‘Suffer a Sea-Change’: Turner, Painting, Drowning

Sarah Monks

The artist J.M.W. Turner was able to suggest great depth and gravitational force in his depictions of seawater. Sarah Monks looks at the ways in which these qualities conveyed new forms of sublime experience.

‘Set or raised aloft, high up’; ‘Rising to a great height, lofty, towering’; ‘Exalted’; ‘Supreme’: by dictionary definition, ‘sublime’ signifies a state of elevation through which ascent towards physical or metaphorical heights brings about transcendence.1 ‘Go, fell the timber of yon’ lofty grove’, the poet Alexander Pope (1688–1744) had the Greek author Homer say in The Odyssey, ‘And form a Raft, and build the rising ship, / Sublime to bear thee o’er the gloomy deep’.2 Yet, as these lines suggest, ‘sublime’ (etymologically perhaps sub limen, up to a high threshold) always carries with it – even if only as trace memory – that over which it climbs or floats: ‘the gloomy deep’.

Pope quickly turned to this alternative site or state of ‘sub’ to which sublimity is umbilically attached but from which it had to be distinguished if transcendent achievement, poetic or otherwise, was to remain clear in an increasingly competitive world. He therefore set about defining this realm which lay beneath the sublime’s aerial firmament, a realm which reaches down into the depths and which is characterised by both dazzling material riches and mysterious profundities: ‘The Sublime of Nature is the Sky, the Sun, Moon, Stars, &c. The Profound of Nature is Gold, Pearls, precious Stones, and the Treasures of the Deep, which are [as] inestimable as unknown.’ In Pope’s satirical account (his tongue was firmly in his cheek here), these depths are the imaginary province to which the second-rate artist seeking wealth and patronage aspires, the decidedly sub par counterpart to those exalted heights of poetic sublimity at which their more talented and judicious colleagues arrive. Mediocre writers and painters therefore practise (Pope argued) an ‘Art of Sinking’, a descent into that jarring mixture of obscure nonsense and trivial or gaudy allusions which nevertheless seemed to represent poetic depth to the pretentious. By ‘keeping under Water’, the artist could therefore achieve precisely that over which the sublime soared: ‘the Bottom’ of his art.3 This is a wholesale revision of the ancient Greek term ‘bathos’, whose original reference to ‘depth’ remains in the technical terms for deep-sea diving equipment, the ocean bed and its measurement yet whose rhetorical formulation by Pope – as a ‘ludicrous descent from the elevated to the commonplace ... anticlimax’ – is now dominant.4 Seeking to consolidate an opposition between high and low, Pope’s ‘bathos’ is shot through with its divisive social implications, which find form in the fictive poetic examples – among them the lady who acts like a street hawker and the footman who speaks like a prince – with which he illustrates his account.5

By engaging with the implications of ‘beneath’, of the sub- in the sublime, this article sets out to challenge any sense of the sublime as necessarily already ascendant, as always and easily cut free from its murky remnant. In particular, this article will focus on the ways in which J.M.W. Turner set about suggesting, to an extent which is unprecedented in the visual representation of water, what it might be to be beneath – beneath the horizon, beneath the water and beneath paint. The broader implications of this ‘submarine’ state for the forms of subjectivity at stake in Turner’s work will be hinted at towards the end but, by way of instructive analogy, I want to begin with a metropolitan site which was all but given over in the early nineteenth century to the idea that paintings and people speak from the deep, in a process which seemed to conjure both the sublime and the subliminal.

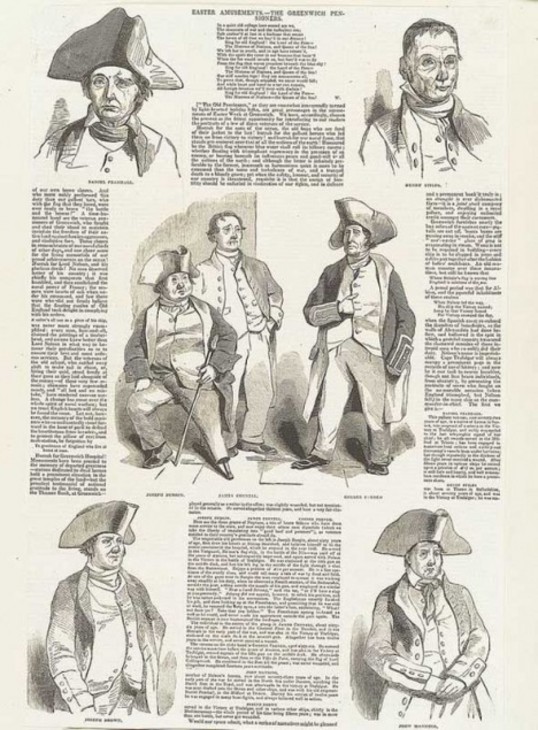

Easter Amusements – The Greenwich Pensioners … (with biographical details on each) The Illustrated London News 13 April 1844, p.233

Photo © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Fig.1

Easter Amusements – The Greenwich Pensioners … (with biographical details on each) The Illustrated London News 13 April 1844, p.233

Photo © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Every blue-jacket [that is, every old sailor], may now ... reclaim from oblivion some anecdote of courage or of kindness. An attentive public, in listening to the unaffected strain, will learn to respect the knowledge displayed, and the generous effusions of a brave man’s heart ... From such observations a candid and judicious artist may learn how to improve his compositions: why some pictures ... fail to call forth the feelings of an unsophisticated public; whilst ... one of rude aspect, may kindle all the outward expression of deep-rooted sympathy.

The impact of such Pensioner soliloquies would therefore be perceived not only ‘in the improved taste ... and in the improved feelings’ of that ‘attentive public’ but also in the output of contemporary artists who, listening to the sailor’s ekphrastic recovery ‘from oblivion’ of past officer-class merit, might ‘learn how to improve his compositions’ so that they appealed to the better sentiments of plebeian audiences.7 Moreover, by inhabiting a public exhibition space aimed at the articulation of conservative ideals to an audience of increasingly – and, to some minds, worryingly – socially enfranchised urban day-trippers, painting was made to illustrate self-sacrifice in the name of a greater good. Only then, Clarke claimed, are ‘the arts of peace’made to put forth their best energies – to shed their lustre on the history of a nation’s bravest sons, and tempt the early germs of enthusiasm to rivalry with past greatness. This is the proper application of the art of painting.8

That medium appeared at Greenwich as a means of redressing the apparently diminished role of both élite example and popular heroism in a railway age, as a proactive presence capable of working its magic upon the political and moral sensibilities of its viewers decades, even centuries, after its own production.9 For Clarke (and he was merely echoed by the Naval Gallery’s other commentators), painting’s ‘proper application’ was to instantiate a past greatness that might thereby be raised up, resurfacing in the present to powerful (if reactionary) social and cultural effect.

This sense of painting’s ability to transcend the impact of change and the stark temporal difference wrought by modernity referenced the broader reconception of art’s powers which had been elaborated in aesthetic theory since the late eighteenth century. There, art had increasingly been deemed capable of challenging the distance not only between past and present but also between seeing and feeling.10 Furthermore, by the time that Clarke put pen to paper in the 1840s, the notion that both painters and their paintings might have such transformative effects on their viewers had come to be associated in particular with the works of one artist: Turner.

That medium appeared at Greenwich as a means of redressing the apparently diminished role of both élite example and popular heroism in a railway age, as a proactive presence capable of working its magic upon the political and moral sensibilities of its viewers decades, even centuries, after its own production.9 For Clarke (and he was merely echoed by the Naval Gallery’s other commentators), painting’s ‘proper application’ was to instantiate a past greatness that might thereby be raised up, resurfacing in the present to powerful (if reactionary) social and cultural effect.

This sense of painting’s ability to transcend the impact of change and the stark temporal difference wrought by modernity referenced the broader reconception of art’s powers which had been elaborated in aesthetic theory since the late eighteenth century. There, art had increasingly been deemed capable of challenging the distance not only between past and present but also between seeing and feeling.10 Furthermore, by the time that Clarke put pen to paper in the 1840s, the notion that both painters and their paintings might have such transformative effects on their viewers had come to be associated in particular with the works of one artist: Turner.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Fishermen at Sea exhibited 1796

Oil paint on canvas

support: 914 x 1222 mm; frame: 1120 x 1425 x 105 mm

Tate T01585

Purchased 1972

Fig.2

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Fishermen at Sea exhibited 1796

Tate T01585

‘As a sea-piece this picture is effective’, declared one critic, in a phrase which explains the work’s impact on the one hand and damns with faint praise on the other.15 For this was a genre which seemed to be practised only by artists who had (in the words of another) ‘too servilely followed the steps of each other, and given us Pictures more like japanned tea-boards, with ships and boats on a smooth and glassy surface, than adequate representations of that inconstant, boisterous and ever changing element’.16 Only Turner seemed to his commentators to have recognised the sea’s redesignation in contemporary culture as a space where, par excellence, transcendent mastery might be realised, and where the real extent of one’s physical, moral and aesthetic responsiveness might be revealed. As the Naval Chronicle (not a publication ordinarily given to philosophical enquiry) would put it in the 1790s, the sea appeared to its viewers only as it exists in the mind of the beholder: if he does not possess a soul sufficiently enlarged to feel the sublimity and endless variety of such a scene, he should daily endeavour to awaken a sense within him, which either the force of habit has closed, or the want of a discriminating taste has never called forth.17

Through such statements (and students of literary romanticism will know they are not hard to find during this period), the sea was emphatically assigned the status of testing ground for a self able to convert the world into indicative sensual experience. At once deeply material and dematerialised, both ‘boisterous element’ and something existing ‘in the mind of the beholder’, the sea’s depiction presented Turner with distinct challenges, among which was the potential capacity of one possessed with ‘genius and judgment’ to revive a moribund pictorial genre as the grounds for an ‘effective’ art of aesthetic invention and experiment.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Shipwreck exhibited 1805

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1705 x 2416 mm; frame: 2085 x 2795 x 235 mm

Tate N00476

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.3

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Shipwreck exhibited 1805

Tate N00476

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth exhibited 1842

Oil paint on canvas

support: 914 x 1219 mm; frame: 1233 x 1535 x 145 mm

Tate N00530

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.4

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth exhibited 1842

Tate N00530

Exhibited as ‘Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth making Signals in Shallow Water, and going by the Lead. The Author was in this Storm on the Night the Ariel left Harwich’, this painting makes explicit claims (in its image and in its title) to first-hand experience. As so often in Turner’s work, that experience is one in which nature and human culture work across and against each other. In its confrontation with raw unassailable forces beyond human determination, that culture’s attempts to organise and cut through the world in its own interests (courtesy of engines, boats and straight-ahead navigation) are cast as a hubris familiar from ancient mythology. And in his desperate attempt to remain upright and proceed through space on his own terms – that is, to resist being stilled, swallowed and negated – man burns out both himself and his resources, the overworked engine that drives the boat’s thrashing wheel leaving a foul scorchmark across the sky. There, even the systematisation of the visual into language appears futile, the boat’s distress signal appearing little more than a transient spectacle already most clearly figured by its own feeble remnants: a rocket and red cinders falling, like Icarus and his feathers, into the sea.25 The vessel’s crew (indicated perhaps by a figure who reaches down to the water from directly beneath the mast) ‘go by the lead’, plumbing the depths in order to gauge their proximity to the bottom and to death.

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Sun of Venice Going to Sea exhibited 1843

Oil paint on canvas

support: 616 x 921 mm; frame: 872 x 1178 x 115 mm

Tate N00535

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.5

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Sun of Venice Going to Sea exhibited 1843

Tate N00535

In a painting which highlights the readiness of its ‘Author’ to find himself adrift from his cultural inheritance, compelled to devise his own pictorial materials, language and forms whilst exercising his own criteria about their use, it is significant that the resulting image depicts not a scene of clear departure or arrival but rather a moment out at sea and mid-voyage. Snow Storm is about artistic process (‘making Signals’) rather than product; indeed, it seems to be a signal fired off from the very midst of painting. What Turner reveals himself to have been caught up in here is therefore less the agonies involved in taking leave of tradition (or those of establishing the new) than the full whiteout of art itself, away from its ports of call.32

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Peace - Burial at Sea exhibited 1842

Oil paint on canvas

support: 870 x 867 mm; ;

Tate N00528

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.6

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Peace - Burial at Sea exhibited 1842

Tate N00528

He was, after all, an artist who apparently wanted to be buried in one of his pictures, and whose Royal Academy exhibits in 1842 included both this painting and Peace – Burial at Sea (fig.6), two works which between them triangulate painting, drowning and death.34 The purported subject-matter of Snow Storm implies the costs of such a voyage into the unknown: the possibility of a disaster which can only be kept at bay by the careful and constant monitoring of one’s proximity to the seabed, a perfect metaphor for the self-reflective, self-scrutinising methods of the artist, and indeed the individual, within modernity. Estranged from the safe havens of established convention by conspicuous historical change, the (artistic) subject was now obliged or liberated – Turner would have it both ways, practising a melancholic exuberance into old age – to travel under their own steam.

Read as an image of culture in tension with nature or as an allegory of artistic originality, Snow Storm shows Daedalus’s realm of human ingenuity and creation at once assaulted and reasserted. But his is not the only mythology conjured by this picture of tempest. In a veiled reference to the recent disaster of the Fairy (which had left Harwich in November 1840, sinking with all hands shortly afterwards), Turner’s title conjures the malign sprite Ariel from Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest.35 Turner’s evocation of this play is more than passing fancy or allusion.36 For, in his most significant intervention into the narrative, Ariel whispers into the ear of shipwrecked Ferdinand a beautiful lie about drowning:

Full fathoms five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.37

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.37

In Ariel’s song, Ferdinand’s father Alonso survives his drowning in mutated form, having been transformed into something ‘rich and strange’ courtesy of a merger with his new environment. Alonso has not vanished or faded but rather has undergone a liquefying ‘sea-change’, his difference from his surroundings diluted to the point that his body has become (in the words of the literature theorist Ian Baucom) ‘a catalog of the things that wash over it’, a body of work.38 As a figure for art’s capacity to deceive and delight, ‘Ariel’ also refers us back to Turner’s status as artist and, perhaps, to the sea itself, which appears in painting and play alike as a space of deception and artifice,39 reaching out like the sailor’s tropical delirium ‘calenture’ to challenge settled distinctions between high and low, art and sinking.40

Notes

‘sublime, a. and n.’, Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, http://www.oed.com accessed 20 April 2010.

Homer, The Odyssey of Homer, trans. Alexander Pope, Elijah Fenton and William Broome, 5 vols., vol.2, London 1725–6, p.14.

‘Martin Scriblerus’ [Alexander Pope], ‘Peri Bathous: or The Art of Sinking in Poetry’, in Jonathan Swift, and Alexander Pope, Miscellanies in Prose and Verse, second edition, 2 vols., vol.2, Dublin 1728, pp.91–2.

See ‘bathy-’ and ‘bathos’, Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, http://www.oed.com accessed 20 April 2010. See Freya Johnston, Samuel Johnson and the Art of Sinking 1709–1791, Oxford 2005, on Johnson’s ironic deployment of Pope’s ‘bathos’.

Henry G. Clarke, The Naval Gallery, with a Description of the Painted Hall and Chapel, London 1842, p.v.

Clarke, The Naval Gallery, pp.v–vii. Such scenes gained extra weight after 1841, when the gallery was opened free of charge to all sailors every day, and then to the general public on Mondays and Fridays: see Report from Select Committee on National Monuments and Works of Art, London, 16 June 1841, pp.v–vi, in House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:hcpp&rft_dat=xri:hcpp:rec:1841-019573 accessed 18 March 2009, and The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction, vol.2, no.4, 23 July 1842, p.64. See Brandon Taylor, Art for the Nation: Exhibitions and the London Public, 1747–2001, Manchester 1999, pp.29–66, on contemporary debates about opening national collections to the general public.

The city’s first passenger train line, the London and Greenwich Railway, had begun to deliver its (many thousands of) passengers on day trips from central London in 1838: see Clive Aslet, The Story of Greenwich, London 1999, pp.246–55.

See Gavin Budge (ed.), Aesthetics and the Picturesque, 1795–1840, 6 vols., Bristol 2001; Jonah Siegel, Desire and Excess: The Nineteenth-Century Culture of Art, Princeton 2000; Paul Mattick Jr, Eighteenth-Century Aesthetics and the Reconstruction of Art, Cambridge 1993, and Stephen Copley and John Whale eds., Beyond Romanticism: New Approaches to Texts and Contexts, 1780–1832, London and New York 1992.

Though one critic thought that the painting ‘would have borne a brighter situation’: London Packet or New Lloyd’s Evening Post, 27 April 1796.

See Companion to the Exhibition, quoted in Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, second edition, 2 vols., New Haven 1984, vol.1, no.1.

London Packet or New Lloyd’s Evening Post, 27 April 1796, in a line that begins, ‘Considered as a study from Nature, or a design on the principles of Nature...’ For comments about Turner’s anonymity in 1797, see The Morning Post, 5 May 1797 and Thomas Green, The Diary of a Lover of Literature, 1810, p.35. One critic knew of him, recognising that (having been a draughtsman) he had ‘strayed from the direct walk of his profession’ in painting seascapes: The Times, 3 May 1797. See Butlin and Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, no.3.

London Packet or New Lloyd’s Evening Post, 27 April 1796; Companion to the Exhibition, London, 1796, and ‘Anthony Pasquin’ [John Williams], A Critical Guide to the Present Exhibition of the Royal Academy for 1796, London, 1796, quoted in Butlin and Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, no.1.

‘Anthony Pasquin’ [John Williams], A Critical Guide to the Present Exhibition of the Royal Academy for 1797, London 1797, pp.10–11.

Naval Chronicle, vol.1, 1799, p.208, quoted in John Gage, ‘Turner and the Picturesque – I’, The Burlington Magazine, vol.107, no.742, January 1965, p.9.

See The Wreck Buoy (c.1807 and 1849, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool; Butlin and Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, no.428), and Helvoetsluys; – the City of Utrecht, 64, going to Sea (1832, private collection; Butlin and Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, no.345).

See The Shipwreck 1805, Tate, The Wreck of a Transport Ship c.1810, Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, and Entrance of the Meuse 1819, Tate (Butlin and Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, no.139).

See Boats Carrying Out Anchors and Cables to Dutch Men of War, in 1665 1804, Corcoran Art Gallery, Washington DC.

See Fishermen upon a Lee-Shore in Squally Weather 1802, Southampton City Art Gallery and Sun Rising through Vapour; Fishermen Cleaning and Selling Fish 1807, National Gallery, London (Butlin and Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, no.69) and Port Ruysdael 1827, Yale Center for British Art.

See Helen Guiterman, ‘“The Great Painter”: Roberts on Turner’, Turner Studies, vol.9, no.1, Summer 1989, p.6.

See Brian Lukacher, ‘Turner’s Ghost in the Machine: Technology, Textuality, and the 1842 Snow Storm’, Word & Image, vol.6, no.2, April–June 1990, pp.119–37.

See Gilles Deleuze, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, London and New York 2006, and Darren Ambrose and Wahida Khandker, (eds.), Diagrams of Sensation: Deleuze and Aesthetics, Coventry 2005.

See Rosalind Krauss, Bachelors, Cambridge MA 1999, pp.7–8, on Bataille’s concept of alteration as ‘both decomposition (as in corpses) and the total otherness of the sacred (as in ghosts)’, and associated with formless subjects and images. The rapid and alternating movement between different states set in motion by Turner’s seascapes was complemented by a contemporary critical consensus that his was an art which polarised public opinion and was itself by turns glorious and shameful (see, for example, the review of his Royal Academy exhibits in The Examiner, 7 May 1842, and Jerrold Ziff, ‘William Henry Pyne’s “J.M.W. Turner, R.A.”: A Neglected Critic and Essay Remembered’, Turner Studies, vol.6, no.1, 1986, pp.18–25).

Cf. the early nineteenth-century interest in sea-sickness and the effects of dramatic rotation, elevation and descent upon the human brain. See Nicholas J. Wade and U. Norrsell, ‘Cox’s Chair: ‘A Moral and a Medical Mean in the Treatment of Maniacs’, History of Psychiatry, vol.16, no.1, 2005, pp.73–88 on the related rotating centrifugal chairs devised by Erasmus Darwin and Joseph Mason Cox as treatments for the insane in the first decade of the nineteenth century.

See Jörg Traeger, ‘“... As if one’s Eyelids had been Cut Away”: Imagination in Turner, Friedrich, and David’, in Frederick Burwick and Jürgen Klein (eds.), The Romantic Imagination: Literature and Art in England and Germany, Amsterdam 1996, pp.413–34, and Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, Cambridge MA and London 1990, p.139.

See Lukacher, ‘Turner’s ghost’, p.122: ‘It was the artist’s unique responsiveness to the scene, not the presumed actuality of the scene, that was paramount ... This was a painter’s painting, the drama enacted more at the easel than at the mast.’

On Turner’s sketching practice as ‘an embodiment of the act of thinking’, see Andrew Wilton, Turner as Draughtsman, Aldershot 2006, pp.78–81.

See Butlin and Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, vol.1, pp.94–6 for contemporary anecdotes concerning the artist’s express wish that his Dido Building Carthage; or The Rise of the Carthaginian Empire 1815, (National Gallery London) should be his burial shroud.

On Turner’s birthday, see Sam Smiles, ‘Turner: Space, Persona, Authority’, in Dana Arnold and Joanna Sofaer (eds.), Biographies and Space: Placing the Subject in Art and Architecture, London 2008, p.111. For examples of Turner’s Shakespearean subjects, see What You Will! 1822 9 Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown MA), Jessica (1830, Petworth, National Trust), Juliet and her Nurse 1836 (private collection), The Grand Canal (‘Scene – A Street in Venice’) 1837 (The Huntington Library, San Marino, California), as well as the sketches from his visit to Shakespeare’s monument and Stratford circa 1833–6 (Wilton 1101 and Finberg CCXCIII, Tate).

William Shakespeare, The Tempest, ed. by Alden T. Vaughan and Virginia Vaughan, London 1999, Act 1, Scene 2.

Ian Baucom, ‘Hydrographies’, The Geographical Review, vol.89, no.2, April 1999, p.303. See also the discussion of Jackson Pollock, Sea Change and Full Fathom Five 1947 (Seattle Art Museum and MoMA, New York respectively), in T.J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, New Haven and London 1999, pp.299–305.

See Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Oxford and New York 1990, p.70: ‘No work of art can be great, but as it deceives’. The ‘genius’ and ‘mysterious effect’ of Turner’s work had long been understood to be the ‘effect of magic’ produced by ‘this Prospero of the graphic art’: Repository of Arts, June 1812, quoted in Kay Dian Kriz, The Idea of the English Landscape Painter: Genius as Alibi in the Nineteenth Century, New Haven and London 1997, p.1. See also Lukacher, ‘Turner’s Ghost’, pp.128–35.

Since the seventeenth century, the sailor had been thought peculiarly prey to ‘calenture’, a tropical delirium in which he ‘with rapture sees, on the smooth ocean’s azure bed, Enamell’d fields and verdant trees’ (Jonathan Swift, The Bubble: A Poem (Upon the South Sea Project), London 1721, p.vii). Described as a medical condition in early eighteenth-century medical texts such as John Moyle’s Chirurgus Marinus: Or, the Sea-Chirurgien, London 1702, p.226, ‘calenture’ continued to be invoked into the late nineteenth century as a figure for any delirious or drunken passion (see, for example, ‘The Wishing-Cap’, The Examiner, 28 March 1824). Cf. The Spectator, October 1840, p.957 on Turner’s ‘diseased fancies’; ‘the phrensy or delirium under which he labours is only an over-excitement of the sensorium’; quoted in Luckacher, ‘Turner’s Ghost’, p.122).

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this text was delivered at the conference The Sublime in Crisis? New Perspectives on the Sublime in British Visual Culture 1760–1900, held at Tate Britain in September 2009.

An earlier version of this text was delivered at the conference The Sublime in Crisis? New Perspectives on the Sublime in British Visual Culture 1760–1900, held at Tate Britain in September 2009.

Sarah Monks is Lecturer in European Art History, School of World Art Studies and Museology, at the University of East Anglia.

How to cite

Sarah Monks, ‘‘Suffer a Sea-Change’: Turner, Painting, Drowning’, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013, https://www