The trajectory of Barnett Newman’s Adam 1951, 1952 (Tate T01091), from its display in a disastrous exhibition to its acquisition by a major institution, mirrors the development of Newman’s reputation in the 1950s and 1960s. However, the painting was not simply swept along by Newman’s acceptance as a major artist – a reputation that was widespread by the time Tate acquired the work in 1968. Rather, through its ownership and exhibition history, Adam was one of the paintings at the centre of the re-evaluation of Newman’s significance in the late 1950s. This essay discusses the early history of the painting’s ownership and the responses engendered by its first exhibitions, examining in particular the way that these responses can be mapped onto the transition from abstract expressionism to colour field painting and minimalism as vanguard styles in the 1960s. It is my contention that the visual qualities of Adam, and the role of the painting’s previous owner, Ben Heller, were of equal relevance to both colour field painting and minimalism, expanding Newman’s audience while at the same time highlighting his ambivalent relationship with the new art of the 1960s.

The painting’s debut

Adam was one of the last two works painted for Newman’s second one-man show held at the Betty Parsons Gallery on East 57th Street, New York, in 1951. The opening of this exhibition brought to an end an extraordinary burst of creativity that had been instigated by Newman’s painting of Onement I in 1948 (Museum of Modern Art, New York) – one that was never repeated again in Newman’s career.1 Newman’s close relationship with Betty Parsons dated back to 1944, when he began writing catalogue texts and arranging exhibitions for her at the gallery of the Wakefield Bookshop on 55th Street, which Parsons then managed.2 After Parsons established her own gallery in 1946, Newman wrote several more catalogue texts for her exhibitions and joined her roster of artists, which included his friends Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko.

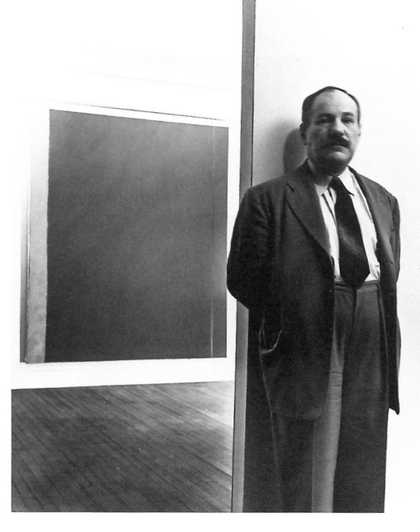

Fig.1

Hans Namuth

Barnett Newman with Adam at his exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, 1951

© Hans Namuth Ltd, New York

Parsons gave Newman his first solo exhibitions in 1950 and 1951, and Adam was included in the latter show alongside other now-celebrated works such as Vir Heroicus Sublimis 1950, 1951 (Museum of Modern Art, New York). An installation shot of Newman and Adam taken at the exhibition shows that at this point the thick red stripe near the painting’s centre was yet to be added (fig.1), and in the list of works for the exhibition (all of which were untitled) the painting was described as ‘brown with scarlet and maroon stripe’.3 Perhaps because Adam was executed shortly before the exhibition opened, Newman was ‘only 90% satisfied with the work’, hence his need to revisit it afterwards.4

Newman had sold only one painting in his first exhibition, but in his second not a single work was sold, including Adam (which was priced at $2,000). Both exhibitions were roundly condemned by critics: Barbara Reise later recalled that the shows ‘met ignorance, hostility and complete incredulity on the part of the New York art establishment’, while Thomas Hess remembered that ‘when Newman’s show opened on April 23, 1951, almost nobody came. What reviews there were were unfavourable’.5 Hess, the editor of Art News, later became one of Newman’s most energetic supporters, but he did not respond favourably to Newman’s work at first, describing him in a review in the magazine as a ‘genial theoretician’ in a ‘race with the avant-garde’.6 Hess was closely associated with New York School painters, above all Willem de Kooning, and was seemingly put off by Newman’s intellectualism, hence the teasing description of the artist as a ‘theoretician’. But aside from the possibility that Newman’s writing and extensive education initially made him suspect within the milieu of abstract expressionism, his rigorous, austere paintings challenged prevailing abstract expressionist aesthetics. This view was aptly characterised by David Sylvester, another critic who subsequently supported Newman’s work:

The rejection of Newman was, of course, the traditional fate of The Ugly Duckling, the character who appears on the scene when a member of a different species is expected. His role in the context of the Abstract Expressionists is similar to [Paul] Cézanne’s in the context of the Impressionists: to create a more rigorous idiom than that of his comrades while remaining involved in their kind of subject-matter.7

Within Newman’s oeuvre as a whole, however, Adam is closer to the work of contemporaries such as de Kooning and Jackson Pollock than most of Newman’s other work, particularly after the addition of the third stripe in 1952. Hess suggested that Adam was a conscious attempt to depict the Kabbalistic concept of tsimtsum, and that ‘the wide orange-red stripe added to the left center is slightly curved, turning to the bottom left as if responding to pressures of contraction and reacting against them. The side bands of color act as contracting forces, metaphors of Tsimtsum’.8 Hess responded to the stripe as if it were convulsive rather than static, and he compared the work with Newman’s earlier Genetic Moment 1947 (Fondation Beyeler, Riehen and Basel), which shares its ‘trunklike’ stripe. Hess also drew a comparison between Adam and Newman’s Achilles 1952 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), with its jagged form atypical in Newman’s work and its ‘central, vivid orange shape cut by black as a continent is cut by the ocean shore’.9 The connections that Hess draws between Genetic Moment, Adam and Achilles suggest a path not taken by Newman, one that diverges from his characteristic straight lines and is more easily reconciled with the work of Newman’s abstract expressionist contemporaries.

Collecting Adam

Adam (in its final state) and Achilles were transitional paintings, completed after the disappointment of Newman’s 1951 exhibition, as the artist entered what Hess called his ‘blackest years’.10 Between 1953 and 1957, during which time Adam remained in his studio, Newman painted little (the Newman catalogue raisonné lists only ten paintings for this period) and exhibited only one painting.11 In her chronology of the artist’s life, curator Melissa Ho has written that during the mid-1950s ‘even with [Newman’s wife] Annalee working two jobs, the Newmans’ financial situation is precarious. The couple resorts to taking loans, pawning a few valuables, and, in Barney’s case, trying to develop a winning scheme at the horse track’.12 Newman’s financial difficulties could easily have led him to abandon painting altogether at this point, but fortunately he met Ben Heller, the young president of William Heller Inc., the textile company. Ben Heller had begun to collect art soon after graduating from Bard College, New York, in 1948. He initially focused on European art, but soon became an important collector of American artists such as Rothko and Pollock.13

Newman met Heller at a party held by the writer R.H. Friedman in 1956, from which he took Heller, Friedman, Pollock and their respective wives to visit his Manhattan studio at 100 Front Street, ‘way downtown, in the coffee district, in a building full of coffee merchants and marvelous odors’, as Heller has described it.14 Heller’s initial response to Newman’s work was that ‘the emperor has no clothes’ (a response reminiscent of Hess’s 1951 review), but he was sufficiently intrigued to visit Newman’s studio a second time, and then a third, ‘by which time I was convinced Barney was a great painter’.15 In 1957, in a turning point in Newman’s career, Heller bought Adam from him for $3,000, along with another work, Queen of the Night I 1951 (National Museum of Art, Osaka).16 When asked in 2016, Heller could not recall why he purchased Adam in particular, writing ‘there were so many wonderful works there [in Newman’s studio] it was hard to choose’.17 However, the characteristics of movement and immediacy that made Adam one of Newman’s most expressive works, and to which Hess responded, may have made the painting stand out for a collector particularly associated with Pollock.18

By this time Newman’s work had been included in group shows at the Walker Art Center and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, both in Minneapolis, while the influential critic Clement Greenberg had declared the artist’s significance in essays for Partisan Review.19 Nonetheless, Newman remained unrecognised by the most important bastion of taste, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, which had excluded him from exhibitions such as Fifteen Americans in 1952 and the touring exhibition Modern Art in the United States (which presented abstract expressionism to many British viewers for the first time when it was shown at the Tate Gallery in London in 1956).20 In 1958 Alfred H. Barr Jr and Dorothy Miller of MoMA were planning a major international touring exhibition, which was originally to have been called Abstract Expressionism and to include leading American abstract artists – but not Newman. It was at this point that Heller interceded on Newman’s behalf, as he later recalled:

Alfred [Barr] came up to discuss what we could lend … we were having a discussion, and I said, ‘Well, where’s Barney Newman?’ And he said, ‘Oh, Barney isn’t an abstract expressionist. The show is to be about abstract expressionism and Barney Newman isn’t an abstract expressionist. He comes out of [Russian abstract painter Kazimir] Malevich.’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t see it that way. But let’s just assume it is, the show is really about leading trump, and Barney Newman is trump … one of our chief trumps. When was the last time you looked at Barney Newman’s work?’ He said, ‘1951’, or whatever, at the show at Betty Parsons’. So, I said, ‘If I hang a show for you and Dorothy Miller, if I hang Barney’s work, will you come down and look at it?’ And he said yes. So, I went down there, I worked with Barney and I arranged a hanging for Dorothy and Alfred.21

The result of this visit – a ‘show’ hung by Heller – was that Barr and Miller included Adam and three other works by Newman in the exhibition, changing its title to The New American Painting to reflect Newman’s inclusion (and perhaps Barr’s continued belief that Newman was not an abstract expressionist). Heller lent six paintings to the exhibition, including works by Rothko, Still, Adolf Gottlieb, Bradley Walker Tomlin and Jack Tworkov, and undoubtedly it was Heller’s status as a collector and lender to the show that enabled him to make Barr reconsider his opinion of Newman.22

Fig.2

Opening of The New American Painting at Kunsthalle Basel, 1958, with Adam partly visible in the upper left corner

Photo: Ateliere Moeschlin and Baur/Kunsthalle Basel

Fig.3

Installation view of The New American Painting at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1959

Photographic Archive, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, IN645.14

Photo: Soichi Sunami

The first major international exhibition of abstract expressionism, The New American Painting travelled to institutions in eight European cities (Basel, Milan, Madrid, Berlin, Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris and London) in 1958 and 1959, before concluding its tour at MoMA (for installation views at Basel and MoMA, see figs.2–3). The three other works by Newman in the exhibition, aside from Adam, were Concord (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Abraham (Museum of Modern Art, New York) and Horizon Light (Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, Nebraska). They were all painted in 1949 and had been exhibited in Newman’s first show with Parsons in 1950, and all were loaned by the artist. The inclusion of only earlier works was typical of Newman’s exhibitions in the late 1950s, such as his major shows at Bennington College in Vermont (1958) and French and Company in New York (1959), which both consisted only of paintings from the 1940s and early 1950s. One reason for this was simply that Newman had produced so few paintings since 1952. There may have been another reason, however: it seems likely that Newman did not exhibit any of his mid-1950s paintings until the 1960s because he first wanted to secure approval for those earlier works that had met with indifference, or worse, when initially exhibited with Parsons. After all, Newman took the extraordinary step of buying back Untitled 1, 1950 1950 (private collection) from Alfonso Ossorio in 1953 because, in his words, ‘the conditions do not yet exist … that can make possible a direct, innocent attitude towards an isolated piece of my work’.23 For an artist in Newman’s position this was a remarkable act, but one that testified to his meticulous approach to presenting his work. He may also have remembered how he first exhibited Adam when he was ‘only 90% satisfied with the work’, and possibly sought to avoid repeating the resulting situation of having to continue work on a painting after its initial display.

Newman’s growing reputation

Participating in The New American Painting seems to have made an immediate difference to Newman’s reputation and the desirability of his work, as by the end of the exhibition tour Newman had sold all three of the paintings he had loaned to the exhibition. Two went to friends of Newman: the artists Thomas Sills and Jeanne Reynal bought Horizon Light, while Parsons purchased Concord (which she sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1968). As acquaintances of the artist, Sills, Reynal and Parsons would have known about these works for a long time, but the cachet of their having appeared in a prestigious touring exhibition no doubt made purchasing them more desirable.

Most significantly, however, MoMA acquired Abraham from the artist in 1959 using funds provided by the architect and collector Philip Johnson. The painting thereby became the first work by Newman to enter a US institution, putting the seal on the museum’s acceptance of the artist. This acquisition was again facilitated by Heller, and originated in Barr’s visit to Newman’s studio in 1958. Heller had intended to purchase Abraham for himself but stepped aside when Barr showed an interest in it: ‘Alfred went like a bird dog to Abraham. He turned to me and immediately asked, “Do you think Barney would sell that?” “Well, that’s supposed to be my next painting,” I said, “but I’ll ask Barney.” And now Abraham hangs in MoMA.’24 Heller, who held positions on committees at museums including MoMA and the Jewish Museum, was keen to see Newman’s work placed in major institutions. He was instrumental in the other acquisition of a Newman painting by a public institution at this time: Day Before One 1951, which was acquired by the Kunsthalle Basel in 1958.25 This impulse presumably motivated his decision to offer Adam for purchase by the Tate Gallery in 1968, and his gift of Vir Heroicus Sublimis to MoMA in 1969.

The New American Painting introduced many viewers around the world to abstract expressionism. Yet its tour took place at a time when a new generation of artists, such as Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella, were reacting against gestural abstraction and the discourse which accompanied it, epitomised by Harold Rosenberg’s 1952 essay ‘The American Action Painters’ that viewed painting as an existential drama.26 The most enthusiastic commentator on the exhibition in England was Lawrence Alloway, a curator and critic with a passion for American culture who was already familiar with Newman’s work. Alloway first visited the US in 1958, and he went to Newman’s studio and was driven by Betty Parsons to see the artist’s Bennington College exhibition.27 Reviewing the show, Alloway picked up on Newman’s relevance to hard-edge and colour field painting when he wrote that ‘Newman’s presence in The New American Painting is a surprise to everybody (including some of the staff of the Museum of Modern Art, probably) but he is at the top of the show. His economical means and dead-pan technique makes everybody else’s work risk fussiness and elaboration.’28

Newman’s influence on British artists was manifest in exhibitions such as Situation (RBA Galleries, London, 1960), which showcased a new generation of British abstract painters. Art historian Alan Bowness, writing in 1967, recalled that after The New American Painting Newman ‘immediately became a hero-figure for the younger generation of British artists’,29 and that the painting in Situation ‘was in part a sign of the ascendency of Rothko and particularly Newman over Pollock and [Franz] Kline and De Kooning’.30 John Hoyland, one of the artists included in Situation, has acknowledged the influence of Newman, while there are also clear echoes of the artist’s work in the painting of Robin Denny and William Turnbull.31 Another Briton impressed by Newman’s paintings in The New American Painting was the collector Ted Power. Already an established collector of contemporary American painting, Power bought his first Newman, By Twos 1949 (private collection), after seeing the exhibition, followed soon after by Eve 1950 (Tate T03081), White Fire I 1954 (private collection) and White Fire III 1964 (private collection).32 Power’s son Alan, meanwhile, purchased Newman’s 1955 painting Uriel (Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg) in 1964, and persuaded Newman to come to London and supervise the installation of the painting in his home. A party in Newman’s honour was arranged to coincide with the visit, which was attended by artists including Turnbull and artist Allen Jones, and so reinforced the artist’s ties with England.33

At the same time that he enjoyed the company of younger artists, Newman remained anxious to avoid any misunderstanding of his intentions. His statement for the catalogue of The New American Painting denounced the ‘death image’ of geometry, singling out Malevich and Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, two pioneers of abstract art, in the process: ‘in a world of geometry, geometry itself has become our moral crisis. And it will not be resolved by jazzed-up kicks but only by the answer of no geometry of any kind. Unless we face up to it and discover a new image based on new principles, there is no hope for freedom.’34 Barr had thought that Newman ‘came out of Malevich’, and it was perhaps to correct this view that Newman made clear in the catalogue of The New American Painting that geometry was a ‘trap’ of generic art, whereas he was working to ‘discover a new image based on new principles’.35 Reviewing the Paris iteration of the show, however, Pierre Restany nonetheless characterised Newman as ‘geometrical’, on the basis of paintings including Adam.36 In fact, if there was a case to be made for Newman as a geometric painter, then Adam might be one of the canvases in which this tendency was most evident. Michael Fried, a critic closely associated with Stella, wrote in 1962 that Adam was an example of how Newman sometimes tried to distance himself from Mondrian and geometrical abstraction ‘by presenting elements in a relation that has deliberately been made awkward or askew’, but noted that ironically ‘he is probably never nearer to geometric thinking than when he does this’.37 In this way Adam, and particularly its central stripe, can sustain contrary readings: it is expressive and in keeping with the visceral impact of abstract expressionism, while also displaying the compositional concerns (‘deliberately … awkward or askew’) characteristic of artists such as Stella.38 One interpretation follows Newman in his belief in ‘a new image based on new principles’ while the other foregrounds the artist’s problematic relationship with earlier abstraction.

The Heller collection: At home and on tour

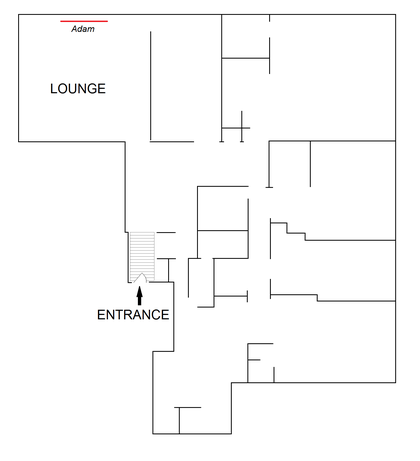

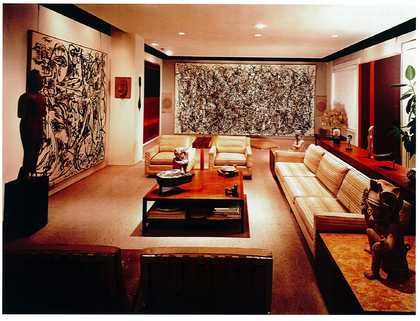

After The New American Painting, Adam returned to the Heller residence, a tenth-floor apartment at 151 Central Park West in New York, which had been refurbished by architects Allen and Edwin Kramer to allow Heller to display his large abstract expressionist artworks.39 Adam hung in the Hellers’ lounge alongside three Pollocks (One: Number 31, 1950 1950 and Echo: Number 25 1951, both Museum of Modern Art, New York; and Blue Poles: Number 11, 1952 1952, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra), opposite Rothko’s Four Darks in Red 1958 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York), painted in a similar earthy palette. Visitors to the apartment would have seen Adam from the entrance hall before entering the lounge and turning to face one of the large Pollocks – One to the left, for instance, or Blue Poles to the right (see figs.4–5).40 Adam therefore served as one of the starting points of visits to view Heller’s collection.41

Fig.4

Floorplan of the Hellers’ New York apartment, showing the entrance hall and lounge, and the position of Adam on the lounge wall

Fig.5

Photograph of the Hellers’ lounge taken in 1960, showing (from left to right) Pollock, Echo: Number 25 1951; Rothko, Four Darks in Red 1958; Pollock, One: Number 31, 1950 1950; and Newman’s Adam

Barnett Newman Foundation, New York

The Hellers’ apartment was well known, both for its architectural interest and for its owners’ collection. Newman’s wife Annalee remembered that ‘everyone wanted to see Ben Heller’s apartment, it was so beautiful’, while Rothko called it ‘the Frick of the Upper West Side’, referring to the private collection of industrialist Henry Clay Frick that is housed in his former home in Manhattan.42 Barr, meanwhile, wrote that ‘when a visitor, American or foreign, or even a New Yorker, asks where he can see the best accessible collection of American action paintings in New York, one’s first thought is the Hellers’ apartment’.43 (In 2005 Heller recalled that by 1958 MoMA ‘was sending everybody to my place, because we had more than the museum had … We got about 5,000–6,000 visitors a year. Most of the European museum directors learned about American painting in our place’.)44 Heller believed that it was part of his responsibility, as the owner of an important collection, to provide a degree of public access to it, and regularly allowed groups and societies to visit his apartment: notices in the New York Times show that groups visiting the collection included the 7th Annual American Federation of Arts tour (14 November 1959); the Radcliffe Club tour (12 December 1959); the Spence School (18 April 1961); and the Junior Division of the New York League of the Association for the Help of Retarded Children (26 October 1965).45

Fig.6

Installation view of The Collection of Mr and Mrs Ben Heller, Baltimore Museum of Art, 1961

Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore

Fig.7

Installation view of The Collection of Mr and Mrs Ben Heller, Art Institute of Chicago, 1961, with Vir Heroicus Sublimis visible on the right

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

Fig.8

Installation view of The Collection of Mr and Mrs Ben Heller, Cleveland Museum of Art, 1962, showing Adam at the left

Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Cleveland, 33289C

It was this sense of obligation to the public that led to The Collection of Mr and Mrs Ben Heller, another major touring exhibition organised by MoMA in 1961–2, which included Adam alongside three other works by Newman.46 This exhibition did not encompass the full range of the Hellers’ collecting; instead, it represented a conscious attempt make an exhibition similar to The New American Painting for a domestic audience.47 As Heller stated: ‘the idea was, my God, why shouldn’t the United States get what Europe got: a chance to see a lot of major paintings?’48 The exhibition was shown in seven American cities (Chicago, Baltimore, Cincinnati, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Cleveland and Portland) – it was not shown in New York, but this was unsurprising considering the comparative ease with which the work of Newman and his contemporaries could be seen there.49 The accompanying catalogue included images of Heller’s apartment, alongside texts by William Seitz, Barr and Heller himself (one of many he has written about artists whose work he collected).50 Having grown accustomed to seeing Adam and his other paintings hung in a particular way in his bespoke Manhattan apartment, Heller recalled that ‘it was perfectly fascinating to see the different contexts [in which the collection was exhibited]: in Chicago the very large Miesian space installed by Jim Speyer; the rather intimate gemütlich rooms at Baltimore’.51 This contrast between the installations in Chicago and Baltimore can fortunately be seen from installation shots, while the Cleveland iteration (which, like Baltimore, included an abundance of potted plants) was particularly well documented (figs.6–8).

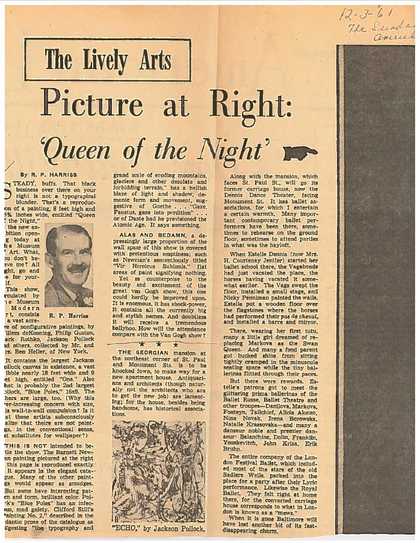

Fig.9

R.P. Harriss, review of The Collection of Mr and Mrs Ben Heller in the Baltimore Sunday American, 3 December 1961, with a reproduction of Newman’s Queen of the Night I

Library and Archives, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore

The presence of Newman’s work in the exhibition continued to perplex commentators, such as R.P. Harriss writing in the Baltimore Sunday American. Newman’s long, vertical painting Queen of the Night I was reproduced alongside the review by Harriss, who pointed out to his readers that ‘that black business over there on your right is not a typographical blunder. That’s a reproduction of a painting … What, you don’t believe me? All right, go and see for yourself’ (fig.9).52 Harriss might have been making a reasonable point about the appearance of Newman’s work in reproduction, were it not for the fact that he made clear his low opinion of the artist’s work. Later in his review, the critic wrote: ‘a depressingly large proportion of the wall space of this show is covered with pretentious emptiness: such as Newman’s sententiously titled “Vir Heroicus Sublimis”, flat areas of paint signifying nothing’.53 Adam was not mentioned by name, however: as these quotations indicate, Newman’s most extreme paintings in terms of dimensions (the narrow Queen of the Night I and the 5.5 m wide Vir Heroicus Sublimis) attracted particular attention. Adam thereby escaped singling out from hostile critics, although it was tarnished by the accusations against Newman as a pretentious bore that were lodged by journalists such as Harriss, who preferred the ‘infectious, mad gaiety’ of Pollock’s Blue Poles and the ‘hellish blaze of light and shadow’ of Still’s 1949 No.2 1949 (private collection).54

It cannot have helped that Newman’s work was again shown alongside Rothko’s, as it had been in both The New American Painting and in Heller’s home, inviting comparisons between the two artists (see figs.2 and 5). Henry J. Seldis, writing in the Los Angeles Times, bracketed the two artists together, writing that they both ‘deal with emptiness to some extent’. However, whereas he found that Rothko’s paintings ‘evoke a sort of mystery that is ever changing but predictably nourishing’, in contrast he felt that ‘the void that Newman puts before us neither terrifies nor exhilarates but simply bores me’.55 Newman’s reputation had grown substantially since his inclusion in The New American Painting, but even so it still lagged behind that of Rothko. (By this time, Rothko had had a retrospective at MoMA which was in the process of touring internationally, and a one-man exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1954, while Newman did not receive a solo museum exhibition until 1966.) When the Heller collection exhibition was publicised in an article in the Chicago Tribune, for instance, Newman was not one of the eight exhibiting artists whose names were mentioned.56 This difference in the artists’ reputations was surely due in part to their respective galleries: Rothko, like Newman, was represented by Parsons early in his career, but left her to join Sidney Janis in the early 1950s before moving to Marlborough in the 1960s, which was particularly active in promoting his work around the world. Newman, on the other hand, had no exclusive relationships with galleries after leaving Parsons in 1951, and so had no equivalent force driving interest in his work.

This made Heller’s continuing advocacy all the more important. In writings such as his catalogue texts for the exhibitions Black and White and Toward a New Abstraction, both held at the Jewish Museum in 1963, he emphasised continuities between Newman and the following generation without claiming that Newman was making geometric paintings himself, as Restany and Fried had suggested. In his essay for Toward a New Abstraction, which included Kelly, Stella and Kenneth Noland, Heller wrote that: ‘Devoted to a “purer”, hieratic conception of the act and meaning of painting, these artists seem to stem most particularly from the revolutionary development of Pollock, Newman, Rothko and Still’.57 Within this quartet, however, it was Newman whom Heller identified as particularly relevant to the artists in the exhibition:

In order to attain this rather classical orientation, which I take in part to be a reaction against the idea of an excessive emphasis on self in some abstract expressionist painting and criticism, the artists seem to have undergone a process of reduction towards an almost irreducible minimum statement. In this sense, particularly, Barnett Newman was an important influence (probably the most important single influence on these and other painters during the past several years), for, as he has shown, reduced terms do not mean reduced results, lowered aims, simple paintings. An extraordinary range of expression and emotion is achieved by these ‘new abstractionists’. They are lyric and expansive, they are controlled and grave.58

Throughout the early 1960s Newman was repeatedly cast in the role of a precursor. Donald Judd, whose literalism might seem diametrically opposed to Newman’s spirituality, nonetheless wrote in 1964 that ‘it’s not so rash to say that Newman is the best painter in this country’.59 The relationship was a complex one, however, as art historian Richard Shiff has described in an important essay.60 Newman declined invitations to participate in exhibitions with names such as The Formalists and Geometric Abstraction, which sought to make an explicit connection between Newman and younger geometric artists. He did agree to take part in the US contribution to the 1965 São Paulo Bienal, organised by Walter Hopps, in which he was the figurehead of an exhibition that also included Judd, Stella, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin and Larry Poons, but when Hopps attempted to present Newman as a representative of the ‘new American formal painting’, Newman requested that the statement be removed.61 Newman clearly enjoyed seeing his work appreciated, but he was careful to retain a measure of control in how it was presented.

After the Heller collection tour Adam was not exhibited again until it entered the Tate collection in 1968. It did so despite the reservations of Sylvester and Power, both of whom were trustees of Tate at the time and felt Heller’s asking price of $35,000 (then £14,583) to be excessive.62 Eventually, however, the trustees agreed that Adam was ‘especially desirable’, and with the help of a $5,000 contribution from S. Herbert Meller through the American Federation of Arts, Adam was purchased at Heller’s asking price.63 In 1980 it was joined by Eve, acquired from Ted Power. Newman’s wife Annalee wrote at the time: ‘I think he [Newman] thought of them as a pair because he worked on the first painting and then on the second continuously until they were finished and then named them “Adam” and “Eve”’.64 Unsurprisingly the two works have regularly been displayed together, such as in the 2016 Abstract Expressionism exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the organisers of which explicitly linked the exhibition back to The New American Painting. The works, previously owned by two of Newman’s most important patrons, present a striking contrast: in Eve it is only the subtle stripe along the right edge that disrupts the field of unmodulated red paint, while Adam, with its maverick stripe veering from the vertical, is convulsive and unsettled, showing much more of an impulsive streak. Exhibiting the two works together demonstrates why Newman went from being the ‘ugly duckling’ of abstract expressionism to a central figure for two generations of artists.