Wrestling

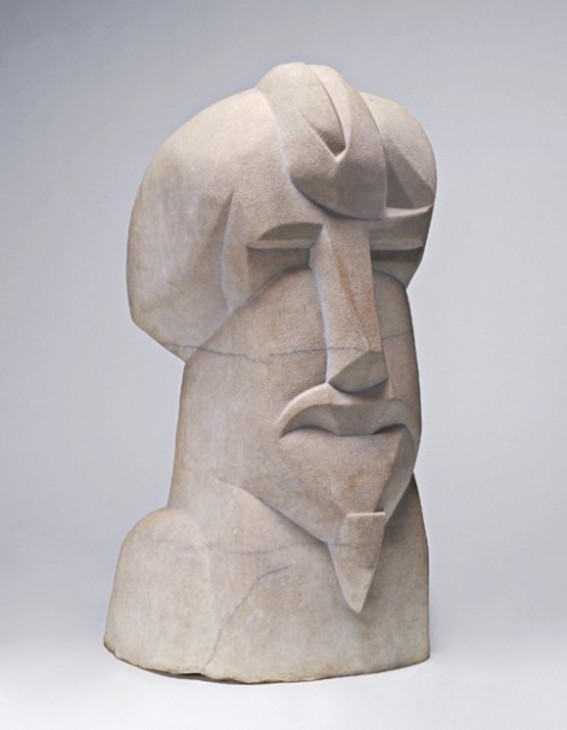

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Wrestlers 1914, cast 1965

Plaster

711 x 927 x 76 mm

Tate T00837

Presented by Kettle's Yard Collection Cambridge 1966

Tate

Fig.1

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Wrestlers 1914, cast 1965

Plaster

711 x 927 x 76 mm

Tate T00837

Presented by Kettle's Yard Collection Cambridge 1966

Tate

George Hakenschmidt, Complete Science of Wrestling (1909).1

Gaudier-Brzeska’s two wrestlers are locked in a hold (fig.1). The white plaster ground contained within a rectangular wooden frame serves as a wrestling mat for these lithe but physically powerful bodies. The fight appears to have reached a moment of stasis: the head of the wrestler who dominates the upper part of the relief rests on his opponent whose arched back curves underneath him. To the right-hand side there is a complex entanglement of hands, arms, calves and thighs.

The relief does not depict any one particular moment in a wrestling match but is a synthesis of the contact and combat which Gaudier-Brzeska had observed on his numerous visits to a London wrestling gym. It represents – to borrow the title from the weekly update on wrestling from the leading physical culture journal of Gaudier-Brzeska’s day, Health & Strength – the ‘matters of the mat’: a visual and material combination of all the entanglements, the positions, the poses, the rolls, turns and touches that are possible in any one wrestling match.

Towards the end of 1912 Gaudier-Brzeska visited a wrestling gym to make sketches of the fighters. Around the same time he enrolled in a life class in Chelsea where, as someone who had not attended art school before, he was exposed to the nude life model for the first time. Wrestlers, then, might be understood as a composite of the physical and visual memories of the gymnasium and the life class at a moment in Gaudier-Brzeska’s career when he was particularly fascinated by the representation of the body in movement. This overlapping of the wrestling club and the life class can be traced visually through Gaudier-Brzeska’s depictions of the fighting body and in written accounts of Gaudier-Brzeska’s time in London between 1911 and 1914.

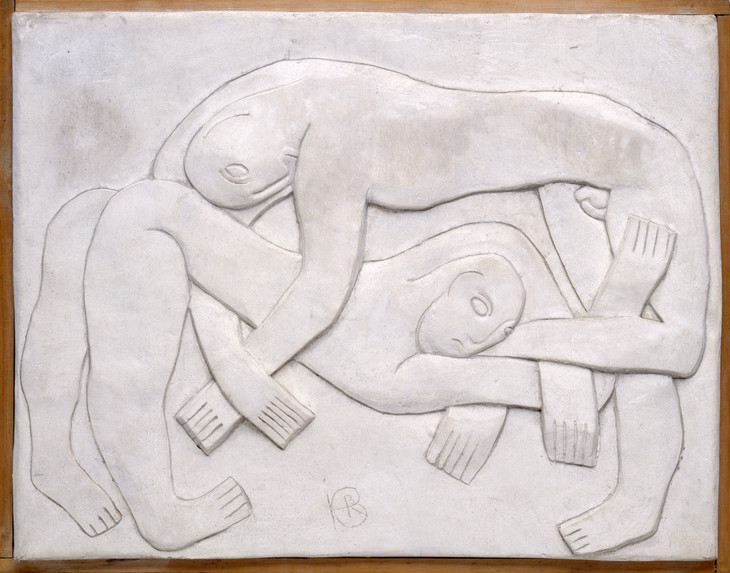

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Two Wrestlers 1914

Graphite on paper

160 x 207 mm

Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge

Fig.2

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Two Wrestlers 1914

Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge

The Wrestlers relief is part of a series of drawings, designs and one other sculpture depicting wrestlers that Gaudier-Brzeska executed in an intense burst of activity between 1912 and 1914, including the drawing Two Wrestlers (fig.2). He used his pen and pencil studies to explore the mechanics and musculature of the athletic male body, and the drawings and sculptures need to be examined together as part of a larger project of observing the trained and disciplined body in movement.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Wrestler 1912, cast 1945

Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

Fig.3

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Wrestler 1912, cast 1945

Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

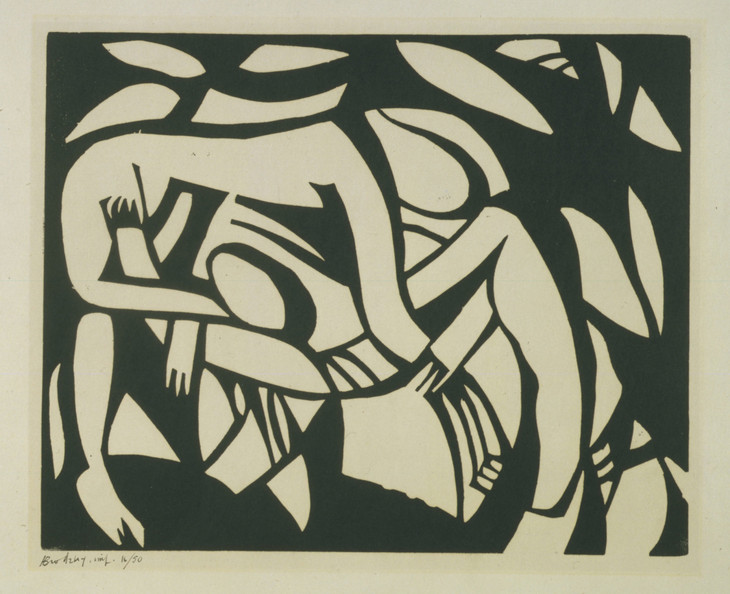

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Tray. The Wrestlers 1913

Photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.4

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Tray. The Wrestlers 1913

Photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Wrestlers 1913

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.5

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Wrestlers 1913

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In the gym

On Thursday 28 November 1912 Gaudier-Brzeska wrote to his companion, Sophie Brzeska, to tell her of a meeting with an engineer called Charles Wheeler, whom he had met through his acquaintance with Charles’s brother, the actor Ewart Wheeler. According to Gaudier-Brzeska, Charles Wheeler was the recipient of ‘big contracts of copper, wire, carriages, motors, etc., for firms in Birmingham, and he has a great deal of influence with these people’.5 Wheeler was going to introduce the artist to the manufacturers of ‘motor mascots’ and ‘electric radiator ornaments’.6 He was also an avid sports fan and commissioned Gaudier-Brzeska to ‘make two little statues in plaster – one of a wrestler and the other of a bather – which he will have cast in bronze by one of his firms’.7 No extant copy of the bather survives, or perhaps it was never made, but Gaudier-Brzeska did execute the wrestler (fig.4).8 In preparation Gaudier-Brzeska reported to Sophie that he was ‘going to see wrestling in the evenings two or three times, which will give me some good sketches; I am also going to see some boxing matches and diving, and I’m terribly excited about it’.9

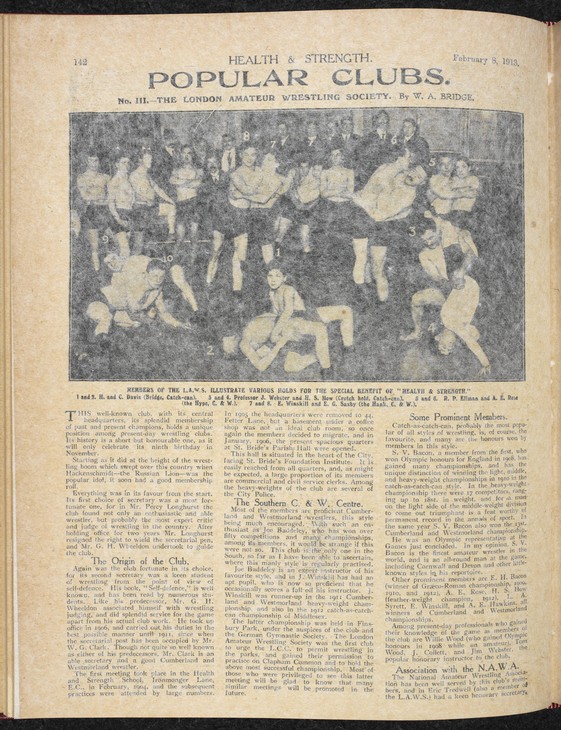

W.A. Bridge

'Popular Clubs. The London Amateur Wrestling Society', Health and Strength, 8 February 1913

Fig.6

W.A. Bridge

'Popular Clubs. The London Amateur Wrestling Society', Health and Strength, 8 February 1913

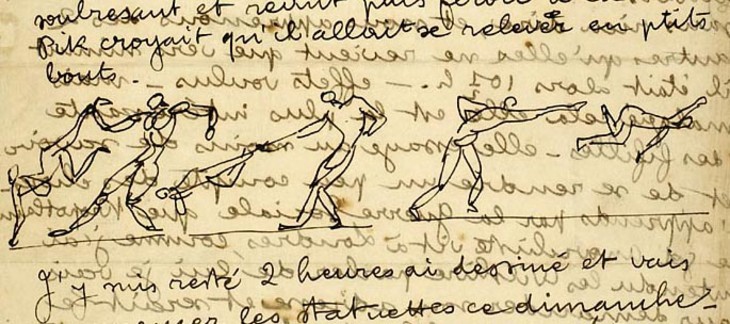

Writing to Sophie of this visit in a state of great excitement, Gaudier-Brzeska enthused about what he had seen, and penned a small sketch of wrestlers practising different moves (fig.7):

Last night I went to see the wrestlers – God! I have seldom seen anything so lovely – two athletic types, large shoulders, taut, big necks like bulls, small in the build with firm thighs and slender ankles, feet sensitive as hands, and not tall. They fought with amazing vivacity and spirit, turning in the air, falling back on their heads, and in a flash were up again on the other side, utterly incompressible. They have reached such a state of perfection that one can take the other by a foot and, without exaggeration, can whirl him five times round and round himself, and then let go so that the other flies off like a ball and falls on his head – but he is up in a moment and back again more ferocious than ever to the fight. [I] thought he would be smashed to bits. I stayed and drew for two hours and am going to begin the statuettes on Sunday.13

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Letter to Sophie Brzeska dated 3 December 1912

Courtesy of the Albert Sloman Library, University of Essex

Fig.7

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Letter to Sophie Brzeska dated 3 December 1912

Courtesy of the Albert Sloman Library, University of Essex

Gaudier-Brzeska was evidently enthralled not only by the strength of the wrestlers, who were small in build, like himself, but also by the energy, spectacle and affective power of watching the fight. The homosocial spheres of the gym and the ring were, in the early twentieth century, spaces in which the male body ‘was the legitimate object of a male gaze’.14 Gaudier-Brzeska transferred the excitement he felt watching the wrestling in the club to his work in his new studio underneath a railway arch in Putney which was cheaper than his previous one and offered a large workspace with a concrete floor:

The studio is a marvellous place ... I am filled with inspiration ... Ideas keep rushing into my head in torrents – my mind is filled with a thousand plans for different statues, I’m in the midst of three, and have just finished one of them, a wrestler, which I think is very good. I’m also doing sketches for a dozen others. God, it’s good to have a studio!15

This series of works inspired by wrestling and wrestlers’ bodies marked a significant moment in Gaudier-Brzeska’s development as an artist. In these sketches, studies and sculptures, he focused incessantly on the body, experimenting with the representation of mass, muscle, shape and form. He was at pains to show his wrestling bodies as strong, supple, ‘massive’ (as Silber puts it) and dynamic. Gaudier-Brzeska was undoubtedly interested in wrestling as a sport but he was also interested in what it could offer aesthetically. While the wrestler’s body provided an opportunity for the artist to study physique and musculature, the act of wrestling provided a framed and distinct sequence of movements in which two bodies moved together. And it was precisely the rhythmic interrelationship of wrestling bodies in motion that Gaudier-Brzeska chose to focus on in the Wrestlers relief.

Moves and movement

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Dancer 1913

Plaster

787 x 230 x 216 mm

Tate T03726

Transferred from the Victoria & Albert Museum 1983

Tate

Fig.8

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Dancer 1913

Tate T03726

Tate

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Red Stone Dancer c.1913

Red Mansfield stone

432 x 229 x 229 mm

Tate N04515

Presented by C. Frank Stoop through the Contemporary Art Society 1930

Tate

Fig.9

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Red Stone Dancer c.1913

Tate N04515

Tate

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Red Stone Dancer c.1913

Red Mansfield stone

432 x 229 x 229 mm

Tate N04515

Presented by C. Frank Stoop through the Contemporary Art Society 1930

Tate

Fig.10

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Red Stone Dancer c.1913

Tate N04515

Tate

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Red Stone Dancer c.1913

Red Mansfield stone

432 x 229 x 229 mm

Tate N04515

Presented by C. Frank Stoop through the Contemporary Art Society 1930

Tate

Fig.11

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Red Stone Dancer c.1913

Tate N04515

Tate

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Red Stone Dancer c.1913

Red Mansfield stone

432 x 229 x 229 mm

Tate N04515

Presented by C. Frank Stoop through the Contemporary Art Society 1930

Tate

Fig.12

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Red Stone Dancer c.1913

Tate N04515

Tate

In Red Stone Dancer, however, vital and energetic movement is given expression in three dimensions rather than in relief, and as such are close to Gaudier-Brzeksa’s drawings of bodybuilders and athletes. Whereas the Wrestlers are emphatically male, Red Stone Dancer is ambiguously gendered, bearing prominent breasts to the front but the appearance of a male body if viewed from the back (fig.12). For these reasons it can be argued that it was Red Stone Dancer, rather than Wrestlers, that should be seen as the ‘culmination’ of Gaudier-Brzeska’s exploration of the wrestling body. In the stone piece the wrestler and the dancer are united in a powerful and supple single figure.

Wrestling and wrestlers in the life class

There are ten known sketches of wrestling made by Gaudier-Brzeska before the First World War. Given the rapidity with which he drew, there were probably many more that are now lost. Not all were drawn as a result of his visits to the London Amateur Wrestling Society. On his first visit to Charles Wheeler’s office he recognised one of the models from the life class in which he had enrolled, describing the model to Sophie as ‘the very wrestler that I like so much – a wonderful boy, strong, taut, and finely square’.18 (Gaudier-Brzeska had joined the life class only a few weeks previously, on 12 November 1912, and attended two-hour classes every Tuesday and Friday from 8 pm to draw from the nude. The fee was five shillings for a five-week course.)

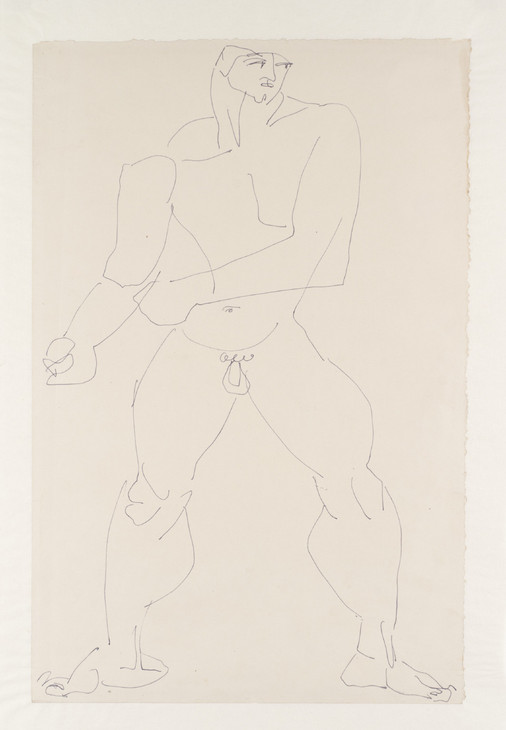

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Wrestler 1913

Ink on paper

384 x 251 mm

Tate T00850

Presented by Kettle's Yard Collection, Cambridge 1966

Tate

Fig.13

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Wrestler 1913

Tate T00850

Tate

Another drawing in blue ink, Three Male Nudes Standing 1913 (Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris), echoes the swinging motion of the arms seen in Wrestler.19 While the two athletes on the right stand at rest, the man on the left stands with his legs further apart, swinging his arms with clenched fists as if he is about to throw a punch or has just flung an opponent. As with the drawing of the single wrestler, Gaudier-Brzeska uses a fine line to sketch out the contours of the bulges, dips and hollows of these toned bodies, their heads again compressed by the frame which Gaudier-Brzeska has drawn around the scene. Delicate diagonal hatching in blue ink gives bulk to the wrestlers. However, the poses and appearance of the figures represented in these two drawings are more closely related to Gaudier-Brzeska’s statuette The Wrestler than the later relief. As Evelyn Silber notes of Gaudier-Brzeska’s artistic output from his time in London: ‘While dating remains uncertain, it seems to be during the winter of 1912 and spring of 1913 that his figure studies, like his modelled and carved sculpture, became markedly more massive: the shoulders broadened and musculature more marked in the men.’20

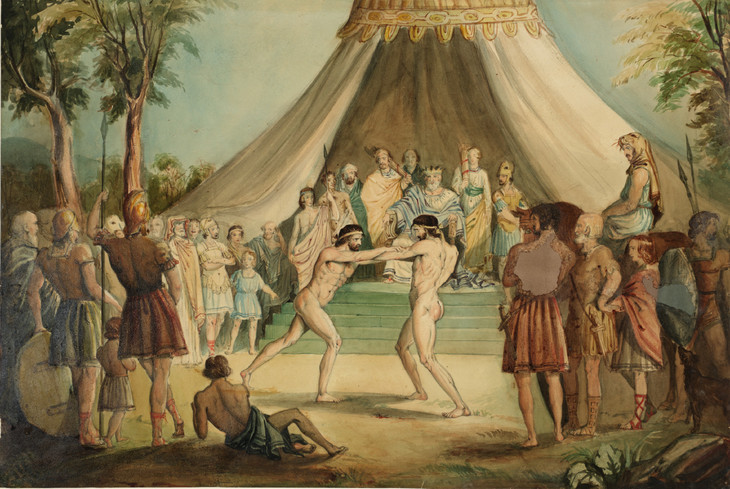

Sir John Everett Millais

The Wrestlers c.1840–1

Watercolour on paper

362 x 540 mm

Tate T00179

Presented by J T MacGregor-Morris 1958

Tate

Fig.14

Sir John Everett Millais

The Wrestlers c.1840–1

Tate T00179

Tate

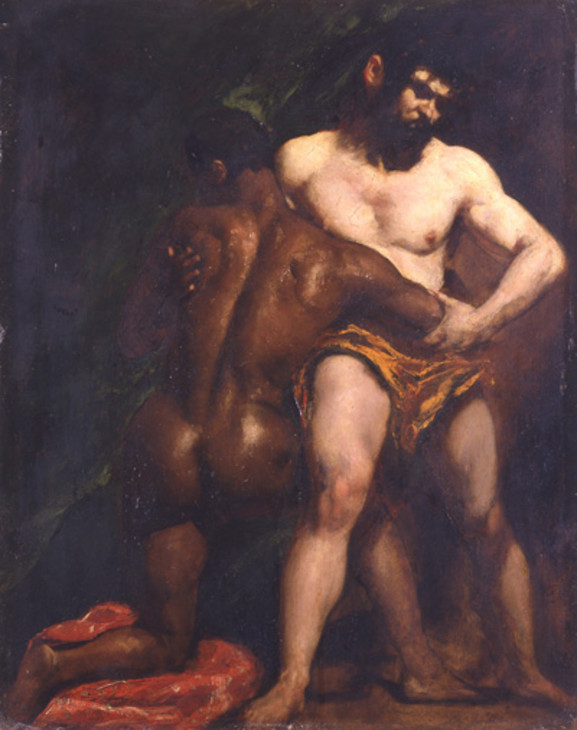

William Etty

The Wrestlers c.1840

Oil on millboard

685 x 533 mm

York Museums Trust

Fig.15

William Etty

The Wrestlers c.1840

York Museums Trust

Using wrestlers and pugilists as life models was common practice in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There are numerous sketches by such British artists as J.M.W. Turner, William Mulready, John Everett Millais and William Etty depicting wrestling figures drawn from life (see figs.14 and 15). Wrestlers, bodybuilders and boxers continued to make money as artist models in the twentieth century, and Gaudier-Brzeska’s life class was by no means unique in providing a wrestler for the pupils to draw. In an article in February 1913 in Health & Strength, Reginald Graham, a wrestler and an artist’s model, described the overlapping worlds of the gymnasium and the life class. Graham recounted how an art student ‘who surveyed me critically one evening at the gymnasium’ advised him to take up life modelling.21 It soon became apparent to the twenty-five-year-old Graham that he would have to pose for a nude photograph to send off to potential art schools along with his letter ‘intimating my readiness to sit as a model’. He described his first engagement in a well-known art school in north-west London (most probably St John’s Wood School of Art) as an ‘ordeal’ conducted under the critical collective gaze of the art students sat around the model’s platform in the life studio. But the physical demands of posing were not strenuous, Graham reported, and his gymnastic training had paid off as his body was manipulated into a series of poses and sequences.

In his article Graham laid bare the scopic process by which a model’s body was deemed suitable to draw. To interview for his next job at one of the largest art schools in London, Graham was invited to see the principal and put his body forward for examination. He wrote: ‘I was shown into a room and told to strip, and presently the principal came in. After he had seen my figure he promised me an engagement.’22 Graham recognised that there was a power dynamic at play in this transaction between life model and art school principal. Graham possessed the muscular power and physique, but it was the principal who had the power to approve whether it could be displayed in the life class, whether he had the right kind of figure. It was, Graham confirmed for his readers, good work for those who were prepared to travel and endure the whims of art masters and students. Throughout the article, however, there is also a trace of anxiety about his chosen profession. Graham highlighted the visual regime under which the life model operated. His naked body was constantly being looked at, more often than not by other men, under the hot lights of the life studio. Naked and exposed, Graham wrote of the ‘feeling that one undergoes a certain loss of dignity in becoming a figure model’.23 It is of course impossible to know how the wrestler that worked in Charles Wheeler’s office in the day and wrestled and posed at Gaudier-Brzeska’s life class at night – the one who was described by Gaudier-Brzeska as that ‘wonderful boy, strong, taut, and finely square’ – felt about his experience of showing off his muscles for the benefit of art students. Graham’s is a rare account, not only of the processes by which one became a life model, but also as a record of how he felt to be examined and observed. As Graham’s article makes clear, the move from the gym to the life class was an obvious one for a young man with a toned physique who, in 1913, wanted to make an income of about two pounds a week from life modelling. However, as he also stressed, the life class demanded its own strenuous routines that placed demands on the model both physically and psychologically.

Gaudier-Brzeska drew quickly, even urgently. At the life class he attended during the winter of 1912–13 he was perplexed by the slowness of the other people in the class. He could not understand why they would only produce two or three drawings in two or three hours. He wrote to Sophie that his drawing companions ‘think me mad because I work without stopping – especially while the model is resting, because that is much more interesting than the poses’.24 He worked quickly, but also productively, leaving each class with an astonishing amount of work. ‘I do from 150 to 200 drawings each time’, he told Sophie. The other life class attendees were obviously fascinated by this young French artist who drew with such intensity, and Gaudier-Brzeska was well aware that he intrigued them, commenting:

I work all during the two hours without a break in order to get my full six-pennyworth. They try to talk to me during the rests, but I don’t reply. Only when I have finished, if they speak to me I reply, and if they don’t, I just clear off, saying ‘good evening’’ [...] It is impossible for you to picture these asses.25

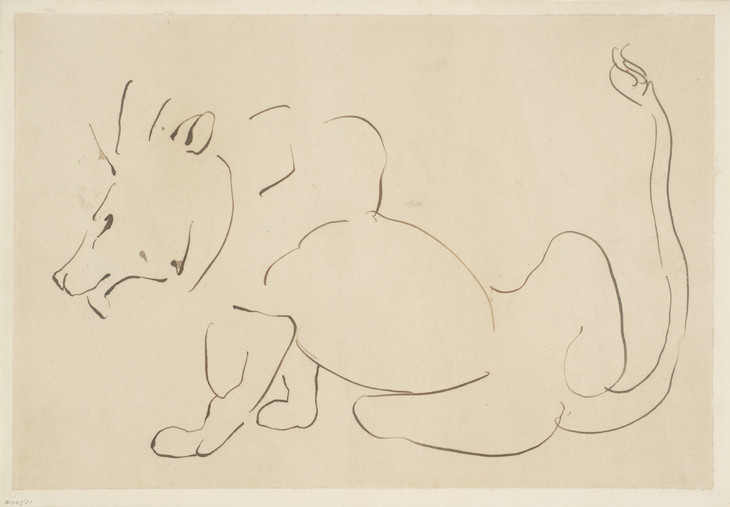

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Lion c.1912–13

Ink on paper

235 x 349 mm

Tate N04521

Presented by C. Frank Stoop through the Contemporary Art Society 1930

Tate

Fig.16

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Lion c.1912–13

Tate N04521

Tate

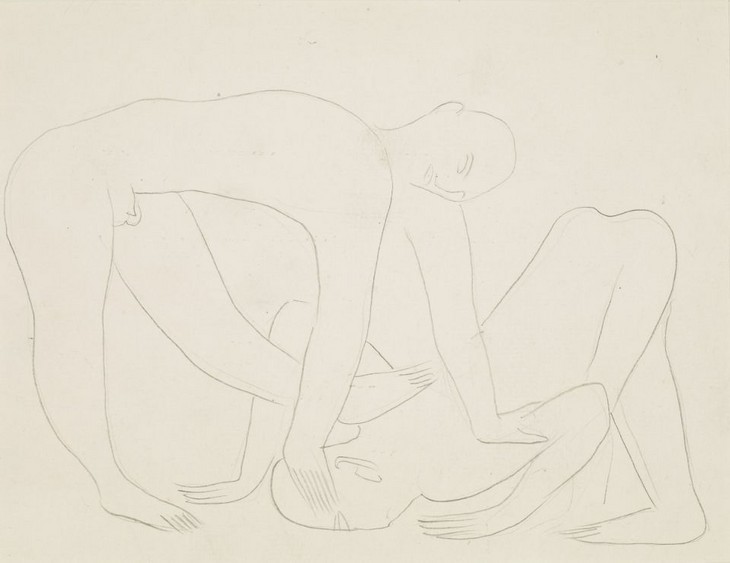

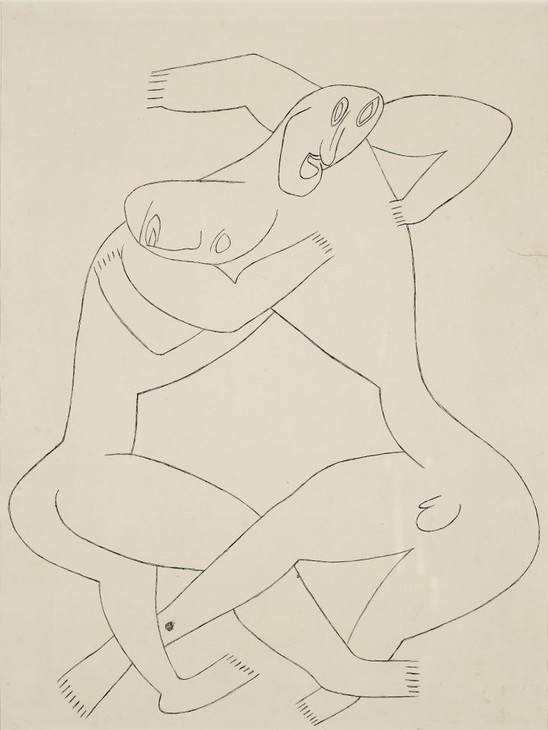

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Wrestlers c.1913

Graphite on paper

Photo: Kettle's Yard, Cambridge

Fig.17

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Wrestlers c.1913

Photo: Kettle's Yard, Cambridge

If all these drawings by Gaudier-Brzeska were only considered as preparatory drawings culminating in the Wrestlers relief, there is a risk that something of their importance would be missed, or that a timeline of production would be created that cannot actually be verified. As ‘preparatory’ studies the drawings are in danger of being seen as mere staging posts en route to the ‘finished’ sculpture. There are crucial interconnections between these drawings and the relief sculpture, which are more significant than one being ‘in preparation’ for the other. In fact, so prominent is the contour line of the wrestlers’ bodies in the Wrestlers relief, that it could be argued that this plaster sculpture is closer to two-dimensional drawing than three-dimensional sculptural practice. With the chisel, as with the pen, Gaudier-Brzeska carved a direct and unbroken line around the figures. Inside the contours there is little shaping or modelling, except for a few marks to shape eyes, mouths and hands. Even for his most well known piece of carving, the Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound 1914 (fig.18) Gaudier-Brzeska drew directly onto the stone to guide the force of his hammer hitting his chisel. With this in mind, Gaudier-Brzeska might even be said to have drawn with his chisel, such was the interconnectedness of drawing and sculpture in his work.

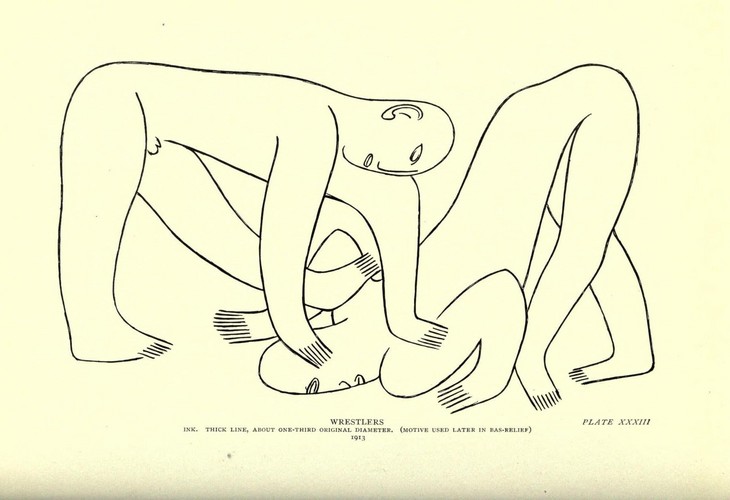

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska The Wrestlers reproduced in Ezra Pound, A Memoir of Gaudier-Brzeska, New York 1916, pl.33.

Fig.19

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska The Wrestlers reproduced in Ezra Pound, A Memoir of Gaudier-Brzeska, New York 1916, pl.33.

Notes

Francine A. Koslow, ‘The Evolution of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s “Wrestlers” Relief’, Museum Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, vol.78, 1980, p.42.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, letter to Sophie Brzeska, 28 November 1912, quoted in H.S. Ede, Savage Messiah, London 1931, p.209.

According to the art historian Paul O’Keeffe, Wheeler did not purchase Wrestler. Wheeler, O’Keeffe notes, probably intended the statues to be sporting trophies and ‘therefore needed to be no more than six or nine inches high, a fraction of the size Gaudier-Brzeska had produced’. Paul O’Keeffe, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska: An Absolute Case of Genius, London 2004, p.165.

W.A. Bridge, ‘Popular Clubs. No. III – The London Amateur Wrestling Society’, Health & Strength, 8 February 1913, p.142.

Michael Hatt, ‘Muscles, Morals, Mind, and the Male Body in Thomas Eakins’ “Salutat”’, in Kathleen Adler and Marcia Pointon, The Body Imaged: The Human Form and Visual Culture Since the Renaissance, Cambridge 1993, p.63.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Three Male Nudes Standing 1913 (Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris) http://www.centrepompidou.fr/cpv/ressource.action?param.id=FR_R-d221c531e6761eca70b040e5daa3d9d¶m.idSource=FR_O-efadc65a14132cf883c02d64b3d9af90 , accessed 3 July 2013.

Reginald Graham, ‘Experiences of an Artist’s Model’, Health & Strength, 8 February 1913, p.139. It is perhaps not too fanciful to imagine that the art student might have been Gaudier-Brzeska.

Gaudier-Brzeska, Two Wrestlers c.1913 (Centre Georges Pomipdou, Paris) http://www.centrepompidou.fr/cpv/ressource.action?param.id=FR_R-24f484bdd46cbcac9e52cfb2269da01d¶m.idSource=FR_O-f8141b1e1f3fd58f87fbbbb65ea94e , accessed 3 July 2013.

Deanna Petherbridge, ‘Nailing the Liminal: The Difficulties of Defining Drawing’, in Steve Garner (ed.), Writing on Drawing, Chicago 2008, p.37.

See also the comments made about the two drawings of Bird Swallowing a Fish c.1914, one in pencil and one in ink, on the Kettle’s Yard website: http://www.kettlesyard.cam.ac.uk/collection/work.php?work=395 , accessed 3 May 2012. Many thanks to Sebastiano Barassi for drawing my attention to this link.

How to cite

Sarah Victoria Turner, ‘Wrestling’, July 2013, in Sarah Turner (ed.), In Focus: 'Wrestlers' 1914, cast 1965, by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Tate Research Publication, July 2013, https://www