Turner Bequest CLXXXIII

Sketchbook with paper covered boards bound with a brown leather spine and corners, and a brass clasp [missing]

82 leaves of white wove writing paper, approximate page size 253 x 200 mm

Made by William Balston, Springfield Mill, Kent; various pages watermarked ‘J WHATMAN | 1814’

82 leaves of white wove writing paper, approximate page size 253 x 200 mm

Made by William Balston, Springfield Mill, Kent; various pages watermarked ‘J WHATMAN | 1814’

Front cover is stamped in black ‘CLXXXIII’ top right.

Inside front cover is numbered ‘151’ as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest, inscribed in black ink ‘No.151 | H.S. Trimmer’ and initialled in pencil by Charles Lock Eastlake ‘C.L.E.’ and John Prescott Knight, ‘JPK’. Also inscribed by an unknown hand in pencil ‘CLXXXIII’ top centre left.

Back cover is inscribed by an unknown hand in black pen and ink ‘231’ [encircled] top left, inverted.

Inside front cover is numbered ‘151’ as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest, inscribed in black ink ‘No.151 | H.S. Trimmer’ and initialled in pencil by Charles Lock Eastlake ‘C.L.E.’ and John Prescott Knight, ‘JPK’. Also inscribed by an unknown hand in pencil ‘CLXXXIII’ top centre left.

Back cover is inscribed by an unknown hand in black pen and ink ‘231’ [encircled] top left, inverted.

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

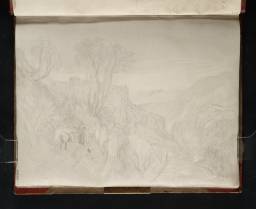

Turner used this sketchbook during his first tour of Italy in 1819, one of twenty-three related to that trip. As the artist’s own label once indicated, the contents comprise views of Tivoli, a town situated amidst the mountains, twenty miles east of Rome.1 The expedition possibly took place in early October just prior to his departure from Rome to Naples,2 and judging by the large number of studies must have lasted at least a couple of days.

An alluring combination of dramatic landscape, ancient architecture and classical sites, Tivoli was considered an essential component of the ‘Grand Tour’ itinerary and could be reached within a four-hour carriage drive from the Eternal City.3 With its picturesque ruins, wooded hills, panoramic views across the Roman Campagna, and most strikingly of all, the many cascades of the River Aniene (known in Latin as the Anio), the town possessed a natural appeal for Turner. During his own 1819 Italian tour he devoted a significant amount of energy to exploring its sights and scenery; see the introduction to the Tivoli and Rome sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CLXXIX). By far the largest number of studies in this sketchbook are devoted to the town’s most famous landmarks: the so-called Temple of Vesta and the ‘Grand Cascade’ of the River Aniene, and the Santuario di Ercole Vincitore (known in Turner’s day as the Villa of Maecenas), with the cascatelli (or cascatelle), the lesser cascades which streamed from underground channels into the steep valley to the north of the town. Turner made close-up, detailed drawings of the architectural points of interest of these two sites. He also repeatedly depicted them in relation to their surroundings from a variety of viewpoints including the eastern heights of Monte Catillo, the floor of the valley near Ponte Acquoria, and from various locations on the road skirting the end of the valley such as the Convent of San Antonio and the Santuario di Quintiliolo (Church of the Madonna of Quintiliolo). He relished the way that the architecture appeared to be hanging above the gorge, and he frequently chose a low viewpoint looking up, or a high viewpoint looking across or down, which enabled him to explore spatial depth and perspective.

The unique combination of history and landscape encouraged Turner to vary his visual response to Tivoli. As in Rome and Naples he was inspired to experiment with different media, and many of the swift outline views in the Tivoli and Rome sketchbook are revisited in more detailed tonal compositions in this sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CLXXXIII). Most of the pages are pre-prepared with a flat grey wash which provides a natural mid-tone background for chiaroscuro effects. Turner created white highlights by lifting or rubbing the wash to reveal the original colour of the paper beneath. He also diversified his handling of the pencil, employing expressive free lines and hatching, and very deep soft shading to exploit the full tonal range of light and dark. This enabled him to explore the experience and atmosphere naturally suggested to him by the terrain; the dusky shadows of the shady valleys, rocky slopes and groves of olive and cypress trees, as well as the startling whiteness of the cascades and river. Cecilia Powell has also discussed the phenomenon of haze or mist which regularly veils the town in shades of grey.4 Further Tivoli subjects on grey paper, as well as two coloured studies, can also be found in the Naples: Rome C. Studies sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest CLXXXVII).

Tivoli appears to have represented a highlight of Turner’s Italian travels, being one of the key locations mentioned to Joseph Farington the day after his return to London in 1820.5 He was also inspired enough to make a second visit to the town during his 1828 trip to Rome (see the Roman and French sketchbook, Tate; Turner Bequest CCXXXVII). Yet the large accumulated amount of sketchbook material resulted in no immediate studio paintings and very little finished work of significance. A couple of colour beginnings speculatively dated 1820 may represent the intention to produce a topographical view: see a sheet in the Turner Bequest (Tate D17185; Turner Bequest CXCVI U) and Tivoli (Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester).6 However, it is not possible to conclusively link either study to the period after the 1819 tour. The first and only finished Tivoli watercolour was the conventional scene of the Temple of Vesta produced as a vignette illustration for Rogers’s Italy, 1830 (Tate D27683; Turner Bequest CCLXXX 166). Turner also seems to have been consistently interested by the view of the Santuario di Ercole Vincitore seen from the north-east. He considered developing this motif for Rogers’s Italy (see Tate D27605; Turner Bequest CCLXXX 88) and ultimately explored a similar composition within an oil sketch, Tivoli, the Cascatelle circa 1827–8 (Tate, N03388) and an unfinished painting, Tivoli: Tobias and the Angel circa 1835 (Tate, N02067).7 Tivolean elements may also be discerned in paintings such as Modern Italy, the Pifferari exhibited 1838 (Glasgow Museums)8, and The Rape of Proserpine or Pluto Carrying off Proserpine exhibited 1839 (National Gallery of Art, Washington).9

During the nineteenth-century survey of the Turner Bequest, John Ruskin removed twenty-five pages from the Tivoli sketchbook and framed a further fifteen for inclusion in the Oxford Loan Collection in 1878 (ie. D15467–D15481; Turner Bequest CLXXXIII 1–15). Finberg’s titles for the latter group follow those given by Ruskin. Although the leaves were later reunited as one bound object, Finberg documented that no record was kept of the order and therefore the original sequence of the sketchbook was impossible to reconstruct.10 It might be assumed that continuity existed between subjects of a similar theme, for example successive views of the Santuario di Ercole Vincitore seen from the valley, or the three studies of the interior of the temple. However, it seems unlikely that the first distribution of the pages can ever be confidently reconstituted.

Finberg records a label on the back inscribed by the artist ‘13. Tivoli.’ which is now missing or destroyed. Finberg 1909, p.540.

As discussed by Cecilia Powell, Turner in the South: Rome, Naples, Florence, New Haven and London 1987, p.[77] note 17.

An entry in Farington’s diary for Wednesday 2 February 1820 reads ‘Turner returned from Italy yesterday; had been absent 6 months to a day – Tivoli, Venice, Albano – Terni – fine’. Quoted Powell 1987, p.78.

Technical notes

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Tivoli sketchbook 1819’, sketchbook, March 2010, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www