By the early 1960s – so the traditional art historical discourse goes – New York had already long defeated Paris as the new world capital for avant-garde art. As early as 1940, in the midst of war and German occupation in France, the art critic Harold Rosenberg had declared ‘the Fall of Paris’ in favour of a newly active American art scene.1 In opposition to a discussion of the ‘triumph of American art’ (Irving Sandler) in terms of formal innovations and aesthetic superiority,2 the art historian Serge Guilbaut famously demonstrated, in his seminal book How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art (1983), how abstract expressionism benefitted from the political and ideological conditions of the cold war to impose itself internationally in the late 1940s and early 1950s. ‘The French capital’, Guilbaut writes, ‘was not strong enough, either economically or politically, to protest. Momentum was all that Paris had going for it’.3 In 1961 Rivers was a renowned painter, and had been acclaimed by the most influential critics and supporters of abstract expressionism, such as Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg.4 What was he then doing in Paris in 1961–2? Should we consider his exhibitions in Paris and London in April–May 1962, when Parts of the Face: Vocabulary Lesson 1961 (Tate T00522) was exhibited and bought, as mere steps in the conquest of Europe by New York artists?

A recent trend in the history of art has sought to add a layer to our understanding of the internationalisation of American art by putting an emphasis on the role of local actors and situations. In her book The Great Migrator, art historian Hiroko Ikegami traces the international travels of Robert Rauschenberg in the early 1960s in several cities, including Paris. She seeks to distinguish her narratives both from the patriotic accounts of Rosenberg and Sandler and from revisionist ideological critiques such as Guilbaut’s, by paying attention to the complex interchanges between Rauschenberg and the local communities in which he was hosted. By taking a close look at specific dialogues, collaborations and works of art, she pictures ‘the global rise of American art as a reciprocal, cross-cultural, and yet necessarily conflicted process rather than as a result of unilateral cultural imperialism’.5 Adopting a far-reaching, ‘geopolitical’ view of American art, Catherine Dossin studied its internationalisation in her 2015 book The Rise and Fall of American Art in terms of concrete, localised artistic exchanges between American and European actors, with special attention drawn to economic factors and market conditions. While the scope is broad and the approach often quantitative, in Dossin’s words ‘This book is far more concerned with the active role of individuals than with ideology because its object, the art worlds, does not exist beyond the players who participate in it and make it’.6

This essay will build on this literature on the internationalisation of American art in the 1960s to account for Rivers’s participation in the Parisian scene in 1961–2. Archival evidence will be used to demonstrate that the painter’s stay in France was strategically planned to inaugurate a new phase in his international reputation and success, and that it was indeed a decisive step in his career. However, this was achieved in spite of – or rather, thanks to – Rivers’s refusal to follow his dealer’s advice to ‘not get involved emotionally with too many things or people’ in Paris. On the contrary, Rivers’s engagement with the 1960s Parisian cultural scene allowed him to nurture a new phase in his art, of which Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson is one of the keystones. Rivers’s close collaboration with Parisian artists therefore had an enduring impact, both on his own career back in the United States, and on the local French scene.

A career turn

Rivers’s decision to move to France in 1961 was decidedly planned as a career move. As the artist recalls in his autobiography:

Back in New York in the early spring of ’61, I was preparing a show for the Tibor de Nagy Gallery when I began to hear from two European dealers asking if I’d be interested in showing at their galleries. One was Charles Gimpel of Gimpel Fils, London, wondering if I would have enough uncommitted works for a show in the middle of May ’62. I was definitely interested in his interest. The other dealer was Jean Larcade in Paris, who ran Galerie Rive Droite, home of the ‘nouveaux realists.’ We decided on an exhibition to begin in April.7

In fact, as early as January 1961, Georges Marci, an important French dealer working for Galerie Rive Droite in Paris, where he was preparing a Jasper Johns show, wrote to Rivers with an explicitly strategic proposal: ‘I think if we could organise a good European group of shows you will be able to raise your prices in New York the following year’.8 He mentioned Gallery Schmella in Düsseldorf, as well as Gimpel Fils in London – two galleries then very active in a network of Western European avant-garde art. This proposal was surely attractive to Rivers. Although quite well known and favourably discussed by critics, he still felt insecure about his irregular sales and low prices, a recurrent subject of tension with his dealer and friend John Myers, co-founder of Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York.9 The success of Rauschenberg’s show at Galerie Cordier in Paris in April 1961 may have further convinced him that this was the right career move. In his letter Marci insisted, however, that Rivers’s step into the European art scene should remain purely professional: ‘Just do not get involved emotionally with too many things or people and stick to painting. That is what you are here for’, he commanded.10

Throughout the following months, Marci worked hard to prepare for Rivers’s arrival in Paris and to ensure his subsequent success. ‘I am trying to arrange shows for you in all Europe’, he wrote in March 1961, ‘and would like to handle not only your work commercially but do the kind of public relations that I do for Yves Klein in museums and magazines of Europe’.11 Indeed, Marci hurried to present Rivers’s work to ‘a prominent English critic named Lawrence ALLOWAY’ – none other than the inventor of the name ‘pop art’, and one of its earliest advocates in Europe and the United States.12 This allowed Rivers to be one of the first American painters associated with the movement: on the occasion of his show at Gimpel Fils in May 1962 he was invited to give a talk at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, and to be involved in a discussion with ‘the “pop” painters in the audience’, as one journalist reported.13

Marci’s most vehement efforts, however, were exerted to win the support of the art critic Pierre Restany, the nouveaux réalistes’ famous defender: ‘He is considered the most important in France’, Marci wrote, ‘and I spent three and a half hours showing him your works and discussing your ideas’.14 Interestingly, benefitting from Restany’s influence might have been a reason why Rivers was so eager to take French lessons upon arrival in Paris in the autumn of 1961 – resulting, as demonstrated earlier in this In Focus, in Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson.15 Indeed, Marci explained to Rivers that the very well-connected Restany ‘is with the “Radiotélévision francaise”, so I want you to work very hard on your French. We are going to do an interview on the French Television for you and also show paintings. I would like however for you to be calm rather than fluent in French as these art broadcasts reach a very wide range of audience.’16

Fig.1

Still from the television programme ‘Enquête: Paris est-elle toujours la capitale des arts?’ (‘Is Paris Still the Art Capital?’), broadcast on Radiodiffusion-télévision française, 23 September 1960

Archive of the Institut national de l’audiovisuel, Paris

Until 1963 there was only one unique television channel in France, which was controlled by Radiodiffusion-télévision française (RTF), under the supervision of the Ministry for Information. The impact of this monopolistic, state-controlled media was therefore not negligible, all the more so as cultural shows constituted an important segment of the programme contents. Restany, who had worked for the French government in the 1950s while he was becoming famous as an art critic, appeared regularly on French television in prime time shows.17 In July 1961, for instance, a sequence of Niki de Saint Phalle’s shooting paintings (or Tirs) in Restany’s Galerie J was included in the midday news.18 For Rivers, Marci probably had in mind the kind of interviews of artists in their studio that Restany conducted in a self-indulgent show entitled ‘Is Paris Still the Art Capital?’, broadcast in 1960 (fig.1).

Although the programme’s title bears a question mark, the answer is clear from the very first words of the show’s anchor, Jacques Mousseau, in dialogue with Pierre Restany: ‘Yes, Paris is more than ever the capital of genius and invention. Should we ourselves doubt this, the foreign artists living in Paris don’t.’19 The following six interviews of foreign artists in their Parisian studios – among them two Americans: the abstract painter Paul Jenkins and the sculptor James Metcalf – were therefore meant to demonstrate the appeal that Paris, supposedly, still prominently exercised on artists worldwide. That each of the artists spoke French in these interviews was key to emphasising the acculturation of these strangers and their passion for their host country.

Rivers’s stay in Paris was planned as a strategy of conquest, yet this was done with the active efforts of his French hosts. However, if Rivers could strategically use the Parisian institutions and media as a springboard to accelerate his own career in New York, the French artistic scene symmetrically instrumentalised the presence of an American in Paris in the hope of reasserting the threatened attractiveness of the French capital. Although it seems that Marci’s televisual ambitions did not materialise – no trace of such a show featuring Rivers can be found in the archives – Rivers’s French lessons remain a symbol of this mutual strategy.

Changing style

If Rivers was to make a breakthrough on the Parisian scene, he had to evolve towards a cutting-edge artistic style. Both his American and European dealers were very keen on pushing him in this direction, away from the retrospective exhibitions he had initially conceived. While Rivers had sent to Paris some paintings representative of his career, Marci urged him that the most aggressive worked better: ‘Jean [Larcade, head of Galerie Rive Droite] flipped over the “civil war veterans”. I am so glad that you sent it to us, as it changed his whole outlook about your painting. He loves it when colours are acid and when you let yourself free to do exactly as you feel’.20

From New York John Myers was even more insistent. In a letter from December 1961, when Rivers was already settled in Paris, he lamented the critical success but commercial failure of the artist’s show at Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Such lack of sales made Rivers’s transatlantic triumph even more necessary. Myers wrote:

Also this takes me to my next point of worry. Larry do you think it wise to make your debut in England with a retrospective? Have you thought about this clearly? The image you have created for yourself (in England) is one of radicalism, of satire, humor, etc etc (as reported in the press and from your lecture). Your older pictures are quite different from this … The advanced artists and critics may well attack the show as old hat or god knows what. Also you are too too young for a retrospective … Try to remember that you have now a new public quite separate and different from your old following. I’m not sure you need or want that old public – either in America or Europe.21

It is therefore bearing in mind the admonitions of his dealers to turn toward an art ‘of radicalism, of satire, humor’, with ‘acid’ tones and freedom, that Rivers started to paint a brand new series of works for his Paris and London exhibitions.

Fig.2

Larry Rivers

Double Portrait of Berdie 1955

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Fig.3

Larry Rivers

Drugstore 1959

Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Fig.4

Larry Rivers

French Money II 1962

Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

© The estate of Larry Rivers

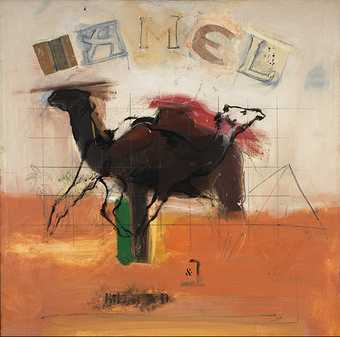

Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson is a result of this new strategy. Working with unusual, sometimes shocking female portraits and nudes was not new to Rivers. In 1955 he had already become infamous for his crude depiction of his aging mother-in-law in Double Portrait of Berdie (fig.2). He had also been using stencilled letters superimposed on his paintings since the end of the 1950s, for instance in Drugstore 1959 (fig.3). In his new Parisian paintings, however, Rivers employed these elements in a brand new way. He combined them with direct references to already existent images: a diagram from a drawing manual in Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson; a banknote in French Money II 1962 (fig.4); a cigarette packet in Amel-Camel 1962 (fig.5). This reinforced the perception of the paintings as concrete images, rather than illusionistic spaces of representation, creating ‘new “factual” type pictures’, as John Myers called them.22

Fig.5

Larry Rivers

Amel-Camel 1962

Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown

© The estate of Larry Rivers

The banality of these images, together with the profanation evident in the appropriation of official banknotes (bearing the portrait of the national hero Napoleon) or the reduction of painting to a pathetic diagram, also produced a spirit of impertinence and dark humour that became the trademark of Rivers’s new style. This effect was enhanced by the colours – mustard yellow, olive green, orange – and by the simplified, directly signifying shapes, contrasting with the expressive brushstrokes.

Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson was first shown in early January 1962 during a group show at Galerie Rive Droite, and immediately struck the critics and was reproduced in the press.23 The test proving conclusive, Rivers decided to move forward in this direction. ‘I have already cancelled what you termed “a retrospective show” with Gimpel’, Rivers wrote to John Myers at the end of January 1962, ‘and we are going ahead with just new works’.24 The French Money paintings and Camel works were completed in the next months, and constituted, together with the Vocabulary Lesson paintings, the core of Rivers’s solo shows, first at Galerie Rive Droite in Paris (from 10 April to 7 May 1962) and then at Gimpel Fils in London (in May 1962).

‘Do not get involved emotionally’: Rivers and the Parisian scene

In Rivers’s first Parisian group show, held in January 1962, Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson was exhibited next to works by ‘some of Paris’s most rambunctious artists’, as one critic phrased it: ‘Yves Klein, St Phalle, Tinguely, Arman and Appel’.25 The same painting was shown again at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in spring 1962 for the exhibition Antagonismes 2, which was, significantly, devoted to the theme ‘the object’.26 In his review Pierre Restany compared Rivers’s contribution to that of his champions, the nouveaux réalistes Arman, Tinguely, César and Klein. Suggesting that the American did not push far enough the direct appropriation of objects in art, he concluded that Rivers’s work was ‘a success in its genre, that is, painting’.27

It seems that most commentators, then and after, insisted on distinguishing between, rather than associating, Rivers’s and his French counterparts’ works. Pierre Schneider, reporting on Rivers’s solo show at Galerie Rive Droite for Art News in 1962, even made it a point that the painter’s new works had nothing to do with their being created in Paris:

Take Larry Rivers, who exhibits his Parisian work at Galerie Rive Droite … The only local influence discernible is that a nude will be overprinted with such indications as ‘vagin’ or ‘poils pubiques’ rather than ‘navel’ or ‘chin’, that a 100-new-franc note rather than a ten-dollar bill will serve as the theme for the artist’s variations, that a package of Gitanes is likely to sit for its portrait rather than one of Camel.28

If one were to believe Schneider, Rivers respected by the letter Marci’s advice to ‘not get involved emotionally with too many things or people and stick to painting’ – as if painting could be so easily extracted from its immediate environment.

In fact, this argument should be understood in the context of the growing competition between Paris and New York in the promotion of the artists then still labelled – with little differentiation – ‘neo-dada’, ‘new realists’ or ‘pop’. A series of comparative exhibitions – from Restany’s Nouveau Réalisme à Paris et à New York (Galerie Rive Droite, July 1961) and William Seitz’s The Art of Assemblage (Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 1961) to The New Realists show at Sidney Janis (New York, October 1962) – aimed at confronting artists, but also at asserting the supremacy of one national production over the other in the new art historical turn that was being negotiated. This competition reached an acme when Robert Rauschenberg famously won the Grand Prize at the 1964 Venice Biennale.29 In this context, commentators were tempted to undermine the true connections, friendships and mutual influences that then existed between some American and European artists, and that should now be recovered, as the art historian Amy Jo Dempsey has argued.30

Niki de Saint Phalle was the first artist of the Parisian circle of nouveaux réalistes that Larry Rivers came to know, in the mid-1950s.31 Born in France but raised in New York, she married very young to the American poet Harry Mathews, who introduced her to the New York avant-garde literary milieu of Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, James Schuyler and Kenneth Koch, who were also close friends of Rivers.32 When Saint Phalle separated from Mathews and settled in Paris with Jean Tinguely at the turn of the 1960s, she was instrumental in building connections with American artists. An undated photograph from the mid-1960s shows Larry and Clarice Rivers together with Niki de Saint Phalle, Jean Tinguely and Frank O’Hara, before the latter’s tragic death in 1966 (fig.6).

Fig.6

Photograph showing (from left) Frank O’Hara, Larry and Clarice Rivers, Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, mid-1960s

Unidentified photographer

Larry Rivers Papers, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University

Courtesy the Larry Rivers Foundation

When Rivers arrived in Paris in the autumn of 1961, he moved in next door to Saint Phalle and Tinguely’s shared studio, Impasse Ronsin, in a neighbourhood (now destroyed) that was then an artists’ colony, where Brancusi famously had his studio.33 Rivers was instantly taken by Tinguely who was working in the cold of Impasse, building odd objects and animated sculptures from metal pieces, rubber and other kinds of junk. He recalled in a 1977 interview: ‘We were in permanent relationship, because Niki de Saint-Phalle, with whom he lived, and himself were out a lot for various events; and also because they spent their time bombarding the wall of their studio, neighbouring mine, and shooting with a rifle’.34

In Paris Rivers could also count on the support of one of the most successful young nouveaux réalistes: Yves Klein himself. The two had met a few months earlier in New York, upon demand of the dealer Georges Marci. In a letter dated March 1961, the latter wrote:

Larry, darling, please do me a big favour. Yves is arriving on the United States S/S on the 27th of March. Could you be down to meet him? … I just do not want him to be depressed in the brave New World. You can be sure that when you come to Europe he will more than reciprocate as he knows everybody and could help me a lot with museums when I am ready to launch you in museum shows.35

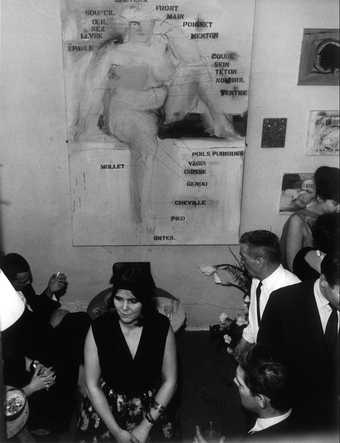

Although Klein’s exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery in New York was rather poorly received, and his overall experience in the United States proved disappointing, his friendship with Rivers remained. ‘I hope you will come as soon as possible’, Klein wrote in July 1961. ‘I will try to return to you as much as I can, your marvelous hospitality’.36 Indeed, Klein spared no effort in ensuring that Rivers would feel welcome in Paris: he introduced him to his artistic circle (Arman, Martial Raysse and Gérard Deschamps, among others) and spoke in his favour to his dealer Jean Larcade, winning from Rivers the nickname of ‘Yves l’incroyable’ (‘Yves the Incredible’).37 ‘Yves has proved to be as true as anyone I’ve known’, Rivers wrote shortly after his arrival in Paris in 1961. ‘We see each other almost 4 or 5 times a week’.38 When Yves Klein and his partner Rotraut Uecker got married in January 1962, they were invited to organise their wedding cocktail party in Rivers’s Parisian studio, Impasse Ronsin. A photograph of the event shows the well-attended party, with, hung in evidence on one of the walls, Rivers’s Parts of the Body: French Vocabulary Lesson (fig.7).

Fig.7

Yves and Rotraut Klein’s wedding cocktail party in Larry Rivers’s studio, Paris, 21 January 1962

Unidentified photographer

Yves Klein Archives, Paris

Mutual impact

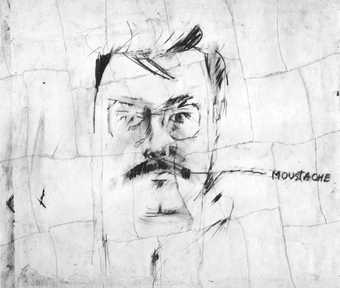

Several works of art attest to the privileged relationship between Rivers and some of the nouveaux réalistes. Rivers collaborated with Tinguely for Turning Friendship of America and France 1962 (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid), a painting-sculpture depicting French and American cigarette packets, equipped with a rotary base. He also worked with Niki de Saint Phalle on several occasions, both in Paris and a few years later, for Tinguely Storm Window Portrait 1965 (private collection). He made a number of individual portraits: of Klein, Arman, and Restany, whose labelled ‘Moustache’ recalls Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson (fig.8).

Fig.8

Larry Rivers

Moustache, Portrait of Pierre Restany 1962

Collection of Dr A. Weseley

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Reproduced in Larry Rivers and Carol Brightman, Drawings and Digressions, New York 1979, p.161

Rivers was always very transparent about the lasting impact of his interchanges with the nouveaux réalistes, both personally and professionally. After Klein’s abrupt death in June 1962, Rivers maintained an enduring friendship with Saint Phalle and Tinguely, who influenced his increasing recourse to the use of objects and mobile devices in his paintings. Since his stay in France, Rivers acknowledged in 1977, ‘there has been many things in my surroundings and in my work that come from that disrespect that Tinguely had towards things and objects’.39

Beyond all doubt, this impact was mutual. A full-length portrait of a pregnant Clarice Rivers that Saint Phalle made in collaboration with Larry Rivers in 1964 (see Saint Phalle and Rivers, Portrait de Clarice Rivers enceinte 1964, collection of David and Isabelle Levy, Brussels) was one point of departure for her future Nanas, which she began to make that same year.40 But the impact reached further than the nouveaux réalistes’ circle. Recalling Rivers’s 1962 exhibition at Galerie Rive Droite ten years later, the influential French art critic Gérald Gassiot-Talabot named it ‘one of the most remarkable of the early 1960s’ considering the ‘trouble’ it caused and its ‘influence’ on the younger generation.41 He probably had in mind the debate that Rivers’s show aroused in the French review Arts in May 1962. Initiated by the critics Raymond Charmet and Michel Ragon, the discussion suggested that Rivers’s art opened a ‘third way’ for painting, between the dominating abstraction and traditional figuration. ‘The movement of an “other figuration” is now launched. A growing number of young artists could be united under this qualification’, Ragon wrote.42 Soon after this Gassiot-Talabot, also a contributor to Arts, created the label ‘figuration narrative’, to gather and display the works of artists working with ‘nouvelle figuration’, such as Hervé Télémaque, Eduardo Arroyo and Gérard Fromanger.43 In reaction to both nouveau réalisme and pop art, which were considered complicit in the perpetuation of a capitalist consumer society, they were hoping to reinject oppositional politics into figurative painting, using the formal means of comic strips, advertisements or ready-made objects. Peter Saul, an American artist also living in Europe at this time, between Paris and Rome, was similarly influential in this regard. However, unlike Rivers he admitted he ‘didn’t meet anybody of any artistic importance’ in Paris, except a few American painters.44

Thus if Rivers was turned away from pure painting towards the use of objects during his stay in Paris, in turn he offered French artists a way to engage with painting again, after the dead-end of abstraction. As he wrote to John Myer shortly after his arrival in Paris, ‘I really feel as if I’ve personally saved painting from a death come of neglect’.45

When Rivers came back to the United States after his European trip, he found that his market strategy had proved effective – in fact, far more so than his American dealers would have it: after an important solo exhibition in New York in December 1962, when he showed his new Parisian works to great acclaim, Rivers left the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, which had supported him for twelve years, to join the prestigious and multinational Marlborough Gallery.46 John Myers resented bitterly what he considered a betrayal: ‘I deeply regret that “international fame” moved you so very far away from us’, he wrote.47 Rivers was now one of the most famous ‘blue chip’ painters of New York.48 Paris may well have seemed remote and provincial at this point. ‘I know you consider Paris the minor leagues, and you are doubtless right’, John Ashbery wrote to Rivers from France after his departure.49

But his productive and rewarding time in Paris never completely left his mind. In his nostalgic Golden Oldies 60s from the late 1970s (fig.9), Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson appears in evidence in the upper-right corner, next to the Camels and the French Money paintings, like snapshots of better years.

Fig.9

Larry Rivers

Golden Oldies 60s 1978

Private collection

© The estate of Larry Rivers