Rabih Mroué’s On Three Posters (Tate T13196) is a seventeen-minute, single-channel colour video with sound, described by the artist as a ‘video testimonial’.1 The work can be displayed as a projection or on a monitor within gallery spaces. The artist has specified that if it is played on a loop, audiences must have the option to restart the video at any moment so they can view it from the start, and that headphones and seats must be provided if the video is screened on a monitor or near other works with sound.

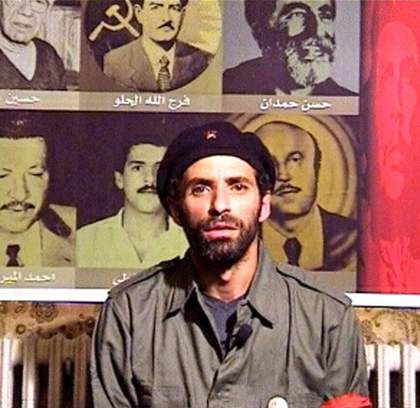

Fig.1

Rabih Mroué

On Three Posters 2004, as installed at BAK (Basis voor Actuele Kunst), Utrecht, 2010

Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut/Hamburg

Photo: Victor Nieuwenhuijs

The video begins with a close-up of the artist seated against a white background (fig.1). He addresses viewers directly: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, good evening. I’m happy to be with you here in this room and I would like to thank you for attending this session’. Mroué explains that this video is a critical commentary of a stage performance called Three Posters, directed by himself and Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury, first performed at the Ayloul Festival inBeirut in 2000. The artist’s address recalls the live nature of theatre while reminding viewers that they are not in fact witnessing a performance. Mroué’s use of the word ‘session’ invites viewers to think of the video as a type of lecture or seminar in which they will be asked to think about the artistic and political questions raised by the stage performance.

Following the introduction, the video has six sections. Each opens with a white title on a black screen and combines scenes with the artist seated in front of a white background with footage from Three Posters as well as other television and video recordings. The artist’s monologue continues to be heard over the footage and other recordings, which do not have sound of their own.

In the first two sections, ‘The Tape’ and ‘The Genesis’, Mroué recalls how he first discovered Jamal al-Sati’s video, made in advance of his suicide mission in 1985, and describes his surprise at hearing al-Sati perform his speech three times before deciding on the single version to be aired on Lebanese television. Mroué explains that at that moment he and Khoury recognised that the martyr was not a hero but a human being and that this realisation prompted a series of aesthetic-moral dilemmas for them, each of which are posed in the video as questions that appear on the screen:

Should we allow a public ‘foreign to the party and to the family’ to witness a martyr’s emotions before his death?

Could we present a tape that did not belong to us?

Would he have wanted this video to be seen with all its rehearsals?

Were we exploiting this tape to make an ‘art-work’ from which we would draw both moral and financial profit?

Were we, in a sense, violating the sacred space of the martyr?

These questions remind viewers that On Three Posters introduces a secondary layer of critical commentary around the original performance. They also introduce philosophical dilemmas about the martyrdom, the authorship of a video artefact, and the ways in which electronic media (video and television) influence and act upon their audiences. If we are accustomed to thinking of video as the recording of something that has already happened, the artist asks, how might we understand a martyr testimony as a video of its speaker’s suicide mission, which is going to happen but which has not yet taken place? Mroué explains in the video that he and Khoury felt that al-Sati’s declaration, ‘I am the martyr’, in the present tense, raised a fundamental paradox between the living speaker who utters those words and the speaker’s death implied by the statement. This paradox inspired them to try and analyse such an ambiguous and indeterminate death through three figures: an actor, a resistance fighter, and a politician. The tripartite structure of the original performance was framed by these three figures.

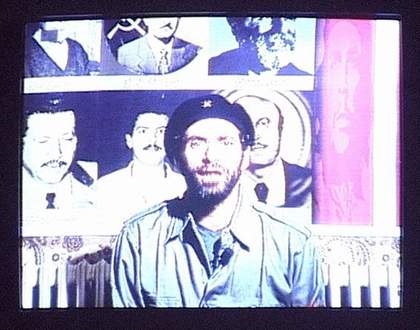

Fig.2

Detail of video still of Rabih Mroué's On Three Posters 2004

Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut

The third section, titled ‘The Actor: The Truth of Fabrication’, addresses Mroué’s role in the 2000 performance, where, posing as a resistance fighter Khaled Rahhal, he delivered a testimony to the audience (fig.2). The purpose of this section in the video is not to set up a theatrical deception which is then unmasked, but to deconstruct the logic behind such a gesture – something that in the original performance was left up to the audiences to deduce on their own.

The fourth section, ‘The Martyr: The Fabrication of Truth’, introduces what the artist designates as the ‘non-space’ of video martyrdom: the duration of time between the conclusion of the testimony (when al-Sati announces his death) and the completion of the suicide mission. This section continues to probe the paradox of a speaker who can announce his own martyrdom while still alive.

The fifth section, ‘The Politician’, explains why the directors included an interview with an actual Lebanese politician in Three Posters and prompts viewers to differentiate between an individual’s decision or desire to carry out a suicide mission in negotiation with a political party, and the wider political forces influencing these operations.

The final section, ‘Travel and Translatability’, describes the reception of the performance Three Posters when it was staged outside of Lebanon. As in the previous sections, the video of Mroué speaking is interspersed with footage from earlier performances, including shots of audience members. Here viewers are asked to think not only about how audiences outside of Lebanon might have understood the history of the ‘civil wars’ – too complex to be summarised in the type of news reports with which they would have been most familiar – as well as how current political events, including the suicide bombings of the Twin Towers in New York in 2001, and the Palestinian Intifada, would have influenced their reception of the performance. The video concludes with the artist’s statement that they could not continue to perform Three Posters, that it had become a ‘zero-sum game’. In the final shot, viewers are left simply with an empty chair set against the white background.

The questions raised by Mroué in this final section are particularly resonant given his upbringing in Lebanon and the point in his career in which this piece was made. Born in Beirut in 1967, the year in which the Six Day War ended with Israel’s resounding defeat of the Arab forces,2 the artist directly witnessed the ensuing political turmoil as Lebanon transformed from being arguably the only surviving liberal democracy in the region to becoming a synonym for destruction through the globally televised images of car-bombings, kidnappings and fierce gun battles that took place during the ‘Lebanese Wars’ between 1975 and 1990.3 These wars, which are often described simplistically as constituting one civil war, were not experienced by the Lebanese people as a single event but rather as a discontinuous series of intermittent and ongoing conflicts of varying intensities, enacted by multiple actors in different regions, involving distinct groups and interests.4

While the outbreak of internecine conflicts in 1975 is seen as signaling the demise of Beirut’s image as a cosmopolitan and touristic capital, Khoury argues that the onset of war had been integral in stimulating artistic experimentation in the city, most particularly in the domain of theatre: ‘The rebellious spirit of modern poetry met with a rebellion in theatre and the emergence of a countercurrent vanguard movement on the eve or and during the civil war with two principal figures, Roger ‘Assaf and Remond Jebara’.5 The war also gave rise to new form of experimental art and literature that replaced allegory and moral symbolism in favour of narrative forms that used idiomatic Arabic and self-consciously focused on the representation of the lived present: ‘The war was the context for the quotidian and it was inconceivable to write about everyday life in abstraction from it’.6 This paradigm shift in Lebanese drama would be integral to Mroué’s exploration of a semi-documentary theatre that troubles the distinction between factual documents (newspaper clippings, sound recordings, photographs and videos) and fictional stories or testimonies.

Mroué graduated from the LebaneseUniversityin 1989, with a degree in acting, and so was heavily influenced both by this emphasis on the everyday and by the renewed interest in experimental theatre. One of his first productions, ‘The Journey of Little Gandhi’, adapted from Khoury’s 1989 novel of the same name, is representative of his artistic interests at this time. In the novel, a namless narrator (a young writer) retells stories related to him by Alice (a former prostitute), especially one about ‘Gandhi’, a shoe shine, who was killed by a stray bullet on the day the Israelis invaded West Beirutin 1982. In the manner of traditional hakawati (storytellers), Alicedigresses to incorporate other stories of her own life and tales told by other characters. Yet it is the narrator who controls and manipulates these other voices by ‘pulling them into his own frame of reference’.7 The result is fragmented narrative that both lacks a fixed center and undermines the search for a final truth. In translating Khoury’s work for the stage Mroué similarly asked, through experiments in theatrical staging, who might speak for whom and what kind of authority might be granted to those speaking positions.8

By 1999, when Mroué began to collaborate with Khoury on Three Posters, both he and the author were established figures in Beirut who had worked with one another several times previously. (As the artist notes in On Three Posters, he was instantly recognised by the audience as a well-known actor when he took the stage.) Moreover, at this point the artist had begun to question his training in traditional forms of theatre; as he discusses in his interview with the author, his 1998 performance of Come in Sir, We Will Wait for You Outside was his first departure from the lessons of theatre that he had been taught at university. Three Posters thus marked a significant maturation of Mroué’s work: it was a performance in which he openly disregarded the standard trappings of theatre, even the experimental theatre that had characterised theBeirut scene since the civil wars, and foregrounded the interest in media that had arisen from his work in television earlier in the decade.

The martyr video

Fig.3 Front page of the Beirut daily newspaper al-Nahar, 7 August 1985, featuring the story about Jamal Al-Sati's 'martyrdom operation'.

In 1999 Mroué came across the video testimony that would serve as the origin for Three Posters (in On Three Posters Mroué explains that al-Sati’s video was discovered ‘neglected, resting on a shelf in the offices belonging to the Lebanese Communist Party’ by a friend of his, who shared the video with him). This was a tape made by Jamal al-Sati, a Lebanese combatant for the leftist National Resistance Front, which, according to the artist, was taped a few hours before al-Sati carried out a ‘martyrdom operation’ against Israeli forces in 1985. On 7 August 1985, one day after the operation was carried out, the Beirut daily newspaper al-Nahar published the following report:

The Resistance has issued a statement saying that ‘the National Lebanese Resistance Party has promised our people from the first day of its launching to continue the fight until the land is completely free, without any conditions from the Israeli conquest and its traitor agents … to achieve this liberation the hero-martyr Jamal al-Sati performed a suicidal attack against one of the enemy’s strongholds, the building of the Military governor in Hasbiyya (Zaghlé centre) before noon on 6 August, where general Fardi, five intelligence officers, more than 15 Israeli soldier guards, 10 soldiers for communication and management, and about 40 soldiers of the agent [Antoine] Lahd [Head of the pro-Israeli South Lebanese Army]. We were unable to destroy this location using regular methods, so the hero-martyr Jamal al-Sati performed this huge operation. Based on our investigations, the location was destroyed by a TNT payload weighing 400kg loaded on a mule, near the wall of the building which was scattered in all directions and killed all who were in it. (fig.3)9

Al-Nahar does not name its sources, so we cannot be sure of the veracity of this information. The report does, however, give the reader a sense of how such operations were represented in the Lebanese media at this time. The above quotation not only provides the supposedly factual details of the operation but also reiterates the ideological messages behind resistance: it proclaims al-Sati as a ‘hero-martyr’, a stock phrase that continues to permeate the language of Lebanese politics to this day.

News of this operation was also delivered in the form of the video-taped testimony made by al-Sati just prior to his death. At that time, video testimonies were customarily recorded a day before martyrs executed their missions. Immediately after the mission was carried out, such tapes would be sent to the government-owned station Télé Liban, which aired them during the evening news broadcast.10 Thus, these video testimonies remain a unique part of the collective memory of the Lebanese people who lived through the wars of 1975–90.

In making the video al-Sati repeated his testimony three times before deciding on a single version to air. The three testimonies are nearly identical, but they are each marked by involuntary hesitations and stumbles that prompted Mroué to devise an artistic scenario ‘to critique the concept of martyrdom and, by extension, the powers that nourish and encourage such ideologies, official or otherwise’.11 Mroué’s collaboration with Khoury, which came out of a longer artistic dialogue between the two, used the video as an opportunity to question how the prevalent images of martyrdom had impacted on Lebanese political subjectivity. Their idea to use the video in a theatrical performance was a means of challenging the self-evident status of the archival document as well as disrupting the conventions of theatre based on character, plot and mise-en-scène. Mroué’s experimentation with the conventions of theatre arose not only out of a desire to question his traditional training in acting but also out of the technical experience he gained working at a major Lebanese television station.

Mroué and Khoury, who worked together on every aspect of the performance from writing to directing (see the interview with the artist), initially planned to present the video as it was, without modification or commentary. However, they realised that this would not in itself be enough to call into question the ideological and technological mechanisms of the martyr video. In other words, the screening of al-Sati’s tape alone would not be enough to provoke audiences into questioning their ingrained assumptions about these videos and their habits of viewing them. Instead, they produced and directed Three Posters, the title of which referred to the three spoken testimonies of al-Sati in the uncut rushes of the video and to the performance’s tripartite structure: three ‘chapters’, each one, as noted before, based around a single figure, an actor, a resistance fighter, and a politician. It also disrupted the singularity conventionally ascribed to the martyr poster as a commemorative image.

The performance

For the first chapter the audience entered a darkened room in which only a television monitor was visible on stage (fig.4). After a few moments Mroué (the actor) appeared on the screen wearing military fatigues, a beret with a five-pointed red star, and a red ribbon on his left arm. Behind him was a collage of portraits of actual leftist martyrs, including one of al-Sati positioned prominently behind his right shoulder (fig.5), and the flag of the Lebanese Communist Party. Looking at the camera, Mroué stoically read a statement:

I am the martyr comrade Khaled Rahhal. I was born in 1964 into a hardworking family that taught me the principles of freedom and justice. I enrolled in the Communist Party in 1982 and joined the heroes of the National Resistance Front, who sacrifice their blood to free our occupied lands in the South and the West Bekaa. My name is Khaled Rahhal, and I am now here to declare my last call before committing, tomorrow morning, a suicide mission on which the Front Command has agreed.12

Fig.4

Installation view of the monitor in Three Posters 2000 showing Rabih Mroué as Khaled Rahhal

Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut

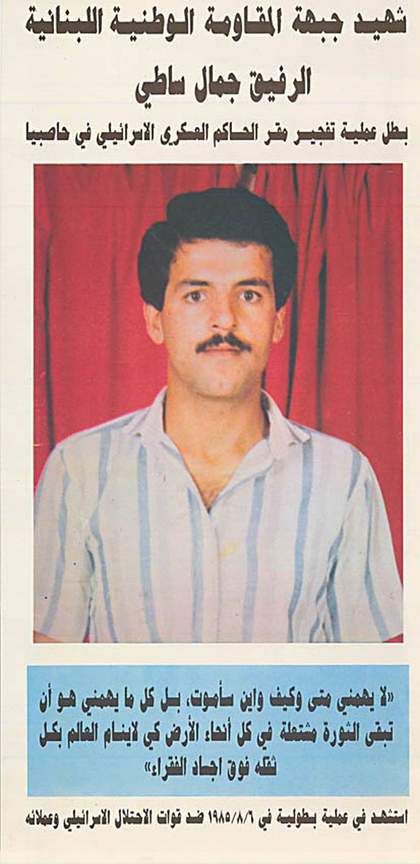

Fig.5

Poster of Jamal al-Sati announcing his martyrdom 1985

Lebanese National Resistance Front, Lebanese Communist Party

Image courtesy of Zeina Massri

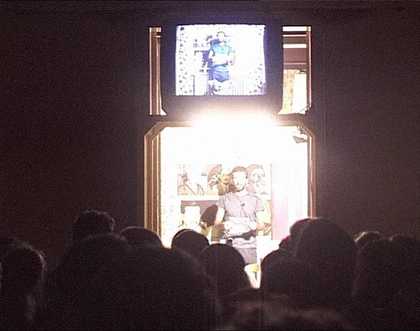

Fig.6

Installation view of Three Posters performed at the Ayloul Festival, Beirut, in September 2000, showing Rabih Mroué as Khaled Rahhal on stage below a monitor screening the live performance.

Courtesy the artist

The posters of actual martyrs pinned to the wall behind Mroué lent authenticity to the artist’s performance to the extent that an unsuspecting audience member might have taken the video to have been a pre-recorded testimony of a genuine martyr. However, as soon as the artist finished three different takes of his statement, he abandoned the role of the actor and spoke as himself, Rabih Mroué, reading out his own name, his date and place of birth, and a (partly fictional) history of his participation in the Lebanese Communist Party. At that moment Khoury came onto the stage and opened a door to reveal Mroué standing in front of a camera (fig.6). The audience then realised that what they had just witnessed on video was not a moment fixed securely in the past but a live performance, one that rendered the line between fiction and reality unstable. ‘At that instant, the fabrication of the false moment was made apparent’, Mroué said.13

Furthermore, by drawing attention to the constructed nature of martyr videos, in particular to their specificity as testimonies recorded prior to an event but only watched after the fact, Mroué and Khoury destablised the sense of time, from the future to the past to the present, and by extension confounded distinctions between ‘as live’ and ‘alive’.

This sense of confusion was then taken forward into the second ‘chapter’ of the performance devoted to the resistance fighter, in which the video of al-Sati rehearsing his testimony was screened on the same television monitor. When seen in relation to Mroué’s fictitious portrayal, it becomes possible to think of al-Sati’s testimony as a highly theatrical performance of martyrdom itself; the repetitions and stutterings seemingly affirm the ‘liveness’ of his recording. Yet in actuality these ‘uncut rushes’, as Mroué has called them, only serve to magnify the spectre of death in al-Sati’s video, a real, irreversible death.

In the third chapter, the videotape is changed and an elected Lebanese politician, Elias Atallah, now appears on the monitor. He is shown in a close-up, but his features are underexposed, preserving his anonymity. The explicit purpose of the third chapter, as artist explains in his interview with the author, was ‘to see what the Communist Party would say about this operation, since we were criticising and questioning how the party authorised these suicide missions’.14

The ‘video testimonial’

Following the directors’ decision to stop performing the work, the project now lives on as the single-channel video, On Three Posters, which the artist filmed using a Beta camera for shooting and a digital software program for editing. The master format was Betacam Tape. The artist currently permits the work to be shown only in the context of a gallery or museum (ideally in a room approximately 5 by 6 metres). Tate acquired the work in 2010 through Mroué’s Beirut- and Berlin-based gallery, Sfeir-Semler, in the media of Digital Beta and DVD.

On Three Posters should not be understood either as a replication of the stage performance, which it clearly is not, or as a substitute for the original performance. Rather, it is best viewed as a supplementary text that introduces a secondary layer of critical reflection on the challenges of appropriating a videotape that was never intended to be shown in public.

This In Focus aims not only to situate the video within its historical context and the Beirut contemporary art scene but also to explicate its inherent correlation of media with death and what this has to say about digital representations of death and martyrdom in the early twenty-first century.