Iwao Yamawaki

Bauhaus Student (1930–2)

Tate

Introduction

Perspective in art usually refers to the representation of three-dimensional objects or spaces in two dimensional artworks. Artists use perspective techniques to create a realistic impression of depth, 'play with' perspective to present dramatic or disorientating images.

Perspective can also mean a point of view – the position from which an individual or group of people see and respond to, the world around them. You might, for example, hear people saying 'from my perspective' or referring to the point of view of a particular group or set of beliefs: 'the youth perspective' or 'the feminist perspective'.

Make Space! ... the Basics

John Wonnacott

The Norwich School of Art (1982–4)

Tate

What is perspective and how does it work?

Have you noticed that things look bigger if they are close to you and smaller if they are further away? This is perspective. It is perspective that helps make things look three dimensional – and creates a sense of space receding into the distance. There are two types of persepective: linear perspective, and aerial perspective (sometimes also called atmospheric perspective).

Linear perspective

If you look along a straight road or a railway track, the edges of the road or tracks look as if they are coming together in the distance. This is called linear perspective. With linear perspective parallel lines move together as they recede away from you. The point at which the lines appear to meet is called the vanishing point.

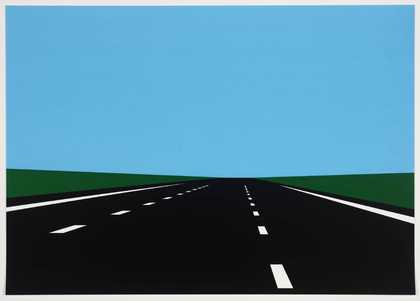

Julian Opie

Imagine you are driving (1998–9)

Tate

To create the impression of a road heading away into the distance, artist Julian Opie has placed a single vanishing point more or less at the centre of the image. The edges of the road meet at this point and suggest a sense of receding space. (Perspective that uses a single vanishing point like this, is sometimes referred to as 'one-point perspective').

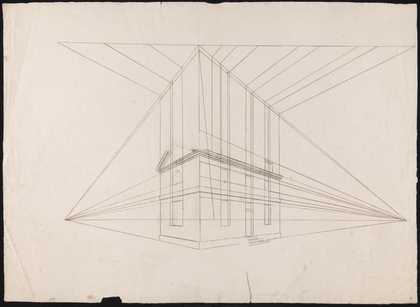

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Tracing of a Perspective Construction of a House (c.1810)

Tate

To represent three-dimensional objects or buildings, artists often use two (or more) vanishing points. Have a look at this sketch by J.M.W. Turner. He has placed a vanishing point at either side of the paper and then drawn the top and bottom lines of the two walls of the building so they meet at these points. The walls look as if they are going back into the distance, which makes the building look three-dimensional.

Artist Ed Ruscha has used two vanishing points (or two-point perspective) in his dramatic drawing of a petrol station. One of the vanishing points is at the bottom right hand corner of the work. The other is off the paper to the left. Can you work out where the vanishing point would have to be for the lines of the front wall and roof of the petrol station to meet there?

Edward Ruscha

Standard Study # 3 (1963)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Aerial or atmospheric perspective

As well as using lines to create the impression of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface, there are other techniques artists use. Aerial perspective or atmospheric perspective refers to the effect that the atmosphere has on the appearance of things when they are looked at from a distance.

William Ratcliffe

Hampstead Garden Suburb from Willifield Way (c.1914)

Tate

If you look at a view from a high building or the top of a hill, buildings, trees, hills and other landscape or city features look blurred or hazy in the distance. The further something is away from you, the less clear its details are and there is less tonal contrast (the contrast between lights and darks). Colours also become less bright the further they are away and blend more into the background colour of the atmosphere – which is blue (unless there is a sunset, when it is red!).

In William Ratcliffe's painting of a suburban street, the houses and gardens in the foreground are detailed and brightly coloured. But the hills, buildings, and trees in the distance are painted in shades of faded blue and purple and it is hard to make out their shapes and details.

Carol Rhodes

Ridge (1999)

Tate

Artist Carol Rhodes uses aerial perspective in her paintings of landscapes – which look as if they have lierally been painted from an aeroplane! Ridge 1999 shows a view from above of a vast empty landscape. At first glance it looks like an abstract composition. But we can make out a few details that suggest it is a landscape – the ridge, what looks like a road, and perhaps an airport landing strip. As the landscape stretches into the distance however the features become so indistinct in the atmospheric haze that they are impossible to identify.

Make an Impact!

Once you know how perspective works, you can start messing with it: add a sense of drama (or otherworldly weirdness) to a landscape or cityscape, or explore abstract space.

Dramatic buildings and spaces

Anthony Hernandez's Rome #17 1999 is a photograph of the interior of a building. The space is ambiguous – it looks like a lift shaft in a building that is under construction – but we can't tell if we are looking up or down it. By centralising the vanishing point of the shaft on the paper, so that the image is symmetrical, he creates a dramatic sense of receding space. We seem to be sucked into the image.

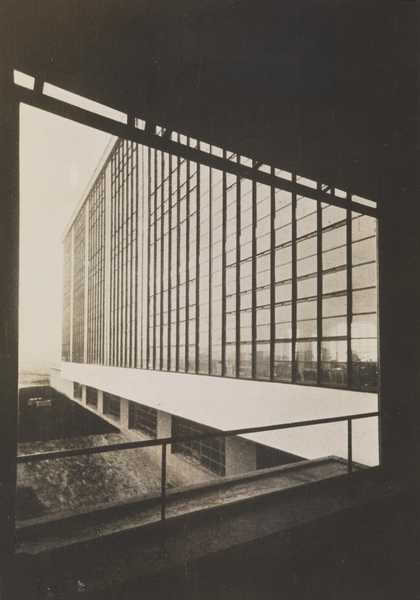

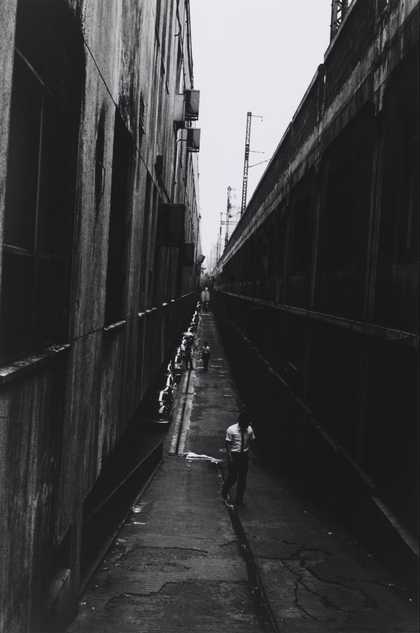

The viewpoints chosen by the artists for these photographs also make use of perspective to emphasise and dramatise the structure of the buildings.

Lucia Moholy

Bauhaus Building, Dessau, view from the vestibule window looking toward the workshop wing (1926)

Tate

Catherine Yass

Bankside: Cherrypicker (2000)

Tate

Yutaka Takanashi

Tokyo-jin (1974, printed 2012)

Tate

Surreal landscapes and cityscapes

Surrealist artists used linear perspective to create strange cityscapes with sharp angled buildings and empty receding streets.

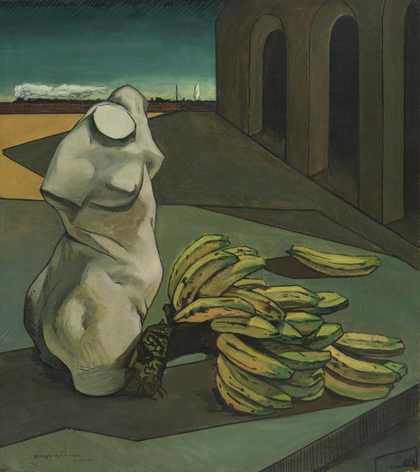

Giorgio de Chirico

The Uncertainty of the Poet (1913)

Tate

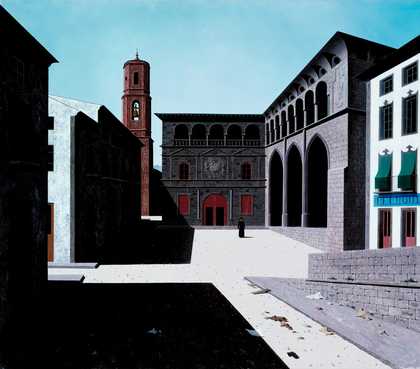

Tristram Hillier

Alcañiz (1961)

Tate

© Estate of Tristram Hillier. All Rights Reserved 2020 / Bridgeman Images

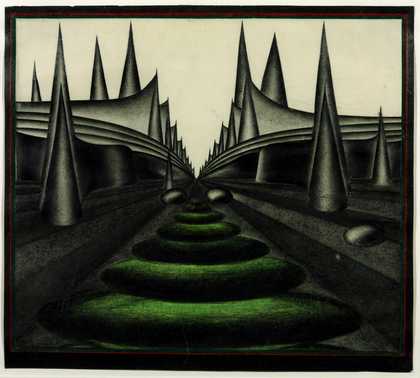

The shadowy receding arcade in Giorgio de Chirico's The Uncertainty of the Poet 1913 adds an eerie backdrop for his odd (and very surreal) foreground still life. Tristram Hillier makes use of perspective to create an equally eerie urban scene of squares, shadows and buildings. The line of trees in Pauls Nash's ghostly landscape painting Pillar and Moon 1932-42, recede to a vanishing point off to the right of the image. By using a vanishing point at the centre of the image, Colin Self draws us into his nightmarish looking garden.

Paul Nash

Pillar and Moon (1932–42)

Tate

Colin Self

Gardens with Green Garden Sculpture (1966–9)

Tate

Artists Yves Tanguy and John Armstrong used aerial perspective in their surreal landscapes. The landscape in Tanguy's Azure Day 1937, the setting for groups of anthropomorphic figures and buildings, seems to go on indefinitely as it fades out to an indistinct haziness. Armstrong exaggerates the contrast between sharp, in-focus, foreground; and blue, indistinct background to create the dreamlike atmosphere of his painting.

Yves Tanguy

Azure Day (1937)

Tate

Perspective and abstraction

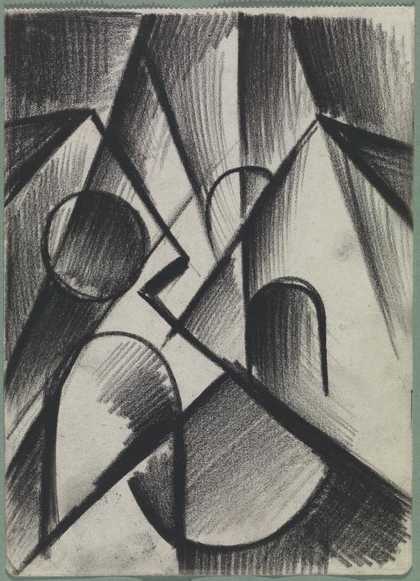

The main idea behind cubism was to represent three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional canvas by bringing together different views of the objects. This often leads to a disorientating sense of perspective. Instead of receding into space objects seem flattened out – or have angles and planes that we don't expect to see.

Juan Gris

The Sunblind (1914)

Tate

Kurt Schwitters

Z 105 Portals of Houses (1918)

Tate

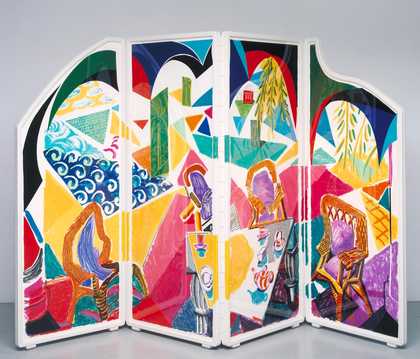

Inspired by cubist space, David Hockney messed with realistic perspective, creating abstracted depictions of his studio.

David Hockney

Pembroke Studio Interior (1984)

Tate

Hedda Sterne's NY, NY No. X 1948 is a response to the New York City, where she moved to in 1941. The semi-abstract mass of lines and planes that appear to depict rooftops, walls, fences, ladders, fire escapes, towers, wood panels and other constructions, suggest her excitement. You get a sense that she is taking everything in at once and pouring out her impressions onto the canvas. Her clever use of different vanishing points in the painting adds to the look of a chaotic built-up environment and hustle and bustle feel of a big city.

Hedda Sterne

NY, NY No. X (1948)

Tate

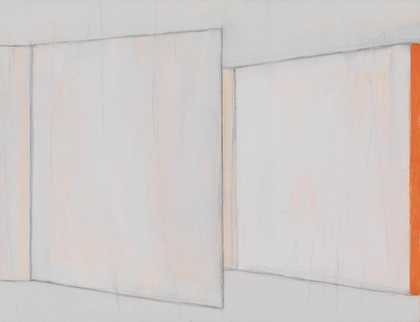

In contrast to Hedda Sterne's complicated and confusing layers of shapes and perspectives, Vicken Parsons creates spaces that appear simple, but are in fact equally confusing. The largely monochromatic paintings show what appear to be spaces or rooms. He uses persepctive to create a sense of three dimensional depth, but the perspectives shift and challenge what we think we are seeing. The paintings simultaneously invite, but also occasionally prevent, us from imaginatively exploring the rooms. Although the rooms seem empty, presence is suggested through the use of light and shadow, giving the paintings an atmosphere of mystery.

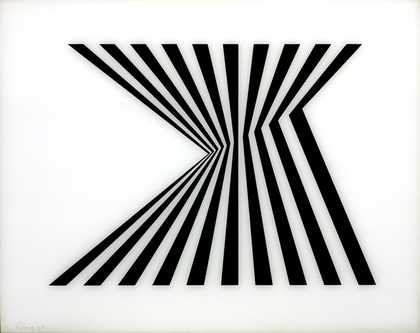

Op artist Bridget Riley often plays with perspective in her abstract paintings and prints that explore optical effects. The three-dimensional ridges of Blaze 1964 recede in a mesmerising spiral. While in Untitled [Fragment 1/7] 1965 she manipulates linear perspective to create this three-dimensional abstract shape.

Bridget Riley

Untitled [Fragment 1/7] (1965)

Tate

Explore more examples of artworks that manipulate perspective to create complex layered, or disorientating images:

Perspective, ideas and meaning

Thomas Struth also made use of perspective in his photographs of urban scenes. But rather than emphasing the drama of architecture, he used perspective to highlight the ordinary. In 1991, two years after the unification of East and West Berlin, Struth began working on a series of photographs of streets in cities in the former East Germany. The cities had previously been inaccessible from the West. All the photographs are taken from a similar viewpoint: he places the camera in the centre of the road at eye level, creating a one-point perspective that leads the viewer's eye along the streets. The slightly shabby East German world that Struth depicts is one in which time is presented as having stood still.

Thomas Struth

Ferdinand-von-Schill-Strasse, Dessau 1991 (1991)

Tate

Thomas Struth

Schlosstrasse, Wittenberg 1991 (1991)

Tate

By using the same approach for all the images, Struth's photographs appear like a scientific record. He doesn't fcous on an interesting bit of the street, or select a dramatic angle – and he gives no hints as to how we should look at the photographs or interpret them. The viewer is left to linger over what might otherwise seem an un-noteworthy, everyday scene. Struth has said about his approach to his photographs that he wants to 'give pause'.

In this artwork by Carey Young, two rows of industrial buildings (yellow on one side and blue on the other) recede dramatically to a single vanishing point at the centre of the image. The stark perspective and symmetry of the buildings contrast sharply with the curled up figure in the foreground. No one else is around, and the emptiness of the scene is heightened by the large expanse of cloudy sky.

The photograph is part of a series by Carey Young called Body Techniques. In each photograph the artist wears a smart two-piece suit and is pictured alone surrounded by recently completed or half-finished construction projects. The photographs were taken in the United Arab Emirates and draw attention to the rapid growth of cities there, stimulated by private and corporate wealth. As the art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson has commented, these photographs ‘depict the architecture of multinational commerce as depersonalized and dehumanizing, futuristic yet dusty projects of progress perverted’. Carey Young explores how the human figure fits into these stark environments. But, as Young herself has explained: ‘it is ambiguous whether the artist is molding herself to the landscape or exploring ways of resisting it.’

Sir Don McCullin CBE

The Battlefields of the Somme, France (2000)

Tate

Thomas Struth and Carey Young use perspective to explore an idea. Photographer Don McCullin uses perspective to help visualise the horrors of war. A long road disappears into the distance across acres of flat fields. The photograph records the location of some of the bloodiest battles of the First World War – the Somme. McCullin's choice of viewpoint, focusing on the road rather than battlefields, is a poingnant reminder of the miserable march that so many young soldiers took to their deaths. He chooses a viewpoint looking down the road – making the road seem endless. The perspective exaggerates the huge scale of the battlefields and the suffering and loss of life that happened there.

Perspectives and Voices

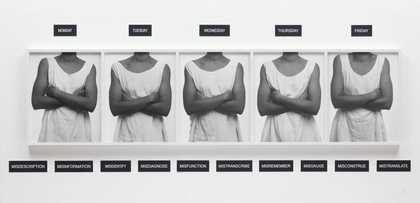

Lorna Simpson

Five Day Forecast (1991)

Tate

So far this resource has explored how perspective techniques are used by artists to create the impression of three-dimensional space, and the various ways artists use (and misuse) it to add drama or meaning to an image or create disorientating abstract artworks.

Perspective in art can also be explored in relation to the viewpoint of artists and how they use this in making their work. All of us have an individual perspective which affects how we think about and respond to the world around us. Lots of things affect our perspective including our gender, our race, our cultural background, our education and our histories and experiences.

Many artists use art as a tool to explore their experiences and make people aware of their perspective.

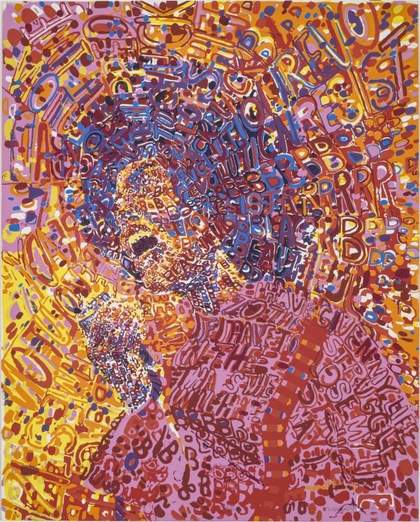

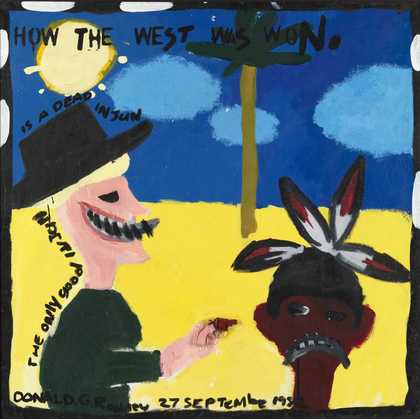

Donald Rodney

In the House of My Father (1996–7)

Tate

Donald Rodney

How the West was Won (1982)

Tate

Artist Donald Rodney explored issues of race and representation from his perspective as young black British artist. He was a leading figure in Britain's BLK Art Group in the 1980s and is recognised as 'one of the most innovative and versatile artists of his generation'. Rodney suffered from the inherited incurable disease sickle cell anaemia and his experiences of being ill and in pain is also something he deals with in his art.

Take a look through Donal Rodney's sketchbooks and find out more about how he used art to explore and put across his experiences and perspectives.

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

Sonia Boyce’s artwork From Tarzan to Rambo ... explores the representation of black people in the media from her perspective which she describes as an 'English born Native'.

The artwork developed from her exploration of the relationship between her own 'self-image' and the one offered by a predominantly white society through the mass media (newspapers, films, TV etc). Find out more about Boyce's ideas in this Look Closer resource.

Cindy Sherman

Untitled #97 (1982)

Tate

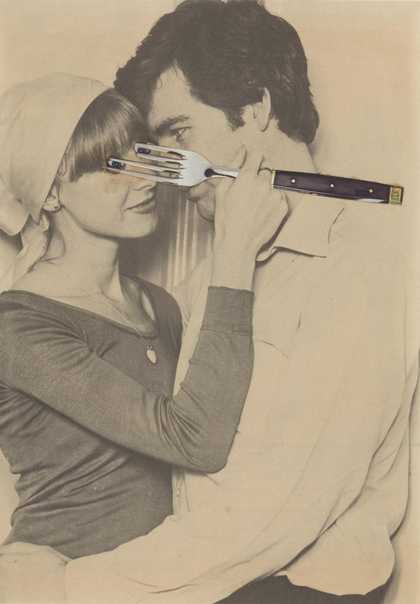

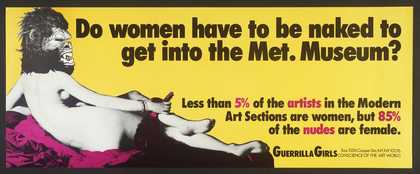

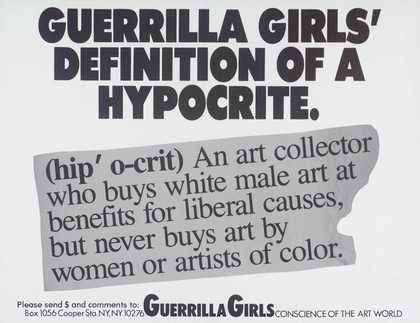

Artists such as Lorna Simpson, Cindy Sherman, Linder and the Guerilla Girls make art from their perspective as feminists. They use art to explore their gender-related experiences within society with the aim of exposing embedded inequalities and showing alternatives to dominant gender roles.

Guerrilla Girls

Guerrilla Girls’ Definition Of Hypocrite (1990)

Tate

The Guerrilla Girls formed in 1984 in reaction to an exhibition called An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture at MoMA (The Museum of Modern Art) in New York. Although the exhibition was supposed to represent the top artists in the world, out of the 169 artists shown only 13 were women. The Guerilla Girls aim to expose sexism and racism in the art world. They make hard-hitting (and often witty) posters, place adverts in newspapers and use direct actions such as demonstrating outside museums, to put across their message.

Find out more about feminist art, the BLK Arts Movement and other groups and movements formed to represent the perspectives of marginalised groups in the art world: