The world presented in Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s 1977 photobook Evidence (Tate P14478–P14510 and P20292–P20294) is as much banal as it is frightening, comic as it is unnerving, ‘cold’ as it is ‘hot’. What we come to confront when flipping through the sequence of fifty-nine images in Evidence is a world in which the subjects, objects and actions of rationality have spiralled back and regressed into the circuits of catastrophe, disaster and regression. The examples in Evidence are legion: photographs of explosions on a cliffside; nuclear power plants on the California coastline; a landscape overtaken by a mysterious white foam. If there is a dystopian quality to Sultan and Mandel’s project, it is one that attests to a nightmarish scenario: a state in which man’s relation to nature is one of control and catastrophe, and where freedom appears to have been eliminated and science and technology have been deployed for the purposes of suppression and domination. This control over nature is explicitly suggested in the photographs of staged explosions and fires, but is also implicitly shown in the countless photographs of nature’s enmeshment and entrapment (fig.1).1 The world presented in Evidence appears to have been propelled by a contradictory vision of post-war America wherein enhanced production, improved standards of living and vibrant economic growth were also associated at the time with the destruction of human and natural life. The clearest example of this conflicting state of affairs was the cold war bomb shelter, a structure commonly stocked with the most up-to-date technology and provisions in order to survive a nuclear war.

Fig.1

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled 1977, printed 2001, from Evidence 1977

Tate P14495

Technological novelty and innovation is as much an expression of progress, then, as it is an expression of regression into barbarism. Sultan and Mandel’s Evidence is positioned on this apocalyptic precipice of technological change. This position aligns with the specificities of cold war culture: a moment marked by experiences of euphoria and control that competed with those of fear and anxiety.2 The work reads as an extreme counterpoint to the technological optimism associated with the cold war corporations from which Sultan and Mandel sourced their photographs: the Stanford Research Institute, NASA and RAND, among many others. The dystopian scenario present in Evidence, then, is shown to be a product of the increasing technocratic control over everyday life by the region’s major corporations and research bodies.3 This perspective follows on from literary critic and theorist Tom Moylan’s observation that in dystopian fiction, no single practice or policy can be isolated as the cause of this newfound horror – the whole system itself, from the state to its economy to its culture, is to blame for this disastrous situation.4

The metabolic rift

In Evidence, catastrophe can be read in a Marxist sense as a ‘metabolic rift’ between humanity and nature characterised by the progressive degradation of both the subject and the object of nature. In the third volume of Capital, philosopher and economist Karl Marx deployed the concept of ‘metabolic rift’ to describe the estrangement between capitalist society and its human subjects. The ecological contradiction between nature and capitalist society, Marx writes, wrought ‘an irreparable rift in the interdependent process of social metabolism’.5 Instead of producing a society where human subjects mediate, regulate and control the relationship between nature and humanity, capitalist social relations instead succeed in mastering nature technologically, economically and scientifically.

Fig.2

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled 1977, printed 2001, from Evidence 1977

Tate P14496

Fig.3

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled from Evidence 1977

As production intensifies, the very conditions of social reproduction governed by nature – such as shelter and sustenance – are progressively undermined. Exploitation of nature, Marx argued, ‘only develops the techniques and the degree of combination of the social process of production by simultaneously undermining the original sources of all wealth – the soil and the worker’.6 The photographs in Sultan and Mandel’s Evidence were produced in the midst and aftermath of this accelerating and degrading force, and in their project estrangement comes to read as a primary historical symptom of science and technology. In all of the photographs which feature the natural world in Evidence – whether a photograph of three hospital beds in an empty field (fig.2) or a controlled explosion in the middle of the desert (fig.3) – something seems wrong or awry within the scene. Whether depicted explicitly or implicitly, violence towards nature is a central thematic throughout the images, and is framed as a force that continually and cyclically breaks the social bond.7 The metabolic rift dramatised by Sultan and Mandel’s photographic sequence is readable at the level of the body and the landscape where science, technology and their attendant rationalisation violently separate and dislocate the subject from nature. This activity takes on a mythic form: to quote philosophers Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer from their Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), the domination of nature is ‘paid for with the estrangement of human beings from the dominated objects’ insofar as it forces ‘the relationship of human beings, including the relationship of individuals to themselves, [to become] bewitched’.8

In an entry from their working journal at the time, Sultan and Mandel framed their photobook Evidence as a weakening or dismemberment of the capacities of the senses. The project details ‘the amputation of human sensitivity’, Sultan and Mandel wrote, ‘into the service of technological development’.9 At the root of my argument is the troubled ‘nature’ of photography, a practice that since its very beginning has oscillated between the discourses of nature and culture. The earliest example of this is Henry Fox Talbot’s illustrated book The Pencil of Nature (1844–6), a work that in its very title foregrounds photography’s difficult status as a practice suspended between nature and culture.10 Sultan and Mandel’s project represents nature not as physis (or ‘first nature’), as West Coast photography in the mode of Edward Weston and Ansel Adams is often categorised as enacting. Rather, the work confronts it as an estranged ‘second nature’. For Sultan and Mandel, the image of nature in its picturesque form is a deceptive fiction, and the task of their project is the attempt to articulate the metabolic rift that persists between humanity and nature.11 Evidence is not founded on an ideological fantasy that opposes technology to nature, but rather attempts to find a language to articulate the second nature of society. The world of second nature, Adorno suggests, is a world of estranged things, the perception of which requires a change in perspective.12 The artist, historian and writer must adopt ‘strategies of indirection’, to cite a literary method outlined by Fredric Jameson, that take hold of this estranged and petrified image.13

The nature/culture collapse

With respect to the regional context of California, historian and urban theorist Mike Davis’s numerous writings on Los Angeles are helpful when thinking through the nature/culture collapse present in Evidence. Davis has coined the phrase ‘ecology of fear’ to describe the catastrophic urbanism of post-war society, typical of Southern California, where natural, technological, socio-political and economic disasters converged in a complex constellation, one that traversed the conventional nature/culture configuration that viewed the relation as harmonious and without contradiction. What is distinctive about California is not simply the fact that disaster and catastrophe became routine – intricately woven throughout the region’s social, economic and environmental texture – but rather the peculiar way in which California’s natural disasters were linked to its urban changes: for instance, the strong correlation between population increase and the number of wild fires. The thematic of catastrophe therefore reads as a valuable model for historians in the present day, for the model comes to track national discontents and local histories, and mobilises deep-rooted cultural predispositions.14

The nature/culture collapse figured in Sultan and Mandel’s project represents, at its root, a social rift where humanity is alienated from nature, producing, as we have seen, an estranged and defamiliarised second nature.15 This artificial nature leads to the formation of new demands and needs that are dictated by the requirements and desires produced by the commodity. The second nature produced by industry, although animated, reads to Adorno as an ‘alienated, dead world’, a ‘charnel-house’.16 Second nature, under modern industrial capitalism, transforms into a type of first nature.17

Evidence, then, should be read through its dual structure: the project is both the sedimentation of the work’s content – the technologies of science spiralling into catastrophe, danger and disaster – and a constellation of the work’s form, one that is elusive, mythic and inexhaustible.18 What is innovative about Sultan and Mandel’s Evidence is how the nature/culture collapse is echoed in the collapsed interpretative coherence of the work as a whole. The project mobilises the images of objectivity and rationality but their arrangement does not rely on a logical and coherent narrative sequence; instead, the work unfolds within a model of irrationality that multiplies confusion every time a new image is encountered. Sultan and Mandel’s epistemology exhibits an antithetical relationship to the programme of objectivity and rationality that constitutes the very nature of evidence. This argument aligns with the reading of instrumentalised science in Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment, in which the project of science and technology is founded on the domination of both nature and human beings. As much as one would like to establish a consistent interpretive frame for Sultan and Mandel’s Evidence, the work is premised on showing how such interpretive systems continually break down. It is only from this vantage point of disintegration and irrationality that we are able to perceive the specific critique advanced by Sultan and Mandel’s work.

Fig.4

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled from Oranges on Fire 1975

Fig.5

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled from Oranges on Fire 1975

This collapse of nature and culture and its figuration as catastrophe finds its comical embodiment in a slightly earlier project by Sultan and Mandel, their 1975 billboard Oranges on Fire. This work combines two psychically charged components of the Southern Californian imaginary: the utopian bounty of a California citrus harvest – a bunch of oranges – and a nod to one of California’s many cyclical natural disasters: wild fire. Sultan and Mandel staged this photograph, rendered it as an illustration and displayed it on a billboard in the streets of San Francisco and Santa Cruz in the summer months of 1975, at the height of wild fire season. In preparation for their billboard, Sultan and Mandel undertook extensive research into the representation of ‘oranges’ and ‘fire’ in the region. They collected a number of found photographs and staged a series of photographs in preparation for the work. One staged ‘experiment’ showed over twenty oranges in a barbecue set on fire with gasoline. Another image – one of the many found photographs Sultan and Mandel collected – showed a California bungalow engulfed in flames (fig.4). A third, staged image showed Mandel holding a poster of a naked woman being massaged by a man, with the top half of the poster on fire. If this was not weird enough, the final image in Sultan and Mandel’s ‘experiments’ shows the former in a white coat in what looks like a school science laboratory, pointing a torch at a row of oranges (fig.5). The duo’s imagery for this particular project is as bizarre and eccentric as it is catastrophic and comic.

Fig.6

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled 1977, printed 2001, from Evidence 1977

Tate P14500

To return to Evidence, Sultan and Mandel’s project emphasises how the destructive forces of modernity are primarily embodied through the newest forms of military-grade technology. Yet in Evidence the artists not only represented these destructive forces but also suggested the possibility of viewing the world anew, in parallax, from a displaced perspective. Created in the enduring shadow of the Vietnam War (1955–75) and in the wider context of the cold war, Evidence dramatised how memory was viewed as a problem: a persistent source of discomfort and unease. As I have demonstrated elsewhere in this In Focus, these cold war anxieties concerning the subject’s relation to the future were just as much anxieties expressed in relation to the status of the past.19 The central figure who embodies these fears is the research scientist of the 1950s and 1960s – the most prevalent figure in Evidence – who is almost always portrayed as if attending to the breakdown of machines or as an unwitting casualty of the machine’s dominance (fig.6).

The body as experimental subject

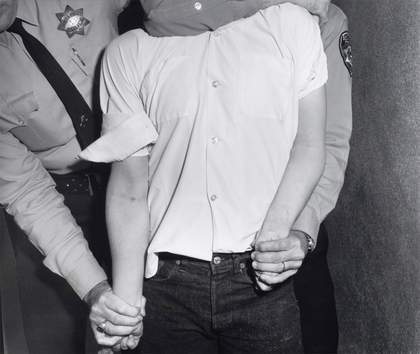

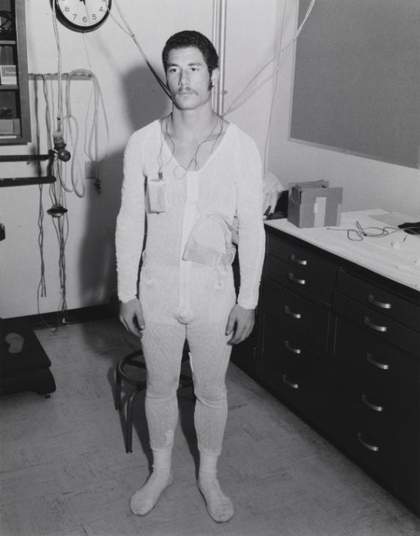

The California research scientist that recurs in Evidence is a type recognisable by features such as the short haircut, white shirt, narrow tie and dark horn-rimmed glasses. On the other hand, there is another figure, the inverse to the research scientist: a body restrained by the police or pushed to the extremes of science and technology. This double articulation of both progression and regression figures the body on an eccentrically strange and alien register. The body is presented as a terrain on which the forgotten and not easily decipherable aspects of human experience and barbarism are deposited. The new technologies, objects and buildings presented in Sultan and Mandel’s Evidence, although ciphers of novelty and progress, are read counter-intuitively, and are linked, simultaneously, to the marks of injustice and oppression.

Fig.7

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled from Evidence 1977

Fig.8

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled from Evidence 1977

Fig.9

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled 1977, printed 2001, from Evidence 1977

Tate P14492

In one sequence, for instance, we see a photograph of a man’s torso as he is restrained by two Santa Cruz police officers (fig.7). The man resists while the officer on the right places him in a chokehold. The image is framed in such a way that we are unable to see the subjects’ faces. On the facing page of the photobook is a photograph of monkey’s body being restrained by a gloved hand (fig.8) – the body looks somewhat, but not entirely, human, perhaps making a distinct corporeal connection between the restraint enacted by the police and the control of animals by scientific researchers. It is as though Sultan and Mandel’s subjects have fallen into a magnetic field of destruction. This expression of violence has a particular valence in Evidence: it appears as an expression of self-destruction, control and domination – comic forces, seen in American slapstick, that propel the subject into a destructive orbit (fig.9). Similar to the way in which Charlie Chaplin’s body is violently manipulated in the 1936 film Modern Times, the bodies in Evidence appear to have entangled themselves in technology’s destructive web.

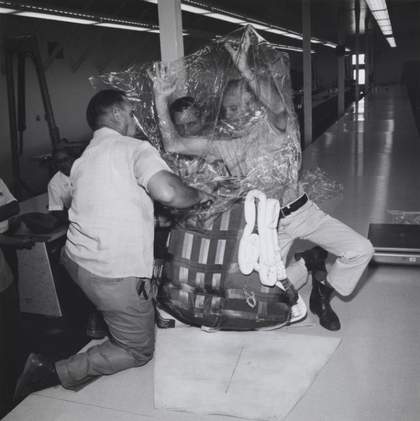

One of the most disturbing aspects of Evidence is its capacity to fuse the bodies of these figures – arms, legs, torsos – with the machines’ technological apparatus, creating part-objects. Furthermore, Evidence displays a code made up of gestures that possess no symbolic meaning in isolation, but rather derive their meaning from the experimental combination within the sequence. The gestures found in Evidence are curiously enigmatic, yet they are almost always catastrophic in their truth-content. Catastrophe unfolds immanently, revealing itself within the work through often darkly comic scenarios. For instance, the group of photographs in the middle section of the sequence shows the forms through which men experiment, test and push the terrains of technology and machinery to their utmost limits. We see photographs of a man attending to a whirling machine, three men in suits bending over a sprinkler, an individual sitting in what looks like an air traffic control centre, and a man wrapping two others in plastic film. Sultan and Mandel offer descriptions in their preparatory notes for the Evidence exhibition, held at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1977 and featuring a larger selection of photographs than were included in the book:

man smashing object against machine, linear explosion and flag, monkey in the hand, man watching small explosion, power plant model between two elevators, nine businessmen standing by a building in construction, people pruning trees in a greenhouse, man holding weeds, hospital beds in the field and three people, first aid rescue practice, man with stomach truss stretching straps, man measuring man, man contemplating tripod wagon, man in tunnel propeller, astronaut model lying on the carpet, man’s hand, ruler on the wall.20

The subject shuttles between those who control and those who are controlled. The body represents a cipher on which control and domination, trauma and suffering are inscribed in the most palpable, strange and barbaric manner. As the body is increasingly invaded, probed and studied in Evidence, it appears more and more alien, distanced and strange. The body emerges, here, under the regressive mark of barbarism.21

Gendered subjects and the ‘new man’

Sultan and Mandel’s exhibition notes also served to declare overtly the gendered stakes of Evidence. The titles that the artists included in their personal notes on the work often conjure a distinctly masculinist emphasis:

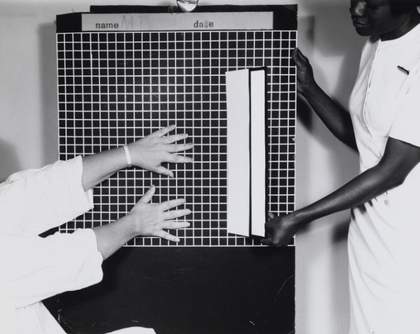

men standing next to sphere; man in tunnel trapped by propeller; man with flame retardant bag over his head; man with four small planes; woman drawing cube in computer room; five military men in a box, no step; man pointing to lines in a black man’s head; etc.22

Fig.10

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled 1977, printed 2001, from Evidence 1977

Tate P14485

Fig.11

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled from Evidence 1977

Their list reads as a generic and descriptive compendium. Most elements begin with the word ‘man’ or ‘men’. When gender is not invoked, the descriptions are associative (‘metal cylinders hanging like sausages’), whereas others are structured using the definite article, such as ‘the hand’ and ‘the blob’ – two names that refer to the titles of science fiction B movies. The majority of the titles, however, frame the scenarios as distinctly masculinist. There are only four women pictured in Evidence, and when they are featured they have a peripheral role (see figs.10 and 11). The sequence articulates a history, to quote Sultan, of ‘what men do in nature’ – which is to say, a history of control and domination.23

The gendered pursuit of scientific objectivity, as Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison have argued their study Objectivity, is always also the pursuit and consolidation of the scientific self: ‘The mastery of scientific practices is inevitably linked to self-mastery, the assiduous cultivation of a certain kind of self’.24 In a different context, historian of photography Blake Stimson has described how the photographic medium serves a central role in the production of subjectivity. In the post-war period, photography was entrusted not only with the creation of a new vision but also of a ‘new man’. This new man, Stimson argues, is representative of ‘a new political subject that could comprehend, negotiate, and navigate the postwar sense of obsolescence of modern political structures and passions, the pressing fear of nuclear war, and the accelerated globalisation of the economy driven by technological advance and the new entrepreneurial Pax Americana’.25 The new man that Stimson describes is different from the one that had been ushered in at the turn of the twentieth century by the systems of efficiency proposed by Frederick Taylor and Henry Ford. If the rationalised new man of Taylor and Ford was regulated and surveyed by management to ensure an ever-efficient production line, Stimson’s new man is a technocrat whose technological expertise is combined with an obsession with bureaucracy and a lack of emotion. In post-war California this new technocratic subject was the product of military Keynesianism: the set of policies based on the position that increased government spending on the military, from municipal, state and federal funds, would lead to increased economic growth in the region.26 This demand for innovation in aeronautics and electronic warfare systems demanded a new, technocratic workforce.

Fig.12

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled 1977, printed 2001, from Evidence 1977

Tate P14499

In the context of Evidence, this ‘new man’ cuts a particular figure. California has spawned a whole host of archetypal characters and fictions during its short history: the frontiersman/rancher; the gold-rush ‘forty-niner’; the Hollywood producer and actor; and, more recently, the defence research scientist or engineer (see fig.12).27 The region encouraged oneself to form one’s identity as a fiction – in the words of writer Rebecca Solnit, to construct oneself as ‘a character, a hero, unburdened by the past’.28 By 1963 there were seventy thousand scientists and engineers employed in the region, mostly working in the defence industry. According to historian Kevin Starr, these individuals had a generic appearance:

Moving from the suburban homes and families each morning by automobile and freeway to the cold war campuses where they worked, look-alikes in their short-haircuts, white shirts, narrow ties, and dark Robert Q. Lewis-style horn-rimmed glasses, they spent the work day bent over their desks or drawing boards or gathered around seminar tables discussing one or another cutting-edge problem of missile engineering and/or deployment.29

Fig.13

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel

Untitled 1977, printed 2001, from Evidence 1977

Tate P14484

In Evidence, however, the sense of technical progress is consistently undermined and undone. On the one hand, each ‘man’ reads as a cipher of objectivity, elevated as a master of nature, yet this same figure also appears deadened and mindless. Sultan and Mandel’s ‘man’ is simultaneously the active subject and the object of nature.30 Take, for instance, the ninth photograph in the sequence that shows a man in white underclothes with wires connected to him (fig.13). There is something incredibly foolish, if not obstinate, in this series of photographs. As mentioned above, this violently obstinate relation is not one of symbiosis, where humanity regulates and controls its metabolism with nature, but rather a terrain where control and domination, trauma and suffering are inscribed on both the body and the landscape in the most manifestly alien and violent manner. Evidence documents the irreparable rift between humanity and nature.

It is as though the presentation of ‘evidence’ in Sultan and Mandel’s project was staged in order to interrogate and consider, if not re-interrogate and reconsider, the means through which events – whether fictional or historical – are made material and are interpreted through photographs. Evidence functions ironically as an assessment of the rationalism constitutive of each image, critiquing the very foundations of objectivity and positivism. In a sense, the project forcibly masquerades as historical evidence at the same time that it casts doubt on the authority of that evidence and its relation to the language of photography, if not the wider operations of the workings of history. In this sense, Evidence engages in what philosopher Michel Foucault termed a ‘critical genealogy’, by capturing and highlighting the ways in which photographic evidence is staged to serve institutionalised power.31 Sultan and Mandel’s project does not release evidence in an open field of interpretation – there is no such thing – but rather, their project reworks the idea of evidence and its imagery within the history of California.

If history written by the victors (corporations, police and state) reads as linear and objective, propelled by a steady and singular rhythm, the counter to this could be that history, when written by the defeated and dispossessed, appears multi-directional, complicated and polyrhythmic. On this final note, Sultan and Mandel’s project permits the viewer to read history in a different key, advancing a slight shift in perspective. This shift opposes the dominant mode of perception that views the institutional domains of the police, the state and the corporation as omnipotent and infallible. In a sense, the reader of Evidence is asked not only to make sense of each photograph but also the relations between them through a system of relays and delays, interruptions and anticipations, successions and simultaneities which advance a new space-time configuration. This configuration not only recalibrates the subject’s relation to the past, but also advances a new and critical perspective on the future.