As The Man Phoning Mum makes clear, the cinema that appears in The Girl Chewing Gum is no longer there. After forty years in operation, the Dalston Odeon closed down on 31 March 1979. The building remained empty until 1984, when it was demolished to make way for the block of flats that currently occupies the site. One might find nothing particularly remarkable about the Odeon’s demise; after all, the same fate has befallen dozens of former London cinemas. However, there is a certain curiosity to the way in which its destiny both diverges from and points to the life The Girl Chewing Gum has led in the age of video. On the one hand, the Odeon and Smith’s film are nothing alike: the cinema is gone and forgotten, while the film has in recent years reached new heights of popularity and acclaim. But on the other hand, the disappearance of the Odeon indexes a notable feature of the contemporary existence of The Girl Chewing Gum: today, it is often found far from the movie theatre in the spaces of contemporary art, where it has entered new frameworks of distribution and exhibition.

Fig.1

John Smith

Shepherd's Delight 1980–4 (film still)

Courtesy the artist

In 1984, the same year the Odeon was razed, Smith made an initial foray into gallery exhibition when Shepherd’s Delight 1980–4 was selected for that year’s British Art Show, which toured to museums in Birmingham, Edinburgh, Sheffield and Southampton and was the first to include the moving image (fig.1). The thirty-five-minute long 16 mm film had been made for theatrical presentation and relies heavily on the start-to-finish trajectory and spectatorial attentiveness such a situation enables. As such, it did not fare very well when transferred to video, looped and shown on a small monitor with no seating provided. In the 1990s, however, the circumstances under which the moving image might be exhibited in art spaces began to change dramatically, principally due to the availability of data projectors and video formats of increasing quality. The decade witnessed an explosion of moving images in galleries and museums, one that occurred very much under the sign of cinema. Film historical references, engagements with illusionistic narrative, new documentary practices and a pictorialism never before seen in video predominated – all of which contributed to a situation in which ‘video art’ largely shed its ties to television and gave way to what would increasingly be called ‘artists’ cinema’ or ‘artists’ moving image’.1 Such a climate fostered new interest in the history of avant-garde film, introducing canonical works like The Girl Chewing Gum to different audiences. Historically situated at arm’s length from the art world, avant-garde film now appeared as a vast and rich archive that might be integrated into the gallery alongside newly emerging practices.

Fig.2

Installation view of John Smith's The Girl Chewing Gum 1976 at the sixth Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, June–August 2010

Courtesy the artist

The first appearance of The Girl Chewing Gum in a gallery context was in a group exhibition entitled Traffic, held at Curtain Road Arts in London’s Shoreditch from 11 April to 21 May 1997. A mixed programme of shorts was projected onto the main front window of the gallery at night, with the result that the films were visible from the street. Other artists featured in the show included Anna Best, Nicholas Bolton, Keith Coventry, Dan Graham, Graham Gussin, Ritsuko Hidaka, Hilary Lloyd, Sean Roe, Emma Smith and Michael Stubbs. The film was installed as a looped video projection for the first time at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham in 2003. These events inaugurated a new chapter in the film’s reception history, one in which it would show frequently in Europe and North America as a video installation, thus shifting its material substrate and its larger dispositif at once. A year of especially high visibility for The Girl Chewing Gum in the art context was 2010, when it was shown at the Armory Show in New York, the Kunsthall Oslo, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London, where Smith was the subject of an exhibition entitled John Smith: Solo Show curated by the students of the MA Curating Contemporary Art course. That year, the curator Jens Hoffman wrote in Frieze that the film was the ‘surprise hit’ of the sixth Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, while Artforum illustrated its review of the Biennale with an installation shot of the film, which had been accorded a space of its own in a vacant shop at Dresdener Strasse 19 (fig.2).2

On the occasion of the RCA exhibition, the critic Martin Herbert wrote that ‘John Smith’s films and videos have been criminally under-shown in his home city’.3 Certainly the increased attention from the art world has helped to remedy this, with the RCA’s Solo Show in particular bringing together twenty-two of Smith’s works. How might one account for this flurry of interest? One might see it simply as The Girl Chewing Gum belatedly getting the respect it has always deserved. But it is worth noting that the film also fulfils a desire that shaped much curatorial activity in the early twenty-first century. When the art critic and historian Hal Foster wrote of the ‘archival impulse’ in contemporary art, he was describing artistic practices that delved into and reactivated forgotten histories.4 But a related form of archive fever also struck curators during this period, as it became common for exhibitions devoted to contemporary art to include older works. Many curators rummaged through marginalised histories in search of major figures who might be presented to the mainstream art context as new discoveries. Although Smith counts as a firmly canonised figure in the history of avant-garde cinema, until recently he had been relatively absent on the gallery circuit – much like Anthony McCall, Paul Sharits and Morgan Fisher, figures of the same generation who received similar treatment during this period.

While there has been an overall reappraisal of Smith’s work in recent years, The Girl Chewing Gum has received by far the most attention. Its engagement with narrativity and documentary render it a particularly apposite precursor to the many contemporary works that seek to interrogate those very issues. The first decade of the twenty-first century was marked by a proliferation of moving image practices that actively interrogated cinematic conventions. Documentary in particular was taken up as a discursive field to be questioned, reimagined and pushed forward. If at the time of its production The Girl Chewing Gum had been somehow out of step with the party line of structural/materialist film by taking as the object of its reflexivity cinematic conventions rather than filmic materiality, some thirty years later this gesture resonated as absolutely contemporary.5

Fig.3

Installation view of John Smith's The Girl Chewing Gum 1976 at Tate Britain, London

Tate

© John Smith

Whatever the reason may be, it is clear that the exhibition of The Girl Chewing Gum in the gallery space comes with both disadvantages and advantages (fig.3). Many debates around the importation of historical avant-garde cinema into the gallery have revolved around the material transposition from film to video that is in the majority of cases a prerequisite due to the cost and fragility of exhibiting celluloid. Particularly in the case of filmmakers who engage reflexively with the material substrate, such format shifting can result in a betrayal of the medium-specific concerns of the film. For example, the meaning and integrity of a work such as Peter Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer 1960 – a black and white flicker film that extensively interrogates the single-frame articulation – would be severely injured were it to be shown on video. It is following this logic that Smith has declined to exhibit Leading Light 1975 and the silent version of Hackney Marshes – November 4th 1977 1977 digitally: both films are edited in camera and make use of flash frames that directly index the technological process of shooting photochemical film.6 The Girl Chewing Gum, however, does not run up against this difficulty, for it interrogates not the materiality of film but the conventions of cinema, which are relatively unaffected by medium change. This means that while the shift to video may impact the viewer’s phenomenological experience of the work, its meaning will not be compromised. Indeed, Smith has expressed that he now prefers to exhibit the film on video because it provides a more consistent, higher quality form of presentation due to how quickly film prints wear out and how easily projectors can slip out of focus. He is also keen to avoid the fetishisation of photochemical film that has been a major feature of artists’ moving image in the early twenty-first century, wherein the obsolete technology can become more fascinating to viewers than the film on display.7

What is potentially undermined when it is exhibited in the gallery is the film’s investment in a start-to-finish structure. Viewers can walk in and out of the space at any point in the loop, resulting in the strong likelihood that they will miss its passage from direction to fabulation or find out too soon that the narrator is positioned some fifteen miles away on Letchmore Heath. Smith has tried to mitigate this possibility by looping the film to commence every fifteen minutes, thus encouraging the viewer to encounter it from beginning to end. Morgan Fisher, a figure who has worked in both the cinema and in art contexts, has made a distinction between what he calls ‘teleological film’, which relies on a particular linear progression to create meaning, and works that may be encountered at any point and are thus amenable to display on loop.8 Fisher’s distinction does not rely on authorial intentionality – on whether or not the filmmaker originally intended the work to be shown in a gallery, cinema, or both – but rather on how the internal textual organisation of the work interacts with its screening context. There is no doubt that The Girl Chewing Gum is a teleological film in Fisher’s understanding of the term and thus would better be seen under conditions that would facilitate start-to-finish viewing. However, agreeing to exhibit it in the gallery means that it will be seen by a significantly larger number of people, thus perhaps making the migration into the art context worth the sacrifice.

The institutional relocation of The Girl Chewing Gum also brought changes to the distribution models it inhabits. In 2008 Smith took on commercial representation with Tanya Leighton Gallery in Berlin, at which time the gallery retroactively issued many of his earlier films, including The Girl Chewing Gum, as limited editions of five. A concept imported from printmaking, the limited edition reins in the reproducibility of the moving image through contractual means, artificially creating the kind of scarcity that will make it viable on the art market, which privileges uniqueness and rarity. This is, of course, a form of distribution very different than the rental model of the London Film-makers’ Co-operative and its successor organisation, LUX, which constituted the primary means of circulation for Smith’s films prior to 2008.9 In the rental model, the filmmaker deposits a print with a distributor, which then hires the work for a pre-set fee, returning a designated percentage to the artist. Any print sales that would occur under this model would be for the life of that print only. Smith agreed to edition his body of work on the condition that it would continue to remain available for hire and that he would retain the ability to publish it on mass market DVDs.10 This might initially seem to compromise the artificial rarity of the limited edition; indeed, some filmmakers have viewed the situation in this way and withdrawn their work from distribution agencies such as LUX or Canyon Cinema following the decision to edition it. However, Smith’s embrace of multiple, cooperating forms of distribution recognises that different formats serve different markets and different purposes. What is at stake in the editioning model is less the sale of a rare object and more a set of rights and permissions governing the present and future of the work. When Tate acquired The Girl Chewing Gum from the Tanya Leighton Gallery in 2010, the institution was making a long-term investment in the stewardship and preservation of the film – one that has very little to do with a widely circulating DVD copy, which is not an archival format and does not come with public exhibition rights.11

The Girl Chewing Gum continues to have a life not only within the broader context of contemporary art, but also within Smith’s own practice. In 2011 he engaged in a multi-part revisiting of the film that took the form of an installation called unusual Red cardigan, on view at PEER Gallery in Hoxton, east London, from 5 October to 10 December. The exhibition interrogated the space between the ‘then’ of filming The Girl Chewing Gum and the ever-shifting ‘now’ of its reception over time. It proposed that the temporal frame of the film must not be understood as limited to those moments in 1976 when it was first made or first shown, but must be expanded to encompass its subsequent circulation and reception. In line with the autobiographical thrust of much of Smith’s recent work, the exhibition explored the place that The Girl Chewing Gum has occupied in the life of its maker over the course of the thirty-five years since its production.

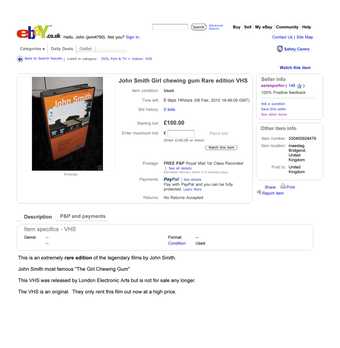

Fig.4

eBay listing posted by serenporfor showing 'John Smith Girl chewing gum Rare edition VHS', February 2010

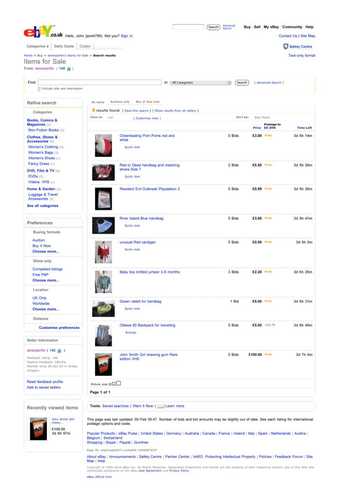

Fig.5

eBay listings posted by serenporfor including 'John Smith Girl chewing gum Rare edition VHS', February 2010

The germ of the installation came from a peculiar experience Smith had while Googling himself: he found a VHS compilation of his films, including The Girl Chewing Gum, for sale on the auction and shopping website eBay with a reserve price of £100 – quite an amount for an uneditioned tape, but perhaps justified by the fact that no other compilation of his films was available at the time and the VHS in question was out of print (figs.4 and 5). Smith became fascinated by the seller, a user named serenporfor who was located in Maesteg, a small town in Wales. Browsing through the other items serenporfor had for sale, Smith found that his VHS tape was quite anomalous; most of what was on offer were items of clothing, including a green rabbit fur handbag and an ‘unusual Red cardigan’. Smith attempted to buy all of the items that were up for auction, except for the final listing, ‘John Smith Girl chewing gum Rare edition VHS’. He succeeded in purchasing four of them: a backpack, the rabbit fur handbag, a baby’s knitted cardigan and – of course – the unusual red cardigan. At PEER, Smith installed his acquisitions within the space of the gallery, contextualising them with large prints of screen grabs from eBay and a text detailing the episode (fig.6).12

Fig.6

Installation view of the objects purchased from eBay by John Smith in the exhibition unusual Red cardigan at PEER Gallery, London, October–December 2010

PEER Gallery

Courtesy the artist and Chris Dorley-Brown

Fig.7

Photographic enlargement of the face of the girl from John Smith's The Girl Chewing Gum 1976, as shown in the exhibition unusual Red cardigan at PEER Gallery, London, October–December 2010

PEER Gallery

Courtesy the artist

Although serenporfor’s VHS tape contained a handful of Smith’s other films, The Girl Chewing Gum was the only title mentioned in the eBay listing. The film’s canonical status provokes some ambivalence in its creator: as Smith revealed in a wall text, ‘When I meet people who associate me with a work that I made 35 years ago and ask me “Do you still make films?” the popularity of The Girl Chewing Gum feels like a mixed blessing’.13 However, despite giving rise to such conflicted feelings, in unusual Red cardigan the extended life of the film became a memory trigger that opened a space for personal retrospection. Near the wall text was an extreme enlargement of a portion of one frame from the film: the titular girl’s face, grainy from magnification (fig.7). When Smith embalmed the contingencies of a Dalston afternoon in 1976, this woman unwittingly played a starring role. Does the girl who walked down Kingsland Road that day have any idea that she is the girl chewing gum in the film? In the same text Smith mused,

The people who happened to pass through my camera’s field of view one grey afternoon in Dalston 35 years ago have become very familiar to me now and feel like old friends. The Girl Chewing Gum herself must be at least 50 years old, probably a grandmother. I wonder what clothes she wears now, whether she still chews gum and whether she, like myself, still lives nearby. Maybe we pass each other in the street.

I wonder what her name is.14

The girl and serenporfor converged for Smith as two anonymous figures known only by their aliases. Incidental yet essential, they remain enigmas beyond their appearances in Smith’s work, perhaps unaware of the roles they play. They became the twin protagonists of unusual Red cardigan, serving to enlarge the temporal frame of The Girl Chewing Gum to include both the unknown futures of all who appear within it and the many unknown viewers who have encountered it over the years in its various release formats.

Fig.7

Installation view of monitors showing remakes of John Smith's The Girl Chewing Gum 1976 in the exhibition unusual Red cardigan at PEER Gallery, London, October–December 2010

PEER Gallery

Courtesy the artist and Chris Dorley-Brown

The second and third components of the exhibition furthered this interest by making recourse to one of the great preoccupations of recent artists’ moving image: the remake. The remake is a form marked by an internal schism in that it both invokes the original and asserts a distance from it. It invariably gestures to the past, creating a temporal space that extends from the present moment of remaking back to the original’s date of production, encompassing all that lies between. Next to the frame enlargement of the girl chewing gum in the show was a cluster of nine monitors showing numerous homages to The Girl Chewing Gum that have appeared online (fig.7). Each had headphones attached, but it was not immediately clear which set of headphones matched with which monitor, thus compromising the autonomy of any particular video and creating a set of relations between the multiple screens. With titles like The Guy in the Fluorescent Jacket, these remakes replay the conceit of Smith’s film for a number of different purposes: a university assignment to copy an artist’s work, a test of a 7D digital camera, or just for fun. Some are relatively straightforward, while others attempt a more clever play on the original, such as Emma Barltrop’s Chewing the Girl’s Gum 2011, in which the artist projects Smith’s film on a wall and writes over the image with a crayon in an effort to name everything that appears onscreen. Lurking amid these homages was a copy of the original film found online, albeit one that was both subtitled and rather poor quality, as it had been rephotographed off a television screen when it was broadcast in France. Like the story of serenporfor’s VHS tape, this section of the exhibition engaged with the distribution of The Girl Chewing Gum by means of secondary formats primarily intended for home viewing. If the new presence within the art space has been the most conspicuous of the film’s contemporary travels, Smith’s assembly of remakes points to another facet of its circulation, one that did not exist at the time of its production but which has played a significant role in the reception history of The Girl Chewing Gum: the networks of digital dissemination.

The final element in this constellation was Smith’s own remake, The Man Phoning Mum. Smith is far from the only avant-garde filmmaker of his generation to return to his best known film to produce a digital remake: in 2003 Michael Snow remade Wavelength 1967 as WVLNT (Wavelength For Those Who Don’t Have the Time), while in 2010 Anthony McCall remade Line Describing A Cone 1973 as Line Describing A Cone 2.0. But in these latter two cases, the concern lies primarily in the medium-specific differences between film and video (although questions of temporality and attention are also important for Snow). Quite differently, in The Man Phoning Mum – as in the rest of unusual Red cardigan – what is at stake is not only the analogue/digital divide but also autobiography and historicity. The Man Phoning Mum telescopes the Dalston of 1976 and the very different Dalston of 2011, recasting the original as an historical document.15 If the group of remakes found online and shown in the installation points to the place of The Girl Chewing Gum in film history, The Man Phoning Mum builds upon this to examine the 1976 film as history tout court.

The unusual Red cardigan installation charts the migration of The Girl Chewing Gum across media (16 mm film, VHS, television, digital video), across spaces (cinema, gallery, the internet) and also – crucially – across the bulk of Smith’s life, from age twenty-three to age fifty-nine. Art historian David Joselit has recently emphasised the ‘need to write histories of image circulation’.16 The exhibition might be understood as taking up this call, as Smith returns to his own film to trace out the multiple and sometimes unlikely pathways it has taken since its creation. He understands The Girl Chewing Gum not just as an immaterial representation that exists on a plane separate from reality, to be considered only within the restricted framework of the aesthetic, but also as a thing with a life in the world. This thing is part not only of the histories of art and cinema, but material and personal histories as well. unusual Red cardigan is a strange kind of retrospective in that it contains none of the artist’s earlier works (at least not in their original form) and yet functions as an idiosyncratic reflection on a life, a career, and on the film that marked both most deeply. Almost forty years after its making, The Girl Chewing Gum continues to resonate for its maker and its variegated audiences in new and unforeseen ways, proving that avant-garde film can be funny, critical, autobiographical, and historical – all at once.