Simeon Solomon

Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene (1864)

Tate

The relationships we share with one another can shape our lives, our work and even history itself. Here are five important queer relationships which influenced the canon of art.

1. Sappho

Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene is a touching image of female love. The piece is inspired by fragmented poems written by a woman named Sappho in the 4th century BC, in which she pleads that Aphrodite help her in her same-sex relationship. The term ‘lesbian’ derives directly from this poet, as her homeland was the Greek Island of Lesbos. Sappho’s story points to a longer history of same-sex desire. It’s perhaps for this reason that Simeon Solomon, a man who was attracted to men in defiance of the law, painted her. While a depiction of two men kissing would have been completely taboo, this is a passionate depiction of same-sex desire.

Solomon’s own sexual preferences eventually lead to his incarceration. When he was released from prison he was rejected by many of his aquaintances, struggled to find work and soon became homeless; a painful reminder of our repressive past.

2. Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell

Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell

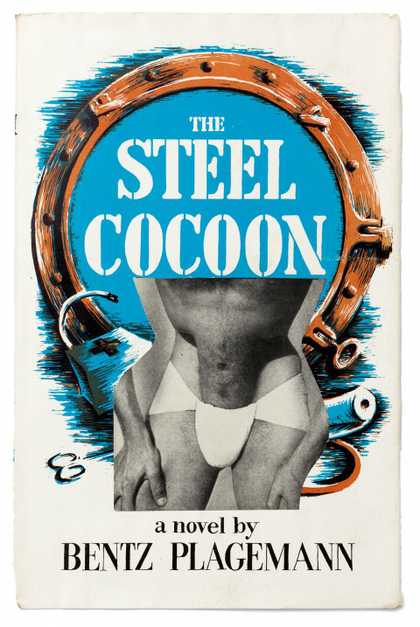

The Steel Cocoon

Islington Local History Centre

Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell

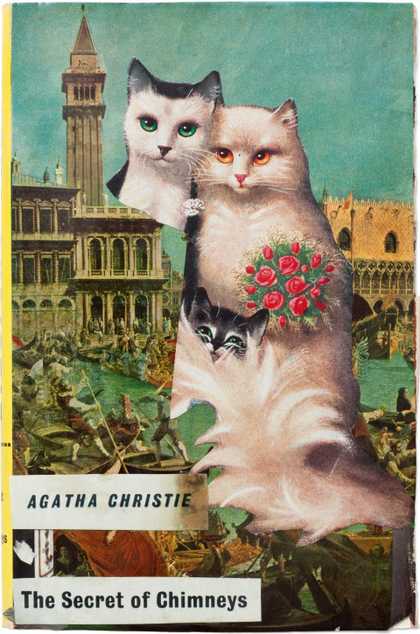

The Secret Chimneys by Agatha Christie

Islington Local History Centre

Playwrights and artists Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell shared a relationship which would go on for sixteen years from the day they met in 1951. Spanning a time when homosexuality was still illegal, they shared a small, 15ft squared, bedsit in Islington and were inseparably close. Nevertheless, until the publication of Orton’s diaries many of his friends and family were unaware that Halliwell was his lover.

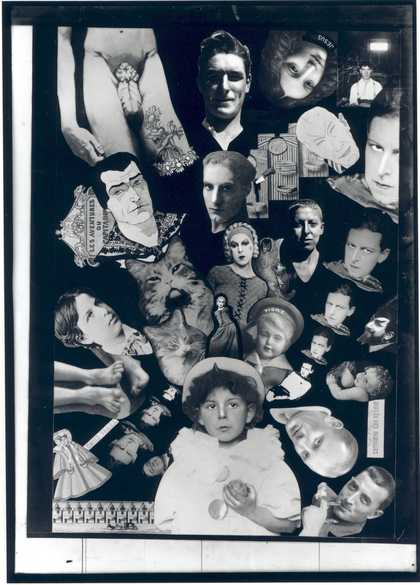

The duo challenged each other artistically, with Halliwell’s editorial eye for detail having a positive impact on Orton’s writing, while Orton’s flair for comedy permeated their work. An outlet for their shared creativity was a passion for collage, which made it’s way onto the walls of their apartment and even into the books of their local library. From 1959 – 1962 the pair stole and defaced hundreds of books, smuggling them back into the building for unwitting librarians and visitors to find. This was a lighthearted prank, which, despite having political undertones, was harmless and only mildly offensive. Yet, upon the discovery of their involvement, they were put in jail for six months.

Many believe that their imprisonment for ‘malicious damage’ to the books was merely a cover for the real cause of their punishment, the fact that they were queer. Orton’s friend, the actor Kenneth William’s explains Orton’s feelings on this topic:

I know from all my conversations with him that [Joe] deplored what he regarded as, the hypocritical nature of the established English view of homosexuality … and maintained that they would turn a blind eye to all kinds of situations if it suited them. He thought that was evil

Kenneth Williams, A Genius Like Us: A Portrait of Joe Orton, 1982

Orton used this experience to his advantage, finding the inspiration in this injustice to create the plays that would make him famous. Halliwell, on the other hand, suffered from delicate mental health becoming increasingly alcoholic and jealous of Orton’s success. In 1967 Halliwell murdered his lover and killed himself.

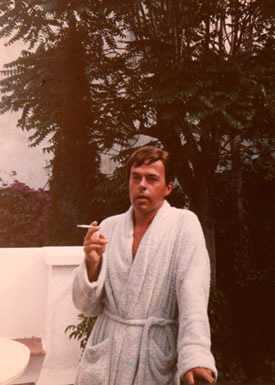

Kenneth pictured on holiday in Tangier

The Orton Estate

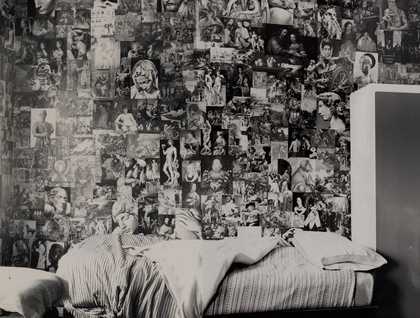

Interior of the flat at 25 Noel Rd showing the extent of the collages

Image courtesy of Islington Council

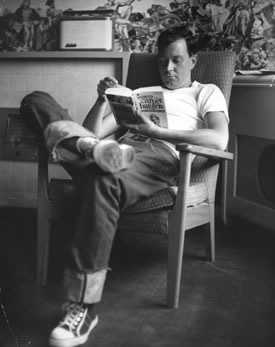

Joe in the flat at 25 Noel Rd in 1964

Courtesy The Leicester Mercury

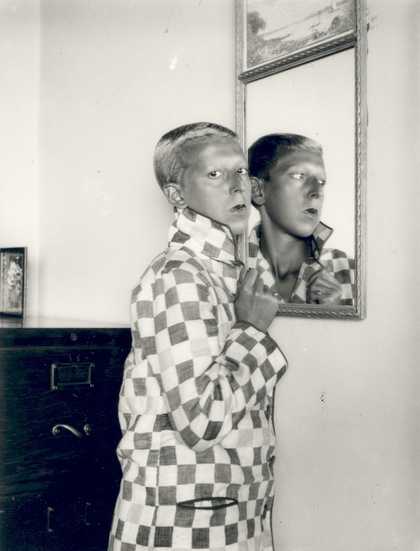

3. Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

Claude Cahun Aveux non avenus. Illustré d’hélio-gravures composées par Moore d’après les projets de la’auteur. Préface de Pierre Mac Orlan, courtesy of the British Library

Born as Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob, this fascinating artist tried a few different names before settling on Claude Cahun. Her stepsister, partner and collaborator Suzanne Malherbe chose a similarly asexual name, Marcel Moore. Together and individually, the pair created a subversive body of work that has often been associated with surrealism. Their art explored new possibilities for gender, sexuality and personal identity. Cahun used female pronouns, hence our reference to her as female, but in her autobiography Aveux non Avenus she clearly states that ‘neuter is the only gender that always suits me’.

Cahun’s work was highly respected, even within famously misogynistic and homophobic circles of the surrealists, where André Bretonrecognised her as ‘one of the most curious spirits of our time’. Many years later David Bowie continued to sing her praises:

You could call her transgressive or you could call her a crossdressing Man Ray with surrealist tendencies. I find this work really quite mad, in the nicest way … she has not had the kind of recognition that, as a founding follower, friend and worker of the original surrealist movement, she surely deserves

David Bowie, Tonight’s High Line - David Bowie Recommends … , 2007

Perhaps one of the most inspiring things about Cahun was her constant and fearless subversion of ‘normality.’ She rejected all possible categorisation as either a woman, lesbian, artist or writer. Her portrait series are particular reminder of this as she transmutes from one version of herself to another. When the Nazis arrived in Jersey, Cahun and Moore began using their art as a means to undermine the enemy. They disguised themselves at military events and slipped anti-German flyers into the pockets of the men. This lead to their eventual incarceration, which played a fatal toll on Cahun’s health, leading to her death and Moore’s subsequent suicide.

Claude Cahun self portrait c.1927 courtesy Jersey Heritage collections

Claude Cahun self portrait c.1928 courtesy Jersey Heritage collections

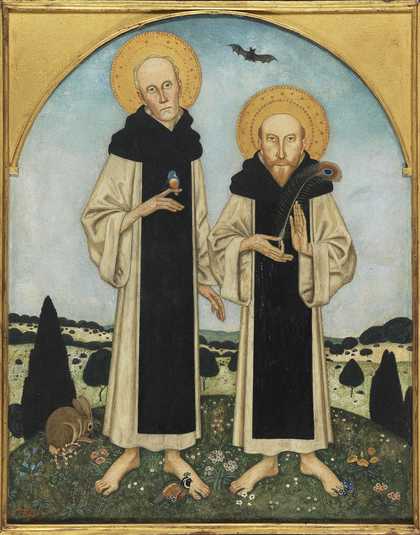

4. CHARLES RICKETTS AND CHARLES SHANNON

Edmund Dulac 1822–1953

Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon as Medieval Saints 1920

387 x 305 mm

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Ricketts and Shannon lived together for most of their lives and shared a deeply committed relationship, although the exact nature of that relationship remains a mystery. It was once reported that Ricketts asked a friend to leave their house after being asked too many questions on the subject. As the friend walked away he exclaimed: ‘But you are, aren’t you? You do, don’t you?’, to which Ricketts made no reply.

As well as pursuing individually successful careers, the duo also established an art magazine, The Dial, founded the Vale Press and formed a renowned art collection. Together they designed and illustrated the majority of Oscar Wilde’s books, forming a lasting friendship with the writer.

To Wilde their home was ‘the one place in London where you will never be bored, and where you will not be asked to explain things’. The latter comment is a nod to the safe havens they created; homes which they renovated, decorated and filled with beautiful objects. These shared spaces became hubs for creative visitors, including the poets William Yeats and Bernard Shaw.

In 1929 Shannon fell from a ladder and became brain damaged. He was cared for by Ricketts, who was devastated but lovingly patient:

I realise that, viewed as a whole, this trial is small compared to the forty years of perfect companionship I have enjoyed

Charles Ricketts quoted in Matt Cook, Queer Domesticities, 2014, p. 52

Ricketts died two years later and Shannon soon afterwards. Their close friend, Edmund Dulac, immortalised their relationship in this portrait where they appear as two monks, hinting at the all-male bond they shared. Other artists have also painted their portrait, perhaps being touched by Ricketts and Shannon’s loving devotion.

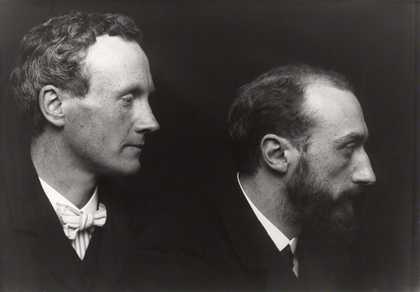

George Charles Beresford

Charles Haslewood Shannon; Charles de Sousy Ricketts 1903

National Portrait Gallery

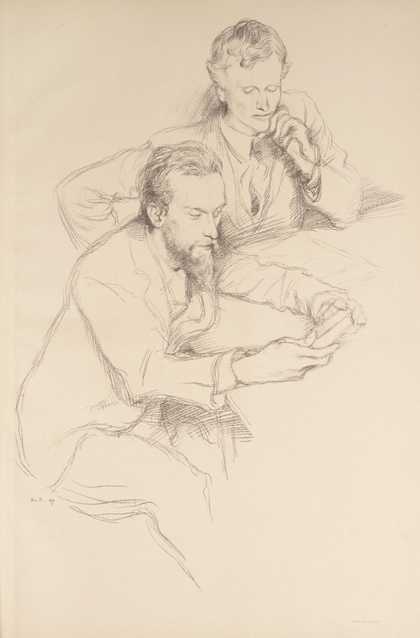

Sir William Rothenstein

Mr Charles Ricketts and Mr Charles Hazelwood Shannon [Part IX] (1897)

Tate

Jacques-Emile Blanche

Portraits of Charles Shannon and Charles Ricketts 1904

Tate

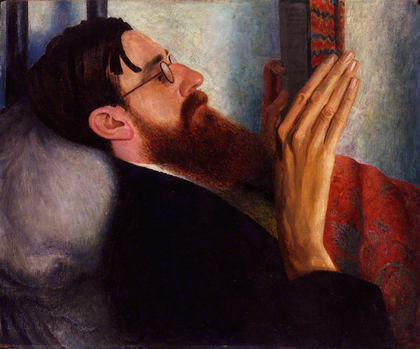

5. Dora Carrington

Dora Carrington

Lytton Strachey 1916

National Portrait Gallery

Lytton Strachey; Dora Carrington

by Unknown photographer

vintage snapshot print, 1920s

NPG Ax24020

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Dora Carrington was an experienced painter, but also created beautiful decorative pottery, murals, book designs, fireplace tiles, inn signs and quilts, as well as making several films. Her passion for trying new mediums and experiences is summarised nicely here:

Carrington is like some strange wild beast – greedy of life and of tasting all the different ‘worms’

Ottoline Morrell, quoted in Gerzina, 1995

She began her career at The Slade School of Art in 1910, exposing her to the Bloomsbury group, who lived and worked in the area. It was here that she met their founder, the openly gay Lytton Strachey. The pair formed an intimate relationship, becoming deaply enmeshed in each other’s lives. Even after Carrington married Ralph Partridge, Strachey lived with them and accompanied them on their honeymoon. In 1932 Strachey died from cancer and Carrington committed suicide two months later.

Although Carrington married Partridge and loved Strachey, she described her sexuality as ‘hybrid’. This, coupled with her cropped hair and boyish looks, set her apart from traditional female archetypes.

Carrington is interesting as a modern heroine precisely because she didn’t fit into conventional roles – or rather she fitted in a misfit kind of way

Teresa Grimes, Judith Collins, Oriana Baddeley, Five Women Painters, 1989

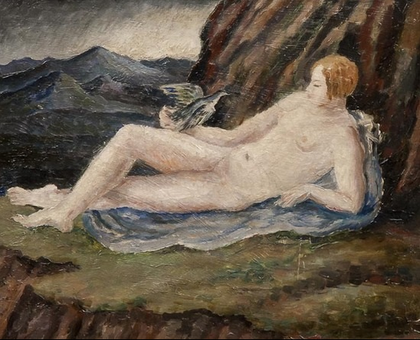

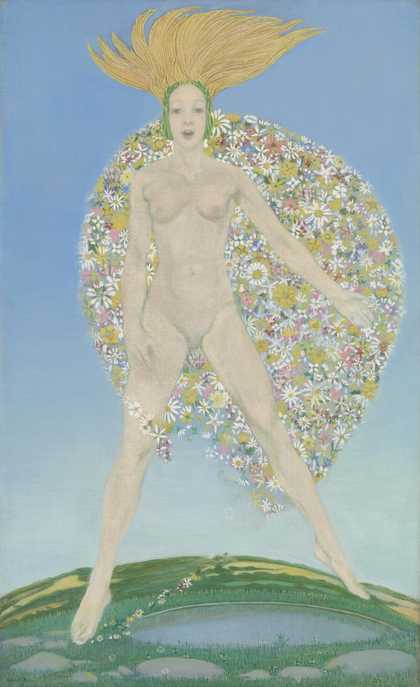

Carrington’s most famous female lover was Henrietta Bingham, the sitter for Reclining Nude with Dove in a Mountainous Landscape. When they met Carrington wrote to Strachey about a woman with the ‘face of a Giotto Madonna’, who ‘made such wonderful cocktails that I became completely drunk and almost made love to her in public’ (quoted in Emily Bingham, Irrepressible: The Jazz Age Life of Henrietta Bingham, 2015). Within the context of this painting, Female Figure Lying on her Back 1912 takes on an undertone of lesbian desire, emphasised by the fact that it was still deemed inappropriate by many for women to draw nudes from life. The Slade did not abide by this rule, however women still had to take their classes separately from men. Each of these paintings hold a strong emotional power, hinting at the unconventional loves held by this remarkably unconventional woman.