Hans Hofmann’s Pompeii 1959 (Tate T03256) met its first viewers in January 1960, at the Samuel Kootz Gallery in midtown Manhattan, as one of several slab paintings in the exhibition Hans Hofmann: Paintings of 1959. Five months later, Pompeii voyaged across the Atlantic to the 30th Venice Biennale, where, alongside works by Franz Kline, Philip Guston and Theodore Roszak, it represented the United States to European viewers in the exhibition Quattro Artisti Americani: Guston, Hofmann, Kline, Roszak (fig.1). A photograph taken at the exhibition shows Hofmann and Toshimitsu Imai, among others, talking in front of Hofmann’s Pompeii and Indian Summer 1959 (University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley) (fig.2). Pompeii thus journeyed from one centre of art world power to another: from New York, the post-war locus of modern painting – at least according to Americans – to the Venice Biennale, an international theatre in which the political dimensions of national art styles and competition played out. Two years later, Pompeii went to Europe again, this time to the artist’s native Germany as part of a ten-month travelling retrospective through the country that was organised by the Fränkische Galerie am Marientor, Nuremberg. In 1964 Pompeii embarked on its third global trip, travelling with a retrospective organised by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. This time the painting’s voyage was hemispheric as well as transatlantic: the exhibition visited Buenos Aires and Caracas before journeying to Amsterdam, Turin and several cities in Germany.1 With the exception of its three-week debut at the Kootz Gallery in January 1960, Pompeii’s early public life took place entirely on foreign shores.

Fig.1

Title page of Quattro Artisti Americani: Guston, Hofmann, Kline, Roszak, exhibition catalogue, 30th Venice Biennale, Venice 1960

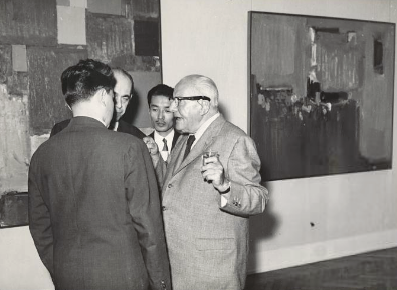

Fig.2

Agenzia D’Attualita Fotografia di Marzollo

Hans Hofmann, Toshimitsu Imai, and others at the Venice Biennale 1960, with Hofmann’s Pompeii 1959 and Indian Summer 1959 in the background

Hans Hofmann papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., bulk 1945–2000

Pompeii’s travels

American artists had long cast anxious glances eastward to their European counterparts, by turns admiring and rejecting the established traditions of England, France, Italy and Germany. But by mid-century they did so with a greater sense of confidence – or, depending on one’s perspective, chauvinism. American critic Sidney Tillim’s comments on the 30th Venice Biennale are typical in this regard. Looking at Americans Hofmann and Kline beside Europeans Jean Fautrier, Hans Hartung and Emilio Vedova, Tillim wrote that the biennale offered up an ‘incontestable conclusion: that American “Action” painting best demonstrates the iconoclastic character of postwar abstract art’. This conclusion was contested by Europeans, however, including the judges in Venice; Tillim noted the ‘reserved and even hostile’ response to American gestural abstraction in Europe, and described the biennale’s ‘official resistance to the unexpected challenge by the Americans to European, and particularly French, supremacy in art’.2

Claims to national cultural supremacy took on a renewed political valence during the cold war years, as nations jockeyed for influence in the new international order. As many have noted, US cultural policy – through entities such as the US Information Agency and MoMA’s International Program – utilised abstract expressionism as a symbol of freedom, both economic and political, in the cultural war between capitalism and communism in these years, underwriting exhibitions of American art in European countries.3 Such efforts can also be viewed through the lens of a broader American cultural imperialism, and the promotion of American business interests abroad. When Pompeii and several other Hofmann paintings journeyed to Argentina and Venezuela in the 1964 MoMA exhibition, it was within the ambit of President John F. Kennedy’s short-lived Alliance for Progress, a successor to the Good Neighbor Policy that sought to strengthen ties between Latin American countries and the United States.4

We can see Pompeii as an emphatically national object in such circuits: a banner for American individualism, cultural accomplishment, or general goodwill. Yet a full account of Pompeii’s international meanings would have to move beyond US policy and take into account the complex cultural and political webs on the ground in these various locales. In her study of gestural painting at the Venice Biennale, for example, art historian Nancy Jachec argues that gestural abstraction was incorporated into existing paradigms that read it not as American individualism but rather as a universal language, native to Europe and its Atlantic partners, that could facilitate transnational communication and integration in the increasingly global world order.5 In a similar vein, cultural historian and theorist Claire F. Fox advocates a ‘multilateral approach to the study of cultural policy’ in the cold war Americas. The ‘sheer complexity of the hemispheric art worlds’ in these years, and ‘the capaciousness of visual art to signify differently across time and space’, she notes, ‘sometimes resulted in unusual or unpredictable alliances that diverged significantly’ from the agendas of state officials or bodies.6 Perhaps the bright colours and floating slabs of Pompeii signified not an American idiom but a global Esperanto. Or perhaps its national meaning was complicated by Hofmann’s own international background.

Hofmann’s transnational career

A further story lies behind Pompeii, and that is Hofmann’s own life and career as an artist moving across borders – as traveller, expat and eventually immigrant. Born in 1880 in Weissenberg in the German state of Bavaria, Hofmann came of age as a painter within the international circles of artists who moved around central and western Europe in the years before the First World War. When Hofmann was six years old he and his family moved to Munich, where he would go on to study within the ‘lively Munich tradition of private painting schools, many of which were led by Eastern Europeans’, and which ‘often fostered a foreigner’s outsider, anti-establishment stance’.7 At the age of twenty-two Hofmann travelled to Hungary to paint with a summer artist colony in Nagybánya; the ‘rudimentary Expressionism’ of his Hungarian teachers, along with their emphasis on landscape, would prove formative for the young artist.8 In 1905 Hofmann moved to Paris for what would become a decade-long stay in the city, spent among the circle of German-speaking Henri Matisse followers at the Café du Dôme in Montparnasse. Yet the internationalism that had thus far provided fertile ground for Hofmann’s cultural and artistic development would be disrupted by the outbreak of the First World War: on vacation in Germany in summer 1914, Hofmann found himself unable to return to the life he had built for himself in the French capital. His early paintings, left behind in his Paris apartment, would never be recovered.

Fig.3

Unidentified photographer

Vaclav Vytlacil, Ernest Thurn and Hans Hofmann c.1926

Worden Day papers, 1940–1982, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

When Hofmann resettled in Munich in 1914, he embraced a pedagogical approach that reflected his own education in the German, Hungarian and French art worlds. He opened the Hans Hofmann Schule für Bildende Kunst in 1915, which attracted ‘an international array of students seeking more avant-garde instruction’ than that available at Munich’s more conservative Academy of Fine Arts.9 The curriculum included summer painting trips to Bavarian locations like Murnau and, later, to sites in Eastern Europe, Italy and the French Riviera. In 1930 temporary teaching gigs in California brought Hofmann to the United States for the first time, and in 1933 he moved there permanently. Yet Hofmann’s connections to Germany and to Europe persisted. While in Munich he had gained a following of American artists studying abroad, several of whom reconnected with their teacher in the United States – see, for example, the photograph of Vaclav Vytlacil, Ernest Thurn and Hofmann together from around 1926 (fig.3).10 By the time of Pompeii’s global travels in the early 1960s, Hofmann occupied a complex role with regard to his national identity. On the one hand, critics frequently read his work through his European origins. They cited Matisse and his time in the French capital, or, in the case of Tillim, they noted traces of ‘a native Gemütlichkeit’ in his painting – a somewhat untranslatable German word meaning geniality or warmth.11 On the other hand, Hofmann was cast as quintessentially American, enough of a national figure to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale. If the extent of Hofmann’s international travels – from Munich to Hungary to Paris to New York – was extreme, it was not, at its core, unique. Many of the abstract expressionists were immigrants who remade themselves – either intentionally or in the public’s view – as Americans.

Fig.4

Hans Hofmann

Effervescence 1944

University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley

© The estate of Hans Hofmann

One concrete manifestation of Hofmann’s transnational career is the language he developed to describe and teach visual art. Beginning in the 1940s, his formerly straightforward titles (still life, nude, landscape) blossomed into colourful and frankly bizarre formulations. Effervescence 1944 (fig.4) bubbles up drips and a liquid splash of neon magenta, echoing its name, while Fantasia 1943 (University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley) supplies an evocative if outlandish descriptor for its thickly brushed colours and skipping line of dribbled white paint. Other titles render words in strange combinations or with odd endings: Crystallic Constellation 1945, Delightsomeness 1956, Brillianter (More Brilliant) 1957 and Hilarious Splendour 1961 (all in private collections) each evoke boldness and joy, but in an awkward, stumbling manner. In Smaragd Red and Germinating Yellow 1959 (fig.5), Hofmann modifies his nouns as though to clarify them, but succeeds mostly in emphasising their opaqueness. What does it mean for a red colour to be ‘smaragd’ – the German word for emerald, and a rarely used synonym for the word in English? ‘Germinating’ suggests fecundity or growth, but the gerund sits oddly as a modifier for ‘yellow’. What does it mean for a yellow to be ‘germinating’ here – is the yellow bar in the composition’s centre latent with some imminent change?

Fig.5

Hans Hofmann

Smaragd Red and Germinating Yellow 1959

Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

© Estate of Hans Hofmann/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Some surely found such phrases embarrassing or strange – there is a hint of this in Tillim’s observation that Hofmann could not ‘repress a native Gemütlichkeit’ in his paintings.12 Yet in general the effusive and awkward translation of Hofmann’s language was effective because it underscored Hofmann’s role as translator more broadly. Hofmann was not just translating from German to English; he was widely seen as a translator from older generation to younger, from pre-war to post-war, and from Old World to New. Most importantly, his art (and teaching) was structured around a particular operation, the laboured translation of emotion into form. ‘Smaragd red and germinating yellow’ might be awkward grammatically, but it evokes a sense of the eruptive power and emotional resonance of colour. It is as though we can feel the artist searching for the right cognates in paint (and in words) for a concept that he has grasped only intuitively. The title Pompeii – which Hofmann rendered variously as Pompey and Pompei – works in a similar fashion. Like other place names used as titles in Hofmann’s oeuvre (Agrigento, Shangri-La, Mecca), Pompeii names a site that is far away in both time and place.13 Standing before the painting, we attempt to translate the forms in relation to the idea named in the title, to match the aqua-blue passage or the floating slabs to the landscape or architecture or classical ideal of the lost city. In Hofmann’s usage, the title points less to the real location than to a set of associations or memories set up in the artist’s and the viewer’s mind.

Varieties of expressionism

The efforts of translation involved in Hofmann’s various titles thus lead us to a final issue worth considering, namely the artist’s relationship to expressionism – indeed, to two different national expressionisms, one coded German and the other American. Hofmann’s social and professional networks put him into loose dialogue with German expressionism in the pre-war years: he showed in the Berlin Secessions of 1908 and 1909, and in 1910 he participated in a two-person show with Oskar Kokoschka at the Paul Cassirer Gallery in Berlin.14 He was friendly with German expressionist Gabriele Münter and, although he did not know him personally, was influenced by the writings of artist and theorist Wassily Kandinsky.15 Through these and other sources – fauvism, his Hungarian teachers in Nagybánya, strands of German empathy theory – Hofmann crafted an expressionist approach to art that prioritised the emotional resonances of form. Form ‘receives its impulse from nature’, Hofmann wrote, ‘but it is nevertheless not bound to objective reality; rather it depends to a much greater extent on the artistic experience evoked by objective reality’. What matters is not truth to nature but ‘the spiritual translation of inner concepts into form’.16 Thus Pompeii may receive its ‘impulse’ from nature and the outside world (it names a place), but it is not ‘bound’ to an image of the city; instead, the painting shows ‘the artistic experience evoked by’ the place name.

Hofmann’s theory of art would find its most elaborate explication in Sheldon Cheney’s Expressionism in Art, an influential text first published in 1934 and released in revised editions in 1948 and 1958. Cheney looked to a variety of sources in building his theory, from writer and collector Albert Barnes to philosopher Henri Bergson to sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand, but he noted that his ‘largest debt’ was to ‘Professor Hans Hofmann. It was the study of his two articles in The Fortnightly, doubtless, and the reading of a part of his unpublished work on Creation in Form and Color, that crystallized in its present form my “theory of plastic orchestration”’.17 Cheney writes of being ‘able to feel the structural line, in a Cézanne Mount Sainte Victoire, or a Giotto Lamentation, or a Kandinsky improvisation’, a phenomenon he compares to ‘the ability to “hear” the architectural relationships underlying the counterpoint of a Bach fugue’.18 The expressionist artist tries to get ‘to the soul of the object’ he paints, to find its ‘hidden essence’.19 ‘Expression in … art’, Cheney concludes, ‘has found its source at once out of the soul of the object and out of [the artist’s] own intuitive visioning’.20 In his own writings, Hofmann likewise stressed this relationship between artist and object, or between artist and the world outside. ‘The magic of painting’, he wrote in a 1955 essay, lies in ‘the harmony of heart and mind in the capacity of feeling into things that plays the instrument’.21 He adds later in the same text, ‘Quality … can only be produced through an act of empathy, that is, the power to feel into the nature of things’.22

The pantheistic, empathic expressionism of Hofmann, with its roots in pre-war Europe, is a very different beast from the abstract expressionism with which he would become closely associated in the post-war United States. While certain threads do indeed connect pre-war European expressionisms and mid-century abstract expressionism,23 the two movements propose very different models of the self. As art historian Michael Leja has written, for American abstract expressionists, ‘The subjects of the artist were the artists as subjects’.24 For Hofmann, by contrast, the self is there not so much as a subject but as a mosaic of memories, perceptions and emotions, themselves merging with elements of nature or painted form. Paintings like Pompeii do not offer up the self, realised, but rather point to a whole translational process of adequation between nature, emotion and form. There is more ‘soul’ or ‘spirit’ – more detached, free-floating emotion and empathic projection – in Hofmann than there is a striving or turbulent self-seeking to realise traces of itself in the visible world. Certain assumptions (about the primacy of emotion or the need for authenticity) underlie both forms of expressionism. But these assumptions are turned to very different ends. Unlike Jackson Pollock’s drips, marking out the artist’s movements, or Franz Kline’s slashing black swathes of paint that suggest an autograph of the self, Hofmann’s paintings rarely, if ever, signal his ‘presence’ on the canvas, or his coming-into-being amid a dangerous and chaotic world.