American histories of American art often omit Bernard Perlin, or relegate him to a mere footnote as a keeper of the flame of figuration in an era of abstraction. That history, and Perlin’s place in it, looks rather different, however, when viewed through European eyes. Due in no small part to Orthodox Boys 1948 (Tate N05956), and the circumstances which surrounded its acquisition and exhibition history, Perlin has occupied a much more prominent place in the history of American art as narrated on the other side of the Atlantic. Indeed, it seems no coincidence that the current project – the first collaborative scholarly treatment of Perlin’s work – was commissioned by a British institution. Using this geographic distance as an interpretive lever, this essay will investigate the acquisition, exhibition and reception of Orthodox Boys in order to prise open new possibilities for assessing Perlin’s work and its place in the history of American art.

Orthodox Boys was first exhibited in 1948, the same year it was painted. It was shown at M. Knoedler & Co. in midtown Manhattan as part of the artist’s first solo exhibition, The Work of Bernard Perlin. Even before the paint had dried, Orthodox Boys had the fingerprints of one man, Lincoln Kirstein, all over it. Not only did Perlin carve Kirstein’s initials, ‘L.K.’, into the composition itself, it was Kirstein – a titanic figure in the city’s cultural scene – who planned its unveiling. By Perlin’s estimation, ‘Kirstein was probably the single most influential person in my career’.1 The two met before the war, but lost touch while Perlin served as a war artist and Kirstein joined the so-called ‘Monuments Men’, tracking and liberating masterpieces stolen by the Nazis. Their paths crossed again after the war, Perlin recalls, and soon Kirstein ‘stage-managed my first one-man show at M. Knoedler, the brown velvet Old Master gallery. Lincoln used his considerable clout to bring the gallery into the present with “his” kind of painters.’2 Not only did Kirstein instigate the exhibition, he also proved its most important patron, purchasing The Lovers 1946 – which was later donated to the Museum of Modern Art, New York – as well as Orthodox Boys (Kirstein’s name and address are still written on the back).3

Not everyone was as enthusiastic about Perlin’s painting as Kirstein. Writing for the New York Times, the art critic Sam Hunter sniped:

A demonstration of an unhappy application of ‘influence’ seems to me to be evident … a first showing of paintings of decided technical brilliance, and yet seemingly impoverished and enslaved by the artist’s admirations. I feel that Ben Shahn’s work has provided too much of guiding impulse … the urban megalith is imposing in its ghostly, mournful sobriety and the gamins of the street have a befitting wistful melancholy. But it soon becomes sadly apparent that true authority is lacking. We look in vain for something like Shahn’s grave moral sense, his quick camera-eye sense of visual irony, his hard strength of design. Little seems to have been added; much, subtracted.4

The New Yorker offered a muted but similar critique: ‘Paintings and drawings of great precision and delicacy, whose locale and mood may make you think rather sharply of the work of Ben Shahn.’5 While initially disappointed by these reviews, in time Perlin came to agree, feeling that only his drawings managed to escape the pervasive influence of his mentor. In the late 1950s he wrote laconically of the 1948 exhibition: ‘All paintings with over or undertones of Shahn. All drawings just Perlin.’6 Only in 1949, after painting The Garden 1948–9 (Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton) in Italy, did Perlin feel he had finally produced a ‘Bill of Divorcement against Ben’.7

While Perlin remained in Italy – his painting becoming steadily looser, brighter and more romantic – Orthodox Boys continued to serve as his ambassador back home in America. In the autumn of 1949 it was shown at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh in the annual exhibition Painting in the United States. A label still affixed to the back of the work reads ‘Life Magazine, Metropolitan Museum of Art’. In the spring of 1950 Life sponsored an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum entitled Artists under 35 Years of Age and ran a prominent feature on ‘19 Young Americans’,8 placing Perlin in the company of rising abstractionists including Theodoros Stamos and Hedda Sterne. ‘I was one of the Chosen Few’,9 recalled Perlin, a sentiment that would become rarer for him in years to come as he felt increasingly out of the mainstream.

On 15 January 1951 Life published its iconic photograph of ‘The Irascibles’, in which Stamos and Sterne joined the ranks of painters including Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Willem de Kooning, Adolph Gottlieb, Ad Reinhardt, Clyfford Still and Robert Motherwell (fig.1). From this point onwards the abstract expressionists, as they were beginning to be known, would become the face of avant-garde art in America. An artistic hierarchy was quickly solidifying while Perlin was away in Italy, and by the time he returned to New York in 1954 he mostly found himself on the outside looking in. Viewed from this vantage point, the early reception of Orthodox Boys opens a rewarding window upon a period of fruitful flux in American art; a time, in art historian Alex Taylor’s words, ‘when painting in New York was nothing quite so simple as New York School painting … [and] it wasn’t yet clear who would be the orthodox boys of American painting’.10

Kirstein, symbolic realism and the Tate acquisition

Fig.1

Nina Leen

The Irascibles 1950, photograph published in Life magazine, 15 January 1951

© Nina Leen and Life magazine

In the spring of 1950 Kirstein – ever confident in the supremacy of his aesthetic tastes – charged ahead with an exhibition at the Edwin Hewitt Gallery in New York, which he christened Symbolic Realism.11 The exhibition was meant to stake out critical territory for ‘his’ artists, including Paul Cadmus, Jared French, George Tooker and Perlin. Like a game of street ball, the city’s chief critics were each busy picking their favourite artists, and Kirstein was determined that his ‘team’ trump Clement Greenberg and his growing cadre of abstractionists.12

Belonging to Kirstein’s cabal guaranteed Perlin a certain visibility. Unfortunately, it also yoked him to a volatile – if charismatic – presence, whose tastes and pronouncements in the realm of visual art did not possess the same authority as they did in other fields. Kirstein enjoyed his greatest triumph in the world of dance, bringing the legendary choreographer George Balanchine to New York, where together they built ballet in America from the ground up. Next to ballet, art was a secondary passion for Kirstein, and his adoration of the human figure – especially lithe young men – often meant a rather singular vision with limited applicability to wider audiences. Closely tied to Kirstein, it was not hard for art critics to tar Perlin with the same brush, perceiving him as a gifted but frivolous celebrant of physical beauty. For one prominent reviewer, The Garden 1948–9 (fig.2) – a complex work, as Robert Cozzolino has demonstrated13 – became emblematic of symbolic realism’s shortcomings, both as an exhibition and as a movement. In the words of critic Belle Krasne in her 1950 review of Symbolic Realism, ‘artists who know how to put things nicely can almost get away with saying nothing’.14

Fig.2

Bernard Perlin

The Garden 1948–9

Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton

© Bernard Perlin

While the exhibition met with mixed results in New York, when Kirstein brought the show to London a few months later as Symbolic Realism in American Painting 1940–1950 it received wide acclaim. Unlike New York, where Kirstein’s crew had to battle for attention against the newly ascendant abstract expressionists, in London, at the recently founded Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), Kirstein could present the symbolic realists as the uncontested vanguard of American art. Moreover, by timing the exhibition to coincide with a London tour by the New York City Ballet, which he had co-founded, Kirstein was able to conjure – at least for British audiences – the notion of one great American gesamtkunstwerk, made in his own image.

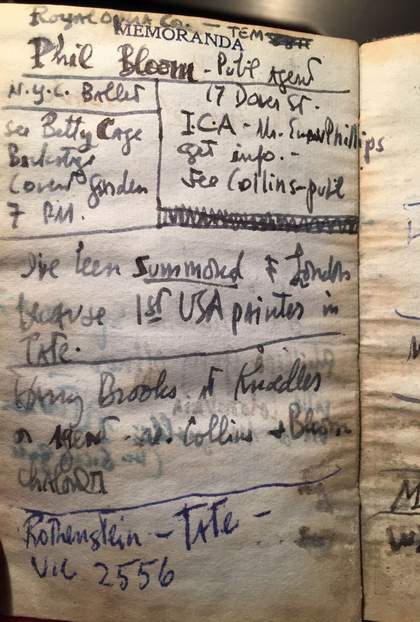

If Perlin’s close association with Kirstein constituted a mixed blessing in New York, in London it proved a boon, providing a readymade network of critics, curators and buyers. For the London exhibition, Kirstein swapped The Garden for Orthodox Boys, which became one of the stars of the show. While in London, Kirstein donated the work to the Tate Gallery through the ICA. Perlin was thrilled. He came from Rome to see the show along with his lover, the Polish émigré writer Konstanty Jeleński.15 In his datebook he jubilantly recorded a series of glittering engagements (fig.3): seeing the New York City Ballet; attending the Royal Opera; visiting the ICA; and meeting Sir John Rothenstein, the director of Tate. To himself he proudly noted, ‘I’ve been summoned to London because 1st USA painter in Tate’.16 A couple of years later, in a handwritten note to Tate curator Ronald Alley, Perlin wrote that having Orthodox Boys in the museum collection ‘honors me enormously, I assure you’.17

Fig.3

Bernard Perlin

Page from datebook, 1950

Collection of Michael Schreiber

At first, without contemporary American paintings in the collection for context, and with seemingly limited knowledge of Jewish life and customs, Tate staff seemed puzzled about what to make of Orthodox Boys. From 1952 onwards Tate curators wrote a series of letters to Perlin asking for more information about the scene, which the artist answered dutifully and with slight bemusement.18 Internal documents reveal a genuine, although rather naïve, attempt by gallery staff to link Perlin to English precedents. In 1950 Tate’s deputy keeper wrote that Perlin ‘Has painted many pictures of N.Y. city life in mediaeval miniature style’, adding that he detected ‘Resemblance to pre-Raphaelite painters’.19 In America, the ubiquity of Ben Shahn had made Perlin seem comprehensible but derivative to early viewers. In England, Perlin had the opposite problem: it was easier to appreciate his originality but harder to understand him.

Even if Tate was not entirely sure what it had acquired, it was nonetheless proud of the acquisition. Orthodox Boys became a symbol of Tate’s increasingly international scope, and its desire to tell the unfolding story of modern art not only within Europe but in the wider Western world. In a museum guide from 1952, under ‘Modern Foreign Painting’, the gallery listed Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Edward Munch, Marc Chagall, Wassily Kandinsky, Giorgio de Chirico and other modern masters before coming to ‘the American, Bernard Perlin’.20 Briefly, at least in England, Perlin stood proudly atop Parnassus as the preeminent representative of American modernism.

Orthodox Boys would be put on display frequently at Tate over the decade following its acquisition. By the mid-1950s, however, British appetites and tastes were beginning to shift. In 1956 the blockbuster exhibition Modern Art in the United States opened at Tate, showcasing numerous works from the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The exhibition proved a watershed for British viewers, many of whom were unacquainted with the works of Pollock, Rothko and other abstract expressionists. The exhibition also included a number of figurative paintings, although none by Perlin. While realistic works still proved popular with audiences, especially Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World 1948 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), critical favour increasingly turned toward abstraction. Before long, art critic David Sylvester could liken changing British attitudes toward American art, especially abstract expressionism, to a religious conversion ‘by an advance guard of pioneering freelance missionaries’.21 Those ‘seriously concerned with contemporary art’, he went on to explain, ‘take it for granted that America is now the main creative centre … and the non-specialists are just about beginning to get used to the idea, though without being terribly keen on it’.22

Abstraction’s dominance

In the late 1950s Perlin enjoyed a final flurry of recognition before the art world – and especially the art market – began to turn away from him. In 1956 he was chosen alongside Mark Tobey to represent the United States at the twenty-eighth Venice Biennale. Upon request, Tate shipped Orthodox Boys to Italy, and indeed the painting still bears an Italian customs stamp on its reverse. Several months later, the painting travelled to the Art Institute of Chicago to form part of the 1957 group exhibition American Artists Paint the City.

Fig.4

Bernard Perlin

The Farewell 1952

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

© Bernard Perlin

In 1957 Perlin’s work appeared in the annual exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and in 1958 he was one of seventeen artists featured in the American pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair. In Belgium, one of his works caught the eye of the former First Lady of the United States, Eleanor Roosevelt, who wrote, ‘Even I – no expert in modern art and in need of far more education and application in looking – came away feeling that I could live very happily with a painting … by Bernard Perlin called The Farewell [fig.4].’23 Such praise unintentionally damned Perlin and like-minded peers as much as any criticism, bolstering the narrative that figurative painting was less challenging than abstract art.

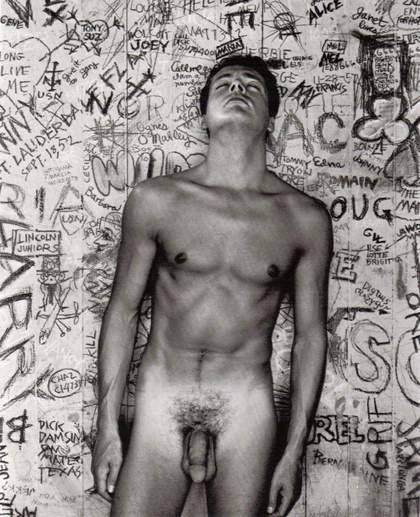

When Perlin returned to America from Europe in 1954 he could already see the writing on the wall. On the one hand, he still had the support of close friends, such as the photographer George Platt Lynes. Fondly remembering Orthodox Boys, Lynes invited Perlin to festoon one of his studio walls with graffiti for a photo shoot (fig.5). Later that year, he used the image for a holiday card, which also served to advertise Perlin’s return to New York City. Beyond his regular coterie, however, Perlin’s reception was not as enthusiastic, and he watched with growing frustration as ‘the fashionable abstract expressionism of the bucket brigade’ became the talk of the town.24 ‘It would be very pleasant and very easy to become a nonobjective painter. Too easy’, a peeved Perlin told the writer Selden Rodman in 1956. ‘I am sure I will go on, however gropingly, as now, toward humanity and the mirror of where we are, and who I am, and what truth is.’25

Fig.5

George Platt Lynes with graffiti by Bernard Perlin

Graffiti Wall 1954

Collection of Michael Schreiber

Beneath his disdain, however, Perlin shared more than one might expect with the city’s non-objective painters. In rejecting abstraction he utilised the same language of existential struggle that its practitioners used to justify it. The same year, in fact, Rothko had his own heated discussion with Rodman. Attempting to pay the artist a compliment, Rodman remarked that he considered Rothko ‘a master of color harmonies’.26 Taking umbrage, Rothko barked back: ‘The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point!’27 Shaped by a similar mid-century intellectual milieu – inflected by a common Jewish identity – Perlin had more in common with Rothko, and indeed other abstract expressionists, than he often cared to admit.

Not only did the artistic fusillade of the 1940s and 1950s obscure conceptual common ground between figurative and abstract artists of the period, it also camouflaged aesthetic parallels. As Cozzolino argues, ‘Looking closely at realist paintings between 1947 and 1960 reveals just how much Kirstein’s group adopted from abstract painting’s new configuration of space, depth, pattern, and the relationship between surface and meaning.’28 Perlin’s Orthodox Boys provides a case in point. While Kirstein read it as a pledge of allegiance to his school of symbolic realism, its intricate web of graffiti enters into dialogue with Mark Tobey’s ‘white writing’ and Adolph Gottlieb’s ‘pictograph’ paintings of the late 1940s. Looking ahead, it also anticipates the grim calligraphy of Morris Louis’s Charred Journal series of 1951 (various collections), which evokes the trauma of the Shoah.29

Even as Perlin’s distaste for abstraction grew more pronounced in the 1950s, he continued to absorb lessons from it, whether he confessed it or not. In the mid-1950s he took up oil painting, the preferred medium of the abstract expressionists. This change of medium may in fact have cost him Kirstein’s patronage, Perlin speculated, since around this time his former champion abruptly stopped speaking to him.30 At the same time, Perlin recounted, his brushwork became looser and his compositions became ‘less specifically story-telling, less specific in content’.31 Furthermore, despite vociferously disavowing the automatic, experimental processes of abstract contemporaries, he began to integrate some of these very elements into his creative process. Instead of imposing his figures upon their backgrounds, Perlin started to stir the surfaces of his canvases until he found the figures within them, letting blotches, smudges and other painterly incidents determine the forms that emerged.32 Although he did not quite see it as such at the time, Perlin was painting his way towards a productive middle ground, neither resolutely figurative nor abstract.

Fig.6

Bernard Perlin’s home, Ridgefield, Connecticut

Photo © Aaron Rosen 2015

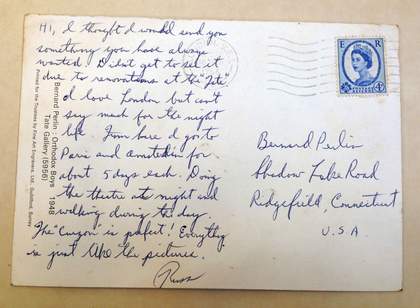

Fig.7

Postcard sent to Perlin from Tate with Perlin’s Orthodox Boys 1948 on the front, 1966

Bernard Perlin Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven

Unfortunately for Perlin, it was not an era congenial to compromise. Aside from a few perceptive voices, like that of his old friend Glenway Wescott,33 the nuances and ambiguities of Perlin’s ever-developing practice were mainly lost on critics. ‘This grand-name-self-consciousness and dedication-to-one’s-style-because-it’s-one’s-style can be suicidal to art’,34 Perlin warned, predicting the fatigue that would eventually doom abstract expressionism. Eventually, he grew tired of waiting for this prophecy to come to pass, and in 1959 he decamped for rural Connecticut. Leaving his cosmopolitan life behind, he built himself a home and studio from a derelict goat shed using material from collapsed barns (fig.6). In 1965, by then firmly settled into his new life, Perlin admitted to a local reporter that ‘It’s lonely not to be in vogue’.35 Yet he remained proud that he had not compromised his vision, adding ‘I’m very happy. I have supported myself for 25 years painting what I really want to paint’.36

London, and the success it represented for Perlin when he saw Orthodox Boys on display in the summer of 1950, could hardly have seemed further away from Ridgefield, Connecticut. In 1966 a friend passing through London mailed Perlin a postcard of Orthodox Boys from the Tate Gallery gift shop, noting poignantly that it was ‘something you have always wanted’ (fig.7). Perlin saved the card for nearly fifty years, until his death in 2014. Long after his star had faded in the American art world, Perlin looked to London as a place where he had truly made his mark.

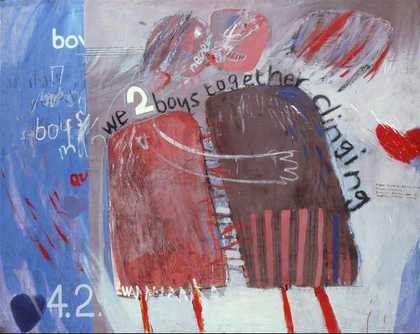

Fig.8

David Hockney

We Two Boys Together Clinging 1961

Arts Council Collection, London

© David Hockney

Photo © John Webb

Indeed, while Perlin begat no immediate followers in America, his painting of two fearful Jewish boys has had an unexpected influence in Britain. In We Two Boys Together Clinging 1961 (fig.8), which takes its title from a homoerotic poem by Walt Whitman, David Hockney recreates graffiti scrawled in a bathroom stall. Despite their differences in style, the two works share a similar structure and subject, and it is tempting to imagine that Hockney recognised and amplified the gay subtext in Perlin’s Orthodox Boys. For his part, the artist Peter Blake has reverently mentioned Orthodox Boys on multiple occasions, recalling:

I saw it often, and as a young artist I was very influenced by it … I was intrigued by these two serious little boys holding what I guessed to be their homework, and by the extraordinary wall of graffiti, which I spent hours reading and deciphering. The painting hinted at a city (New York) which I was only beginning to learn about, the writers and actors, be-boppers, boxers and wrestlers, and of course the painters.37

In mid-century New York, Perlin was merely one among many artists competing to define the city and its art. In London, however, Perlin’s metropolis – gritty, dangerous, yet crammed with possibilities – could represent the New York. And Perlin, at least for one aspiring English painter, could be its greatest artist.