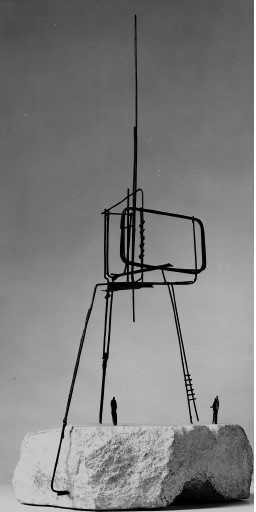

Fig.1

Theodore Roszak

The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952

Steel

371 x 476 x 229 mm

Tate N06163

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

American sculptor Theodore Roszak (1907–1981) produced this small sculpture in 1952 as a proposal for a monument on the theme of the ‘unknown political prisoner’ (fig.1). Submitted to an international competition organised by London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), and ultimately exhibited among other finalists at the Tate Gallery in March 1953, Roszak’s sculpture was one of almost 3,000 proposals from sculptors from around the world designed to ‘have commemorated all those unknown men and women who in our time have given their lives or their liberty in the cause of human freedom’.1 Made from welded and brazed steel, the sculpture is exemplary of the strangely modelled creatures that Roszak became famous for in the 1950s.

The acute angles of the work’s dominant elements evoke limbs, and its tough surface texture suggests the gnarled skin of a strange plant or animal. Such creaturely associations are further suggested by particular details of the work: curved barbs on the central horizontal element bring to mind thorns or the claws of a crustacean, while the inclusion of a finely rendered whiplash tail (or perhaps a vine) that curves around one leg also establish affinities to the natural world. The striding stance of the work gains a further sense of motion from the winged form that dominates its upper section, a baroque embellishment that appears to flutter as the sculpture thrusts forward, like a soldier entering battle.

Roszak’s proposal was first exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in January 1953, where it was selected as one of the American finalists for the international project. The competition had attracted 193 entries from across the United States, works that were judged by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie (MoMA), Daniel Cotton Rich (Art Institute of Chicago), Hans Swarzensky (Boston Museum of Fine Arts), Charles Seymour (Yale University Art Gallery) and Henri Marceau (Philadelphia Museum of Art).2 Roszak was notified of his inclusion in the exhibition in December 1952 but it was not announced officially until later. ‘For publicity purposes’, Ritchie wrote to Roszak, ‘it is very important that you do not reveal the fact that you have won this prize until January 28.’3

Along with this maquette, Roszak submitted nine photographs of the work, two drawings and one portfolio showing his other sculptures.4 In the MoMA exhibition of finalists, Roszak’s maquette was shown alongside the other finalist works by Calvin Albert, Alexander Calder, Rhys Caparn, Wharton Esherick, Herbert Ferber, Naum Gabo, J. Wallace Kelly, Gabriel Kohn, Richard Lippold and Keith Monroe. Each of these artists received a $200 prize for their work, but one critic singled out Roszak’s work for particular attention:

there’s no harm in ... guessing which might turn out to be the popular favorite. This last I guess to be Roszak’s contribution, and chiefly because he symbolizes freedom with a bird, and a handsome one at that. In the present small model in silvery bronze (I think), its sparkling texture is admirable, and, flung up to the ultimate size of 15 or 20 feet, it would enhance any park or public place likely to get it.5

A photograph of Roszak’s maquette displayed in the MoMA exhibition shows it to have been starkly profiled against a dark wall, its thrusting form pointing towards Calder’s more abstract, angular proposal.6 Along with many other participants in the competition, Roszak was photographed beside his entry, his four fingers resting on the sculpture as if to emphasise the bodily associations of its own gnarled steel limbs.

By March 1953 Roszak’s proposal was – along with the other American finalists – dispatched to London for the international exhibition at Tate Gallery.7 Roszak’s work was one of 146 entries from fifty-four countries featured in this exhibition. Attracting some 30,000 visitors to the museum from 14 March until 3 May 1953, the exhibition not only provided London audiences with a rich survey of recent work by major American sculptors (some years before the same was possible for painting), but also represented an early confirmation of the rapid internationalisation of modern art in the post-war years.8 Tate acquired seven of the works included in the show: by Antoine Pevsner, Luciano Minguzzi, Lynn Chadwick (who had each received prizes at the Tate exhibition), as well as works by F.E. McWilliam, Pietro Consagra, Emile Gilioli and Roszak.9

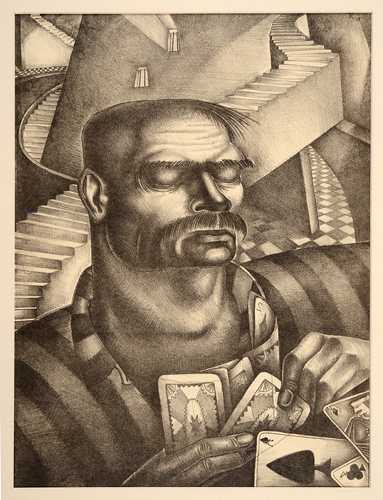

Fig.2

Reg Butler

Final maquette for The Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Tate L01102

© The estate of Reg Butler

As has been recounted elsewhere, the Tate exhibition was the subject of widespread controversy when the first-prize-winning work by British sculptor Reg Butler (fig.2) was attacked while on display.10 Furthermore, the anonymous funder of the competition reneged on their commitment to cover the costs of creating the full-scale monument, and Butler’s winning design was never realised. In an important 1997 article, art historian Robert Burstow established that the funding for the competition came through American philanthropist John Hay Whitney, who was acting as a conduit for the CIA.11 The fact that the initiative was supported by the CIA at the height of the Cold War represents, as art historian Joan Marter has pointed out, an ‘early incursion by the State Department in affirming the cultural supremacy of the United States and its Allies’.12 The politics that thus lay behind the competition are key to understanding the work Roszak produced and will be explored in more detail in the fifth section of this project, ‘Cold War Diplomacy’. At the time, though, the involvement of the CIA was a closely guarded secret and almost certainly unknown to Roszak, but he still seems to have grasped the ideological imperatives of the project.

Roszak’s statements on this work emphasise the socio-political importance of the subject for him. At the conclusion of the competition he wrote to ICA organiser Anthony Kloman to explain the work: ‘In thinking about the forms for the maquette, I was strongly motivated by the moral and social values implicit in the subject ... I envisioned the individual as politically committed either by accident or design again tyranny and oppression’.13 Roszak further explained that his work represented the inevitability of a social structure that validated individualism:

While we have history to attest to the endless forms of human incarceration as a reward for ‘sinning’ against the state, we have, nevertheless, witnessed the slow and hard won gains of those beliefs that have been sustained ... ultimately finding varying degrees of integration within the social structure. This clearly indicates to me not only the indication of an individual morality, but the force with which ideas break through, however belatedly, and triumphantly assert themselves on society as a whole.14

Fig.3

Barbara Hepworth

Maquette for ‘The Unknown Political Prisoner’ 1952

Tate T12026

Photo © Bowness

In emphasising the capacity for prisoners to stand ‘defiant in the face of oppression’, Roszak’s muscular, winged creature transformed the sombre theme into a wholly more optimistic one. As indicated by the words ‘Defiant and Triumphant’ in its title, Roszak’s sculpture does not so much represent the prisoner than it does emancipation from imprisonment, and in so doing, the victory of the individual over the oppressor. Here, Roszak followed the strangely celebratory tone of the competition documentation: ‘Sculpture is the art in which great themes have been traditionally expressed, and nations have always chosen this art to enshrine their highest aspirations or to commemorate their proudest memories’.15 While many of his peers proposed monuments to never-ending imprisonment, replete with variously abstracted evocations of chains and prison bars (see, for instance, Barbara Hepworth’s entry; fig.3), Roszak’s proposal complied with the more positive ambitions of the competition’s organisers.16

Roszak’s sculpture was, he explained in a letter to Tate director John Rothenstein, ‘designed and executed for the express purpose of meeting the conditions as set forth by the International competition’.17 In line with these guidelines, the work is smaller in scale than most of Roszak’s work from this period. His design did, however, consider the effect of its enlargement. ‘The sculpture winning the grand prize will be installed on some site of international importance, such as a prominent situation in any of the great capitals of the world’ explained the entry form. ‘Such a site can only be determined after the award has been made, and in relation to the style adopted by the sculptor, but the monument should be conceived as standing free, and independent of any architectural setting.’18 Roszak’s most richly rendered drawing of the monument (fig.4) shows his design towering over a barren landscape, an unidentified but dramatic context for his proposed monument.

Fig.4

Theodore Roszak

Study for Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Tate L03772

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Although its size and theme responded to the specifics of the competition, Roszak’s sculpture is also typical of – and closely connected to – the broader character of his sculpture made in the immediate post-war years. The work is constructed from steel, which was extensively welded and manipulated to create the distinctive textures of its surface. As art historian Donald Irving has explained of the artist’s technique more generally, Roszak used ‘steel rod, plate, wire, and other stock which was fused into a homogenous mass ... edges and surfaces were ground, filed and polished, adding a reflecting sparkle at carefully reasoned junctures’.19 Using an oxyacetylene torch, Roszak was able to treat metal as a malleable material so that it could be handled, as the artist once put it, ‘as easily as wax’.20 The result, as art historian Kenneth Sawyer described at the time, was a surface ‘often resembling cooled lava’.21

One of Roszak’s assistants, Anthony Padovano, has further explained that Roszak often ‘ground down brazed surfaces to achieve light catching pellets’.22 Unlike welding, brazing does not melt one metal to another, but rather bonds two dissimilar metals with a third bonding material, such as solder or brazing flux. An early black and white photograph of The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant), taken by Soichi Sunami and held in Tate’s archive (fig.5), shows that this lighter coloured brazing originally endowed the work with a more variegated and perhaps even reflective finish than it has now. Evidence suggests such changes in the surface effect of Roszak’s sculpture could occur quickly: in the case of his Sea Quarry 1950 (fig.6), the artist was asked to ‘recondition’ the piece only three years after it was first made, a process for which he ‘first removed the accumulated rust’ and coated ‘its surface with a strong film of lacquer to protect the metal from undue oxidation’.23

Fig.5

Soichi Sunami

Photograph of Roszak’s The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant), 1952

Tate Archive TGA 955/1/12/258

© Estate of Soichi Sunami/Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fig.6

Theodore Roszak

Sea Quarry 1950

Steel

775 x 965 x 648 mm

Norton Museum of Art, Florida

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

Roszak understood such techniques to align with social realities of the period in which he worked. In 1946 he wrote:

material which can be shaped at white heat and is subject to various nuances of chemical action is the best means for implementing this spirit embodied in the work of this period. Some people feel that technology is inhuman, but machinery is part of human thought. Look into the engine of a car – how wonderful it is, what precision, what order. It seems to me that artists who rebel against their times or go to the other extremes are both equally wrong. Artists are never rebels, nor can they escape into the future or into the past. Carving directly in stone – a big thing for sculptors in the ‘twenties’ and ‘thirties’ – was all right for medieval artists. For them it must have seemed a wonderful new thing. Working methods and materials should always be appropriate to the age in which the artist works.24

The material associations of Roszak’s sculpture are closely connected to the work of a wider range of post-war sculptors who also used welded steel, and for whom scorched metal was often understood to reference the bodily horrors of the Second World War and the anxieties of the nuclear age. In the United States, Roszak’s work was frequently connected to that of Seymour Lipton, Ibram Lassaw and Herbert Ferber. In its evocation of primitive ritual, sacrifice and violence, Roszak’s art equally bares comparison with aspects of David Smith’s more surrealist work of the 1940s such as The Royal Bird 1947–8 (fig.7). While some have sought to connect the turbulent forms and textures of their work to contemporary New York School painting, artists with whom Roszak did indeed have some contact, it is equally productive to understand such work in relation to the distinctly international development of welded sculpture in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Fig.7

David Smith

The Royal Bird 1947–8

Steel, bronze and stainless steel

562 x 1520 x 216 mm

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

© David Smith Estate/VAGA, New York, NY

In Europe, Roszak’s practice bares particular comparison to the work of César, Germaine Richier and especially Alberto Giacometti. Their flickering, almost painterly surfaces share affinities with the light-catching textures of Roszak’s post-war work, but also recall the earlier example of the French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). In 1953, for example, art historian Leo Steinberg connected the flickering finish of Rodin’s modelling and its tendency to turn ‘firm flesh into a symbol of perpetual flux’, to the equivalent sense of formal mutability in the work of sculptors including Roszak.25 A 1955 feature on the ‘Rodin Revival’ would name Roszak among those contemporary artists making use of the French sculptor’s painterly finish.26 In a postscript to the catalogue for the Rodin exhibition he curated at the Museum of Modern Art in 1963, Peter Selz observed that French sculpture had been able to be ‘seen with fresh eyes’ because sculptors of the 1950s had evidenced ‘a general predisposition in the direction of his [Rodin’s] freedom of form, so dependent on effects of light.’27

Fig.8

Bernard Meadows

Black Crab 1951–2

Tate T03409

© The estate of Bernard Meadows

For British audiences, Roszak’s post-war sculpture must have also resonated with the angular forms then popular among sculptors such as Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick, Elizabeth Frink and Bernard Meadows (see fig.8). Many of these artists had represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1952, and the acquisition of Roszak’s sculpture by Tate the following year helped confirm the international currency of their style. In his essay ‘New Aspects of British Sculpture’ written for the Venice exhibition, the critic Herbert Read famously coined the phrase ‘geometry of fear’ to characterise the work of these artists:

These new images belong to the iconography of despair, or of defiance ... Here are images of flight, of ragged claws ‘scuttling across the floors of silent seas’, of excoriated flesh, frustrated sex, the geometry of fear ... Their art is close to the nerves, nervous, wiry ... they have seized Eliot’s image of the Hollow Men, and given it an isomorphic materiality. They have peopled the Waste Land with their iron waifs.28

Although Read’s description concerned British sculpture, his account can also serve as a faithful description of what was properly a more global trend for mutated, eviscerated forms. Roszak was once among the most prominent practitioners of this style. By the end of the decade, however, such work had fallen out of favour, a shift that left a lasting impact on the reputation of Roszak and many of his peers. When artist Michael Ayrton reflected on the International Sculpture Competition in 1957, he could already criticise the dominant style as a kind of fad, one that saw artists following an ‘almost comically world-wide adhesion to a limited vocabulary of romantic forms’ such that ‘it would be possible to publish and circulate it internationally by means of diagrams’.29

Roszak was born in Wroclaw, Poland, in 1907, and moved to the United States at the age of two. He grew up in the Polish neighbourhood of Chicago and studied art and music from a young age. According to the artist’s daughter, the ten-year-old Roszak won a set of ice skates in a newspaper competition to draw a fire engine.30 He enrolled in evening classes at the Art Institute of Chicago as a teenager, and after finishing high school enrolled as a full-time student. In 1925 Roszak moved to New York where he studied at the National Academy of Design with George Luks and Charles Hawthorne, and took classes in philosophy at Columbia University, which undoubtedly informed the sophisticated references behind his work.

Fig.9

Theodore Roszak

The Jailor (The Prisoner) 1928

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

After returning to Chicago in 1927 Roszak began to teach drawing and printmaking at the Art Institute. One of Roszak’s prints from this period titled The Jailor (The Prisoner) 1928 (fig.9) suggests that the theme of the Tate maquette was one he had engaged with many years earlier. The grotesque distortions of Roszak’s figuration in such works already suggest an artist reaching beyond the then dominant realism of American art, even that of its most acerbic practitioners like Walt Kuhn and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. In Chicago, Roszak began to develop an interest in abstraction. He later recalled being impressed by the ‘enormous crescent shape’ in Arthur Carles’s Arrangement 1928, a colourful cubist still life that had been awarded a prize at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1929.31 The curved sickle shape in Carles’s picture would later become one of Roszak’s most characteristic forms.

In 1929 Roszak received a fellowship to study abroad and spent eighteen months in Europe. He travelled in France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Czechoslovakia, where he briefly established a studio in Prague. Roszak’s evident engagement with the painting of Giorgio de Chirico during this period is frequently remarked upon, but less noted is his work’s stylistic proximity to the abstracted machinery of influential Czech modernist Frantisek Kupka. Returning to the United States in 1930, Roszak settled in New York. In 1933 his work was included in the First Biennial of Contemporary American Painting at the Whitney Museum, which purchased his painting Fisherman’s Bride 1934 two years later (fig.10). Roszak participated in the Federal Art Project by teaching at the Design Laboratory, where the influence of Bauhaus émigré artists such as László Moholy-Nagy emphasised a constructivist integration of art, design and industry.

Fig.10

Theodore Roszak

Fisherman’s Bride 1934

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

Fig.11

Theodore Roszak

Bipolar in Red 1940

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

The work that Roszak produced at the Design Laboratory seems relevant to the vision behind The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant). ‘What particularly caught his imagination’, recounts art historian H. Harvard Arnason, ‘was the concept of the artist as an integrated and contributing factor in society, working together with the architect, the city planner, the sociologist, [and] the industrialist in the creation of a more harmonious world.’32 Such social ambitions were realised by the unification of sculpture with architecture in Roszak’s later public works. Works from Roszak’s Julien Levy Gallery exhibition in 1940 such as Bipolar in Red 1940 (fig.11) represent an important phase in his practice, and their startling dissimilarity from his more famous post-war sculptures should not be mistaken for artistic immaturity. As art historian David Wheeler has suggested, they represent ‘a fully, mature sophisticated art – a sleek Art Deco variant of Constructivism’.33

Roszak would later abandon such formal preferences. ‘The constructivist world assumes a complete interaction with life’, he explained in a 1952 talk at MoMA, including ‘all the accoutrements of scientific jargon and the attending products and by-products of technology’. To produce constructivist work meant, for Roszak, ‘to finally approve the present state of society’.34 Later, he would complain of a presentation of American painting and sculpture that placed it ‘on the same level with that of toasters and mixmasters’.35 These shifting views reflected less his anxieties about American materialism than it did the traumas of the Second World War. It was Roszak’s experience of war that produced a dramatic revision of his style. In 1945 Roszak himself explained his position in the catalogue for the Fourteen Americans exhibition at MoMA:

The constructivist’s position, historically, with its influence upon architectural and engineering design, has been and is an important one, continuing to have its effect upon artists and designers alike. At the same time that these ‘constructive’ purposes and intentions exist, the world is fundamentally and seriously disquieted and it is difficult to remain unmoved and complacent in its midst.36

Addressing this milestone statement two decades later, in the exhibition catalogue for Roszak’s retrospective, Arnason attempts to smooth over the dramatic shift in Roszak’s practice. ‘Has not the disquiet always been there ... Is it not present in the haunting mood of the paintings, in the menace of the machine constructions’ he asked, attempting to render Roszak’s artistic concerns as ‘basically unchanging’.37 Arnason’s conclusions explicitly counter the artist’s own account of a radical shift in his art, suggesting instead that ‘there is actually a much greater continuity and fixedness of purpose than he seems to admit’.38

For Arnason, the formal change was a more straightforward matter of artistic development. ‘By 1945’, explains Arnason, ‘he was beginning to feel restive under the severe geometric limitations of constructivism and to experiment with three sculptural shapes.’ Technical experimentation therefore serves to explain the transformation: ‘A desire to achieve larger forms led to experimentation with welding, and the welding process led to the discovery of fascinating effects such as the fretted surface, the nodules and tactile variations of welded metal.’39 Arnason further diminishes the shift by arguing for the underlying similarity of apparently divergent practices, a ‘unity of purpose, of idea and form which controls Roszak’s work ... whatever may be the stylistic variations and limitations he has set for the individual piece’. Such efforts to avoid the social contexts behind the dramatic rupture in Roszak’s practice might have sought to absorb his varied practice into the comforting continuities of monographic art history, but they also helped smooth over the historical specificities of his art.40

Even art historians favourable to Roszak have expressed their uncertainties about the inconsistencies of his style. Joan Seeman has regarded the year 1952 – and works including The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) – as the ‘terminal year’ of Roszak’s ‘original contribution’, suggesting that after this time he merely ‘elaborated themes and forms invented earlier’.41 From this time, she claims, his art became ‘over-extended and overwrought’.42 Art historian and curator Douglas Dreishpoon has, by contrast, defended the significance of Roszak’s later work.43 The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) points the way forward to Roszak’s large-scale monuments, works that still require further research.

Fig.12

Theodore Roszak

Raven 1947

Theodore Roszak Estate, New York and private collections

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

A useful barometer for the shifting reception of Roszak’s sculpture are the views of critic Clement Greenberg. In 1947 he regarded Roszak’s Raven (fig.12) ‘one of the strongest works of art ... ever seen turned out in this country’.44 Two years later, Greenberg named Roszak alongside artists including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and David Smith as representing the first genuinely American avantgarde.45 Greenberg even once owned a work by Roszak, but he appears to have sold the work later in life.46 However, when Greenberg began to view David Smith as the leading sculptor of post-war America, the painterly finish and existential thematics exemplified by Roszak (and championed by Greenberg’s critical adversary Herbert Read) would come to be banished from the American critic’s canon.47 As Dreishpoon has shown, the literary and romantic streak of Roszak’s post-war work came instead to appear ‘European and retardataire’ to Greenberg’s taste, antithetical to the purely formal interests he saw as the proper concern of modern American sculpture.48

Roszak, for his part, understood the debased position of modelling well enough to assert in 1949 that ‘modeling, to me, is a legitimate means of expressing sculptural ideas’, and that ‘sculpture today demands a medium embodying a combination of malleability and tensile strength exceeding the possibilities of both clay and stone’.49 Although Roszak did not deny that ‘accidents arising out of the characteristics inherent in the medium’ might enhance his sculpture, he preferred ‘to have an idea before working’.50 Here Roszak distances his method not only from the legacies of surrealist automatism but also from the rigid formulations of formalism. ‘I revolt against the persistent limitations implied by the dictating drive of the material itself’, he declared in 1955. The dominance of the ‘media alone’ or the ‘material itself’ – barely disguised swipes at Greenberg – ‘must be restrained and re-directed, not only within the area of the arts, but on all levels of society as well’.51 As always, Roszak’s project was loaded with social ambition.

Fig.13

Theodore Roszak

Spectre of Kitty Hawk 1946–7

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

Roszak’s failure to comply with such dictates did not, however, prevent him from experiencing substantial success in the post-war decades. In 1946 he was included in Dorothy Miller’s exhibition Fourteen Americans at the Museum of Modern Art, alongside artists such as Arshile Gorky, Mark Tobey, Robert Motherwell and Isamu Noguchi. MoMA director Alfred Barr also played a key role in promoting Roszak’s work during these years. Barr was on the judging panel that awarded his Spectre of Kitty Hawk 1946–7 (fig.13) the Logan Medal at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1950, and acquired the work for the Museum of Modern Art soon after. The sculpture was illustrated in Barr’s widely distributed book Masters of Modern Art (1954) and included in the museum’s touring exhibition Modern Art in the United States, which saw this major sculpture displayed at the Tate Gallery in 1956.

The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) was the first work of modern American sculpture to be purchased by Tate. Its acquisition followed a swift succession of museum purchases of Roszak’s work, including Thorn Blossom 1947 by the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1948, Spectre of Kitty Hawk 1949 by the Museum of Modern Art in 1950, and Young Fury 1949 by the Museum of Modern Art São Paulo in 1951, his first work to enter an international museum collection after it was awarded a purchase prize at the São Paulo Biennal. Despite not receiving an award for his entry to the competition at Tate, the purchase of Roszak’s maquette by the Tate continued this streak of high-profile acquisitions. ‘I regard the inclusion of my work to the collection of the Tate Gallery as of singular distinction’, he wrote to gallery director John Rothenstein in 1953, ‘and I want to express my gratitude ... for conferring on me this coveted honor.’52 Tate’s trustees gave permission for the work to be shown at Roszak’s retrospective at the Walker Art Center and the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art in 1956–7, but it has been exhibited infrequently since.

Fig.14

Theodore Roszak

Iron Throat 1959

Theodore Roszak Estate, New York

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

Although Roszak’s sculpture has now largely slipped from the post-war canon, his work might be seen in a new light by comparing it with increasingly celebrated sculptors of the 1960s whose work equally derives its force from hybrid figurative references and social charge. Lee Bontecou’s large-scale reliefs, for example, seem in sympathy with Roszak’s sculpture, while the steel constructions of Melvin Edwards more directly assimilate aspects of Roszak’s work.53 By the late 1960s, as the American art world again grappled with the human impacts of war, Roszak’s work acquired a new potency. For the 1969–70 exhibition Human Concern/Personal Torment, presented against the backdrop of the American War in Vietnam, Roszak’s Iron Throat 1959 (fig.14) was exhibited alongside more recent corpse-like grotesques by Bruce Conner, Daniel LaRue Johnson and Paul Thek. The exhibition catalogue quoted Roszak’s call to arms written almost twenty-five years earlier: ‘The world is fundamentally and seriously disquieted and it is difficult to remain unmoved and complacent in its midst’.54 It is a statement with recurrent relevance that serves to reassert the significance of Roszak’s art.