbell: How did you know these works?

Nigel Freeman: My wife owned A History of African-American Artists by Harry Henderson and Romare Bearden.4 She had had it as a college student because it was a gift from her aunt. I always leafed through it because I was struck by the quality of the work.

Andrianna Campbell: So there was a separate history that was largely kept alive by African American critics, scholars and artists?

Nigel Freeman: Bearden and Henderson’s was the first general text on African American artists. Henderson also had a wonderful collection of works by Bearden. At the time, in 2003–4, Ruth Fine had just organised her Bearden show at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. You know Bearden did abstract paintings in the late 1950s and early 1960s as well.

Andrianna Campbell: Yes, he showed at the Kootz Gallery in New York in the late 1940s.

Nigel Freeman: So we had those, and a group of works on paper, and I was able to get other consignments of works by Hale Woodruff and Lois Mailou Jones so we had a really great section of African American art. It was the first time someone had deliberately organised this kind of material and I wanted to contextualise it. So we placed these with modern artists like Pablo Picasso and Henry Moore, in the context of modernism, and it did very well. The Beardens, the two collages sold for over $100,000; that was the first time that had happened to Bearden. Of course, that gets people’s attention and we actually were fortunate enough to do it. We did this in the autumn of 2005 and then I did a similar sale in the spring of 2006. Now, collectors call us about consigning, so we really knew that there was going to be a great market for this material and so we launched the department in the autumn of 2006 and we’ve been doing sales since February of 2007.

Andrianna Campbell: That is very interesting because now there is so much discussion about the market for these works and often (and I am guilty of this) it is noted that the market is not good. But I wonder if all of these museums would consider buying a Lewis or restoring one if the market wasn’t strengthening.

Returning to Cathedral, it was shown in the Venice exhibition tilted American Artists Paint the City, alongside works such as Willem de Kooning’s Gotham News 1955 (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, New York). We know Kuh named that painting but she didn’t title Franz Kline’s New York, N.Y. 1953 (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, New York).5 It seems so many of Lewis’s works make reference to the landscape or the city, whether it’s Harlem Turns White 1955 (private collection) or the aforementioned Migrating Birds. Have you noticed this in the works you’ve handled?

Nigel Freeman: As you mentioned there are certainly urban references in that early work from the late 1940s and the 1950s, at times overt ones to something that’s spiritual. Yeah, absolutely, one could ... it’d be tempting to draw connections to Lyonel Feininger.6

Andrianna Campbell: The American city is something of an obsession in the twentieth century. I mean, Marcel Duchamp writes of it and so do many others. Chicago is the birthplace of the skyscraper and the modern office building. American architect Louis Sullivan’s edict ‘form follows function’ – do you think that inspired Kuh’s choice for a theme?7

Nigel Freeman: I did go to the Art Institute [of Chicago] and did some more research on Cathedral, and there were a number of letters between Marian Willard and Katharine Kuh … mainly registrarial information with just a reference to the painting’s title. I wanted to be sure that the painting did go to the exhibition that was held in Chicago afterwards, which it did. Because that was an abbreviated version of the Venice show, I wanted to confirm it was shown at the Art Institute.

Andrianna Campbell: I think it is notable that Kuh brings Cathedral to Chicago.

Nigel Freeman: Yes, it is an historic painting. Finding Cathedral after all these years of looking, was really finding one of the missing links in Lewis’s career. For artists such as Lewis, important artists, it has been a team effort of families, scholars, galleries and now museums and auction houses to recuperate their careers.