Frank Huddlestone Potter

Girl Resting at a Piano ()

Tate

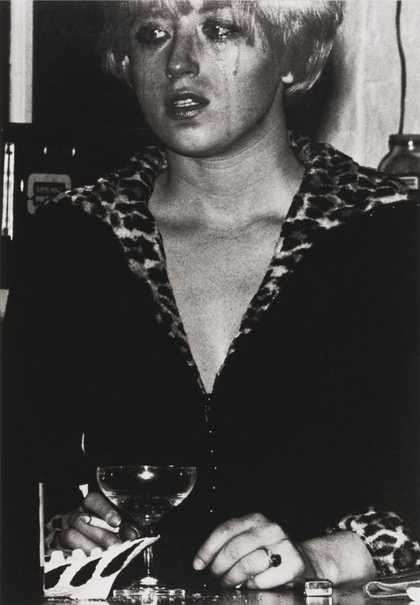

Frances Stark

Behold Man! (2013)

Tate

Sam Taylor-Johnson OBE

Killing Time (1994)

Tate

Harold Gilman

Lady on a Sofa (c.1910)

Tate

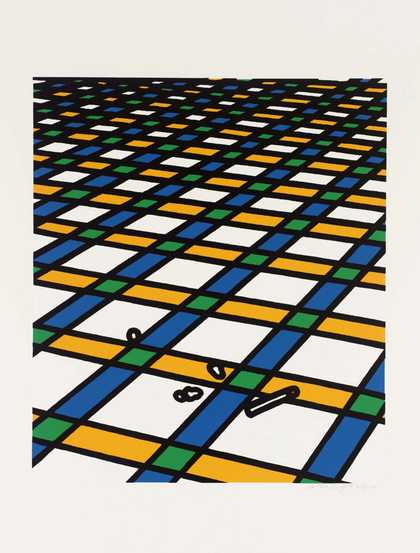

Patrick Caulfield

18. ‘And I am alone in my house’ (1973)

Tate

© The estate of Patrick Caulfield. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2026

Boredom, ennui and the domestic

Stuck at home without our normal social interactions, we have all probably felt bored or plain sick of it. Artists have often looked at that feeling of boredom or ‘ennui’ (the French term for feeling bored and low and listless).

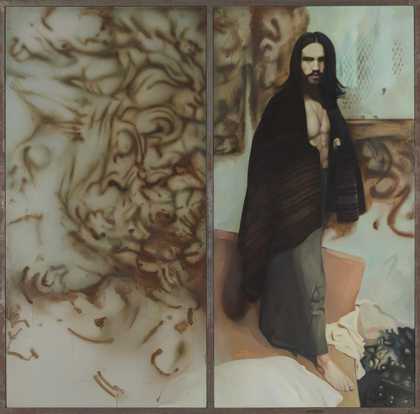

Making art in isolation

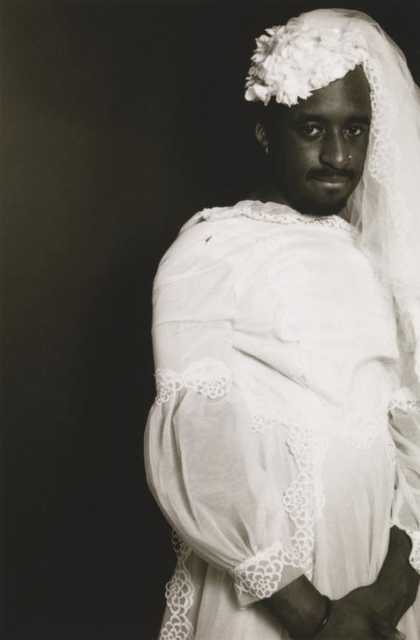

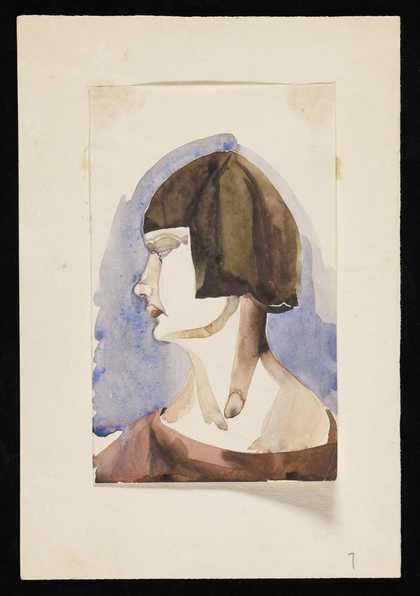

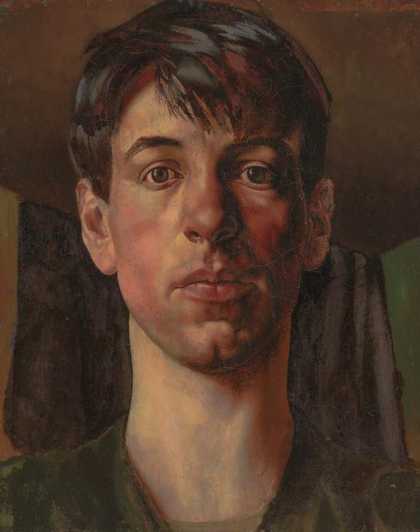

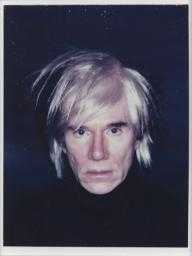

But reducing our interactions means that we can focus quite deeply on one single thing. Taking yourself as a subject – such as making a self-portrait – can give artists a chance to delve into their own image, and what lies beneath. British artist Jean Cooke said:

‘Sometimes I paint self-portraits to show off, sometimes to hide away in solitude, sometimes to say “‘Here I am”’, sometimes to say “‘I want to be alone”’. But always there is a searching for the unknown, the previously unperceived.’

What might a self portrait reveal about you?

Ajamu

Self-portrait in Wedding Dress 1 (1993)

Tate

Ithell Colquhoun

Watercolour self-portrait ([c.1927–30])

Tate Archive

Sir Stanley Spencer

Self-Portrait (1914)

Tate

Ronald Ossory Dunlop

Myself with Cadger’s Pipe (1950)

Tate

Dame Ethel Walker

Self-Portrait (?exhibited 1930)

Tate

Andy Warhol

Self-Portrait with Fright Wig (1986)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© 2026 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

Sometimes, it’s less about revealing something, and more about seeing your own face or body as the easiest model to bring your ideas to life.

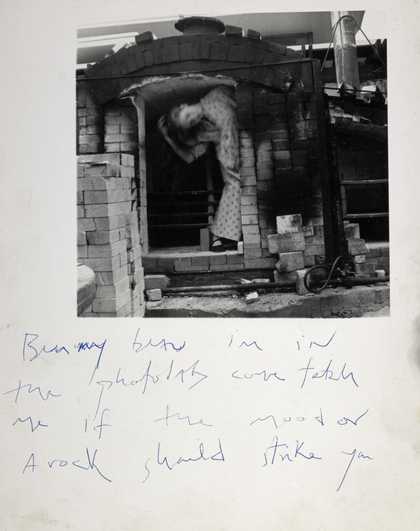

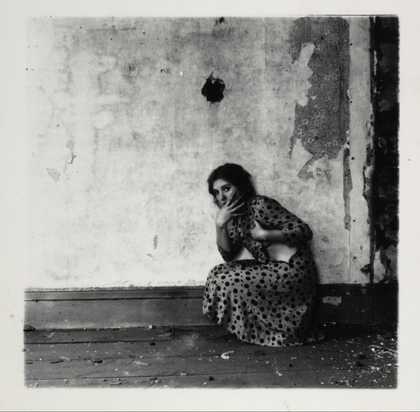

Francesca Woodman often used herself in her photographs. When her roommate and close friend Sloan Rankin asked why, Woodman replied: ‘It’s a matter of convenience, I’m always available’.

Francesca Woodman

Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island (1975–8)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© Woodman Family Foundation / Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

Francesca Woodman

Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island (1975–8)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© Woodman Family Foundation / Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

Francesca Woodman

Untitled, from Polka Dots Series, Providence, Rhode Island (1976)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© Woodman Family Foundation / Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

And it doesn’t have to be people. Artists also return to the same subjects over and over again. What can you find out by looking at one specific subject over and over again?

One of the most famous British artists of the last 200 years, John Constable, studied the clouds, making quick painted sketches outdoors (often called ‘en plein air’ from the French). He worked from these outdoor studies using the knowledge he gained of the world outside in his large landscape paintings

John Constable

Cloud Study (1822)

Tate

Creating in isolation because of illness can also be an unstoppable urge. Adrian Stokes painted eleven still lifes during his final weeks from early September 1972, after being diagnosed with terminal cancer, and his death on 15 December. The objects in this series, known as ‘The last eleven’, are objects he'd painted many many times before: glass decanters, wine bottles and pots made by his wife. He returned to these items and motifs over and over again, despite his weakening health. The process of creating can sometimes be as important as the subject.

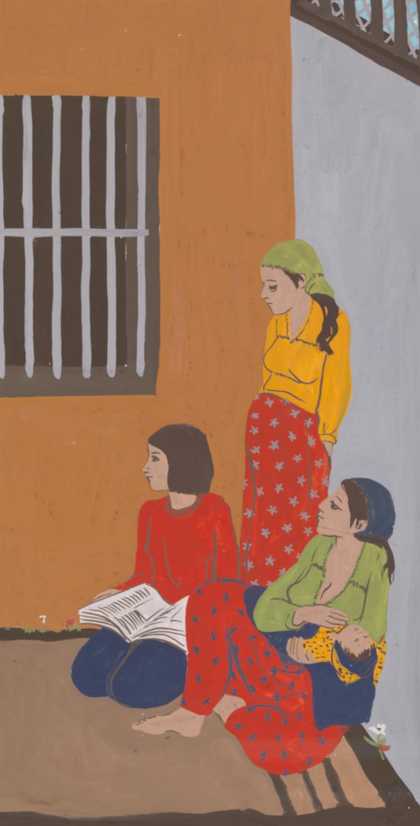

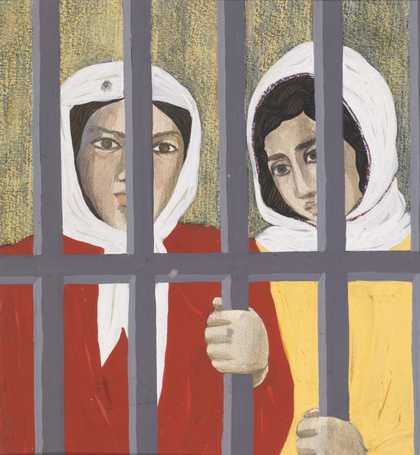

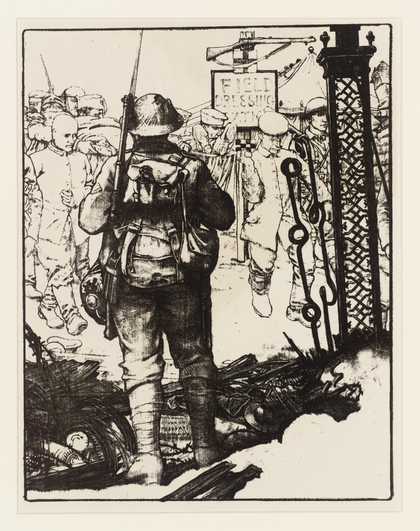

Isolation as punishment

Isolation can be used as a punishment. The most obvious example of this is sending people to prison, where they are isolated from society.

Turkish artist Gülsün Karamustafa was imprisoned in Turkey for six months in the early 1970s for her political activism. Between 1972 and 1978 she painted a series of works reflecting on this time showing women of all ages in prison settings.

Isolation within prison walls has been a recurring theme for artists throughout the years.

Isolation within the city

Isolation doesn't always mean you aren't seeing a lot of people though. Humans can feel isolated even amongst huge numbers of people. Many artists have explored the isolation or feeling of loneliness that can come from being one person within a city.

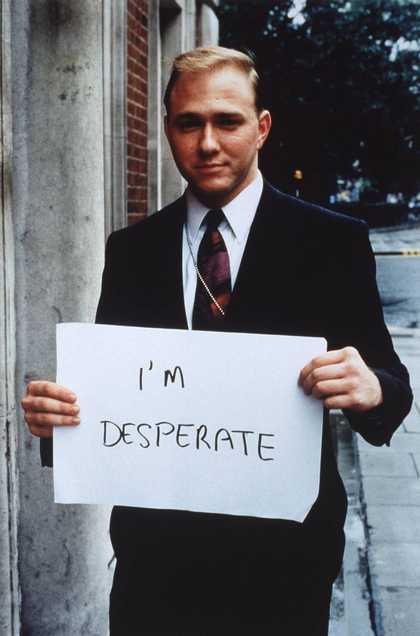

Gillian Wearing CBE

‘I’m desperate’ (1992–3)

Tate

© Gillian Wearing, courtesy Maureen Paley/ Interim Art, London

This is one of Gillian Wearing’s best known images, from a series she made in 1992-3 called Signs that Say What You Want Them To Say and Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say Wearing stopped passers-by in a busy area of South London, and asked them to write down what was on their mind. With their permission, she then photographed them holding their statement. This photograph shows a smartly-dressed young man with a mild (even slightly smiling) expression holding a sign saying simply, ‘I’m desperate’.

In a 1996 interview Wearing said: ‘People are still surprised that someone in a suit could actually admit to anything… I think he was actually shocked by what he had written, which suggests it must have been true. Then he got a bit angry, handed back the piece of paper, and stormed off.’ (Unpublished interview with Marcus Spinelli, South Bank Centre 1997.)

There are around fifty images in this series. Artist and writer Scottee has spoken about how seeing working class people given voice in the gallery is important. Do you feel isolated or welcomed in a space when you see people who are (or aren’t) like you shown on the walls?

Carey Young’s Body Techniques series, made in 2007, is a series of eight photographs. Each image shows the artist wearing a smart two-piece suit and presented alone in the centre of a landscape of empty and yet-to-be-finished construction projects in the cities of Dubai and Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates.

Young made the series during a residency at the Sharjah Biennial Artist in Residence Programme. It draws attention to the rapid growth of cities in the UAE, and the private and corporate wealth that represents. Since there is no other human life in the pictures, you can see it as a dystopian comment on global capitalism. (Dystopia means a society that is unjust or there is a lot of suffering. It’s often used to describe visions of the future in science fiction which present a future we hope will never come about.)

Isolation or solitude?

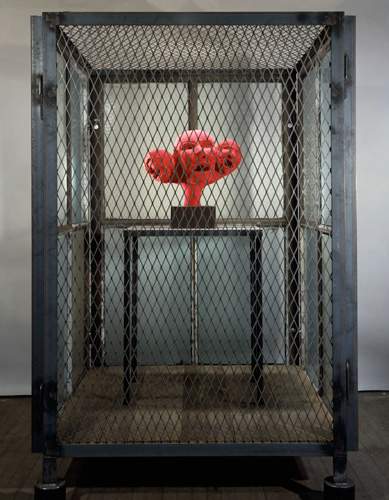

‘Solitude, even prolonged solitude, can only be of very great benefit.’

Louise Bourgeois

Isolation might not always be a bad thing for an artist.

Figures are often isolated in Bourgeois’ work, and she thinks of both the isolation she felt as child and as a mother.

ARTIST ROOMSTate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

© The Easton Foundation, photo Christopher Burke

Louise Bourgeois

Single II (1996)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

Louise Bourgeois

Empty Nest (1994)

Tate

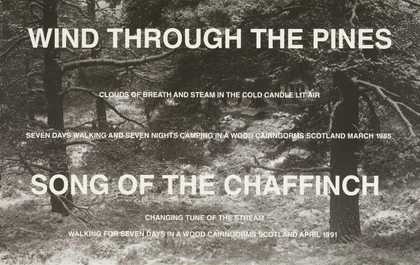

And maybe solitude in nature, such as walking alone, can actually be a way to connect with the natural world, without the hum of humanity getting in the way.

Hamish Fulton

Wind through the Pines (1985, 1991)

Tate

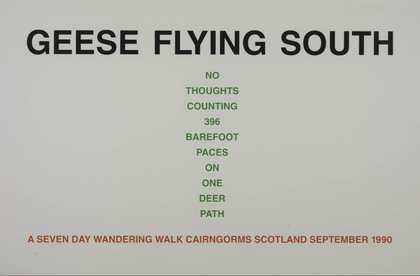

Hamish Fulton

Geese Flying South (1990)

Tate

Hamish Fulton

Song Path (1992, 1993)

Tate

Isolated moment

Isolated can also mean something that you take out of context, out of its environment, capturing one small part of it. John Latham was interested in the possibilities of representing time and our experience of time. Time is infinite, but we experience it in snatched moments and fragments.

John Latham

Time-Base Roller (1972)

Tate

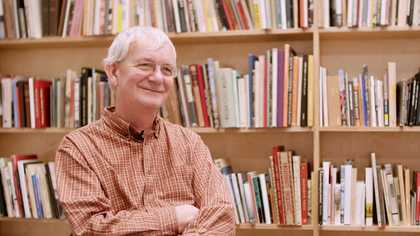

Many photographers have worked capturing ‘snap shots’ or brief moments when the camera was pointed in that direction. Martin Parr’s documentary-style photographs of the New Brighton area of Liverpool in the 1980s give us a window into that time and place.

Martin Parr CBE

The Last Resort 23 (1983–6, printed 2018)

Tate

Martin Parr CBE

The Last Resort 25 (1983–6, printed 2018)

Tate

Martin Parr CBE

The Last Resort 29 (1983–6, printed 2002)

Tate

Martin Parr CBE

The Last Resort 40 (1983–6, printed 2018)

Tate

But now, when so many photographs are taken, shared and seen, do we ever manage to capture an unfiltered isolated moment? Or, as photographers, are we always making our own choices of what to include, and what to leave out? When we isolate an image from what is happening around it, is it still a whole image? Are the images that we think are candid, actually staged?

And is a snapshot ever telling us the whole story?

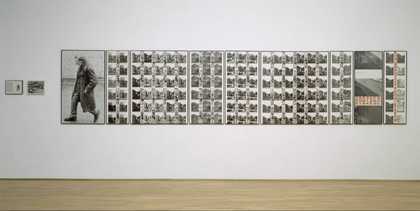

Ian Breakwell began writing a Continuous Diary in 1965. Over the next twenty years, he recorded incidental details of his life.

The Walking Man Diary records an unknown man walking a regular route around the Smithfield area in the City of London, where Breakwell was living at the time, from 1975-8.

I began to take photographs of him if he happened to be passing by when I looked out of the window. All the photographs are taken from the same third floor window vantage point: the view is the same but the time passes. Two adjoining photographs may be separated by seconds, or weeks, or months.

Ian Breakwell

The Walking Man Diary (1975–8)

Tate

In fact the man stopped walking that route in 1977 and Breakwell starting putting together this work once he ‘disappeared’ from Breakwell’s window. When he ‘reappeared’ Breakwell started photographing him again. But have we learnt anything about this man from these years of images of him crossing the road? We know next to nothing about him as a subject. Perhaps this window onto him is more fascinating, as we can project our own ideas onto him.