Critics, scholars and public audiences alike recognise that Barnett Newman’s body of work comprises some of the most challenging examples of abstract art produced in the twentieth century. Still, it is often the case that commentators – whether academic specialists or general enthusiasts – are hard pressed to articulate just exactly how and why particular works reward our attention and reflection. Judging by typical responses to it, for instance, a canvas such as Adam 1951, 1952 (Tate T01091) initially seems to outstrip our capacity to discuss it. The abstract image positively eludes description – the first step in assessing and evaluating the significance of a cultural artefact. But does Adam’s resistance to analysis imply that its meaning is beyond our comprehension? We might be excused for thinking so: as Newman admitted, he considered his art to be ‘metaphysical’.1 At the same time, the artist was committed to the communicative power of his art. He asserted: ‘It’s human scale that counts, and the only way you can achieve human scale is by content.’2 Still, when encountering instances of rigorous abstraction such as that exemplified by Adam, our interpretative procedures with regard to human content are challenged by the absence of the human figure. In this essay, I suggest that Newman implicitly addressed the conundrum through what we might call a displacement of the ‘iconography’ of the human figure to an adjunct medium: namely self-portrait photography. In doing so, he laid the groundwork for an approach to the putative absence of the human figure from Adam, and from his works more generally.

Projection

Fig.1

Hans Namuth

Barnett Newman in front of Be I at his exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, 1950

© Hans Namuth Ltd, New York

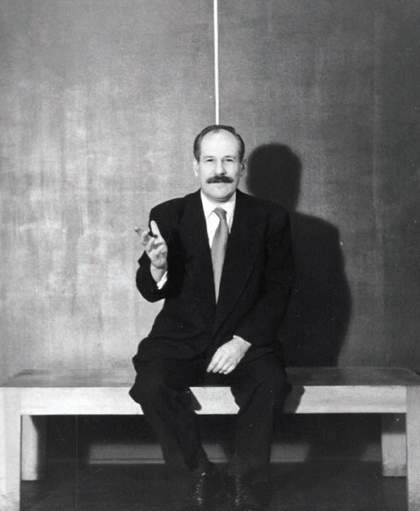

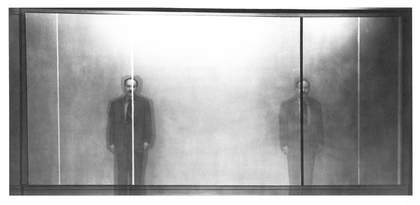

Consider in this regard a 1950 portrait of Newman taken on the occasion of his first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York by the photographer Hans Namuth (fig.1). Newman sits on a plain wooden bench in front of Be I 1949 (Menil Collection, Houston), an expansive red oil painting bisected by a brilliant white zip. The limits of the canvas are not visible, so the painting fills the entire frame. The painter addresses himself directly to the viewer with a steady gaze and a conspicuous hand gesture. Bright illumination, likely from the camera’s flash, casts his stark shadow dramatically upon the canvas surface. The portrait is obviously staged. Not only do other photographs of the gallery suggest that the bench – normally positioned just inside the entrance – was strategically placed in front of the work, but Newman’s striking pose conveys an impression of immobility that is not merely a consequence of the camera’s instantaneous capture. Namuth represents Newman as a statue, an orator carved out of stone. The static symmetry of the photographic image is reinforced by the vertical compositional line that pins Newman’s body to the horizontal bench from which he seems poised to declare his revelations. At the same time, the bisection of Be I by its white zip has the effect of making the painting appear as a kind of diptych, a conventional form for religious altarpieces. The line virtually divides the work into two panels that we can imagine as hinged at the middle, or else sections it into two slabs or tablets. My choice of terms steers the description to a by now obvious conclusion: in Namuth’s portrait, Newman assumes the role of an Old Testament prophet, covenant in voice and hand.3

Portraits of Newman – always made in close collaboration with photographers whom he trusted – provide a unique form of evidence for adducing his intentions. The artist skilfully managed his self-presentation, working with his portraitists to record specific encounters between himself and his paintings.4 In contrast to the widely circulated images of Jackson Pollock at work, Newman never allowed himself to be pictured in the act of painting, but preferred to show himself in conspicuously staged relationships to finished works. (Recall the well-known instance discussed elsewhere in this In Focus, when Newman re-created the picture of the viewers standing close to Vir Heroicus Sublimis 1950, 1951, Museum of Modern Art, New York.5 ) Art historian Wouter Davidts captures the gist of the significance that such pictures have for our understanding of Newman’s meaning by considering them to be ‘critical arguments sanctioned by the artist’, on a par with his writings, and in need of interpretation.6 That task extended to the artist himself. Newman studied his portraits, searching the images – perhaps even years after they were taken – for insights he might gather about his paintings, the embodiments of his creative acts. In a note to Alexander Liberman, who took pictures of Newman in the late 1960s, he wrote: ‘[Your] photos are a revelation to me. The secret of photography is in the sympathy the sitter has for the photographer.’7 The statement reverses conventional expectations: it is not the photographer’s sympathy for his subject which will produce an exceptional picture, but rather the subject’s sympathy for the portraitist – the sitter’s willingness to share through a representation not just his likeness, but also his personality, himself.

Incorporation

Fig.2

William Vandivert

Barnett Newman in his Front Street studio with Adam (left), Eve (centre) and Horizon Light (right), early 1950s

© Estate of William Vandivert

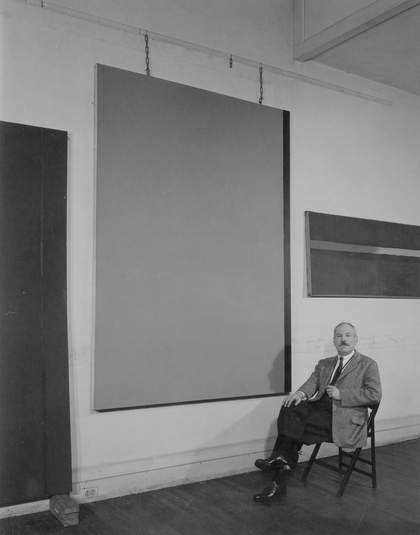

Newman’s openness to relationship appears palpable in a striking portrait William Vandivert made in the early 1950s of the artist posing with Adam and Eve 1950 (Tate T03081) (fig.2). Newman wears a sports coat and tie, highly polished shoes and his trademark monocle; he steadies himself by resting a hand securely on his crossed knee, while fingering the eye glass with the other. Although he sits on a simple wooden folding chair in a sparsely appointed studio, Newman’s dressy attire and composure suggests the kind of ritual formality we have already seen in his portrait as an orator in front of Be I. As in Namuth’s picture, here he is serious, but not humourless. Besides the sitter, the photograph mainly features Eve, the only painting we see in its entirety. Hanging above him is Horizon Light 1949 (Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, Nebraska); Adam is propped up on bricks against the studio wall next to Eve.8 What I have not yet remarked on is the odd, but clearly deliberate, decision (on the part of the artist or the photographer, or both in collaboration) to project Newman’s profile in silhouette precisely against the lower right corner of Eve. That cast shadow puts the image of a man’s head at the intersection of Eve’s framing edges, exactly where the vertical zip meets, and notionally crosses, the horizontal bar that defines the actual limit of the canvas. In other words, there is a ‘skull’ at the base of the painting. In light of my discussion of Vir Heroicus Sublimis elsewhere in this project, the speculative claim implicit in my description becomes plain: Vandivert’s photograph harbours something like the iconography of Adamic typology.9 At the same time, it strains credulity to think that Newman and his portraitist consciously set out to replicate such a visual trope. Perhaps a more general claim can be advanced: eliminated from Newman’s resolutely abstract paintings, explicit references to the human figure have, in this picture and others, reappeared.

Fig.3

Hans Namuth

Barnett Newman with Onement II (left), Eve (centre) and Joshua (right) at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, 1951

© Hans Namuth Ltd, New York

Fig.4

Plan of the layout of Newman’s solo exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, 1951

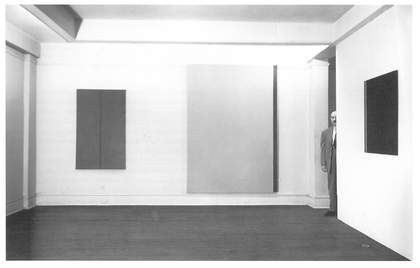

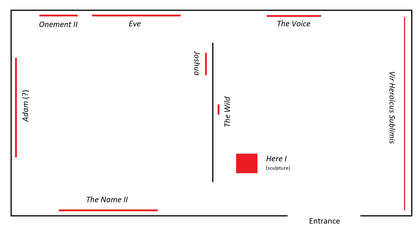

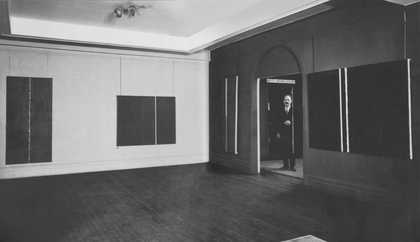

Consider another premeditated picture of Newman with Adam and Eve, again taken by Namuth. The view shows Eve installed at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1951, next to Onement II 1948 (fig.3). On the adjacent wall hangs Joshua 1950 (private collection), titled after the Old Testament figure who led the Israelite tribes after the death of Moses. We know that Adam, although not visible, was installed across from Joshua on the opposite wall (for a plan see fig.4). Also present by implication is The Name II 1950 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), a 264.2 by 240 centimetre canvas of white oil and acrylic paint with four slender white bands. It was hanging on the wall across from Eve, and therefore Newman is facing The Name II as he looks at Namuth’s camera – which is to say that, in the photograph, we see the artist and three of his paintings from the reverse point of view of another one. The structure of beholding instituted by Namuth’s shot, which encourages the viewer to adopt the camera’s point of view, necessarily involves us in the dialogue taking place within and among Newman’s works, quasi-entities that they are. Compositionally, Newman is shunted considerably stage left (our right); his standpoint recapitulates the extremely off-centre zips in both Eve and Joshua (not to mention Joshua’s noticeable off-centre hanging on the central wall). Peeking out from behind the central wall that divides the gallery, the painter is bisected by its edge: the splitting formally echoes the bilateral division of Onement II by its central band. In other words, Newman and Namuth stage an image within which the artist’s body assumes and mirrors certain features and aspects of his paintings, constituted as they are by conspicuous verticals, bisection, lateral displacement and points of view. The photograph virtually incorporates Newman into the fictional orders his paintings create.

Fig.5

Hans Namuth

Double-exposed photograph of Newman with Vir Heroicus Sublimis at Betty Parsons Gallery, 1951

© Hans Namuth Ltd, New York

Fig.6

Aaron Siskind

Double-exposed photograph of Newman with (left to right) Onement III 1949, Covenant 1949, Horizon Light and The Promise 1949 at his exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, 1950

© Aaron Siskind Foundation

The belief that Newman’s zips are stand-ins for human figures is common. In 1951 Namuth made a double-exposure on film to clone Newman and project his duplicate bodies directly onto the bands of Vir Heroicus Sublimis (fig.5). Photographer Aaron Siskind made a comparable analogy the prior year: through a semi-transparent Newman, the viewer glimpses the inside edge of an open door (fig.6). Because the linear dimension of the edge resembles some of the zips contained by the works flanking the painter, it helps establish a formal rhythm of verticals across the photograph’s transparent picture plane, binding Newman’s body to the sequence. Indeed, it is possible to see the entire cased opening of the doorway – just beyond which Newman stands at the threshold of the gallery – as shaping out dimensions akin to those of the paintings on either side. The effect is that the opening itself takes on the appearance of a painting within which Newman stands (observe that the white jamb of the casing functions as yet another zip).

Fig.7

Aaron Siskind

Installation view of Concord and Tundra at Newman’s exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, 1950

© Aaron Siskind Foundation

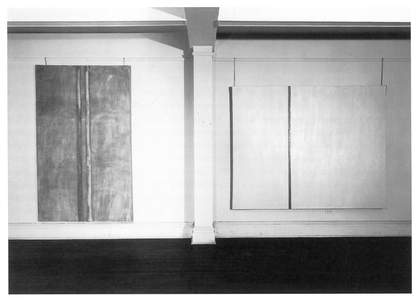

Not only do such photographs propose the imbrication of figuration and abstraction as the embodied content of Newman’s art, they also reveal interconnections between one work and another. A second photograph by Siskind bears on the relation of Concord 1949 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), which was in the 1950 Betty Parsons show, to Eve, which was in the next year’s show. It pictures the double-zipped Concord hanging next to the single-banded Tundra 1950 (private collection) (fig.7). At the time, the central wall that appears in Namuth’s 1951 gallery image had not yet been installed. When it was constructed, it stood perpendicular to the square pilaster between Concord and Tundra. Comparing the two photographs reveals that in 1951, Eve was installed in the exact location that Concord had been in the previous year.10 Given that the word ‘concord’ likely refers to the state of harmony and grace that was annulled by Adam and Eve’s participation in original sin, the placement of the paintings – occupying the same position in the gallery in sequential years – seems attributable to more than just chance.11 Did Newman suddenly realise that Concord’s wall had been divided, as the Garden of Eden had been divided from human achievement, and decide in a moment of inspiration to put Eve at the scene?12

Destruction

We might understand Newman’s calculated use of photography to frame himself in particular relationship to his works as a compensatory gesture. For an artist and thinker who insisted on the profoundly human content of his art, the absence of the human figure – the self-imposed prohibition against exploiting the image of the human body to narrate the compromised ‘legend[s] [and] myth[s] … that have been the devices of Western European painting’ – must have been a poignantly felt injunction.13 Moreover, in the face of an often dismissive critical landscape, where commentators routinely failed to grasp the principled interdependence of Newman’s human content and the modes of pictorial address he instituted in his abstract paintings, supplementary discourses could light the way. In essays, interviews and photography, Newman found vehicles within which he could proclaim and defend his commitment to the persistence of the ‘figure’, to the totality of human being, even as it faced immense peril. It is not insignificant that Newman’s frequent invocation of human scale, the sensation of time and the feeling of place – that is, the fundamental dimensions of embodied experience – took place during a time of unprecedented human violence, in which threats against the integrity of the body were realised in horrific form: witness the magnitude of the systematic murder of six million Jews during the Holocaust; the casualties of the Second World War, which numbered fifty to eighty million; and the incineration of countless human bodies by the explosion of two atomic bombs dropped by the United States on Japan (the intense blast of which seared darkened silhouettes of its victims onto the walls of buildings – an association that renders the iconography of Newman’s cast shadows all the more charged).14 The crisis of the body to which Newman was exposed was a real one, and the crisis of the figure in painting was more than an analogy for it. The crisis of the figure in painting involved the fundamental possibility of personhood, of human being.15

Newman articulated the existential, if not the ontological, conditions of his art and its historical situation by contrast. In ‘Surrealism and the War’, an unpublished essay he wrote in March 1945 – just as the gruesome photographs of emaciated victims of the Nazi extermination camps were reaching New York – the artist attempted to explain the consequences of the art world’s failure to grasp the ‘prophetic’ nature of the surrealist project of the 1920s.16 The movement’s seemingly pathological subject matter, he argued, was far more connected to its historical situation – and to possibilities of human violence that were realised during the First World War – than the ‘antirealist program of modern art’. He praised surrealism for its ‘revival of subject matter’, for reintroducing the possibility of art concerned with human content:

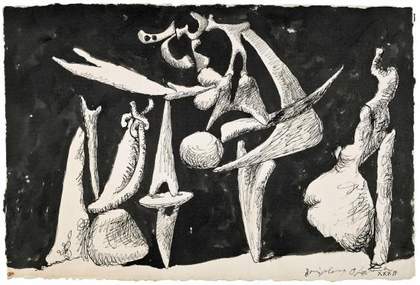

No painting exists [that is better surrealism] than the photographs of German atrocities. The heaps of skulls are the reality of [their] vision. The mass of bone piles are the reality of Picasso’s bone compositions, of his sculpture … The broken architecture, the rubble, the grotesque bodies are the surrealist reality. The sadism in those pictures, the horror and the pathos are around us … Those who saw surrealist works as the esoteric playthings of decadent sophisticates, removed from life, cannot avoid the fact now that these things were the ‘super-real’ mirror of the world to come, of the world of today.17

Fig.8

Pablo Picasso

The Crucifixion 1932

Musée Picasso, Paris

Succession Picasso/DACS

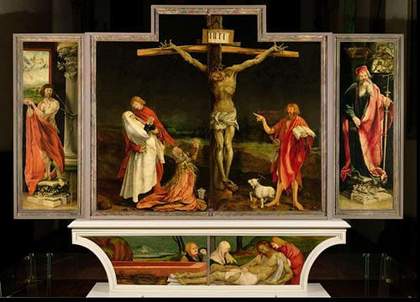

Ironically, perhaps, some of the pictures to which Newman likely refers are those by the surrealist artist Lee Miller, one of the first photographers after the war to document for Life magazine the criminal violence of the Nazi death camps. And Newman’s reference to Picasso’s bone compositions likely point to the Spanish artist’s surrealist-inspired works from the early 1930s, including those reproduced in the first number of the surrealist periodical Minotaure, published in 1933 (such as the closely related image from the series seen in fig.8).18 In that issue, eight recent pen and ink studies by Picasso of the Crucifixion cover a section of three pages. In four of them, he renders the body of Christ as a stack of bones or bone-like forms, tenuously balanced in towering piles and configured in a cruciform shape. On the main two-page spread, a pair of crosses – scaled relatively large on the page and showing a solitary Christ with giant mandibles – bracket four smaller, sketchy compositions that depict, with various degrees of abstraction, secondary figures at the foot of the cross and to each side. (A related watercolour was reproduced in Herbert Read’s 1936 survey, Surrealism, which Newman owned.)19 Turning the page reveals two more fully realised compositions – both pen and ink drawings featuring white forms against a dark ground – and helps to identify the artwork to which Picasso’s tableaux respond. It was a work of great importance to Newman: Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece.20

Fig.9

Matthias Grünewald

Isenheim Altarpiece c.1510–15, view with the panels closed

Musée Unterlinden de Colmar, Colmar

Photo: Musée Unterlinden de Colmar, France/Bridgeman Art Library

In early summer 1964, Newman and his wife Annalee visited Europe for the first time, and took the opportunity to travel to Colmar in France to see Grünewald’s famous altar, completed for the Antonite hospital and monastery in nearby Isenheim in 1515 (fig.9). Newman’s library contains a few books dating from the late 1950s and early 1960s regarding the artist and his school, but his interest in Grünewald probably took shape much earlier.21 In 1966 he explained to an interviewer his attraction to the work:

Grünewald’s Crucifixion is maybe the greatest painting in Europe, but one of the things that intrigues me about the [painting] is the act of active imagination on [Grünewald’s] part. That he was not illustrating so much the Christ in terms of the legend, but since he was doing it for a hospital of syphilitics, that he was able to identify himself with the human agony of those patients, that he was willing to turn the Christ figure into a syphilitic. Now this of course is one of the boldest things that anyone could have done. Yet I think this is part of his genius.22

Grünewald’s work is a polyptych retable that comprises two sets of hinged panels, painted on the front and back, which open in two stages to reveal a polychrome wood sculpture of St Anthony on the interior. In the closed state to which Newman refers, Christ’s suffering on the cross is magnified by his disease-pocked skin and gnarled limbs. The cause of his medical affliction is not syphilis but rather ergotism (known in Grünewald’s time as St Anthony’s Fire), a disease caused by eating rye bread infected with a fungus. Symptoms of the illness included hallucinations, gangrene, muscular spasms and burning sensations of the flesh. As Mark Godfrey’s research on Newman’s Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachtani cycle of 1958–66 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) has revealed, the artist was drawn to the Isenheim Crucifixion because it provided a precedent for ‘using the Christian narrative as a means of addressing contemporary suffering’.23 Newman himself made the connection explicit in interview comments that were excised from a broadcast interview and published by Godfrey, in which he compared the suffering of Jesus to that of victims of contemporary violence: ‘I think the pain’, Newman confessed, ‘was terrible for Jesus, but it somehow – I suppose maybe this is blasphemous – but it seems mild compared to the kind of physical pain people suffer today.’24 He was referring to the atrocities ‘going on in Vietnam, or the sort of things that happened in Hiroshima’, but surely also had the victims of the Holocaust in mind.25

Creation

Thus it is clear that during the Second World War, and into the Vietnam era, Newman registered the magnitude of the eradication of human life that made his reality tragic. Adam and other paintings were his answer. His insight into the depth of the contemporary historical crisis spanned his adult life. Shortly before his death in 1970, he put it this way:

About twenty-five years ago for me painting was dead. Painting was dead in the sense that the situation, the world situation, was such that the whole enterprise as it was being practiced by myself and by my friends and colleagues seemed to be a dead enterprise … What it meant for me was that I had to start from scratch as if painting didn’t exist … The issue for me … was: What are we going to paint? The old stuff was out. It was no longer meaningful. These things were no longer relevant in a moral crisis, which is hard to explain to those who didn’t live through those early years. I suppose I was quite depressed by the whole mess … We couldn’t build on anything. The world was going to pot. It was worse than that. It was worse than that.26

The antithesis of destruction is creation. From that perspective, the significance of Newman’s creation of Adam is that it serves as a model of creation in general. Adam (the painting) could not be made out of nothing, ex nihilo, as the Old Testament asserts humanity was. The canvas and its surface was ‘mud’ (fabric, pigment, binder, medium) that could only be brought to ‘life’ as Adam via the conventions that Newman acknowledged, addressed and transformed to express his ‘real statement’.27

In this In Focus I have attempted to adduce – through the formal criticism of Adam’s pictorial effects – the structure of beholding to which I believe those effects give rise. I have also tried to draw out the necessity of attending closely to Newman’s mode of address in any attempt we make to understand his statement. But in addition, my goal has been to align Adam as a work of art with Newman’s express commitment to the themes of autonomy and relationship that he stressed in his own account of creative activity. Moreover, I have tried to argue for the significance of those themes as they are exposed to us through other dimensions of Newman’s practice, not just in photography, but also in his retrospective testimonies of what he thought the implications of his creative acts were. Taking the appearance of Adam as the phenomenon to be understood requires, one might say, a methodological approach that allows the ‘self-evidence’ of the work to become manifest. Still, the task seems at once self-defeating, for what methodological tactic could ever purport to reveal the metaphysical truth towards which Newman believed his painting pointed? The German philosopher Martin Heidegger captured the basic problem when he described the thought-twisting enterprise demanded by such metaphysical phenomena as letting ‘that which shows itself to be seen from itself in the very way it shows itself from itself’.28

Newman’s art solicits from his beholders a flexible attunement, one that can acknowledge the revelation at the heart of his expression; that recognises his authority as being in a position to reveal something to us; and that is open to the possibility of the work of art being the vehicle of that revealing. At the same time, our bearing towards the meaning of his paintings must be directed by the conventions that are internal to the history of art, and that underwrite our very capacity to recognise the appearance of what is ‘revealed’. (That just is what will render our ‘experience’ of the work of art an interpretation of Newman’s meaning, rather than a mere response to the object before us.) In short, ‘self-evidence’ is just one of the things that a medium’s conventions might permit as an effect of the artist’s expression. Newman’s art compels us to subordinate the empirical explanation of its history – the causal account of the circumstances of its production and reception – to the understanding of his creative proposition, his ‘total reality’.29 Take, for instance, October 1947, when Newman published ‘The First Man was an Artist’, in which he offered his account of Adam’s role in creating a world.30 The syllogism should be obvious. The first man was an artist; Adam was the first man; therefore Adam was the first artist. So: what was his art?

Creating scale: finding a place to be oneself, with others. For Newman, that took the form of giving the viewer a place to be, and thus a place to be with him, in balance. When he came to stage a photograph of himself in front of Cathedra in 1958, casting his shadow on its surface while looking at it with another person, whose shadow was also cast, he was responding to the vital assignment of creating scale.31 In painting, Newman found the means of recreating the totality of human being. The task involved him, and coming to understand the implications of that task involves us, too.