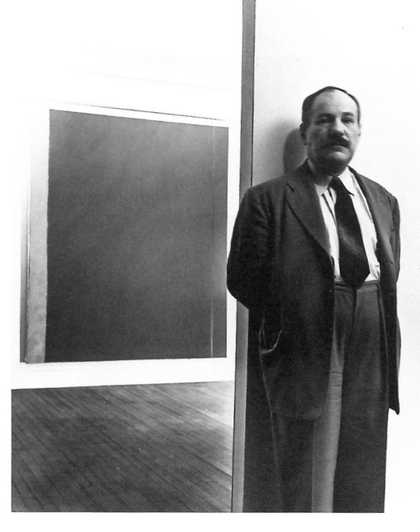

Fig.1

Hans Namuth

Barnett Newman with Adam at his exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, 1951

© Hans Namuth Ltd, New York

During his second one-man show at Betty Parsons Gallery in New York in April 1951, abstract expressionist painter Barnett Newman (1905–1970) exhibited a large, untitled oil painting, now known as Adam (Tate T01091; fig.1). At two and a half metres high by two metres wide, the canvas then comprised just three elements: a large expanse of deep, reddish brown and two bright red bands running from the top to the bottom of the canvas.3 The visual reach of the amplified field was constrained laterally on both sides: on the left, by the broad plank of cadmium red that firmly declared the painting’s framing edge; and less emphatically on the right by a much narrower, two-centimetre strip of the same colour running parallel to the right edge, at a distance of fifteen centimetres.

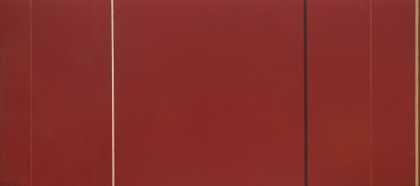

In 1952 Newman changed the painting, and its internal balance, by adding an assertive third band between the two original verticals (fig.2). This explains the artist’s inscription at the work’s lower left corner, which gives two distinct years of completion: ‘Barnett Newman 1951 + 52’ (the ‘plus’ sign was an important indicator that he considered it finished at each date). Wider at its base than at its top, and angled just below its midpoint as if the lower half were hinged or jointed, the inserted red strut responds to what is now felt to be a palpable compression of the darker field. It is as if some great physical force is being exerted on the quadrangle by its upper and lower limits, causing the central red wedge to buckle slightly – a force that is then offset or equalised by the newly established strength of the painting’s shape and by its bent but unyielding internal structure.4

Fig.2

Barnett Newman

Adam 1951, 1952

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 2429 x 2029 mm

Tate T01091

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2018

This In Focus proceeds in five parts. In the present essay I examine Newman’s decision to add the third band in light of the structure of beholding that it allowed him to establish for the painting’s viewers. At the same time, I attend to how some of the artist’s statements on meaning can be brought to bear on the interpretation of Adam’s pictorial effects. The second essay considers the symbolic relationship of Adam (the painting) to both Adam (the biblical first man) and to Newman’s own creative act as a painter. This assessment is followed by an investigation of certain photographs of Newman posing in front of his works, in which I contend that the staged character of the portraits – or better, their formal structure of implication – helps us understand more precisely Newman’s commitment to the persistence of human ‘figuration’ within a manifestly ‘abstract’ technical practice. In the fourth essay, art historian Michael Leja discusses the significance of ‘beginnings’ for Newman and his abstract expressionist peers, while analysing the cultural and philosophical stakes of their interest in origins and originality. Finally, art historian James Finch maps the exhibition and collection history of Adam, demonstrating the key role the painting played in the public’s appraisal of Newman’s art in the late 1950s.

Totality

To adopt one of Newman’s preferred terms, the standing girder that the artist incorporated into Adam in 1952 helps establish the scale of the presently concentrated field. The word not only suggests the band’s role, as a channel or streak of light, in balancing the visual weight of what before was a broad, dark plane. It also evokes its bracing capacity to institute a specific pictorial quality that Newman insisted was independent of any canvas’s mere size (large though this one happens to be).5

Newman often voiced his desire to establish for viewers of his paintings a tangible sensation of scale, a ‘sense of place, a sense of being there’.6 He considered the challenge of creating scale to be ‘the real problem of painting’.7 ‘Size doesn’t count’, he explained. ‘It’s scale that counts. It’s human scale that counts, and the only way you can achieve human scale is by content.’8 For Newman, space, scale and content were bound to each other. Together, they constituted the ‘totality’ of painting that he strove to create.9 Totality was something more than just formal coherence, more than a unity of design that his deceptively simple compositions often seem at first glance to embody. Totality was metaphysical. It could not be produced simply by conforming to commonly held aesthetic ‘rules’ or adhering to artificial canons of beauty. (This does not imply, however, that Newman considered totality to be a quality existing outside the artistic conventions by which it could be made the content of painting.) Nor was it infallibly given, as if perceiving it were a matter of reacting to an automatic trigger. Instead, it had to be achieved: totality involved the successful expression of intent, within the medium of painting, that a viewer might come to understand and acknowledge. It comes as no surprise that Newman believed strongly in the ethical dimension of the relationship between painter and beholder, and developed forms of pictorial address that would, he hoped, foster it.10

Fig.3

Barnett Newman

Eve 1950

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 2388 x 1721 x 50 mm

Tate T03081

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2018

At some point after the 1952 revision to his canvas, but before its 1957 sale to collector Ben Heller, Newman gave his painting its title, Adam.11 It is possible that he titled Eve 1950 (Tate T03081; fig.3), which was also exhibited untitled at the 1951 Parsons show, at the same time, establishing them as a pair.12 In my initial observation that Adam, in its first state, contained ‘just three elements’ (a field and two vertical bands), and that in its second includes the ‘added’ third stripe, I have introduced a difficulty typical of describing Newman’s works. When we say that Adam is a painting with a deep brown field and three vivid red-orange bands or ‘zips’, we implicitly take those latter elements as figures on top of or against a continuous ground, rather than seeing the ‘ground’ positively, as three broad channels of shaded colour, almost sepia in hue, between more vibrant bands.13 But if we were to see the ground in that unusual way, we might describe Adam as comprising six vertical sections of disparate widths that alternate between just two colours, red and brown – or even two values of a single colour, since cadmium red pigments, when shaded with the addition of black, yield a deep mineral colour like that of an earth pigment such as burnt sienna.14 (That Newman meant to evoke the association in Adam between its colour and soil or clay is suggested retrospectively by his 1965 comment on the hue of the earthen ground in Brazil: ‘The first man was called Adam. “Adam” means earth but it also means “red”.’)15 Formal description parses the visual totality of the image into constituent parts, when what Newman valued most was ‘wholeness’. In an interview with the art critic David Sylvester, Newman said his paintings ‘physically declare the area as a whole from the very beginning … the wholeness has no parts’.16

Did Newman think he had failed to achieve totality or wholeness in the first iteration of what would become his re-created painting? He testified, again in retrospect, to having been ‘only 90% satisfied’ with the untitled canvas he exhibited in 1951. Yet instead of destroying it (his usual tactic for dealing with failed works), he ‘found [he] could finish’ it.17 He explained in a 1963 interview:

Well, why did I change it[?] I had it in a show; it always sort of bothered me. I thought it had fantastic quality, but it bothered me … And I then took it home and one night … it came to me that why it was weaker, so to speak, in terms of my feelings … And so I went and took some paint and I made a, introduced a something into the painting which I feel has made it into a real statement, the real statement I wanted to make. Well, it’s possible to say there was an afterthought. I didn’t think it was an afterthought … I’ve done that with two paintings only in my life.18

Fig.4

Barnett Newman

Vir Heroicus Sublimis 1950, 1951

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 2422 x 5417 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2018 Barnet Newman Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Elsewhere in this In Focus it will be important to remember that the other painting to which Newman refers is Vir Heroicus Sublimis 1950, 1951 (fig.4) – but for now, his statement might lead us to wonder, what was the ‘something’ that was missing?19 Working backwards from the solution – the addition of the third band, and the painting’s eventual name – the answer could be simple: what must have been missing was Adam (or, taking him as a representative, ‘human scale’ in general). Given Newman’s commitment to abstraction, it would be unreasonable to expect Adam to depict the biblical first man.20 But it must have been the case that, with its erect column, Newman (eventually) found his painting to harbour something like an expression of Adam’s existence, or being, or agency. Said somewhat differently, Adam’s content involves the implications of Adam having been created and as having been the first man. For Newman, such an understanding would have resulted not simply from an exegetical project (a matter of his interpreting from the book of Genesis what God had done or meant to do in creating Adam and Eve), but rather from a self-reflective one (a matter of Newman trying to understand from his own painting what he had done or meant to do in making Adam). It would not have been lost on the habitual wordsmith that his double reflection on Adam as the ‘first man’, and on himself as the ‘New-man’, could be at once broadly metaphysical and specifically pictorial.

Address

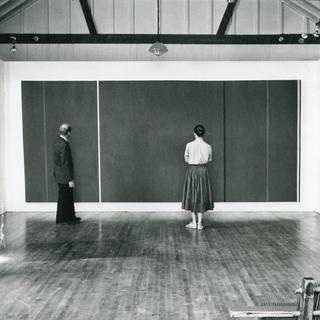

Fig.5

Matthias Tarnay

E.C. Goossen and an unidentified woman standing in front of Vir Heroicus Sublimis at Newman’s first retrospective, Bennington College, Vermont, 1958

Barnett Newman Foundation, New York

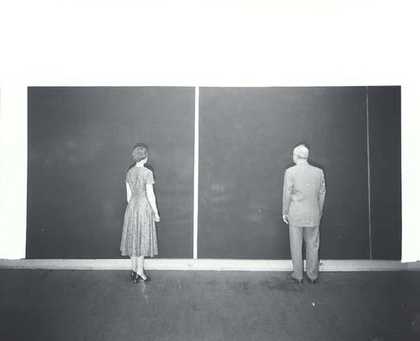

The paintings in the 1951 Parsons show – including the expansive Vir Heroicus Sublimis, the very narrow The Wild 1950 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), and Adam and Eve, all still untitled at this point – came with a specific set of instructions to viewers. The artist affixed a note to the entrance that read: ‘There is a tendency to look at large pictures from a distance. The large pictures in this exhibition are intended to be seen from a short distance.’21 Although it is unclear how close Newman considered the standpoint of that short distance to be, consider a pair of photographs from 1958 that might help us estimate it. The first shows the art critic E.C. Goossen and an unidentified woman posing in front of the 2.4 by 5.4 metre canvas Vir Heroicus Sublimis at Newman’s retrospective exhibition at Bennington College in Vermont (fig.5). The woman stands close and looks straight ahead, while Goossen poses even closer to the painting – my estimate is around one metre away – and looks at the surface obliquely. Newman responded so positively to what this photograph suggested about the intimacy between viewers and his paintings that he soon replicated it in a portrait taken by Peter A. Juley. The image shows Newman and an unidentified woman staged in front of Cathedra 1951 (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam) (fig.6). Both look at the surface obliquely, yet this time stand no more than one foot away.22

Fig.6

Peter A. Juley

Barnett Newman and an unidentified woman standing in front of Cathedra in Newman’s Front Street studio, New York, 1958

Peter A. Juley and Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., J0112534

I will say more about the shared proximity of Newman and his companion to the painting’s surface – and specifically about the shadows their bodies cast upon the plane – in another part of this In Focus.23 First, though, I want to point out that Newman’s ‘short distance’ is an insufficient standard: inexact, it is nonetheless too specific to cover the variable distances that his individual paintings indeed seem to require. The ideal distance from which to view each painting is guided and controlled, I would suggest, by each work’s particular pictorial effects. Those standpoints are determined by Newman, who formally and technically projects them.24 Describing the general effect of his works, commentators often remark on the impression that the imagistic plane, especially in its striking quality of seeming to face the viewer all at once, situates them at a distance (alternatively, they claim to feel absorbed by the colour’s radiance).25 In the case of Adam, that distance is about four to five feet away; for Eve, it is about eight to nine feet. That is the approximate distance from which relatively small variations in surface manufacture are still grasped in their particularity – such as the feathering of paint along the right edge of Adam’s leftmost band; the bleeding and spattering of paint along the central band’s left side, like miniature solar flares; and the uneven density of application that causes the thinnest zip to waver in and out of perception. At the same time, this distance allows the abundant visual force of the whole surface area, and the impenetrability of its flattened space, to seal the belonging of its constituent ‘elements’ into the totality of the virtual plane.

Recall Newman’s canvas in its first state, without the central band (see fig.1). It is reasonable to suppose that in its original condition, the pictorial dimension of the image – a ‘space’ that was not volumetric or atmospheric in any conventional way – must have been qualitatively different than it subsequently came to appear.26 Initially, the spread of vision laterally over the deeply shaded colour – so loaded with pigment that its visual impression conveys a sense of palpable, earthly substance – would have been unimpeded in three directions, or nearly so. On the left the viewer’s ranging gaze would have been hedged by the vibrant red fifteen-centimetre-wide band. It displays markedly disparate qualities along its length: one side exhibits a sharply delimited edge where the colour abruptly stops as the fabric of the canvas support turns the corner of the tacking margin; along its other, a halation of red spreads slightly into the adjacent field, crossing over a still visible linear ridge produced by the masking tape that Newman used to demarcate the limit of the band. The directional brushing along this edge seems to have been imprecisely perpendicular, judging by the slight angles of the wavering strokes to the plumb line.27 But no similarly emphatic barricade would have moderated the eye’s sweep across and over the monochromatic remainder of the array – unless one thinks of the thin, flickering band stretched parallel to the right edge as a tenuous brace. The potential of that thin zip to have served as an internal framing device, though, would have been undermined not only by its fluttering hold over the field’s expanse, but also by a disparity in the painting’s internal scale. The unmediated juxtaposition of the two original verticals causes the leftmost band to read as ‘near’, while the apparent diminution of the thin band begins to look as if it were the result, not of its actual size, but of its distance in ‘far’ space. That attenuation might also suggest a viewpoint from which the field and its constituents are seen at an oblique angle from somewhere off to the left. As a result of their contrast, the unmodulated field in between the bands would have begun to assume the character of a residual spatial volume, with the painting thus acting almost as a container within which its elements stage their drama of proximity and distance. Without its central band, in other words, the picture verged on reproducing, in its play of near and far, a kind of vestigial naturalism.28

As we can now see, things changed in 1952. With the addition of Adam’s third band, Newman moderated the apparent ubiquity of the deep brown field by creating an internal structure with an almost skeletal power to hold the plane together as an imagistic totality. The sweep of vision, previously unconstrained, is now checked in the vertical dimension by the sense of compression that, as I claimed above, the angled strut has a role in producing through its slight buckling. And although Newman would have given little weight to observations regarding merely compositional concerns, it is nonetheless noticeable that the right half of the field has become more balanced with the left, thereby reducing the impression that the thin band diminishes in size due to spatial recession. In particular, note that the broadest curtain of shaded colour – between the thin zip and the ‘new’ central beam – is about twice the width of the one on the pole’s other side. When factoring in the visual weight each band contributes to its local area, the newly stable proportions have the effect of compositionally balancing the left and right halves of the picture. An additional consequence of this intuitively sensed symmetry is that the fifteen-centimetre-wide belt of brown between the thin zip and its closest edge is now transformed into a kind of brace in its own right – one that not only mirrors, in inverse value, the actual size and virtual scale of the brighter band on the left side of the canvas, but that also recapitulates the pictorial role the marginal red zip had played in securing the roving gaze from exceeding the painting’s limit.

Standing

It is my contention that when beholding Adam, Newman meant the viewer to feel as if his or her sight is held by an intense quality of being faced by the painting, and furthermore intended viewers to experience the pictorial effect of being addressed, at once, by the totality of the image.29 Certain features of the central band reinforce the impression that the standpoint projected by the painting pins us to the ground before it. Nearly inscribed into the field (observe the emphatic ridges between colour areas that run the length of each side of the band), its widened base plants the girder at the painting’s lower edge. Vertically erect, yet off-centre and jointed at its midpoint, the viewer can sense the strut’s almost literally physical effort to counterbalance its skewed standing. That anthropomorphic dynamism is strengthened by the band’s proportions and orientation: at twenty centimetres across at eye level, it is roughly the breadth of a human head or skull from the side. Consequently, its form seems to mirror, and thus address, the body of the projected viewer, or to stand for erect posture in a general sense.30 Now recall what Newman said during his interview with Sylvester, quoted above: he considered his paintings to ‘physically declare the area as a whole from the very beginning’. In them, he continued, ‘the wholeness has no parts’. A wholeness that has no parts: one would be hard pressed to find a better description of the phenomenological totality of the human body as it is experienced by living subjects.31 It is a pictorial effect Newman prized. He closed his remarks to Sylvester by saying: ‘One of the nicest things anybody ever said about my work is when you yourself said that standing in front of my paintings you had a sense of your own scale.’32

We are now in a position to see that scale is not a property of objects, but a subjective achievement – and, crucially, one that emerges through relationship. In fact, it would be better to think of scale as an intersubjective achievement rather than a self-generated one. According to Newman, it comes from a sense of one’s standing, apart from the painting, yet in equilibrium with it: think of a set of vintage hanging scales, the instrument that balances one weight in relation to another. To rephrase the description of Adam’s scale: the re-created painting seals itself against the viewer’s imaginative passage into depth; it defeats his or her tendency to drift into its expanding field of colour as if it were an atmosphere permeating a volumetric space, and to ‘lose’ him- or herself in it.33 Rather, it positions the viewer, and in doing so establishes the conditions under which Newman’s structure of beholding asserts the primacy of relationship.

Scale also requires the mutual acknowledgment of those involved in a relationship; or, in the case of painting, with the virtual effect that the canvas hanging on the wall is not merely a ‘thing’, but rather a medium through which the artist expresses himself. As Newman explained to film director Emile de Antonio:

I was constantly concerned in doing a painting that would move in its totality as you see it. You look at it and you see it … The beginning and the end are there at once. Otherwise, a painter is a kind of choreographer of space, and he creates a kind of dance of elements, and it becomes a narrative art instead of a visual art.34

Fig.7

Barnett Newman

Chartres 1969

Acrylic on canvas

3048 x 2896 mm

Daros Collection, Switzerland

© 2018 Barnet Newman Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Bruce White

Attend closely to Newman’s phrasing: the special mode of perception demanded by a properly ‘visual art’ must comprise the dual aspects of ‘looking’ at something and ‘seeing’ it – or more pointedly, must elevate mere looking (taking the canvas as an object that stimulates your eyes) to the level of seeing (understanding the painting’s content through an act of intuition or intellect).35 The significance of this difference can be gleaned from a statement he made in 1969 concerning his triangular ‘shaped works’ Jericho 1968–9 (Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris) and Chartres 1969 (fig.7). Discussing the meaning of those later works, Newman’s thought jumped to the narrow works he had made nearly twenty years earlier, at the same time as Adam and Eve, such as Untitled 1, 1950 1950 (private collection), Untitled 2, 1950 1950 (Menil Collection, Houston) and The Wild. The issue confronting an artist who chose to work with an oddly shaped format, he explained, was to ‘transform the shape into a new kind of totality’. Could the painting, he asked, ‘overcome the format and at the same time assert it? Could it become a work of art and not a thing?’36

Involvement

Newman’s paintings test our sense of the transformed relationship between the actual materials of art (the paint and canvas that constitute each object’s thingly character) and the pictorial effects or virtual world that the work of art, as a vehicle of the artist’s expressive intent, creates or projects. As we have observed, ‘seeing’ a painting – understanding the ‘real statement’ the artist creates through it – is for Newman identical to grasping its ‘human scale’, in pointed contrast to its mere or actual size, no matter how big or small the thing is. Consequently, it should not surprise us that immediately after mentioning a work that would ‘move in its totality’, Newman draws this analogy:

When you see a person for the first time, you have an immediate impact. You don’t really have to start looking at details. It’s a total reaction in which the entire personality of a person and your own personality make contact.37

Being involved with another entails not the loss of self but rather the positive charge of mutual polarisation. Understanding the meaning of the painting requires a sense of the painting’s autonomy, its totality, at the very same time it requires you to maintain a sense of your separateness, your totality. As Newman stated:

I hope that my painting has the impact of giving someone, as it did me, the feeling of his own totality, of his own separateness, of his own individuality, and at the same time of his connection to others, who are also separate. And this problem of our being involved in the sense of self which also moves in relation to other selves … the disdain for the self is something I don’t quite understand.38

To encounter a painting by Newman is to encounter a virtual entity that magnetises one’s relation to oneself around one’s relation to another. The meeting gives the mutual relationship structure.

Newman pondered the implications of the moment at which another entity appears to the self for the first time. When he remarked on ‘Adam’ meaning both ‘earth’ and ‘red’ with reference to the colour of the Brazilian soil, he immediately added: ‘And I bring this [definition] up for a real reason … my work, although it’s abstract … is involved in man.’39 What is the meaning of a painting? What is the meaning of another person? For Newman, the questions were intertwined:

The problem of a painting is physical and metaphysical, the same as I think life is physical and metaphysical. It’s no different, really, from one’s feeling a relation to meeting another person. One has a reaction to the person physically. Also I do believe that there’s a metaphysical thing in the fact that people meet and see each other, and if a meeting of people is meaningful it affects both their lives. And to be able to say what really affects both their lives, as we are trying to do here, is extremely difficult.40

Two people who see one another (not just look at each other) create an intersubjective totality. In a sense, they call for each other. Likewise, in Adam’s case, it is as if the addition of its central band were somehow motivated into its existence by the others in such a way that their mere adjacency is subsumed into a larger structure or continuum, a real relationship. The ‘elements’ simultaneously articulate that continuum as they (paradoxically) generate it: they ‘brin[g] each other to life’, as Newman once said of his fields and bands of colour. They are bound in their mutual self-definition by necessity. The elimination of contingency from the relations he produces is meant to affirm the totality or autonomy of the work of art. That, in turn, institutes Adam’s mode of pictorial address and gives us – each of us, as the separate viewers we are – the chance to understand the independent point of view that it projects.41 Think of the creation of Adam – not only the biblical first man, but also Newman’s painting – as a very special instance of seeing or meeting another person for the first time.

Before closing this discussion, some brief remarks on the stakes of this interpretation might be helpful. What I have offered so far is an account of meaning that progresses from the description of pictorial effects to the elucidation of the modes of address those effects institute. Technically and formally managing the mutual determination of effects and address within or against the conventions of the medium, one could say, was Newman’s way of creating the structures of beholding he envisioned as governing the artist-audience exchange. His construction of the standpoint he intends the viewer to assume in relationship to the work is fundamental to the meaning it holds. Grasping the content of his paintings – their human content – stands or falls on the viewer’s willingness to adopt the point of view Newman projects. Only then may the beholder be in a position to understand his expression.42 In elucidating this reciprocal possibility, formal criticism is an essential tool. For if we cannot convincingly describe what Newman’s paintings are – and thus what their pictorial effects are meant to be – we will remain unable to fathom their immanent meaning as creative expressions, as the real statements about the self, experience and history that they are. What the canvas is actually and materially, and how we experience it as an object, is something entirely different from what the painting is about, from what Newman’s creative proposition is in Adam.

As I have begun to suggest, it is clear that we will not find Adam (the painting) to be, in any conventional sense, ‘about’ Adam (the biblical figure). After all, Newman depicts neither the man nor any of the narrative devices traditionally associated with him. Indeed, the fact that he does not – or feels that he cannot – is symptomatic of an artistic and critical generation acutely aware that modernity had decisively disrupted the authority of traditional symbolism to guarantee publicly shared meaning.43 Yet painters of Newman’s cohort – and he was their most eloquent champion – nonetheless claimed a universal significance for their art. For instance, in a 1943 letter to the art critic E.A. Jewell of the New York Times that was written with Newman’s guidance, the painters Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko stated: ‘The point at issue [in the evaluation of abstract art], it seems to us, is not an “explanation” of the paintings but whether the intrinsic ideas carried within the frames of these pictures have significance.’ They added: ‘There is no such thing as a good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject-matter is valid which is tragic and timeless.’44 Clearly, there is a tension generated by asserting, in the same breath, the idea that a picture contains an ‘intrinsic’ meaning (as if the artist’s expression were independent of all conventions) but that it also reaches outwards to a ‘timeless’ meaning (something that is presumably open to the emotional and intellectual grasp of an audience who shares in the putatively universal conventions of expression). That conundrum is symptomatic of a seemingly paradoxical goal: to address one’s art to the intensely felt experience of the historical moment, but to simultaneously render one’s meaning open to others who do not share – or cannot share – that moment when it passes, as it inevitably will.45

It can be instructive to think about the tension we encounter, as contemporary viewers, between our expectations of a trans-historical symbolic meaning and what the painting delivers in its effects at any given moment in our experience. In the discrepancy between Newman’s titular reference (the Adam of Genesis) and the work of art’s structure of beholding (Adam the painting) we confront a methodological problem of great significance. How should our interpretation advance? Should we simply attend to the experience of effects, and treat the object as an occasion for our responses, however arbitrary they might be? Or should we endeavour to explain Newman’s canvas as the product of its historical moment by accumulating various kinds of empirical evidence, which tends to reduce our understanding of the work according to an inventory of its putative ‘causes’? In taking either approach, it would seem, we will have adopted a methodological standpoint that isolates Newman’s art. We either confine it to the past or to the solipsism of a present experience. It is this impasse that the formal criticism and interpretation of structures of beholding is meant to overcome.

Newman’s paintings are made in relation to certain conventions of the medium, which operate as the constraining limits and generative possibilities of expression within the medium of painting itself. Those conventions also provide us with a framework to evaluate the expression as valid – which is to say, they provide the criteria against which we accept or reject the artist’s work as embodying a meaning that transcends the local contexts of its production and reception. In other words, Newman (an agent from whom we are temporally and spatially remote) invites us, within and through his work, to occupy the place it projects, and thus to share in its authority, which is independent of the historically contingent factors to which we frequently appeal, as if by methodological default, in order to explain the work’s existence. But this is not to say that factors outside the work cannot help us interpret his meaning. Rather, it is to say that when we appeal to those factors, our account of them – like our interpretation of the painting itself – must proceed from how, or in what qualitative ways, they illuminate Newman’s intentions as an artist. Above all, we must not presume them to provide the ‘empirical’ grounds by which we somehow document Newman’s ‘metaphysical’ achievement.