Turner Bequest CCX 1–66a; 68–89; 93–93a

Sketchbook hardbound in brown calf leather, borders of front and back covers stamped with pattern, spine decorated with raised bands and inscribed with gilt lettering ‘welsh itinerary’

Blue marbled pastedown and endpapers; remains of brass clasp on front and back covers

Signed and inscribed in black ink by Henry Scott Trimmer ‘No 251 | Containing 78 leaves – | Pencil Sketches on | both Sides –’ and Charles Turner on Tate D41237

Signed in pencil by John Prescott Knight ‘JPK’ and Charles Locke Eastlake ‘C.L.E.’ on Tate D41237

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram front cover top left and on Tate D41237 top left towards centre

Stamped in black ‘CCX’ front cover top right and inside front cover pastedown top left

Inscribed in pencil by Andrew Wilton ‘ff 90 – 92 | missing 1973 | f 93 bound | between ff 42, 43 | AW 1973’ on Tate D41237

89 pages of white wove paper

Watermarked ‘Smith & Allnutt | 1822’

Approximate size of page 118 x 75 mm

Blue marbled pastedown and endpapers; remains of brass clasp on front and back covers

Signed and inscribed in black ink by Henry Scott Trimmer ‘No 251 | Containing 78 leaves – | Pencil Sketches on | both Sides –’ and Charles Turner on Tate D41237

Signed in pencil by John Prescott Knight ‘JPK’ and Charles Locke Eastlake ‘C.L.E.’ on Tate D41237

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram front cover top left and on Tate D41237 top left towards centre

Stamped in black ‘CCX’ front cover top right and inside front cover pastedown top left

Inscribed in pencil by Andrew Wilton ‘ff 90 – 92 | missing 1973 | f 93 bound | between ff 42, 43 | AW 1973’ on Tate D41237

89 pages of white wove paper

Watermarked ‘Smith & Allnutt | 1822’

Approximate size of page 118 x 75 mm

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

The Brighton and Arundel sketchbook holds within its eighty-nine leaves drawings of a variety of subjects and was used by Turner in stops and starts during 1824. It was predominantly employed to record views of the Hampshire and Sussex coast and aspects of Yorkshire. There is also written memoranda on developments in the technology of lithography, financial accounts relating to travel expenses and a list of commissioned work for engraving. Two reasonably coherent groups of drawings which represent Turner’s output over two separate tours can be identified: the first, a two or three day visit to Portsmouth, Brighton and Arundel and the second, a tour of the area around Leeds, West Yorkshire, conducted later in the year.

The precise date of the Hampshire and Sussex coast tour is yet to be firmly established, though the artist provided an itinerary of sorts in an inscribed list of expenses incurred whilst travelling from Portsmouth to Arundel and Brighton (Tate D18462; Turner Bequest CCX 85). The art historian Ian Warrell has astutely shown that Turner must have been in Brighton before November 1824 owing to the presence of a waterwheel pictured next to the Chain Pier tollhouse on Brighton Beach (Tate D18365; Turner Bequest CCX 33a).1 The waterwheel was swept away in November as a result of violent storms, providing a secure terminus ante quem for the sketch’s production. Warrell also suggests that Turner could have travelled the Hampshire and Sussex coast before his extensive late summer trip to the continent to study the Meuse and Moselle rivers (which commenced on 10 August 1824). Possible support for this proposal is found in the 3 June edition of the Brighton Gazette where it is reported that a ‘Mr Turner’ was one of the arrivals at the New Steine Hotel.2 Conversely, the artist may have visited Portsmouth, Arundel and Brighton after his continental tour. He returned to England on 15 September and could have made a short sketching trip before November, when he travelled up to Yorkshire to stay at Farnley Hall with his close friend and patron Walter Fawkes.

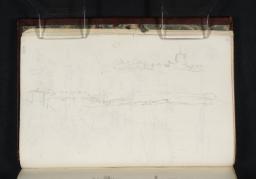

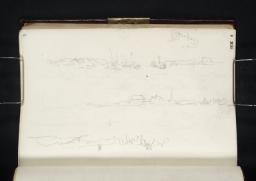

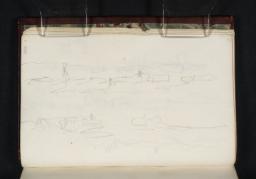

While Portsmouth is relatively unexplored in this book (it is represented in only a few sketches: Tate D41237, D18311–D18312; Turner Bequest CCX 1–1a), Brighton and Arundel are depicted in a large number of drawings. According to his list of expenses Turner appears to have visited Arundel after Portsmouth, finishing his trip at Brighton. A picturesque town set within a steep vale of the Sussex South Downs, Arundel is the ancestral seat of the Dukes of Norfolk. Arundel Castle, surrounded by acres of parkland, dominates the small town and the Arun river valley from atop a medieval motte. Turner sketched Arundel and its Castle extensively (Tate D18418–D18447, D18456–D18461; Turner Bequest CCX 63–77a, 82–84a), developing this material into two designs for William Bernard Cooke’s Rivers of England series (Tate D18139, D18120; Turner Bequest CCVIII F, G, Tate impression T04815) and a design entitled Arundel Castle and Town, Sussex, for Charles Heath’s Picturesque Views in England and Wales published in 1834 (Tate impression T04602).3

Turner’s motivations for visiting Brighton appear to have been the same as for Arundel: to collect sketches to be transformed into engraving designs. Drawings of this fashionable seaside resort were amalgamated and adapted to form Brighthelmstone, a view published in 1825 for the Picturesque Views of the Southern Coast of England series (Tate impression T05289).4 In this print Turner chose to picture Brighton from the sea looking back towards the town, from a vantage point in front of the then newly erected Chain Pier. This structure is depicted often and from different angles in the Brighton and Arundel sketchbook and elsewhere (Tate D18335–D18340, D18343. D18345, D18347–D18348, D18355–D18356, D18361, D18364–D18365, D18367, D18369, D22812, D22821–D22822, D22824, D22895–D22896, D22773, D24836, N01986, N02064, T03886; Turner Bequest CCX 14a–17a, 20, 21, 22–22a, 27–28, 31, 33–33a, 34a, 35a, CCXLV 18, 22a–23, 24, 67a–68, CCXLIV 111, CCLIX 271). Completed in September 1823 at a cost of £30,000, the Pier was constructed to accommodate the growing amount of cross-Channel traffic via Brighton and Dieppe in the years following the end of the Napoleonic Wars.5 Steam-powered packets emerged as the new and improved mode of long-distance water transport, and the Pier provided a more suitable embarkation and disembarkation point for such ferry services than the small boats previously launched from the beach. The Pier was built to the plans of Captain Samuel Brown, who had designed the Union suspension bridge over the Tweed.6 Its deck was over one thousand feet long, supported by chains suspended from four cast-iron towers spaced at intervals on wooden piles driven deep into the seabed.7 Processions and fireworks displays marked the inauguration of Brighton Chain Pier on 25 November 1823, and it proved an immediate success.8 In the following years kiosks were installed in the towers and several other attractions opened on the Pier walkway.

While it is clear that Turner was interested in the visual impact made by the Chain Pier on Brighton’s coastline, his sketches of the structure are also testament to the artist’s keen awareness of contemporary industrial advancements and of the changes transforming his own familiar terrestrial and maritime environments. The new landing stage facilitated swifter movement between land and sea, between Turner’s England and the Continent.

In addition to pictures of the Chain Pier, Turner sketched Brighton’s celebrated Pavilion, the summer pleasure palace of the Prince Regent, and the seafront where works were in progress to construct the developing district of Kemp Town. Erected to the designs of Charles Busby, the new townhouses at Arundel Terrace and Lewes Crescent were recorded by Turner in a series of sketches.9 Also among the Brighton subjects are drawings taken at St Nicholas’ Church where the artist pictured both the chancel and graveyard, which contained tombs of some famous local residents. The grave of Phoebe Hessel, whose biography is inscribed on the headstone, particularly captured Turner’s attention (Tate D18346–D18347; Turner Bequest CCX 21a–22). Hessel, a native of East London’s Stepney, is renowned for serving in the British army for seventeen years disguised as a man, probably to follow her soldier lover Samuel Golding.10 Even after enduring wounds at the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745 Hessel’s true identity remained secret. When Golding died, Hessel moved to Brighton and sold fruit near the Pavilion, existing on a small pension endowed by the Prince Regent. She died at the venerable age of 108. Turner transcribed Hessel’s epitaph in rough notes written around drawings taken from St Nicholas’ Church. Given her remarkable story and intrepid character, it is little wonder that Turner was intrigued to spend time at Phoebe Hessel’s resting place.

The sketches of Brighton complete the body of work produced on this short tour of the Hampshire and Sussex coast. The sketchbook appears not to have been used again until November and December 1824 when Turner visited Yorkshire, staying at Farnley Hall, the estate of his close friend and patron Sir Walter Fawkes.11 This was to be the artist’s last visit to Farnley as Fawkes died tragically a year later in 1825. Whilst walking the grounds of the estate Turner rendered a small group of sunset studies in pencil which this cataloguer proposes are connected to equivalent studies produced in watercolour in the now dispersed Farnley-Munro sketchbook (see Tate D18478; Turner Bequest CCX 93a). 12 There also views of Wharfedale and possibly the town of Leathley, located close to Farnley Hall. Most significant of these Yorkshire sketches are those that depict the town of Kirkstall, near Leeds (Tate D18390–D18391, D18393–D18399, D18409–D18416; Turner Bequest CCX 48–48a, 50–53, 58a–62). Celebrated for its majestic ruined Abbey founded by an order of Cistercian monks in 1152, Kirkstall was also the site of an important lock and incorporated a section of the Leeds to Liverpool Canal as well as the improved Leeds to Bradford turnpike road.13 Turner’s comprehensive studies of Kirkstall Abbey and Lock were transformed into two highly finished designs (Tate D18145, D18146; Turner Bequest CCVIII L, M) which were engraved and published in 1826 as part of Cooke’s Rivers of England (Tate impressions T04811, T04816).

In addition to views of the Hampshire and Sussex coast and of Yorkshire, Turner produced a few sketches in this book that appear to be unconnected to other subjects represented. These depict the mammoth ship Columbus, a four-masted barque which conveyed well over six thousand tons of timber from Quebec to London (Tate D18373–D18374, D18392, D18406–D18408; Turner Bequest CCX 37a–38, 49, 57–58). Launched on 28 July 1824, she was grounded soon after at the Gulf of St Lawrence. The Columbus wrecked upon her arrival at the English Channel and with the help of a fleet of ‘branch pilots, steamboats, warps and the capstan’ she was lugged to a mooring point on Blackwall Reach, East London, on 1 November 1824.14 The Columbus’ huge size (she measured ninety-one metres in length) and ‘boisterous passage’ to England was well documented in the national press. Docked at Blackwall, Londoners like Turner were able to visit and see for themselves this ‘vaunted Colossus of the deep’.15 A journalist for The Mirror writes that she was ‘at length accessible to the investigation of the curious, however timid they may be’ and that by taking a trip to Blackwall ‘lovers of sightseeing may gratify their whim and fantasy without encountering a heavy sea, a fearful ice-shore, or blue-water banyan days’.16

Turner, whose own pub The Ship and Bladebone was located fairly close by at Wapping, maintained throughout his life a love of shipping, depicting vessels moored on the beach, docked in a harbour, or sailing turbulent seas. It is well known that Turner dominated the art of the sea, ceaselessly responding to contemporary maritime events during an age of increased maritime travel and trade and global naval warfare. It is no surprise then that the artist travelled to see The Columbus, a ship of such vast proportions voyaged from the Isle of Orleans across the Atlantic Ocean.

Having described what is pictured in the Brighton and Arundel sketchbook, it is worth highlighting some of the written memoranda inscribed within the book: notes written by Turner on aspects of printmaking. Turner, the art historian Luke Herrmann writes, ‘was almost constantly concerned with the production and publication of prints after his drawings’. 17 Indeed, the drawings described above made in preparation for engraving designs represent only a small fraction of the artist’s output for such publications. That this sketchbook contains detailed notes on the subject of engraving, specifically on the emerging technique of lithography, then, is not surprising given Turner’s frequent and sustained professional contact with engravers and printmakers. He necessarily would have kept himself abreast of the developing technologies of picture reproduction. On Tate D18313; Turner Bequest CCX 2 the artist has transcribed recipes for the chemicals used in the lithographic method from Alois Senefelder’s Complete Course in Lithography (1818), a copy of which he himself owned.18 These inscriptions are followed by instructions on how to clean plates for engraving with ‘acetate of Alumina’ (Tate D18314; Turner Bequest CCX 2a), recipes for pigments (Tate D18315; Turner Bequest CCX 3) and a cure for dry rot using ‘White Arsenic’ (Tate D18316; Turner Bequest CCX 3a).

This sketchbook offers a number of valuable insights into Turner’s business and private life. His pictures of Brighton Chain Pier, Kirkstall Lock and the wrecked freighter Columbus embody the artist’s searching and curious exploration of modern existence, of contemporary events and industrial change. Inscriptions such as a travel itinerary and the list of commissioned work for printmakers remind us that Turner was very much a working artist, actively on the road to gather material for new projects and almost continuously professionally engaged to produce designs for print publications. Notes about engraving and recipes for pigments, meanwhile, show that Turner was committed to the activity of printmaking and painting as an art, drawing on new knowledge, resources and technological developments to produce his work in the most up-to-date and sophisticated way. Finally, sketches like the Farnley sunset studies, where Turner records fugitive cloud formations streaking across a retreating sun, reveal ‘off duty’ moments in the artist’s life, when he wished to remember times he was among close friends.

Ian Warrell, ‘J.M.W. Turner in Brighton’ in David Beevers (ed.), John Roles, Ian Warrell and others, Brighton Revealed: Through Artists’ Eyes c.1760-c.1960, exhibition catalogue, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery 1995, p.33.

See Alice Rylance-Watson, ‘‘Rivers of England’ Watercolours and Related Works c.1822–4’, March 2013, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, August 2014, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/rivers-of-england-watercolours-and-related-works-r1146362 ; See also Andrew Wilton, J.M.W. Turner: His Life and Work, Fribourg 1979, p.400 under no.854

See Luke Herrmann’s entry ‘The Picturesque Views of the Southern Coast of England’ in Evelyn Joll, Martin Butlin and Luke Herrmann (eds.), The Oxford Companion to J.M.W. Turner, Oxford 2001, p.307.

‘Chain Pier’, My Brighton and Hove, accessed 9 April 2015, http://www.mybrightonandhove.org.uk/page_id__7917.aspx?path=0p115p207p478p

‘St Nicholas’ Church’, My Brighton and Hove, accessed 10 April 2015, http://www.mybrightonandhove.org.uk/page_id__8850.aspx

For more information on Turner’s relationship with Fawkes and his stays at Farnley Hall see David Hill, ‘Sketchbooks and Drawings Associated with Farnley Hall and Related Yorkshire Subjects c.1808–24’, July 2010, revised by David Blayney Brown, April 2013, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, September 2014, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/sketchbooks-and-drawings-associated-with-farnley-hall-and-related-yorkshire-subjects-r1149249

See A.J. Finberg, ‘Turner’s Newly Discovered Yorkshire Sketchbook’, Connoisseur, Octover 1935, pp.185–87; Ian Warrell ‘The Farnley-Munro Sketchbook’, Lowell Libson Ltd., London 2014, pp.89–102 (view online at http://www.lowell-libson.com/downloads/files/2014Catalogue.pdf )

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Saturday, 20 November 1824, no.CXIII, vol.IV, London 1824, pp.353–56.

Table of Concordance:

The table below lists the folios of the Brighton and Arundel sketchbook next to their respective Tate accession and Turner Bequest numbers. Any inconsistencies in number or order are recorded here. In his Inventory A.J. Finberg explains that Tate D18383 and D18384 have the Turner Bequest numbers ‘CCX 44 55’ and ‘CCX 44 65’ because these two leaves were once included in a bundle of blank sheets organised by John Ruskin. The sheets within this bundle were numbered 44 1–44 76. Sheets ‘44 65’ and ‘44 55’ were later removed by Finberg because they contained previously overlooked sketches and were replaced by him into this sketchbook and stamped ‘CCX 44 55’ and ‘CCX 44 66’.19 Folios 48 and 49 recto have no Tate accession number and no Turner Bequest number. They are original to the sketchbook but were not numbered by Finberg.

| Folio | Tate Number | Turner Bequest Number |

| 42 Recto | D18379 | CCX 42 |

| 43 Recto | D18477 | CCX 93 |

| 43 Verso | D18478 | CCX 93a |

| 44 Recto | D18380 | CCX 43 |

| 44 Verso | D18381 | CCX 43a |

| 45 Recto | D18382 | CCX 44 |

| 46 Recto | D18383 | CCX 44 55 |

| 47 Recto | D18384 | CCX 44 65 |

| 48 Recto | No Tate number | No Turner Bequest number |

| 49 Recto | No Tate number | No Turner Bequest number |

| 50 Recto | D18385 | CCX 45a |

| 51 Recto | D18386 | CCX 45b |

| 51 Verso | D18387 | CCX 45c |

| 52 Recto | D18388 | CCX 46 |

| 53 Recto | D18389 | CCX 47 |

| 54 Recto | D18390 | CCX 48 |

| 54 Verso | D18391 | CCX 48a |

| 55 Recto | D18392 | CCX 49 |

| 56 Recto | D18393 | CCX 50 |

| 56 Verso | D18394 | CCX 50a |

| 57 Recto | D18395 | CCX 51 |

| 57 Verso | D18396 | CCX 51a |

| 58 Recto | D18297 | CCX 52 |

| 58 Verso | D18398 | CCX 52a |

| 59 Recto | D18399 | CCX 53 |

| 59 Verso | D18400 | CCX 53a |

| 60 Recto | D18401 | CCX 54 |

| 60 Verso | D18402 | CCX 54a |

| 61 Recto | D18403 | CCX 55 |

| 61 Verso | D18404 | CCX 55a |

| 62 Recto | D18405 | CCX 56 |

| 63 Recto | D18406 | CCX 57 |

| 63 Verso | D18407 | CCX 57a |

| 64 Recto | D18408 | CCX 58 |

| 64 Verso | D18409 | CCX 58a |

| 65 Recto | D18410 | CCX 59 |

| 65 Verso | D18411 | CCX 59a |

| 66 Recto | D18412 | CCX 60 |

| 66 Verso | D18413 | CCX 60a |

| 67 Recto | D18414 | CCX 61 |

| 67 Verso | D18415 | CCX 61a |

| 68 Recto | D18416 | CCX 62 |

| 68 Verso | D18417 | CCX 62a |

| 69 Recto | D18418 | CCX 63 |

| 69 Verso | D18419 | CCX 63a |

| 70 Recto | D18420 | CCX 64 |

| 70 Verso | D18421 | CCX 64a |

| 71 Recto | D18422 | CCX 65 |

| 71 Verso | D18423 | CCX 65a |

| 72 Recto | D18424 | CCX 66 |

| 72 Verso | D18425 | CCX 66a |

| 73 Recto | D18428 | CCX 68 |

| 73 Verso | D18429 | CCX 68a |

| 74 Recto | D18430 | CCX 69 |

| 74 Verso | D18431 | CCX 69a |

| 75 Recto | D18432 | CCX 70 |

| 75 Verso | D18433 | CCX 70a |

| 76 Recto | D18434 | CCX 71 |

| 76 Verso | D18435 | CCX 71a |

| 77 Recto | D18436 | CCX 72 |

| 77 Verso | D18437 | CCX 72a |

| 78 Recto | D18438 | CCX 73 |

| 78 Verso | D18439 | CCX 73a |

| 79 Recto | D18440 | CCX 74 |

| 79 Verso | D18441 | CCX 74a |

| 80 Recto | D18442 | CCX 75 |

| 80 Verso | D18443 | CCX 75a |

| 81 Recto | D18444 | CCX 76 |

| 81 Verso | D18445 | CCX 76a |

| 82 Recto | D18446 | CCX 77 |

| 82 Verso | D18447 | CCX 77a |

| 83 Recto | D18448 | CCX 78 |

| 83 Verso | D18449 | CCX 78a |

| 84 Recto | D18450 | CCX 79 |

| 84 Verso | D18451 | CCX 79a |

| 85 Recto | D18452 | CCX 80 |

| 85 Verso | D18453 | CCX 80a |

| 86 Recto | D18454 | CCX 81 |

| 86 Verso | D18455 | CCX 81a |

| 86 Recto | D18456 | CCX 82 |

| 87 Verso | D18457 | CCX 82a |

| 88 Recto | D18458 | CCX 83 |

| 88 Verso | D18459 | CCX 83v |

| 89 Recto | D18460 | CCX 84 |

| 89 Verso | D18461 | CCX 84a |

| 90 Recto | D18462 | CCX 85 |

| 90 Verso | D18463 | CCX 85a |

| 91 Recto | D18464 | CCX 86 |

| 91 Verso | D18465 | CCX 86a |

| 92 Recto | D18466 | CCX 87 |

| 92 Verso | D18467 | CCX 87a |

| 93 Recto | D18468 | CCX 88 |

| 93 Verso | D18469 | CCX 88a |

| 94 Recto | D18470 | CCX 89 |

How to cite

‘Brighton and Arundel sketchbook 1824’, sketchbook, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, August 2016, https://www