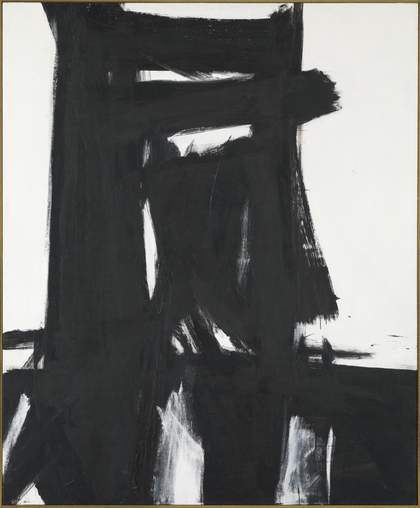

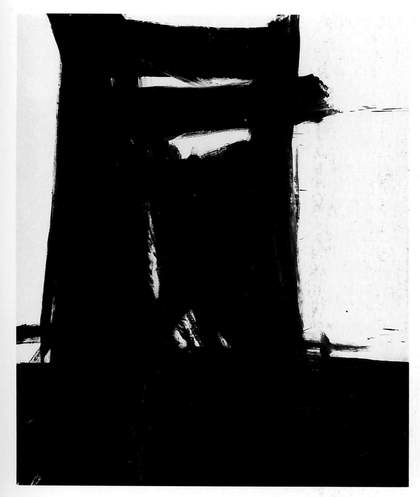

Fig.1

Franz Kline

Meryon 1960–1

Oil on canvas

2359 x 1956 mm

Tate T00926

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2017

The title of Franz Kline’s painting Meryon 1960–1 (Tate T00926; fig.1) is a homophonic pun. It arguably refers both to the nineteenth-century French printmaker Charles Meryon, who was renowned for his moody etchings of medieval Paris, and to the upper-crust town of Merion on the Pennsylvania Main Line, which was only two hours’ drive and yet worlds away from Kline’s humble birthplace of Wilkes-Barre in the Coal Region of north-eastern Pennsylvania. Only those familiar with the modern master of printmaking and with the Pennsylvania town would have understood these titular references, yet to view the painting without them in mind would be to deny Kline’s Meryon its full meaning.

The title’s ambiguity might appear to serve the cause of Kline’s abstraction, but Kline himself did not view his abstraction in such absolute terms. As the artist explained in 1960: ‘I don’t have the feeling that something has to be completely non-associative as far as figure form is concerned.’1 That Kline initially held naming sessions for his paintings with friends, including notably for eight hours with the artists Willem and Elaine de Kooning and art dealer Charles Egan for his first exhibition of 1950, testifies to the fact that Kline took his titles very seriously from the earliest phases of his abstraction.2 As Elaine de Kooning recalled in an interview: ‘We kept on picking names of places that meant something to him.’3 Most of Kline’s titles fall into a few similar categories of reference, as will be shown below, and the fact that Kline asked for his friends’ help in selecting titles does not mean that his own input was any less.

‘How do you want your pictures to be read?’, the British art critic David Sylvester asked Kline in 1960.4 ‘Are they to be read as referring to something outside themselves? Do you mind whether they are? Do you mind whether they’re not?’ Their subsequent discussion on this crucial point deserves to be quoted at length:

Kline: No, I don’t mind whether they are or whether they’re not. No, if someone says, ‘that looks like a bridge’, it doesn’t bother me really. A lot of them do.

Sylvester: And at what point in doing them are you aware that they might look like a bridge?

Kline: Well, I like bridges.

Sylvester: So you might be aware quite early on?

Kline: Yes, but then I – just because things look like bridges, I mean… Naturally, if you title them something associated with that, then when someone looks at it in the literary sense, he says, ‘he’s a bridge painter’, you know.

Sylvester: And do you ever encourage an image along? Consciously? Do you ever nurse it?

Kline: No, no. There are forms that are figurative to me, and if they develop into a figurative image that’s – it’s all right if they do. I don’t have the feeling that something has to be completely non-associative as far as figure form is concerned.

Sylvester: But do you have a feeling that they have to be associative either? I mean the way that de Kooning in his later paintings, you know the paintings, the sort of outdoor paintings in the last two years, wants them, really wants them to correspond to experiences of parkways and… You don’t think in those terms?

Kline: I think that if you use long lines, they become – what could they be? The only thing they could be is either highways or architecture or bridges.5

Given Kline’s extensive knowledge of printmaking and his habit of titling his works after places in Pennsylvania, the viewer of Meryon is prompted to reflect on the significance of these allusions to Meryon and Merion and what may they have in common, in view of the painting itself and the rest of Kline’s oeuvre. The resulting verbal and visual abstraction alludes to and illustrates the modernisation of the built environment that Meryon and Merion – to the audiences who know this name and this place – symbolised in France and the United States. Just as Meryon responded to Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s renovation of Paris from the 1850s onwards, a change to which he was passionately opposed, Merion and the Main Line in general represented the suburbanisation of the United States. Whereas the French, whether sympathetic or not to Haussmannisation, were committed to the city, the Americans, following the English model, embraced the suburb as a bourgeois utopia, as the historian Robert Fishman has argued.6 Meryon can function equally well, albeit differently, with one reference or the other, but most powerfully when we are aware of the implications of both allusions and their combined meaning.

Merion

For most of those in the art world who first encountered Meryon when it was shown at Kline’s exhibition of new paintings at the Sidney Janis Gallery in December of 1961, it would likely have been the connection to Merion, Pennsylvania, that registered first of all, and not only because Kline was in the habit of naming his paintings after places in Pennsylvania. Merion was the home of the Barnes Foundation: a private educational institution, first established by Dr Albert Barnes, which had been turned into a public art museum after the founder’s death, against his express wishes. In 1961, the year that Kline titled Meryon, Barnes’s collection of Picassos, Matisses, Cézannes and Renoirs was valued at $100,000,000, and the museum had only recently opened to the public and, after much public and legal debate, with no admission fee.7 The art world in New York, even if it had not been familiar with the geography of suburban Philadelphia, would have known the name of Merion and many visitors to the exhibition may have already made the short trip to visit the finally publicly accessible collection.

For those outside the art world who recognised neither the esoteric name of the printmaker Meryon nor Merion as the site of America’s most controversial new art museum, Meryon would probably have nevertheless brought to mind Merion, Pennsylvania. A series of books and films released at mid-century had taken as their settings the townships along the Main Line, one of the most elegant of which was Merion.8 These works of fiction, including the film The Young Philadelphians (1959) starring Paul Newman, emphasised the strictures, codes and manners of the wealthy, exclusive upper class society that seemed to belong to another time or place. In them a protagonist, often of working class origins, comes into conflict with this world from another world. This had happened to Barnes, a working-class Philadelphian whose fortune from the discovery of Argyrol, a drug for the treatment of gonorrhoeal infections, had allowed him to build a world-class art collection. Barnes insisted on giving the less fortunate special access to his collection and denying entry to the elitist Philadelphia society that he believed had spurned him and that he so loathed.9

While Meryon cannot be reduced to a simple pictorial site of class conflict, it must be mentioned that Kline’s many other titles referencing trains, railroads and places in Pennsylvania belonged very much to the other side of the tracks: namely, that of working-class coal country, which had been Kline’s birthplace. These include Cardinal 1950 (private collection), Chief 1950 (Museum of Modern Art, New York) and Diamond 1960 (private collection), which were names of trains and locomotives; C&O 1958 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), referring to the Chesapeake and Ohio, and Laureline 1956 (private collection), which were names of railroads in coal country; and many that refer to places in that region, including Thorpe 1954 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), Wanamaker Block 1955 (Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven), Lehigh 1956 (private collection), Luzerne 1956 (private collection), Mahoning 1956 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York), Shenandoah 1956 (private collection), Hazelton 1957 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), Delaware Gap 1958 (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.), Pittston 1958 (private collection), Scranton 1960 (Museum Ludwig, Cologne), Lehigh V Span 1959–60 (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco), Bethlehem 1959–1960 (Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis), Shenandoah Wall 1961 (private collection) and Nesquahoning I 1960–1 (private collection).

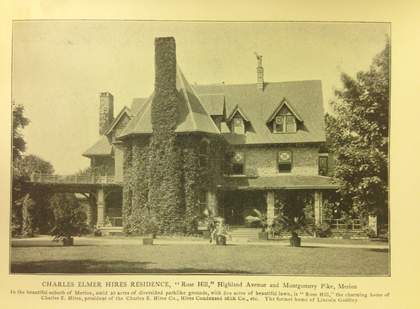

Fig.2

Photograph of Rose Hill, home of entrepreneur and pharmacist Charles E. Hires, Merion, Philadelphia

Published in Moses King, Philadelphia and Notable Philadelphians, New York 1902, p.74

Given this quantity of titles evoking coal country, Meryon, if read as Merion, registers as a unique aberration, but only in terms of its class connotations and land use. Although wealthier, Merion was still a town that had developed thanks to the construction of a railroad. However, Merion was on the Philadelphia Main Line, a commuter line that had facilitated the relocation of the Philadelphia elite over the course of the nineteenth century from the polluted, riotous and ethnically diverse city to the clean, calm and exclusive towns of the countryside. In towns like Merion, this elite built expansive country estates that initially served as summer houses but then increasingly became year-round residences: enormous structures on hilltops overlooking acres of land (fig.2). This land was wholly residential, developed in order to offer the wealthy an escape from the industries through which they had accumulated their fortunes – the very same industries and landscapes that Kline typically evoked in his paintings through his titles, palettes and forms.

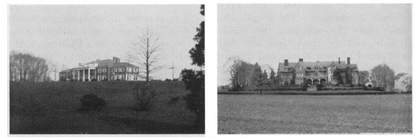

Fig.3

Photographs from George Langdon’s ‘Delimiting the Main Line District of Philadelphia’, Economic Geography, vol.28, no.1, January 1952, p.59

Meryon arguably contains all of these conflicts and contradictions. In Meryon Kline’s striking black and white palette and forms, which were developed as a way to picture urban and industrial America, are imported into this elite suburban context. It presents at once the rough industrial means and the ostentatious ends of Gilded Age America – the period in the late nineteenth century characterised by rapid economic growth and increased social inequality. If this enormous painting is approached as a more traditional landscape, what we can see is a massive, hierarchical, regimented structure that dominates the land and yet seems to shoot out of it. The exterior walls of this structure extend, in unbroken brushstrokes, past what would appear to be a horizon line, into the earth. In that their material make-up is identical, the manmade structure seems to be a ninety-degree rotation of the land, and yet its dominance is assured through its superior size and position. The land, which may be apprehended in the combination of an upright series of overlapping rectangles over a horizontal base, is expansive, and the vertical structure even more enormous. This composition resembles countless photographs of country estates on the Main Line, including the prototypical architectural views that the geographer George Langdon included in his 1952 essay ‘Delimiting the Main Line District of Philadelphia’ (fig.3).10 The prestige of this area meant that its perceived boundaries were ballooning by the 1950s, but Merion, Langdon found, remained a core of the Main Line: ‘Surveys of real estate offices appraising values of properties show that east of the railroad track in Lower Merion Township lie the greatest number of large estates and the location of the “choice” Main Line residences.’11 Almost a decade later, Kline could still evoke Merion in Meryon as the ultimate example of a phenomenon: the Philadelphia industrialist’s escape to the country estate.

Meryon

If Merion the place epitomises the industrialist’s escape from the city, Charles Meryon represents an ill-fated attempt to rescue the city from industrialists. Given its title and the fact that the painting takes the vertical format of a portrait painting, with the upright and horizontal rectangles emerging as a head and shoulders, Meryon could also be seen as a portrait of Meryon the artist. Rather than a portrait of the man, however, it will be shown here that Meryon can in fact be interpreted as a portrait of Meryon’s oeuvre of cityscapes. Despite the painting’s vertical format, it could be viewed as a landscape, but not the landscape of the countryside, where the horizontals of the ground and sky predominate. It is instead a picture of the rigorously manmade urban environment that Meryon also depicted, in which man has dictated both the flatness of the ground and the reach of the buildings into the sky. Meryon can thus be seen as metonymic portrait of an artist through his art.

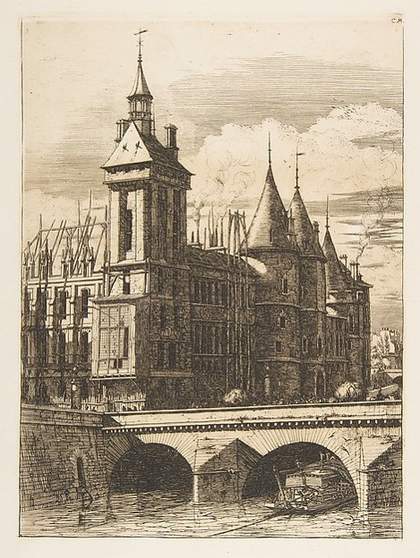

Fig.4

Charles Meryon

The Clock Tower, Paris 1852

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.5

Earlier state of Franz Kline’s Meryon, photographed in 1960 by Geoffrey Clements

Geoffrey Clements photographic negatives and papers, c.1950–2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

The only extended analysis of Meryon thus far was written by Harry Gaugh in 1985, in which he links the painting to the famous etcher. As such, it is worth quoting in full, including Gaugh’s points of visual comparison:

Meryon, an architectonic canvas from 1960–1961, reflects another nineteenth-century work, Charles Meryon’s prescient etching The Clock Tower, Paris [fig.4]. In fact, Meryon’s upright image stands as a bold amplification – sans peaked roof – of the tower’s top story. A photograph taken while Kline worked on the painting shows it to have been much blacker at first [fig.5]. In completing it, Kline introduced white apertures across the bottom that correspond in general position, albeit not shape, to the etching’s foreground bridge. Whites and contours were reworked in the upper form as well. Retaining the generalized orientation of the Parisian scene, Meryon takes on a structural yet animate ferocity, like that experienced at times in works by Goya, another artist Kline admired.12

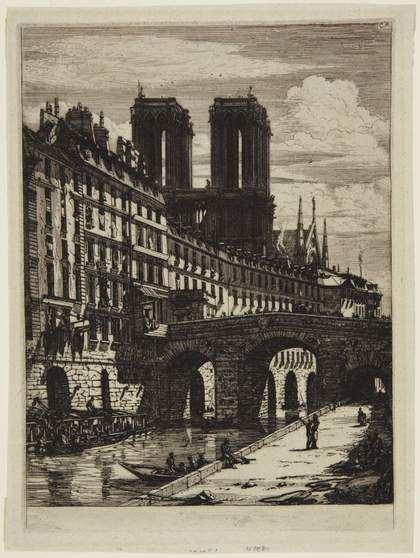

Fig.6

Charles Meryon

Le Petit Pont 1850

Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton

Locating a singular source for Meryon in one detail of one of Meryon’s etchings does not take into account the fact that the combination of towers and bridges of The Clock Tower, Paris constitutes a standard subject matter and organisational tool of vertical and horizontal thrusts within Meryon’s very small oeuvre. Rather than a detail from one painting, it is worth considering the compositions of Meryon’s works in general: similar sets of towers and bridges appear, for instance, in Meryon’s Le Pont au Change 1854, L’Abside de Notre Dame 1854 (both held in various collections, including the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) and Le Petit Pont of 1850 (fig.6). Arguably, Kline does not take inspiration from a particular work by Meryon. Instead, he seems to distil Meryon’s essential template for the organisation of his compositions, which is akin to Kline’s in content and form. This mode of visual analysis and distillation can be seen to be essential to Kline’s abstraction – and not only in reference to Meryon’s work.

In the other notable mention of Meryon within the published literature, critic and art historian Dore Ashton aptly calls Meryon ‘Kline’s tribute to that nineteenth-century etcher much admired by Baudelaire, in which Meryon’s noun, “tower”, is transformed into an active adjective: “towering”.’13 Meryon was said to begin his etchings from the foundations of the buildings upward, just as they had been constructed by their builders.14 The structure, whether tower or bridge, is therefore both finished and, in its directionality, a work in progress. The bridge, which often spans the entirety of the composition, as seen in Le Petit Pont, seems to stretch infinitely, as does the tower’s upward point. The dynamism of Kline’s structures in formation is shared by those of Meryon, even if Meryon memorialised medieval stone architecture and Kline focused on modern architecture in steel.

In the final stages of his creation of Meryon in 1961, Kline perforated what was previously the depicted structure’s solidly black base by adding areas of white. This made the lower section of the painting more bridge-like and also more similar to the upper section of the painting. In the structure is a black rectangle within a larger black rectangle within an even larger black rectangle, all slightly off register, which seems to suggest an oblique view of architectural forms and a consistent recession into space. The lower section, by contrast, seems to be represented frontally, with the black and white areas each evenly spaced and sized. If it is the quintessential vision of Charles Meryon that Meryon represents, then the two black flickers between the horizon line and the edge of the building on the right might be read as figural. Meryon often included figures similar to these in a scale relative to the buildings, to help give a sense of their enormous size (see figs.4, 5 and 6).

It was a set of outmoded structures and thereby a process of renovation that Meryon famously documented in his series of etchings of Paris, Eaux-fortes sur Paris, published between 1851 and 1854. The old, medieval Paris that Meryon monumentalised was being systematically demolished on the orders of President and then Emperor Napoleon III, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, and modernised under the direction of his Prefect, Haussmann. Large boulevards of building blocks were being erected, creating air and light, where there had been a dense, dark, intricately interwoven patchwork of narrow streets, rife with pollution, poverty, disease and periodic social and political unrest. This was real estate development, with huge fortunes to be made in contracts with the government and sales of much larger, grander apartments to the wealthy.

Like Meryon, Kline was an artist devoted to the city, having lived in New York for twenty years. Kline claimed that he could not live or work anywhere else, while other abstract expressionists abandoned the city for the countryside. This position was philosophical: ‘Hell,’ exclaimed Kline in an interview, ‘half the world wants to be like Thoreau at Walden worrying about the noise of the traffic on the way to Boston; the other half use up their lives being part of that noise. I like the second half. Right?’.15 As suburbanisation accelerated during the post-war period, luring away many abstract expressionists, Kline resisted, remaining committed to the city. The part of the city in which Kline first lived was New York’s bohemia, Greenwich Village, where the streets did not obey the orthogonal city plan of Manhattan, where the soft, marshy land had made building skyscrapers impossible, and where the rents remained relatively low, so that artists and others with limited means could nevertheless manage to live there.

Bohemia was thus a geography, morality and a circle of sociability at once, an area undeveloped by modern capital and thereby one from which to self-consciously and collectively challenge its reign, even though, as will be shown, there was inevitably a time limit on this counterculture and its activities. Meryon represented the archetypal nineteenth-century bohemian. The colour-blind master etcher was celebrated by Charles Baudelaire for his devotion to the fast-disappearing old Paris. He lived in poverty all the same and, suffering from repeated bouts of mental illness, would die in the asylum at Charenton.16 Kline invoked his name in Meryon just as the fabled bohemianism of abstract expressionism, including his own, was slipping away.

Within a decade, abstract expressionism developed from a marginal, oppositional, avant-garde movement into a national political treasure and propaganda tool in the cold war.17 Consider the lengthy account of Kline’s showdown with the French painter Jean Fautrier at the Venice Biennale of 1960 that was published in an Italian weekly news magazine, an English translation of which is kept in Kline’s personal archives:

Was it his [Fautrier’s] 1st prize at the Biennale that went to his head or the millions of hyperbolic whirlpoos [sic] swirling in his paintings? – neither one nor the other. His head has been spinning ever since he gave himself up to the bottle – which was long before he took up art. Here’s how it went: Fautrier is steeped in alcohol (though no drunker than usual) at Martinit’s in Venice when someone tells him that Kline has arrived. At this Fautrier flies off the handle, springs from the table as though shot from a gun, and dashes up to Kline, heaping him with insults: ‘Tete de c(ochon) parvenu! Qu’est ce que tu fais ici a m’en…! Va t’en aux Etats-Unis!’ (‘Pretentious swine! What are you doing here…! Go back to the United States!’).

Oh sweet sounds of the refined and ephemeral French language! ‘Dear friend,’ sighs Kline, profoundly touched (as a good Yankee he doesn’t understand a word of French): rather confused and with a quick smile he runs to hug the dear old man.

‘This damned creature hasn’t understood a thing,’ screams the enraged Fautrier, resuming his insults – this time in English – with renewed energy, hurling them in the face of the American, the winner of ‘one of those other minor prizes.’ ‘What are you doing here, damned Yankee – go back to the States – go to Hell – and learn how to paint,’ howls the Frenchman, his insults revealing an unsuspected linguistic versatility.

But with the words ‘Go to Hell’ and ‘learn how to paint’ Kline finally catches on and, being quite sober, retorts: ‘And you – what are you doing here in Italy – go home and make your pasticcios in France’ – a clear allusion to Fautrier’s pastry-like painting.18

If the rise of American abstract expressionism came at the expense of French schools of painting, whether figurative or abstract, so did, in part, the rise of the United States as a superpower at the cost of the European powers, including France, after the Second World War. This was a predicament that Charles de Gaulle was trying to reverse after he returned to power as President of the French Republic in 1958, by charting a path for France that was independent of the US and the Soviet Union during the cold war.

When French Minister of Culture André Malraux visited the White House in 1962 at the invitation of President John F. Kennedy – a dinner to which Kline was invited – culture, which had been a battleground, was submitted as common ground.19 Kline’s Meryon of 1960–1 anticipated this diplomatic attempt at reconciliation following the artist’s own skirmish with Fautrier. It was an explicit nod to French tradition that also demonstrated Kline’s education, which Fautrier had publicly called into question. And yet, in putting his learnedness on show in Meryon, Kline would confirm Fautrier’s insult: ‘Pretentious swine!’ (as it was translated into English). Even if it was true, as the article reported, that Kline did not ‘understand a word of French’, he could have understood some of Fautrier’s original phrase ‘Tete de c(ochon) parvenu!’ (‘pig-headed parvenu!’) , since ‘parvenu’ – meaning a person of humble origin who has gained success – is the same word in English. Fautrier was not wrong: from the French perspective, Kline and the other American abstract expressionists were upstarts, determined to create a national art, as seen in works such as Meryon, of universal and universalising significance.