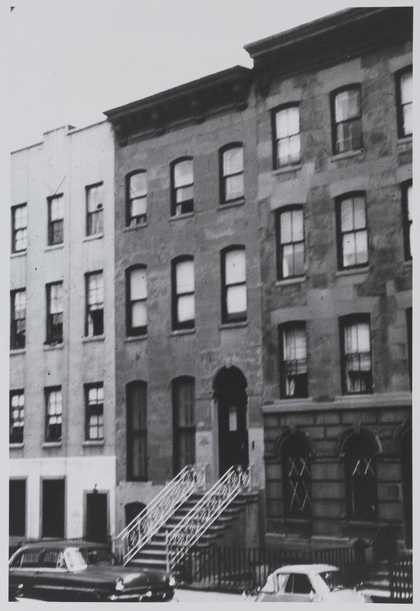

Fig.1

Exterior of Louise Nevelson's townhouse, 323 30th Street, New York City c.1956

Unidentified photographer

Louise Nevelson papers. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

In 1945 Louise Nevelson moved to a new house on the east side of Manhattan. The property was a four-story Brownstone terrace at 323 East 30th Street (fig.1) in the area known as Kips Bay, the neighbourhood between Murray Hill and the East River. She lived there until late 1958 or early 1959. It was in this house that the first of her ‘walls’ was conceived and executed.1 Many viewers have understood Nevelson’s art to be closely tied to the particularities of place. To British critic John Russell, writing in the early 1960s, the close connection between Nevelson’s work and her New York location were patent. They were, he thought, ‘a New Yorker’s contribution to art. They use the materials which that great city provides in super abundance, as a result of the day-long dismantling of unwanted buildings that goes on all the time’. For Russell, the emotional impact of Nevelson’s sculpture ‘derives from the tension between the pure formal values which Nevelson inherits from European classical painting and the capacity of living art to redeem and regenerate what society has discarded’.2

Poetic responses to Nevelson’s art have equally understood the urban origins of its language. In a long poem written in 1958 by Parker Tyler, co-editor of the surrealist magazine View, Nevelson’s Moon Garden Plus One exhibition held earlier that year was used to evoke a ‘phantom city’. For Tyler, the location of Nevelson’s sculpture was unambiguous. ‘Is this New York?’, the first page of his verse asks, before answering, ‘Who but the blind shall ask?’3 A later poetic homage of Nevelson’s work was equally specific in positioning her sculpture among the ‘ziggurats of Manhattan’.4 As these writers recognised, the forms of Nevelson’s early constructions, such as Black Wall (Tate T00514), were shaped by the place in which they were made – by Nevelson’s house, and the city of which it was a part. Above all, the materials of Black Wall can be understood to echo the tumultuous context of urban renewal that eventually required Nevelson to leave her neighbourhood.

Fig.2

Jeremiah Russell

Louise Nevelson’s house on 30th Street, New York c.1955

Louise Nevelson papers, c.1903–1979. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

After the death of her parents, Nevelson’s brother agreed to purchase a New York property for Louise from the proceeds of the family estate.5 ‘No more than a week passed after I returned from Maine when Ralph found the house’, Nevelson later remembered.6 Her friend Ralph Rosenberg lived nearby, on the corner of 30th Street and Lexington Avenue, and like Nevelson, exhibited with Nierendorf Gallery.7 To help renovate the house, Nevelson borrowed money from Karl Nierendorf while Rosenberg helped with structural repairs.8 Amid the Victorian interiors, walls of raw brick injected a note of bohemianism into the otherwise gentile décor.9 Photographs of its grand Victorian rooms suggest its role as a kind of showcase for her sculpture, an exhibition space of works by an artist for whom sales were few and far between (fig.2).

Over the next decade the property became an artistic hub for the circles of the New York art world in which Nevelson moved. Several of the public discussions known as the Four O’Clock Forums, which Nevelson co-sponsored, were held in the space. Beginning in 1953, participants in these discussions included Philip Guston, Willem de Kooning and Richard Lippold.10 Other artist groups that met there included the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors.11 The space even occasionally hosted public cultural events, such as a 1955 musical performance presented by the Inter-Arts Committee and the League of Present Day Artists.12 ‘That house was used very well for art’, Nevelson later recalled. ‘It was almost like a clubhouse in that sense.’13 Nevelson herself had briefly rented a space in the Tenth Street Studio Building, and like the nineteenth-century highly social studios that this building had once housed, her Kips Bay space provided a hub for Nevelson to build her own networks in the New York art world.14

After less than a decade in her house and studio, Nevelson was faced with eviction. In late 1954 New York’s Committee for Slum Clearance announced that three blocks between 30th and 33rd Streets would be demolished for redevelopment. The 9.44-acre area contained about 849 houses, and was located between First and Second Avenues, west of the Bellevue Hospital on the East River. These three long blocks of mainly low-rise terrace houses are visible in the right corner of an aerial photograph taken by the city in 1953 (fig.3). Under Title I of the National Housing Act of 1949, American cities were able to forcibly acquire properties in ‘blighted’ neighbourhoods for ‘slum clearance’. Using a combination of city and federal funds, parcels of land were sold to private investors at a fraction of the cost of its value. The developer became responsible for the relocation of tenants and the clearing of the land, but by way of an incentive to complete the works quickly, remained responsible for paying city taxes on the land.

Fig.3

Aerial view of Bellevue Hospital and Kips Bay, New York, 24 September 1953

New York City Department of Records

Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives

Known in its early stages as the NYU-Bellevue development after the adjacent medical centre operated by the university, official descriptions of the area emphasised that it was ‘congested and dilapidated, [containing] old and obsolete loft and small storage buildings with inadequate traffic, loading and parking areas’.15 Led by Robert Moses, the project was justified by the calculation that more than half of the properties in the area were ‘deteriorated’ or ‘badly run down’. But the same report also admitted that residents of the area were ‘accustomed to living conditions on the site’.16 For Moses, however, such signs of a functioning community had to be sacrificed for higher goals. ‘When you operate in an overbuilt metropolis’, the single-minded pioneer of urban renewal explained, ‘you have to go at it with a meat-ax.’17

Before the bulldozers cut their way through Kips Bay’s thicket of old buildings, it was not really quite accurate to even call it a slum. According to the New York Times, ‘second generation immigrant families’ had already ‘began to move away as middle-class families started buying some of the old houses’.18 This was a gentrification that Nevelson herself had participated in. In the eyes of one critic of urban renewal, Kips Bay was ‘no more a slum than any other patch of real estate in the mixed metropolitan belt that is central Manhattan’.19 Its ‘blend of old tenements and stores’ represented that kind of ‘sprinkling of slum miscellany’ that provided New York neighbourhoods with ‘charm’.20 The dilapidated form of Nevelson’s cobbled-together sculptures could be said to evoke some of that mood, the romantic ambiance that might well have initially attracted Nevelson to Kips Bay.21

It is little wonder that Nevelson was known to refer to her constructions as ‘living communities’ in which ‘each niche lives and encloses its own life’ and ‘each cell strengthens and supports its neighbours’.22 In the same interview, Nevelson’s biological imagining of her sculptural form also emphasised its representation of flux: you can ‘place the cells wherever you wish’, she explained, capturing the capacity for her boxes to be recomposed. ‘You are restructuring, not destroying, because life is in the parts as well as the whole.’23 If Nevelson’s art is understood in relation to the changes that were wrought to the fabric of her own community, Nevelson’s terms echo those put forward by urbanist Jane Jacobs in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), whose criticisms of urban renewal hinged on her understanding of the ‘organised complexity’ of the city as a social organism.24

Although the Kips Bay project had not engendered the same community protest as other evictions, where picketing ‘housewives mounted guard around … abandoned frame buildings and stubbornly refused to move’, more modest community efforts to preserve the fabric of their community were evident.25 In late 1957 the Chapel of the Incarnation – located a block northwest of Nevelson’s house and studio – held an exhibition for local parishioners to preserve the material traces of their disappearing community by exhibiting in the church ‘any family heirloom or relic, any treasured bit of handicraft’.26 No less than these modest efforts to bring together the material remnants of the local community, Nevelson’s Black Wall should perhaps also be understood as preserving aspects of the ramshackle neighbourhood from which she and her neighbours were evicted.

Fig.4

View of NYU-Bellevue project progress, 1957. Reproduced in Slum Clearance Progress, Title I, NYC, New York, 1957, p.9

Once the private developers took possession of the Kips Bay site, progress was slow. They ‘neither cleared the land nor maintained the existing housing, and made little effort to assist people relocating’, turning the site into a temporary ‘profitable “slumlord” operation’.27 When Robert Moses visited in mid-1956, the bleak scene made front page news: ‘windows had been broken and other vandalism committed in vacated apartments while families not yet relocated continue living in adjoining flats’.28 Only seven buildings were vacated and demolished as the developer dealt with financial problems. By May 1957 the project had progressed further, with 56% of the tenants relocated and 35% of the site cleared.29 A contemporary government report published in mid-1957 reproduced an aerial view of the site showing this stage of its demolition (fig.4). But Moses remained dissatisfied with the speed of the project, and in June 1957 he transferred the project to Webb and Knapp, the company of real estate mogul William Zeckendorf.30

Fig.5

Aerial view of NYU-Bellevue project in progress (looking north), 3 November 1958

New York City Department of Records, Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives

Fig.6

Aerial view of NYU-Bellevue project in progress (looking south), 3 November 1958

New York City Department of Records, Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives

In March 1958 the New York Times reported that ‘tenant relocation’ for Kips Bay Park was in its ‘final stages’.31 Nevelson did not manage to purchase her new studio until September 1958.32 Close examination of photographs taken from the north (fig.5) and the south (fig.6) in November 1958 shows Nevelson’s property still standing. But buildings behind her house appear to have been demolished, and one or more properties on 30th Street appear to have been cleared, a stark gap in the streetscape that could not have helped but remind the artist of her own precarious position. As she owned rather than rented her house on East 30th Street, and was therefore entitled to receive compensation, Nevelson was undoubtedly in a more powerful position than many of her neighbours. But the fact that she stayed in her house as those around her were emptied and razed must have left a powerful impression on the artist. Uncertain of exactly when she would she would be finally forced to leave, though still unavoidably conscious of the eventuality of her eviction, it was in this context that Nevelson began to make her soon-to-be trademark timber constructions.

The connection between this history and her sculptures has been infrequently observed, but in the 1960s one writer did seek to connect Nevelson’s eviction with the emergence of her new sculptural language:

With a time limit on her stay, she hunted for another studio while working with desperate urgency to finish the pieces for her Moon Garden Plus One show in 1958 … As she was losing one shelter she constructed a hundred others from the many mansions of a creative consciousness. She packed for moving, throwing away the furniture of the past, making room so she could see to build with the boxes that held her future.33

The terms here might be a little overdone, but the underlying claim seems convincing. It is similarly noteworthy that when Nevelson recounted the expansion of her practice in this period, it was the urban grid that served as her metaphor. ‘I attribute the walls to this’, she explained. ‘I had loads of energy. I mean, energy and energy and loads of creative energy … at that time if I’d had a city block it wouldn’t have been enough.’34 Nevelson’s walls were produced amid the boarded-up buildings and demolition of urban renewal, facing the deferred but looming reality of having to pack herself up and leave. In a 1957 article Life magazine reported that Nevelson’s sculptures included material ‘scavenged’ from ‘demolished houses’.35 ‘I pick up old wood that had a life’, was how the artist once described her materials, showing her appreciation of the social resonance of her scrap materials.36 Given that several of the boxes in Black Wall already existed in mid-1958, before Nevelson moved to her new studio, it seems likely that the work included material remains of the lives of her neighbours and of the disappearing neighbourhood.

In Kips Bay, even before its old timber-framed buildings were transformed into piles of scrap, departing residents left behind a range of detritus through which Nevelson is known to have rummaged. ‘For years she used to scavenge New York’s darkened streets, finding there at night old broken arms and legs of chairs, orange crates and 2-by-4s and rackets without strings’, claimed one later account.37 Nevelson was not alone in recognising the aesthetic possibilities of demolition. ‘In the New York area, the astute scavenger soon found the razed buildings were a gold mine’, the New York Times explained in a 1960 article.38 Following in the footsteps of such thrifty rummaging, Black Wall preserves the architectural remnants and discarded contents displaced by urban renewal.

But more than simply assembling the materials of slum clearance, Nevelson’s walls represented a kind of displacement or, as the above account terms it, an expression of her ‘mansions of creative consciousness’ facing eviction.39 Like overstuffed rooms in an ever-expanding dollhouse, the boxes proliferated and began to consume her terraced house. ‘Divisions between walls seemed to dissolve in an endless sculptural environment’, described Hilton Kramer in the late 1950s. ‘When one ascended the stairs, the walls enclosed the visitor in the same unremitting spectacle.’40 Directing the loss of her own house into the obsessive production of walls for her forthcoming exhibition, Nevelson created a miniaturised architectural fantasy that flourished even as the buildings around her tumbled.

Fig.7

1st Avenue between 30th and 33rd Street. New housing development, Kips Bay (looking south), 17 April 1961

From the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York

Fig.8

Louise Nevelson

Black Wall 1959

Painted wood

2632 x 2165 x 648mm

Tate T00514

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016

A photograph of the completed Kips Bay Project (fig.7) suggests that Nevelson’s Black Wall (fig.8) finds its architectural correlate not in the massive filing cabinet towers and surrounding space of I.M. Pei’s design for the area, but in the dwarfed row of terraces that provide the distant backdrop for the redevelopment. These were the facades that Nevelson would have once seen out of her front windows, the architectural reflection of her own house. The jumbled details of this streetscape are the built forms to which Nevelson’s sculpture relates. ‘Their imaginative effect, if one projects their scale and pictures oneself one inch high, is similar to the experience of walking through a city alone at night’, observed critic Christopher Andrae of Nevelson’s walls, a description that suggests the capacity of these constructions to evoke Nevelson’s own passage through the darkened streets of New York.41 Ignoring the more controlled grids of slum clearance, Nevelson’s sculpture celebrates the disorderly, the worn-out and the obsolete – a kind of urban montage that stubbornly revels in an architectural language of the past.

The connection between the city and her sculpture was one that Nevelson would come to foster. ‘I see New York City as a great big sculpture’, she explained. ‘I saw the Empire State Building when it was going up. So many buildings that have come up and gone down. And the skyline is in constant change.’42 Like New York City itself, Nevelson’s constructions were made possible by waste and demolition. But it is also notable that her example is not the sleek Lever House (1952) or the Seagram Building (1958), but the more outdated glamour of New York’s famous Art Deco skyscrapers. Eschewing the sleek lines of the International Style, the decorative details and stepped profile of Nevelson’s wall suggest entirely less up-to-date architectural referents – like the jazzy angles and scallops of the Chrysler Building or the florid carved details of Grand Central Terminal, buildings both visible from the backyard of Nevelson’s East 30th Street residence.43

In addition to its evocation of the artist’s nocturnal scavenging, the matte black finish of Black Wall suggests a further connection to the image of burnt timber that was so central to the rhetoric driving slum clearance. Chief among Robert Moses arguments for urban renewal projects was that tenements were dangerous ‘fire traps’.44 The disposal of building waste had become an acute problem for the city by the late 1950s.45 From January to August 1958 the city burnt the scrap timber from 6,255 dwellings within the city or on nearby barges.46 Descriptions of Nevelson’s black constructions could sometimes evoke the image of a burnt city. In 1959 James Schuyler thought her works looked like ‘the grotesque and soot-containing icicles after a winter fire’.47 Another later description imaged her walls as ‘vast columbaria’ for the ‘human ashes of an entire city’.48 Architectural Review described Black Wall as ‘soot black’ in colour.49 As much as this work saves the fragments of a disappearing New York, its blackened finish equally suggests its incineration.

In the 1960s the impact of urban renewal on downtown artists created a situation of mounting urgency. In June 1961 many major figures in the New York art world announced that they would strike over the eviction of artists from their downtown loft studios. It was in this context that artist Sacha Kolin reached out to Nevelson to discuss reviving a discussion panel on ‘artists’ housing problems’.50 The earlier event to which Kolin’s letter, now among Nevelson’s papers, refers was probably that organised under the auspices of the Society of Young American Artists at the Riverside Museum in 1957, which focused on the large-scale slum clearance of the Lincoln Square neighbourhood. Along with Nevelson and Kolin, architect Fontaine Jones appeared on the panel, arguing that old buildings should be reused for studio space.51 But a note on Kolin’s letter indicates that Nevelson was ‘not available’ for its proposed reprise. Nor does she appear to have agreed to participate in the strike to which so many other New York artists lent their names, which was scheduled to begin on 11 September 1961.52

As her career was finally taking off, going on strike was perhaps not what Nevelson had in mind. ‘Although Louise joined the Artists’ Union’, her biographer has claimed, ‘she remained bored by politics’.53 Certainly, there was a time when the idea of her art serving direct political ends was, for Nevelson, like many abstract artists of the 1950s, profoundly unappealing. ‘I would not want to spend two minutes, much less months on an unknown prisoner’, Nevelson declared in 1954, referring to a sculpture competition to design a memorial on this overtly politicised theme in which so many of her peers participated.54 But a statement from around 1961 does indicate Nevelson’s understanding of the social potential of her art. ‘The constant changes of our time both in science and socio-political struggle have shaken to the very foundation man’s concepts and beliefs’, she wrote. ‘Sculpture in its concrete ideas is here as a confrontation.’55 Black Wall may not quite confront the politics of slum clearance, but its salvaged materiality can be seen to stand against the aesthetic values of bulldozer modernism.

Some of these issues would find expression later in Nevelson’s career. Representing Artists Equity at a 1964 conference, for example, she contributed to several panels that suggest her engagement with issues concerning art, government and urban planning – including a session entitled ‘Plans as Non-Plans in Cities’, for which she spoke alongside architect Paul Thomas and pop art pioneer John McHale. In 1964 Nevelson publically criticised Robert Moses’s failure to include contemporary art in the program of the New York World’s Fair.56 Like many artists, Nevelson also participated in the Artists’ Protest Committee’s Peace Tower in Los Angeles in 1966.57 And the problem of studio accommodation for New York artists was an issue to which she would eventually lend her voice. Here is Nevelson describing the attitude of New York City to its artists in a 1971 interview: ‘They tear out a chunk of artists like a nest of rats, and throw them out of an environment, tear down their buildings.’ This was a history within which she had come to understand her own eviction, as she explained:

They did it to me on East 30th Street. Look, New York became the center of the art world in the shortest time in the history of art … The irony is that New York treats its creative people like 10th rate citizens. If politicians are so stupid and shortsighted that they make creative minds leave New York, it will become a ghost city. I lose my cool over this.58

Nevelson’s views on New York’s ever-changing urban environment and its impact on artists are not without their inconsistencies, but the development of her walls against the context of slum clearance provides further impetus for understanding her work within the fields of neo-dada and junk sculpture of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Her engagement with the built environment certainly evidences some sympathies with the wooden beams and found iron scraps found in Robert Indiana’s sculptures of the late 1950s, an artist with whom Nevelson would later become friends. Along with artists like Richard Stankiewicz and Robert Rauschenberg, Nevelson’s contributions to the 1959 exhibition Sixteen Americans were understood by the New Yorker to show traces of a ‘beat’ aesthetic in American art, whose ‘rag, tag and bob tail materials’ served as a form of ‘protest’ against consumerism.59 Just as this younger generation of artists turned to junk materials in response to urban change and obsolescence, Nevelson’s Black Wall can also be seen as bearing witness to the transformations to the city wrought in the name of modernism.