A ‘New Face’ at the Co-op

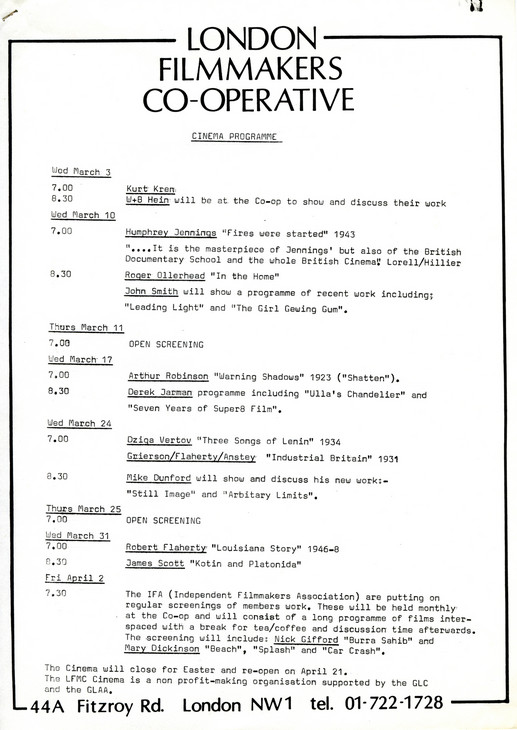

Programme listing for the premiere of John Smith's The Girl Chewing Gum 1976 at the London Film-makers' Co-operative on 10 March 1976

Courtesy of British Artists' Film and Video Study Collection, Central St Martins

Fig.1

Programme listing for the premiere of John Smith's The Girl Chewing Gum 1976 at the London Film-makers' Co-operative on 10 March 1976

Courtesy of British Artists' Film and Video Study Collection, Central St Martins

The major part of this week’s show is by a young film-maker who is something of a ‘new face’. Though he has shown a film in a group programme at the Co-op before, and one of his films, ‘Associations’, was recently seen on BBC2’s ‘First Picture Show’, this is the first chance to look at a number of his films in one go. His work is extremely interesting, accomplished, and has a surprising variety. As well as ‘Associations’ which weaves a complex game of word-image puns with entertaining wit, he will show ‘William and the Cows’, one of the most surreal films I have ever seen; ‘Leading Light’, a rather fine short film about sunlight, artificial light, and exposure levels; and ‘Subjective Tick-Tocks’, about measured time, rhythm, and camera movement. The programme will have the first screening of his newest film, ‘The Girl Chewing Gum’, which promises to be as good viewing as the rest ... A lively show full of ideas.1

Smith has no strong recollection of the event, speculating, ‘I suspect like most screenings, it was fine but it was an anti-climax’.2 It was, however, the occasion of his first meeting with Le Grice, who recommended that the emerging filmmaker change his name due to its plainness and ubiquity. Smith, of course, refused, sticking to a given name that the artist Cornelia Parker has rightly described as ‘a perfect fit, a ready made’ due to the manner in which it suits the ‘ironic embracing of the ultra mundane’ one finds in his films.3

Programme notes for the premiere of John Smith's The Girl Chewing Gum 1976 at the London Film-makers' Co-operative on 10 March 1976

Courtesy of British Artists' Film and Video Study Collection, Central St Martins

Fig.2

Programme notes for the premiere of John Smith's The Girl Chewing Gum 1976 at the London Film-makers' Co-operative on 10 March 1976

Courtesy of British Artists' Film and Video Study Collection, Central St Martins

In the mid-1970s, the London Film-makers’ Co-operative was a space of vibrant dialogue concerning the political efficacy of avant-garde filmmaking. On 10 and 11 February 1976, exactly one month before the first screening of The Girl Chewing Gum, the Co-op hosted a two-day seminar called ‘Theory of Avant-Garde Film Practice’. Based on the November 1975 special issue of Studio International devoted to British and European experimental filmmaking, the event saw filmmaker-theorists Peter Gidal, Malcolm Le Grice and Peter Wollen each present papers, show films and participate in a chaired discussion. The Studio International issue up for debate featured two influential texts exemplary of the ethos that prevailed at the Co-op during this period: Gidal’s ‘Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film’ and Wollen’s ‘The Two Avant-Gardes’. Taken together, they are immensely helpful in reconstituting something of the original production and reception contexts for The Girl Chewing Gum.

Structural/materialist film derived its name from the ‘structural film’ that had emerged in the United States in the late 1960s, labelled as such by film historian P. Adams Sitney in a text first published in Film Culture 47 in the summer of 1969. Structural film, in Sitney’s view, ‘insists on its shape, and what content it has is minimal and subsidiary to the outline’.7 Exemplary figures of this tendency included Hollis Frampton, Ernie Gehr and Michael Snow, a diverse group who nevertheless shared an insistence on a reflexive interrogation of the apparatus. In this drive to isolate and investigate the medium-specific qualities of film, structural film constituted the high modernist moment of American experimental cinema, and had nothing to do with the theoretical school of French structuralism. In the British context, the addition of ‘materialist’ signalled the presence of an overt political investment, appending a commitment to Marxian dialectical materialism to the Americans’ anti-illusionist probing of the materiality of the filmic medium. Gidal’s piece in Studio International programmatically outlined the aims and methods of this tendency, calling for an emptying of content, a demystificatory rejection of identification, a total repudiation of narrativity, an emphasis on process and a focus on the material relations that exist between film and viewer. Gidal was rather mandarin in his anti-narrative position, rejecting even exercises in ‘narrative-deconstruction’ for not going far enough in the quest to banish the spectre of storytelling from the cinema.8

Wollen’s ‘The Two Avant-Gardes’ offered a rather different position, particularly on the issue of narrative. Wollen divided experimental practice in Europe into two camps: those aligned with the Co-op and pursuing the kinds of strategies Gidal elaborates, and those like Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, and Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, who made Brechtian film essays. For Wollen, the filmmakers of the Co-op constituted a painterly avant-garde interested in the expulsion of language and narrative, and invested in a search for cinematic specificity that he saw as ‘deceptively purist and reductive’.9 Gidal and Wollen both described the contemporaneous field of practice as one in which dominant cinema was the object of an assault to be accomplished by intense work on the signifier. The point of contention between them lay in whether this would be most successful through the evacuation of content proper to structural/materialist film or whether it might be, in Wollen’s words, ‘possible to work within the space opened up by the disjunction and dislocation of signifier and signified’.10 This would mean not jettisoning content (the ‘signified’) entirely, but retaining it while insistently putting into question its relation to form (the ‘signifier’). For Wollen, language and narrative were sites of intervention too important to be cast out of the purview of avant-garde filmmaking.

Writing in 1997 of the influence of structural/materialist film on his practice, Smith reflected, ‘Although I did not embrace the movement wholeheartedly its propositions were fundamental in the formation of an approach to film-making that I have pursued consistently ever since’.11 Like Gidal – who was, it is worth recalling, not only a major filmmaker-theorist at the Co-op but also Smith’s tutor at the RCA – Smith took up the task of making a film that rejected the creation of a seamless diegetic reality in favour of emphasising filmic construction, reflexivity and the shifting dynamics between spectator and text. But in maintaining a keen interest, however critical, in the codes that governed the production of meaning within narrative cinema (be it fiction or documentary), Smith was positioning himself outside the orthodoxy of structural/materialist film. Gidal’s notion that film ‘must minimise the content in its overpowering, imagistically seductive sense, in an attempt to get through this miasmic area of “experience” and proceed with film as film’ is wholly inapplicable to The Girl Chewing Gum, which remains purposefully immersed in the ‘miasmic area’ of a street corner and all of its quotidian activities.12 The Girl Chewing Gum does not advance ‘film as film’ (i.e. material) but rather investigates the signifying conventions of cinema. Moreover, it does so through two long takes, restricting itself to an element of the cinematographic vocabulary traditionally aligned with a faith in the recording capabilities of the apparatus. The film is, at a very basic level, a documentary – albeit a peculiar one. All of this places it at odds with Gidal’s statement that ‘An avant-garde film defined by its development towards increased materialism and materialist function does not represent, or document, anything’.13

For all these departures from the structural/materialist line, The Girl Chewing Gum is not any more at home within Wollen’s ‘second’, essayistic avant-garde. Smith does share with the Godard-Straub axis a strong interest in semiotics and the conviction that, as the literary and cultural theorist Roland Barthes had suggested in 1970, ‘The contemporary problem is not to destroy the narrative but to subvert it’.14 The Girl Chewing Gum never rejects the codes of dominant cinema entirely, but rather playfully entertains them so as to render their operations and occlusions visible. Language is tremendously important. However, the film departs sharply from the institutional and economic contexts of the second avant-garde in that it was made within an artisanal mode of production and depended on the Co-op for its distribution and exhibition. Even at the level of the text, it lacks the disjunctive montage employed by many of the filmmakers Wollen discusses, as well as their palimpsestic intertextuality. In its isolation of a single filmic device – in this case, the function of the voiceover – it is in a closer relation with the kind of reductive forms of structural/materialist film.

If anything, The Girl Chewing Gum might be seen to have most in common with American films of the period such as Michael Snow’s Wavelength 1967 and A Casing Shelved 1970, or Hollis Frampton’s Zorns Lemma 1970 and (nostalgia) 1971, which engage with narrative and language-image relationships while reflecting on the specificity of cinematic representation. Indeed, looking back on the period surrounding 1975 in his 1997 PhD thesis, the first three filmmakers Smith lists as inspirational to him at this time are Snow, Frampton and the Austrian Peter Kubelka.15 Although Smith has never seen A Casing Shelved and did not see (nostalgia) until after making The Girl Chewing Gum,16 both films show an especially close kinship with his work in that they make use of a voiceover delivered by or as the filmmaker to describe the image, only to then emphasise the lack of fit between the two. They present themselves as failed attempts to master the visual field. In A Casing Shelved, Snow describes in great detail a 35 mm slide of a shelf in his studio. As he put it, ‘I wanted to say everything that could be said about it’.17 Yet despite this stated desire for a complete account, Snow is incapable of exhausting the photograph or taking inventory of its contents in a stable manner. His description of the slide oscillates between naming the things depicted in it – a wine bottle, a paint can – and naming its forms of graphic representation. An electric cord, for instance, is called ‘a black line’, while a cardboard box is a ‘brown rectangle’. Contaminating these two registers of denomination, Snow shuttles between the virtuality of the represented scene and the material actuality of the photograph. In (nostalgia), Snow reads a text written by Frampton in the first person, describing a series of photographs taken by the latter which appear one at a time onscreen, burning on a hotplate. But instead of creating a tight suture between text and image, the description heard corresponds not to the photograph onscreen but to the photograph that will follow it. A gap opens between what is said and what is seen, just as it does in The Girl Chewing Gum.

Beyond the similarities in formal technique and semiotic inquiry, The Girl Chewing Gum shares with these two films a quality not often associated with avant-garde cinema: humour. A Casing Shelved and (nostalgia) showcase the dry wit of their makers, both mobilising Snow’s droll Upper Canadian monotone to deliver a cerebral amusement that stops just short of being properly funny. While The Girl Chewing Gum is wry as well, it is worth noting its differences in tone and sensibility from its American counterparts. Ian Christie has suggested that Smith’s particular brand of humour might best be seen in the lineage of ‘English eccentricity’, a particularly national tradition that he sees as marked by a quirky preoccupation with the ‘unfashionably local’, a fascination for ‘the mundane’ and an interest in techniques of defamiliarisation that would ‘show the illogic of the usual’.18 While such characteristics might also be said to be present in the American films as well, A Casing Shelved and (nostalgia) are marked by a dry flatness that recalls the affect of conceptual art and minimalism, found nowhere in The Girl Chewing Gum. For Christie, Smith is an inheritor of the sensibility of the English writer G.K. Chesterton, like him using ‘the everyday topography of London as a foil for the cosmic struggle between anarchy and order, which is supposedly taking place beneath and above its streets’.19 Both Frampton and Snow include autobiographical elements, but the world of their films is very distinctly the art world rather than the quotidian life of their neighbourhood or city. The voice of (nostalgia) is emphatically a reading voice, possessing none of Smith’s responsive, exuberant flamboyance and never reaching the levels of absurdism and, by extension, entertainment that one finds in his film.

The Girl Chewing Gum, then, shows certain connections to contemporaneous American tendencies while remaining distinctively English. It is a unique film that is ultimately inassimilable to the categories that were commonly used to describe the prevailing tendencies in avant-garde practice in Britain at the time of its production. In this it is not alone; the paradigms outlined in texts such as ‘Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film’ and ‘The Two Avant-Gardes’ are always more uniform and rigid than the diverse field of activity they seek to chart. Nonetheless, rehearsing the film’s points of contact and lack of fit with such categories remains a useful exercise, for it enables one to situate The Girl Chewing Gum within the broader field of discourses and practices from which it emerged and in which it was first encountered.

Notes

Malcolm Le Grice, untitled film listing, Time Out, 5–11 March 1976, p.64. In addition to the five films Le Grice mentions, the programme also featured Words 1972–3, made with Lis Rhodes, and Nine Short Stories 1975.

Cornelia Parker, ‘John Smith’s Body’, in Mark Cosgrove and Josephine Lanyon (eds.), John Smith: Film and Video Works, 1972–2002, Bristol 2002, p.8.

See, for example, www.lux.org.uk/collection/works/the-girl-chewing-gum , accessed 11 June 2015, and http://johnsmithfilms.com/selected-works/the-girl-chewing-gum , accessed 11 June 2015.

A longer version of the original text was included in a 1982 pamphlet entitled ‘John Smith Films 1975–82’ (available in the John Smith file at the British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection), but it does not appear to have been used since.

Programme notes of the London Film-makers’ Co-operative, 10 March 1976, 1p, courtesy of British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection.

P. Adams Sitney, Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 1973–2000, 3rd edn, New York 2002, p.348.

Although Gidal allowed that such exercises ‘are not irrelevant as sociological insight into certain filmic operations’, he saw them as ultimately reproducing through filmmaking a practice better suited to writing, a fact that he saw as having ‘now dawned, perhaps, on the overzealous graduates who wish to make statements about certain usages of narrative’. Peter Gidal, ‘Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film’, Studio International, vol.190, no.978, November–December 1975, p.190.

Peter Wollen, ‘The Two Avant-Gardes’, in Philip Simpson, Andrew Utterson and K.J. Shepherdson (eds.), Film Theory: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies, London 2004, p.135.

John Smith, ‘Real Fiction’, paper submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Smith’s PhD, University of East London, December 1997, pp.3–4. Courtesy of British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection.

Ibid. Yet it is worth noting that Gidal was a supporter of the film: after it was rejected by the Edinburgh Film Festival, he wrote to Linda Myles, the festival director, to argue for its inclusion on her programme. John Smith, interview with the author, 8 December 2014.

Roland Barthes, ‘The Third Meaning’, in Image Music Text, trans. by Stephen Heath, New York 1977, p.64, emphasis in text. Gidal was very clear in his opposition to this position in his 1979 text ‘The Anti-Narrative’: ‘What is not needed is “a different narrative”, “at the limit of fictions of unity” (Stephen Heath), “an enigma, contradictory”: The notion of “the limit” is both a Barthesian and Metzian notion, one which in fact refuses the necessity of denial’. See Peter Gidal, ‘The Anti-Narrative’, Screen, vol.20, no.2, 1979, p.78.

Smith recalls that the first films he saw by Snow and Frampton were <---> (known as Back and Forth) of 1969 and Zorns Lemma, respectively. Although he saw these films around the same time he made The Girl Chewing Gum, he does not recall whether it was before or after, but notes that ‘both made a big impression on [him]’. John Smith, email correspondence with the author, 3 April 2015.

Michael Snow quoted in ‘The Camera and the Spectator: Michael Snow in Discussion with John Du Cane’, in Michael Snow and Louise Dompierre, The Michael Snow Project: The Collected Writings of Michael Snow, Waterloo 1994, p.91.

How to cite

Erika Balsom, ‘A ‘New Face’ at the Co-op’, September 2015, in Erika Balsom (ed.), In Focus: 'The Girl Chewing Gum' 1976 by John Smith, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www