The Sublime in Crisis: Landscape Painting after Turner

Alison Smith

In the latter half of the nineteenth century some artists abandoned the pursuit of the sublime for reasons of taste, others because of an increased interest in beauty and scientific realism. Nevertheless, as Alison Smith writes, the sublime still held great importance for many Victorian artists, even as they distanced themselves from the sublime of the Romantic era.

This essay examines the various ways in which British landscape painters engaged with concepts of the sublime in the second half of the nineteenth century. In the visual arts the sublime tends to be associated with the period of roughly 1750–1850 when a new emotional response to landscape first developed in the work of Romantic painters, and found full expression in the art of J.M.W. Turner. The general view is that the term lost its former currency after 1850 due to a shift in aesthetic and cultural values, and that it gave way to beauty as the most compelling aesthetic ideal.1

This essay considers why the sublime should have fallen out of favour in intellectual circles, using this as the background to examine various ways in which artists continued to engage with the concept in landscape painting during this so-called recessive period. Because so little published material exists on the idea of the sublime in the Victorian period, this essay takes the form of case studies of works in the Tate collection to pose questions about the category. Although this approach might be regarded as restrictive in not allowing for a central narrative, the heterogeneity of the chosen examples does enable coverage of the principle areas in which the subject manifested itself in British landscape painting. The test cases show that although the sublime may have been in crisis, it nevertheless continued to have an impact in multifarious ways. While these ways might be regarded as marginal to mainstream artistic tendencies, they are too important to be overlooked, especially as they engage with contemporary social, scientific and cultural developments.

I start by asking if there was something peculiar to the aesthetic ideals which predominated in the mid-nineteenth century that caused the sublime to drop out of circulation, and then proceed to look specifically at the Pre-Raphaelite landscape, at works which ostensibly eschewed the visual rhetoric of the sublime out of a concern for objectivity and ‘truth’, but which at the same time offered new ways of harmonising analysis with symbolism in confronting themes such as judgement, vastness, transcendence and terror, all traditionally regarded as manifestations of the sublime. In the second part of the essay I look at the return to ‘affect’ – the explicit appeal to emotion through expressive painterly means – in the later nineteenth century, at works which seem to signal a revisiting of the Romantic and Turnerian models of the sublime but within a more troubled theological framework informed by the spirit of agnosticism that followed in the wake of the evolutionary theories advanced by Charles Darwin, and that in some cases can be regarded as a visual parallel to the art critic John Ruskin’s notion of the grotesque.

Burke’s sublime

Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) continued to be the central text for the sublime in Britain during the nineteenth century. In this work Burke explored the sublime in terms of physiologically related responses to phenomena, referring to it as an instinct of self-preservation:

Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the idea of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling ... When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances, and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are delightful, as we every day experience.2

For Burke the main causes of the sublime were darkness, obscurity, privation or vastness – qualities he associated more with terror than elation. On the continent, Immanuel Kant’s interpretation of the sublime dominated. This differed from Burke’s theory in focusing more on the concept as a mental condition, or an aesthetic experience that emerged from a strain in perceiving something boundless or infinite. While Kant appreciated the usefulness of Burke’s approach he felt a definition that depended on the sensations of individuals was too empirically based to lead to any satisfactory explanation of how the sublime functioned.

Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry raises a number of issues for the period in question. First, the extent to which the associative nature of the sublime goes against the innate character of painting. Second, there is the problem of the association of the sublime with fear rather than elation. Both these issues would seem to militate against the mainstream use of the sublime in relation to the art of the later nineteenth century where the principle directions would appear to be a realism defined in terms of particular, clearly articulated forms or an idealism focused on pure beauty as seen in the classical and aesthetic styles that emerged after 1860 which aimed at eliciting disinterested rather than disturbed emotion in the beholder. In these circumstances the Burkean sublime could be seen as an ‘other’ that continued to have an impact but arguably more in the field of popular culture, theatrical entertainment and illustration than in fine art.

Turner’s sublime

Any discussion of the sublime in the second half of the nineteenth century should start with Turner. Of all Romantic painters influenced by the aesthetic of the sublime, his works have been widely recognised as the most successful in capturing the effect of boundlessness which Burke and Kant saw as a prerequisite for the sublime in verbal and visual representation – the sublime being something that can be evoked but not achieved.3 Those works by Turner typically seen as sublime employ a formal language that avoids precise definition, instead using paint to hint at the terrifying and awesome but on a relatively modest scale when compared to the bombastic productions of painters such as Francis Danby and James Ward. Through juxtapositions of dark and light, obtrusive facture and subtle blending effects, combined with energetic centrifugal and vortex configurations and exaggerated distortions of scale, Turner’s works have been seen to both elevate and inspire perception in the beholder.

This view owes much to John Ruskin’s championing of the artist in his book Modern Painters. Ruskin was the most important English art critic of his time with a career spanning almost the entire reign of Queen Victoria. Because he was such a prolific writer – the standard edition of his works amounts to thirty-nine volumes – his criticism is useful for calibrating the shifts in aesthetic judgement that took place during the period. A figure of quasi-biblical authority in his own day, Ruskin was one of the first critics to write about art with poetry and feeling, and it was the unprecedented intensity of the language he used to evoke the sublime that helped elevate the status of art criticism in British writing. In particular, it was the force and conviction with which Ruskin relayed what he felt to be the sublime pessimism of Turner’s art that influenced subsequent opinion about the greatness of the artist’s work, overcoming contemporary objections that his abstract compositions appeared incomprehensible, even ridiculous, like soap or treacle.4 One could even go so far as to argue that it was Ruskin who made Turner sublime by rescuing the visual from itself and returning it to language.

In his Philosophical Enquiry Burke emphasised literary forms, especially poetry, as more capable of expressing the sublime than the visual arts, projecting the sublime as an idea that only the verbal could evoke:

The images raised by poetry are always of this obscure kind ... But painting, when we have allowed for the pleasure of imitation, can only affect simply by the images it presents; and even in painting a judicious obscurity in some things contributes to the effect of the picture; because the images in painting are exactly similar to those in nature; and in nature dark, confused, uncertain images have a greater power on the fancy to form the grander passions than those have which are more clear and determinate.5

Ruskin’s writings on Turner appear to support Burke in suggesting that the word is more successful in evoking the sublime because it is so radically different from what it seeks to describe, whereas the visual image, while having greater potential to represent forms which give rise to the experience of the sublime, risks collapse at the point of expression. The paradox of the visual is thus that it offers the promise of realising the sublime, aspiring to bridge the gap between language and translation, but at the risk of descending into banality, formula or illustration.

One of the most celebrated passages in Ruskin’s writings is his ekphrasis, or literary description of a work of art, on Turner’s Slave Ship or Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On 1840 (fig.1), in which metaphor and simile are taken to extremes, allowing Ruskin to repaint the scene in words. Thus he could vicariously involve the spectator in the drama and convey the idea of nature as a vehicle of divine judgement:

Purple and blue, the lurid shadows of the hollow breakers are cast upon the mist of night, which gathers cold and low, advancing like the shadow of death upon the guilty ship as it labours amidst the lightning of the sea, its thin masts written upon the sky, in lines of blood, girded with condemnation in that fearful hue which signs the sky with horror and mixes its flaming flood with the sunlight, and, cast far along the desolate heave of the sepulchral waves, incardines the multitudinous sea.6

Although this passage acknowledges the Burkean sublime – the experience of terror and awe induced by the description eliciting an intense emotional response in the reader – it was published in the first volume of Modern Painters (1843) in which Ruskin also explicitly rejected the sublime as a discrete category:

Anything which elevates the mind is sublime, and elevation of mind is produced by the contemplation of greatness of any kind ... Sublimity is, therefore, only another word for the effect of greatness upon the feelings – greatness, whether of matter, space, power, virtue, or beauty: and there is perhaps no desirable quality of a work of art, which, in its perfection, is not, in some way or degree, sublime.7

As the scholar George Landow has explained, since Ruskin believed the perception of beauty was a moral, even a religious act, he could not accept the depreciation of the beautiful implied by Burke’s opposition of it to the sublime even though he respected the main parts of Burke’s thesis, namely that the sublime was concerned with greatness, that it was a matter of emotion and that it related to religion or the idea of the holy.8

By 1853 Ruskin had shifted his position to accept the sublime as a separate aesthetic category that related to the experience of awe and terror, but he still struggled with the Burkean notion of ‘terrible sublimity’, maintaining that a susceptibility to terror was a sign of religious doubt, even atheism. Ruskin’s acknowledgment of ‘terrible sublimity’ can thus be seen as an indication of his difficulty in understanding nature on a theological basis, especially as he focused his analysis of the sublime in terms of its effect on the beholder. If the sublime was not a manifestation of divine power and moral judgement working through nature, it risked being merely horrid, incapable of elevating the mind or the imagination. On a personal level, as his faith wavered towards the end of the 1850s, Ruskin found himself overwhelmed and depressed by ‘the cruelty and ghastliness of the Nature I used to think so sublime’.9 His solution to the problem of salvaging any sense of moral awareness from the sublime was to evolve the concept of the ‘grotesque’ or the ‘symbolic sublime’ in the third volume of Modern Painters (1856). Recognising that the sublime was beyond representation, Ruskin felt it could be recognised in part through symbols or the fragmented and disordered images that accompany but do not in themselves constitute greatness.10

Pre-Raphaelitism and the anti-sublime

Ruskin’s oscillating views on the sublime offer one important route into our exploration of how the topic was expressed in visual terms in the latter half of the nineteenth century, particularly in helping us to understand the difficulties artists had in articulating and expanding the Romantic sublime as it had developed up to the time of Turner.11

According to the scholar Morton Paley, the apocalyptic sublime was a mode that flourished during a period of domestic unrest and foreign wars. It was a means of displacing into art the political and social dislocations produced by the turbulence of that era, as well as expressing the fervent religious evangelical belief that came to be challenged later in the century.12 However, apocalyptic imagery continued to dominate throughout the Victorian period, in dioramas and panoramas and in what have been regarded as the populist landscapes of John Martin. Martin’s immense triptych The Last Judgement 1851–3 (Tate N05613, T01928 and T01927) was one of the major works that astonished the public in the years immediately after Turner’s death, and continued touring until the 1870s. It was shown in New York in 1856 to great acclaim where it fuelled the ‘American Sublime’ as seen in the art of landscape painters such as Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt whose works were well known in Britain. The sublime also continued to make its presence in regional landscape painting, particularly in Wales and Scotland, notable exponents of the genre including Henry Clarence Whaite and Horatio MacCulloch. Beyond Britain the Romantic sublime flourished on the periphery of the British Empire and was often employed to represent unfamiliar subjects, as in Edward Lear’s Kinchinjunga from Darjeeling, India of 1879 (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven).

However, it would be true to say that by the middle of the century a new aesthetic was in the ascendant. The year 1851 can be seen to represent a watershed regarding the sublime. The demise of its two great exponents in literature and art – Wordsworth in 1850 and Turner in 1851 – has been taken to represent the passing of a sublime moment in British culture. The failure of the Chartist uprisings of 1848 to have any lasting effect, and the spirit of confidence and prosperity generated by the Great Exhibition of 1851, have suggested to historians that a spirit of equipoise or balance between the claims of the past and the forces of modernity dominated the mid-Victorian period, negating any need for such an extreme aesthetic form as the sublime.

J.M.W. Turner

Rain, Steam and Speed 1844

The National Gallery, London

Photo © The National Gallery 2011

Fig.2

J.M.W. Turner

Rain, Steam and Speed 1844

The National Gallery, London

Photo © The National Gallery 2011

The challenges presented by science, religious doubt and positivist philosophy which accompanied the shift to an urban secular society, informed, in turn, the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic. Pre-Raphaelite painters set out to valorise the familiar and everyday in a spirit of reaction to the artificiality and elitism of the Romantic sublime, which they felt had descended into pictorial cliché in the work of contemporary academic painters. A similar ‘democratic’ approach underpins the novels of George Eliot, who was influenced by developments in landscape sensibility through the work of Ruskin and the cult of detailed naturalism espoused in Pre-Raphaelitism. In Adam Bede (1859) Eliot writes:

In this world there are so many of these common coarse people ... It is so needful we should remember their existence, else we may happen to leave them quite out of our religion and philosophy and frame lofty theories which only fit a world of extremes. Therefore, let Art always remind us of them; therefore let us always have men ready to give the loving pains of a life to the faithful representing of commonplace things – men who see beauty in these commonplace things, and delight in showing how kindly the light of heaven falls on them. There are few prophets in the world; few sublimely beautiful women; few heroes.14

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt 1829–1896

The Order of Release 1746 1852–3

Oil on canvas

support: 1029 x 737 mm; frame: 1505 x 1210 x 125 mm

Tate N01657

Presented by Sir Henry Tate 1898

Fig.3

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt

The Order of Release 1746 1852–3

Tate N01657

In light of this sort of comment it is possible to detect a trajectory in the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic that can be described as ‘anti-sublime’. By comparing the landscapes painted by artists such as Hunt, John Brett and J.W. Inchbold with those of Turner, it can be seen that the former are distinguished from the latter by a lack of obtrusive facture coupled with a deliberate avoidance of meteorological elements as vehicles of sentiment. This can be read as a deliberate rejection of the visual conventions of the sublime. Central to the Pre-Raphaelite enterprise was its mission of truth to nature, an objective which entailed the accurate study of natural phenomena such as rocks and vegetation. Pre-Raphaelite landscapes are typically small scale, bright, densely articulated and distinguished by abrupt disjunctions of scale and non-linear flattening qualities. In eschewing the Burkean idea of darkness and obscurity in favour of precise delineation, the artists involved in the movement saw nature as something to be inspected and understood, and conveyed in precise analytic terms. The empiricism that underpins the ideology of the Pre-Raphaelite landscape went hand in hand with a suburban outlook, a rejection of the traditional loci of the sublime in favour of mundane places, which, for Ruskin among others, were not worthy of representation.

Despite his keen interest in Pre-Raphaelitism Ruskin could not abide landscapes that showed evidence of human interference, hence his disapproval of Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed and Ford Madox Brown’s An English Autumn Afternoon 1852–5 (Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery).17 In a frequently quoted exchange with Brown, Ruskin asked the painter why he had chosen ‘such a very ugly subject’ for his work, painted from the first-floor back window of the house in which Brown lodged in Hampstead High Street, looking north-east towards the neighbouring suburb of Highgate. The artist’s terse reply, ‘Because it lay out of a back window’, was not just a spontaneous response to the unexpectedness and rudeness of Ruskin’s comment but one which betrays his disavowal of the picturesque and sublime qualities Ruskin found in Turner.18

It was not just the site that offended Ruskin but also Brown’s representation of a couple in the foreground surveying a prospect replete with activity. As the scholar Alistair Wright has argued, it is this very act of looking that ‘desublimates’ the landscape, signalling a departure from accepted ways of viewing painted landscapes which ‘typically demand looking at the landscape with eyes freed from attention to the material realities of the scene, envisioning landscape not as land but as pure visual stimulus, to be cast into an artistic category such as the sublime or the picturesque’.19 The introduction of contemplative watchers was an effective device for showing how aesthetic experience could be focused on the observing subject. The works of the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, for example, frequently include a figure seen from behind gazing upon a view. But whereas the scenes depicted in Friedrich’s landscapes give a strong sense of perceiving something infinite and limitless, the proliferation of information in Brown’s painting invites us to attend to the specifics of the prospect thus undermining the unifying experience of the sublime.

John Constable 1776–1837

Branch Hill Pond, Hampstead Heath, with a Boy Sitting on a Bank circa 1825

Oil on canvas

support: 333 x 502 mm; frame: 579 x 747 x 105 mm

Tate N01813

Bequeathed by Henry Vaughan 1900

Fig.4

John Constable

Branch Hill Pond, Hampstead Heath, with a Boy Sitting on a Bank circa 1825

Tate N01813

Victorian geology and the sublime: William Dyce’s Pegwell Bay

The Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on particularity was paralleled by the great surge of interest in natural history during the mid-nineteenth century, with its panoptic scope and sense of awe generated by the infinitude and intricacy of the natural world. The term ‘science’, which had formerly meant ‘knowledge’ in a general sense, was now taking on a more specialised modern meaning. It had a particular appeal for artists who upheld ‘truth’ as the primary goal of art. As the geologist D.T. Ansted argued in an essay on science and art in Art Journal in 1863:

if truth is once lost sight of, all that is taught leads only to error and confusion and a false appreciation of beauty. There should indeed be no worship of nature, for Art must not be pantheistic; but to ensure due appreciation without misdirected enthusiasm, truth alone is sufficient and necessary.20

Paradoxically, the emphasis on specificity which science bestowed on the humanities offered a new language for evoking the sublime, as science opened up fresh insights on unfathomable concepts such as time, space and existence, which both enthralled and terrified the beholder.

William Dyce 1806–1864

Pegwell Bay, Kent - a Recollection of October 5th 1858 ?1858–60

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 889 mm; frame: 950 x 1200 x 125 mm

Tate N01407

Purchased 1894

Fig.5

William Dyce

Pegwell Bay, Kent - a Recollection of October 5th 1858 ?1858–60

Tate N01407

The final comment is indicative of Dyce’s radical departure from the traditional language of the sublime in attempting a new form of visual expression. In the painting, the beholder’s experience of awe is generated by a sense of vastness signalled by the faint rendition of Donati’s comet in the sky observed only by the artist-spectator holding a telescope on the right of the painting. The comet is so remote in space as to be nearly invisible to the naked eye and is not heeded by the various family members on the beach.22 The myopic gaze of the two centrally placed women is focused on the task of collecting shells or fossils, which signify deep time and, like the comet, render the individual human life insignificant by comparison. By inviting the viewer to identify with the figures looking beyond the frame at the infinite magnitude of nature, Dyce’s painting can be seen to invoke Kant’s notion of the ‘mathematical sublime’ – the idea of the mind using the power of reason to extend beyond its boundaries to think about what the imagination cannot comprehend, in this case, time and space stretching out to infinity.23 As a deeply devout High Anglican, Dyce probably intended these figures (especially the spectator gazing at the comet) to act as guides in eliciting feelings of wonderment in the beholder – an idea that connects with the poet and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s notion of the sublime in which individual consciousness is subsumed by a sense of the eternal.24 On the other hand, the strange bleakness of the scene – the estrangement between figure and setting and the fact that the bending foreground figures do not share this sense of awe – could be interpreted in terms of doubt or a negation of the experience of the sublime in nature.

William Holman Hunt’s Our English Coasts

Holman Hunt took the quest for symbolic representation to greater extremes than Dyce. In so doing, he connected with Coleridge’s theory that the symbol was a form of knowledge that collapsed the distinction between subject and object. It was Hunt who aspired to make representation symbolic of eternal truths in a way that parallels Coleridge’s idea that an object can stand as a metaphor of the ineffable.25 The tension between materialism and symbolism, which could be taken to signal the failure of the visual in evoking the sublime, lies at the heart of Hunt’s project. From the time of his religious conversion when painting The Light of the World in 1851–2 (Keble College, Oxford), the idea of truth to nature became a moral imperative because Hunt believed that nature was the repository of transcendent truth. His reading of Ruskin’s Modern Painters in 1847 had convinced him of the necessity of fusing moral content with realism in his art, and he adopted Ruskin’s use of typological symbolism (reading prophecy backwards) to show it was possible to combine realism with symbolism without distorting the former by falling back on redundant allegorical modes. As the Illustrated London News later stated of Hunt’s work: ‘For Mr Hunt the mission of the painter is to search the world through in the scientific spirit of the geologist or comparative anatomist in order to present a fact of momentous importance with the utmost attainable veracity.’26

William Holman Hunt 1827–1910

Our English Coasts, 1852 ('Strayed Sheep') 1852

Oil on canvas

support: 432 x 584 mm; frame: 785 x 940 x 85 mm

Tate N05665

Presented by the Art Fund 1946

Fig.6

William Holman Hunt

Our English Coasts, 1852 ('Strayed Sheep') 1852

Tate N05665

However, in the painting Hunt uses geological features to explore the spiritual and moral condition of the nation, thus creating a highly ambiguous image. At first sight the painting is a seemingly credible replication of a stretch of vulnerable coastline comprised of clay and sandstone running westwards from Fairlight Glen through Hastings to Bexhill. The landslip in the centre of the image is shown to have been caused by the deposition of what geologists would term ‘competent’ hard solid sandstone on ‘incompetent’ clay or on rock that is soft and easily eroded. The sheep in the foreground stumble across an outcrop of rock, then a famous beauty spot known as the Lovers’ Seat, which was itself swept away by a huge landslip in 1979. By attending, albeit inadvertently, to the past and future degradation of the land, Hunt subtly imposes another layer of meaning in representing a group of unsupervised sheep grazing on insecure rock.

The instability of the rock has been viewed as symbolic of rifts in the established Church, a response to Ruskin’s 1851 pamphlet, Notes on the Construction of Sheepfolds, in the analogy made there between sheep lost in brambles and thickets and the established Church distracted from its mission by sectarian disputes and vulnerable to the threat of Roman Catholicism from across the Channel. Viewed in relation to the date in the title of the painting, the image has also been interpreted as a political satire on the hapless state of the nation’s defences in light of the French invasion scare ignited by the ushering in of the Second French Empire by Napoléon III in December 1852.27 Viewed symbolically, the incompetence of the rock thus provides an apt although arcane metaphor for the artist’s pessimistic view of the nation’s moral substance and spiritual foundations. It is significant that Hunt sets the scene late in the day, as conveyed by the ominous lengthening shadows on the distant hill, which suggests it will not be long before the sheep are plunged into darkness and lose their footing.

Hunt’s quest to charge the material world with sublime meaning was not easily apparent to the eye and required verbal intervention to make clear his underlying symbolic programme, hence the inscription ‘The Lost Sheep’ on the now lost original frame. In 1864 Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote a moral interpretation of Hunt’s painting:

Glimmer’d along the square-cut steep.

They chew’d the cud in hollows deep;

Their cheeks moved and the bones therein.

The lawless honey eaten of old

Has lost its savour and is roll’d

Into the bitterness of sin.

They chew’d the cud in hollows deep;

Their cheeks moved and the bones therein.

The lawless honey eaten of old

Has lost its savour and is roll’d

Into the bitterness of sin.

What would befal the godless flock

Appear’d not for the present, till

A thread of light betray’d the hill

Which with its lined and creased flank

The outgoings of the vale does block.

Death’s bones fell in with sudden clank

As wrecks of minèd embers will.28

Appear’d not for the present, till

A thread of light betray’d the hill

Which with its lined and creased flank

The outgoings of the vale does block.

Death’s bones fell in with sudden clank

As wrecks of minèd embers will.28

In the poem God’s vengeance is heralded by a sudden shaft of light which illuminates the steep stone descent and betrays the deceptive nature of the ground. Ruskin similarly came to perceive Hunt’s painting in biblical terms, identifying it with Isaiah53:6, ‘All we like sheep have gone astray’, and so likewise employed the written word to resublimate a work which ostensibly takes the form of a pastoral picturesque landscape.29 The use of light as a metaphor for God’s judgement and presence is a thread that runs through Hunt’s work and brings to mind Turner’s expression of the sublime as brilliant light in contradistinction to Burke’s preference for darkness as the most fitting agent for revealing sublime power.30 Whether Our English Coasts actually succeeds or not in using material phenomena as ‘proof’ of divine providence, the painting can be seen as an attempt to forge a new scientific language for conveying the apocalyptic sublime in deliberate disavowal of the pictorial conventions of the past.

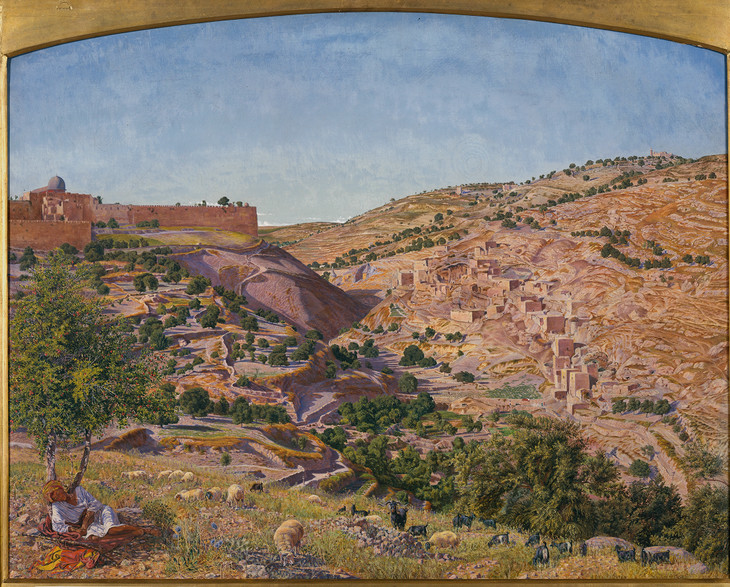

Thomas Seddon’s Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat

Thomas Seddon 1821–1856

Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from the Hill of Evil Counsel 1854–5

Oil paint on canvas

frame: 870 x 1030 x 100 mm; support: 673 x 832 mm

Tate N00563

Presented by subscribers 1857

Fig.7

Thomas Seddon

Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from the Hill of Evil Counsel 1854–5

Tate N00563

This work shares many of the visual characteristics of Our English Coasts: a similar compositional plunge into space and a preoccupation with loose, semi-consolidated rock to convey a sense of instability as well as symbolic meaning. Seddon’s view was from a hill to the south of the Temple Mount that encompassed the Mount of Olives on the right and the Garden of Gethsemane, the scene of Christ’s mental agony before the crucifixion, a choice which may have been informed by the artist’s reading of John Keble’s popular series of poems, The Christian Year (1827). The valley of Jehoshaphat was also believed to be the site of the Last Judgement, hence the foreground motif of the shepherd with his sheep and goats, a reference to Christ’s figurative description of the separation of the blessed and the damned at the end of the world.31 However, Seddon’s tranquil landscape, still in the heat of the afternoon sun, hardly gives any indication of such an apocalyptic event. This may explain why he planned to append his Miltonic poem Moriah to the painting in order to make apparent its underlying symbolic significance. As the scholar George Landow has explained, Moriah, which is another name for the Temple Mount, was a sacred place where God had appeared to men, changing their lives and religion, and where he had brought about the events that prefigured the coming of Christ.32 The fact that Seddon contemplated resorting to verbal exposition to enrich the imaginative and symbolic significance of the scene suggests that the visual language of Pre-Raphaelitism risked being just a dry scientific record of external phenomena and that the sublime significance of the scene was better evoked through verbal means. In the event, the poem was not attached to the work, most likely because Seddon was not able to resolve it into a satisfactory final version before his premature death in 1856.

In a speech he gave at a meeting held in the wake of Seddon’s death, Ruskin applied the term ‘historic landscape art’ to the artist’s works praising them for their accuracy but nothing more. The following year he spoke of two distinct types of Pre-Raphaelitism, the poetic and the prosaic – one concerned with the imagination, the other with science – and contended that the latter was most significant for modern times in recording monuments of the past and scenes of natural beauty threatened by forces of modernisation.33 This view helps explain the influence Ruskin had on protégés such as J.W. Inchbold and John Brett, artists whose devotion to Ruskin’s idea of the ‘prosaic’ presented problems for their expression of the sublime. In a diary entry for April 1852, Brett posed himself the question, ‘which is more noble, Art or Science?’ and went on to suggest that

Art has its foundation in mental philosophy and deals with the influences of the external world upon mind: science deals with the external independently of mind ... science has matter abstractedly and irrespective of its relation to man for its field and its business is to appropriate to mind – a knowledge of that by which it is surrounded ... but Art’s business is to appropriate that knowledge to the soul of man.34

Here Brett presents science and art as two binary models for human knowledge and appears to be sceptical of any synthesis, perhaps because he felt that if art were to capitulate to the demands of science it risked losing its fundamental human perspective.

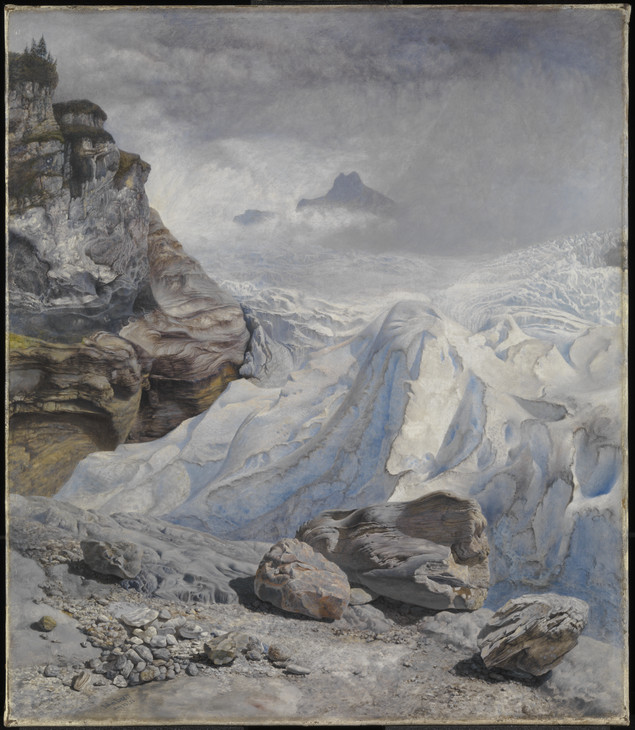

John Brett’s Glacier of Rosenlaui

John Brett 1831–1902

Glacier of Rosenlaui 1856

Oil paint on canvas

support: 445 x 419 mm; frame: 690 x 603 x 71 mm

Tate N05643

Purchased 1946

Fig.8

John Brett

Glacier of Rosenlaui 1856

Tate N05643

Brett’s attention to the actual structural features of the rocks – their folds, lamination and deformation indicating the flow of ice over successive epochs – shows how he was familiar with the main geological and glacial controversies of his day. He would, for example, have been familiar with Louis Agassiz’s influential Études sur les glaciers of 1840 and Charles Lyell’s 1853 edition of the Principles of Geology, both of which explain the mechanics of glaciation, refuting earlier diluvial and catastrophist theories which would have argued that the foreground boulders had been deposited by the biblical flood. As the scholar Marjorie Hope Nicolson has explained, the theological controversies over the earth’s present form which developed from the late seventeenth century onwards had helped to generate an interest in the natural sublime.38 Ruskin’s writings represent an extension of this debate and in the fourth volume of Modern Painters he frequently dwelled on the possibility that the present structures of the earth were the ruins of what was once a greater more perfect beauty:

The present conformation of the earth appears dictated ... by supreme wisdom and kindness. And yet its former state must have been different from what it is now; as its present one from that which it must assume hereafter. Is this, therefore, the earth’s prime into which we are born: or is it, with all its beauty, only the wreck of Paradise?39

The pictorial forms in Glacier of Rosenlaui appear to writhe with movement as if still in the process of formation. Brett’s preoccupation with detail could thus be seen as a form of ‘inscape’ (to adopt Gerard Manley Hopkins’s term), underscoring a naturalist religion that extols the enduring power of God in shaping nature. However, the lack of any sign of human life, coupled with the frozen static quality of the image, functions to bring these examples of ancient time into an uneasy conjunction with the present (suggested by the more recent timescale of the glacier and temporal meteorological conditions). Here the rocks seem to represent a time so ancient that they render useless any attempt to impose human meaning or to suggest a directional purpose behind creation. Ruskin was later to argue that the sublime required an imagined human presence as an emotional centre, so a spectator or other human being should be placed within the scene. Lacking a human presence, Brett’s Glacier of Rosenlaui occludes any sense of scale, particularly in the transitional area between the foreground ledge and the cusp of the glacier, making it difficult to ascertain the actual scale of the boulders. While these could be regarded as protecting the viewer from a sense of vertigo or from looking down into the abyss below the glacier, they also hover precariously on the edge, vicariously threatening the stability of the spectator’s vantage point.40 The effect is to alienate the viewer from the composition, negating the experience of the sublime in the Ruskinian sense of enhancing the beholder’s sense of moral worth, positing instead the question of nature’s indifference to humanity.41

The resublimation of nature

The difficulties audiences experienced in extracting ideas from works like Our English Coasts and Glacier of Rosenlaui were probably caused by the wealth of visual information provided by the artists which frustrated the detection of any deeper meaning. Literary metaphor, by contrast, did not hinder the expression of metaphysical insight in the same way. With the passing of Pre-Raphaelitism in the 1860s there developed the idea that the aims of art should diverge from those of science and that the former should be competent on its own terms. The preoccupation with the aforementioned notion of ‘affect’ in later Victorian landscape painting is most apparent in those works which manipulate the medium to convey an experience of immersion in nature by emphasising atmospheric and meteorological elements. In his essay ‘Modern English Landscape Painting’ of 1880, the landscape painter Alfred William Hunt argued that the quest for truth which underpinned Pre-Raphaelitism had led to an awareness that this quality was ultimately impossible to achieve in representation:

Our hearts are not touched: we admire the artist’s extraordinary skill, we are thoroughly grateful to him for reminding us of what he has copied so well; but the admiration and the gratitude and the intellectual joy of examining bit by bit such a picture, make up altogether a pleasure different in kind from that which we derive from a great imaginative work of art.42

Turner was for Hunt the greatest imaginative painter and he was not alone in engaging with his art at this time. Thus, in many respects landscape painting from the late 1860s can be seen as a retreat back to Romantic notions of the natural sublime, particularly in terms of scale, facture and choice of location.

The return to the sublime aesthetic can also be seen as a response to what has broadly been described as a crisis of faith following the spread of Darwinian theories of natural selection and evolution, together with a growing concern about the consequences of industrialisation and urbanisation on the environment. In keeping with Burke’s mission to find a secular language for profound human experience, the renewed interest in the sublime could be seen as an attempt to find a new non-religious language for spiritual belief. On the other hand, for those who retained a sense of faith the sublime represented a form of religious experience. Either way, landscape became at this time a metaphysical realm for the projection of emotion – a sort of liminal space that traversed fact and feeling and in which nature functioned as a reflex of the viewing subject.

Landscapes of immersion: John Brett’s The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs and John Everett Millais’s Dew-Drenched Furze

John Brett 1831–1902

The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871

Oil on canvas

support: 1060 x 2127 mm; frame: 1390 x 2458 x 121 mm

Tate N01902

Presented by Mrs Brett 1902

Fig.9

John Brett

The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871

Tate N01902

More significantly, perhaps, the intense blue admits a transcendental dimension lacking in the Rosenlaui picture. The rays which spotlight the centre and push back the horizon propose the idea of the sea as a space for contemplating the variants of existence, as in the poetry of Alfred Tennyson, Matthew Arnold and Algernon Charles Swinburne, all of whom wrote in symbolic terms about the sea and seashore. Brett was one of the few Pre-Raphaelite landscape artists who lost his faith; certainly, by the time he completed this work he was an affirmed atheist. However, in confronting a void saturated with glowing light and colour, his image evokes the sublime effects created in Baroque trompe l’oeil painting, as if he intuitively sought to recast traditional religious modes of the sublime into a modern secular language. This approach could be described as a post-religious condition of emotional transcendence, aimed at eliciting a sense of exaltation and release rather than fear or anxiety.

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt 1829–1896

Dew-Drenched Furze 1889–90

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1732 x 1230 x 27 mm

Tate T12865

Presented by Geoffroy Millais in memory of his late father, Sir Ralph Millais Bt 2009

Fig.10

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt

Dew-Drenched Furze 1889–90

Tate T12865

Calm and deep peace on this high wold,

And on these dews that drench the furze,

And all the silvery gossamers

That twinkle into green and gold.45

And on these dews that drench the furze,

And all the silvery gossamers

That twinkle into green and gold.45

Seen in relation to the verse, the filigree patterns of dew-drops across the surface quicken the viewer’s apprehension of perceiving something extraordinary in what could otherwise be taken as a nondescript patch of nature. Moreover, the imagery of both painting and poem can be seen to echo Tennyson’s metaphor of a veil hiding the divine mystery of nature, expressed elsewhere in the poem, ‘thy voice to soothe and bless ... Behind the veil, behind the veil’, thereby admitting a sense of the numinous or of nature as sacred mystery.46 The lack of human presence within the picture paradoxically heightens the role of the spectator in beholding the scene. The central vista framed by large trees on the edges allows the eye to wander across the enticing, but in reality threatening, mass of sharp gorse towards the light penetrating the wood in the distance. Millais’s abstract evocation of the suffusing energy of the sun, made all the more poignant through the reference to In Memoriam, has the effect of increasing the spectator’s sense of being, or what Ruskin would term moral worth, one of his key tenets of the sublime.

William Holman Hunt’s The Triumph of the Innocents

While it is possible to contend that the resublimation of nature seen in the landscapes of Brett and Millais was aimed at conveying experiences of self-transcendence that lifted the beholder beyond forms of understanding invited by earlier Pre-Raphaelite conventions, the rhetoric of the apocalyptic sublime could still appeal to those for whom the language of the biblical sublime continued to carry meaning. Holman Hunt was one such artist who, in the work he produced in Palestine, strove to place natural phenomena in a wider eschatological framework. It was during the time he spent in the Holy Land that he assumed the mantle of a prophet, discovering in the stony arid landscape messages pertaining to the promise of millennial judgement and revelation. For Hunt, scientific study was the gateway to religious insight and he was critical of Ernest Renan’s Vie de Jésus (The Life of Jesus, 1863) – a biography of the historical figure of Jesus that rejected the belief that he was the son of God and could perform miracles – for its ‘lack of imagination concerning the profundity and sublimity of the mind and purpose of Jesus’.47 While Hunt aspired to join the real and the visionary in his work, he explicitly rejected Baroque conventions of fusing the natural and supernatural through effects such as billowing clouds and radiant shafts of light. However, he was interested in employing light and dark to establish the actual and metaphysical significance of a religious scene. He manipulated these qualities to communicate the polarities of religious epiphany and doubt, and delved further in exploring the properties of supernatural or what he termed ‘psychedelic’ colour to express spiritualism and the otherworldly.

William Holman Hunt 1827–1910

The Triumph of the Innocents 1883–4

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1562 x 2540 mm; frame: 2208 x 3175 x 125 mm

Tate N03334

Presented by Sir John Middlemore Bt 1918

Fig.11

William Holman Hunt

The Triumph of the Innocents 1883–4

Tate N03334

The visionary realism of the picture (the appearance of transcendent beings in a temporal setting) can be described as ‘numinous’ in more overtly spiritual terms than Millais’s Dew-Drenched Furze, discussed above. This word was first coined by Rudolf Otto in The Idea of the Holy (1917), a text that posited the numinous as an idea of mystery and otherness that connected with the sublime. Although Otto was careful to distinguish the numinous from the sublime, defining the former as a type of religious experience, he nevertheless felt they were connected in that neither could be explicated and both were mysterious and intensely compelling for the beholder.50

The viewer is invited to partake of the numinous by sharing the Christ child’s encounter with the supernatural spectacle of the resurrected infants, Christ being a figure who traverses the boundaries of time and eternity. On the other hand, the spectator is also given reason to doubt their real presence by identifying with Mary, dimly prescient of their existence, and Joseph, who is altogether unaware of them, absorbed as he is in the task of ensuring his family’s safety. The effect of awe generated by the image thus relates to the audience’s inability to decide in which realm the event takes place – the real or imagined – resulting in a strangeness of vision that accords with Ruskin’s notion of the grotesque as a concept that offered a partial glimpse of the sublime. For Ruskin, the grotesque involved the play of the imagination to produce a perception of the sublime in the beholder. He therefore divorced the grotesque from its connection with the satanic and immoral to show that it was capable of enhancing the imaginative and moral faculties of the beholder:

The grotesque which comes to all men in a disturbed dream is the intelligible example of this kind but also the most ignoble; The imagination, in this instance, being entirely deprived of all aid from reason, and incapable of self-government. I believe, however, that the noblest forms of imaginative power are also in some sort ungovernable, and have in them something of the character of dreams; so that the vision, of whatever kind, comes uncalled, and will not submit itself to the seer, but conquers him, and forces him to speak as a prophet, having no power over his words or thoughts.51

For Ruskin, The Triumph of the Innocents was the most important work of Hunt’s career and ‘the greatest religious painting of our time’, maybe because it exemplified the grotesque as expressed in the above passage.52 Relevant to this interpretation are the problems Hunt encountered when working on the first version. He had to contend not only with the threat of typhoid fever but also with the anxiety caused by the dangerous political situation in Jerusalem following Russia’s declaration of war against Turkey in 1877, which led him to evacuate his family to Jaffa to escape what he feared would be a massacre of Christians in the area. Back in London he experienced technical problems and having had the linen support backed with canvas he found the centre of the picture beginning to twist. This made him suspect that demonic interference was preventing the work’s completion, causing him to temporarily abandon the painting and commence the second Tate version. Hunt’s problems culminated in an extraordinary psychic encounter with the devil when working on the painting at his studio in London on Christmas day 1879, as he explained in a letter to his friend William Bell Scott:

I hung back to look at my picture. I felt assured that I should succeed. I said to myself half aloud, ‘I think I have beaten the devil!’ and stepped down, when the whole building shook with a convulsion, seemingly immediately behind the easel, as if a great creature were shaking itself and running between me and the door ... I noticed that there was no sign of human or other creature about. I went back to my own work really rather cheered by the grotesque suggestion that came into my mind that the commotion was the evil one departing.53

The Triumph of the Innocents took on a sublime dimension for Hunt, introducing him to experiences of transcendence, terror and the uncanny. How far this experience transfers to the viewer depends on our ability to engage with the work on an aesthetic and psychological level, a challenge for audiences living in a secularised and religiously sceptical culture.

George Frederic Watts and the abstract sublime

Ruskin also championed the art of George Frederic Watts in his later years, claiming that Watts, like Hunt, maintained an ethical role for art in using the visual to express the fear and mystery of the unknown. Of all the painters discussed in this essay, the art of Watts comes closest to the Romantic sublime of Turner as his works encompass subjects relating to the apocalyptic, biblical and Miltonic sublime. In contrast to Hunt’s religious art, which was grounded in typological exegesis, Watts saw himself as a deist, one who felt the immanence of a higher presence without subscribing to any particular doctrine.

Watts was interested in expressing absolutes and a key strand in his thinking was that life was conducted through impersonal motive forces, a notion he probably adapted from Darwin via the writings of the widely read thinker and journalist Herbert Spencer. It was Spencer who coined the term ‘survival of the fittest’, famously adopted by Darwin in the later editions of Origin of Species to define the operation of natural selection. Watts also appropriated this phase, on one occasion defining this struggle as a ‘law of combat’ through which individuals, groups and nations fight to realise individual identity.54 Watts comes close to Spencer and Darwin in imagining the universe held together by a compound of conflicting forces, and in maintaining that it was only through a process of struggle that it could evolve into a higher synthesis of matter and spirit. Given his belief in vitalism – that there is a mysterious vital force in organisms that cannot be explained by science – it is hardly surprising that Watts was wary of giving precise form to that which he felt could not be fully defined, instead developing a visual language that comprised webs of dense colour to simultaneously monumentalise and dissolve form. Likewise, in his written thoughts Watts avoided the particular in favour of grand statements about existence and creation as if he were attempting to harmonise the visual and verbal in evoking the sublime:

In the grandeur and universality of astronomical phenomena we forget the insignificant. Life in all its forms, in all its restlessness, in all its pageantry, disappears in the magnitude and remoteness of the perspective. The mind sees only the gorgeous fabric of the universe, recognises only the divine architect, and ponders but on cycles of glory or of desolation. If the pride of man is ever to be mocked, or his vanity mortified, or his selfishness rebuked, it is under the influence of these sublime studies.55

George Frederic Watts 1817–1904

Chaos c.1875–82

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1067 x 3048 mm; frame: 1395 x 3375 x 90 mm

Tate N01647

Presented by George Frederic Watts 1897

Fig.12

George Frederic Watts

Chaos c.1875–82

Tate N01647

The principles of vitalism and evolution that Watts conveys in Chaos – expressing surges of volcanic energy giving way to consolidated matter using heavy gestural brushwork – finds a parallel in his written ideas on the progress of civilisation. He set these down in his numerous statements on art, particularly in his essay ‘Our Race as Pioneers’:

Civilisation is like a flood, a mighty over-whelming flood, not so much caused by storms, or even the onwards rolling of the great ocean, but by the welling up of the mighty mass of waters from beneath, forcing its way over the earth, steadily and perceptibly rising; and unless outlets be found and channels created (whereby it may be made beneficial and irrigatory), it will submerge much that is fair and worthy of permanence.57

The ambitious reach of Watts’s vision in both his visual and verbal works invites comparison with the writings of another absolutist of the age, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, especially the idea of a ‘dynamic primal unity’ beyond all phenomena which it was art’s purpose to disclose through symbolic form, set out in Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy (1872, revised 1886).58 Like the philosopher, Watts believed that art had a sublime purpose as it aimed at transforming consciousness in the viewer, encouraging an awareness of existence that transcended individuation. From a Nietzschean and Wattsian perspective, wars and natural disasters were sublime rather than merely horrible as through the symbolic medium of art they bestowed grandeur on existence and gave it meaning.

Watts also comes close to Ruskin’s concept of the grotesque in seeking a prophetic role for the artist and in employing paint as a ‘veil’ to offer a partial glimpse of the unknown. Moreover, by using abstract elements to communicate spiritual aspirations Watts can further be seen as an artist who used symbolism to understand areas of human existence that reside beyond the logic of science. In this sense his work connects with the art of other symbolists such as Edward Burne-Jones, as well as painters interested in fathoming the darker, irrational side of the human psyche, such as Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau. Watts’s abstraction can further be seen as a launching pad for sublime abstraction in the twentieth century. The dense patterns of centrifugal energy that characterise Chaos not only echo the Turnerian sublime but pave the way for the apocalyptic proto-abstract landscapes of Wassily Kandinsky. Many of the themes provoked by the post-Darwinian sublime, especially the idea that the modern is as much about the unleashing of unknown terrifying forces as it is about the mastery of the environment, help explain why the sublime continued to be compelling in the twentieth century and remains relevant today.

Notes

See Elizabeth Prettejohn, Beauty and Art: 1750–2000, Oxford 2005 and Art for Art’s Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting, New Haven and London 2007.

Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, ed. by A. Phillips, Oxford 1990, pp.36–7.

See The Oxford Companion to J.M.W. Turner, ed. by Evelyn Joll, Martin Butlin and Luke Herrmann, Oxford 2001, pp.26, 259.

John Ruskin, ‘Modern Painters’, in E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), The Works of John Ruskin, London and New York 1903–12, vol.3, p.572.

George P. Landow, The Aesthetic and Critical Theories of John Ruskin, Princeton, New Jersey 1971, pp.203–4.

John Ruskin, letter to Susan Beever, 21 January 1875, quoted in Leslie Parris, Landscape in Britain, c.1750–1850, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1973, p.133.

For a detailed examination of the relationship between the sublime and the grotesque in Ruskin’s work, see Elizabeth K. Helsinger, Ruskin and the Art of the Beholder, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1982, pp.111–38. A key source for the identification of the grotesque with spiritual insight was Victor Hugo’s Preface to Cromwell of 1827.

William Holman Hunt, letter to John Lucas Tupper, 11 March 1879, in James H. Coombs, Anne S. Scott, George P. Landow and Arnold A. Saunders (eds.), A Pre-Raphaelite Friendship: The Correspondence of William Holman Hunt and John Lucas Tupper, Ann Arbor, Michigan 1986, p.236. Shelley was awarded two stars by the original Brotherhood in their ‘List of Immortals’; see William Holman Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, London 1913, vol.2, p.111.

William Holman Hunt, letter to John Lucas Tupper, 21 April 1897, in Coombs, Scott, Landow and Saunders 1986, pp.275–6.

See http://www.preraphaelites.org/the-collection/1916p25/an-english-autumn-afternoon-1852-1853/ , accessed 13 September 2012.

Ford Madox Brown, diary entry, 13 July 1855, in Virginia Surtees (ed.), The Diary of Ford Madox Brown, New Haven and London 1981, p.144.

Alastair Ian Wright, ‘Suburban Prospects: Vision and Possession in Ford Madox Brown’s An English Autumn Afternoon’, in Margaretta Frederick Watson (ed.), Collecting the Pre-Raphaelites: The Anglo-American Enchantment, Aldershot 1997, pp.192–3.

Professor Ansted, ‘Science and Art V: On the General Relation of Physical Geography and Geology to the Progress of Landscape Art in Various Countries’, Art Journal, December 1863, p.235.

Donati’s comet was seen in Britain in the autumn of 1858, the last time it would be seen for another 21,000 years according to the Illustrated London News. See Marcia Pointon, ‘The Representation of Time in Painting: A Study of William Dyce’s Pegwell Bay: A Recollection of October 5th 1858’, Art History, March 1978, pp.99–103.

Samuel H. Monk, The Sublime: A Study of Critical Theories in Eighteenth-Century England, New York 1960, pp.6–9.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Coleridge’s Writings, ed. by David Vallins, Houndmills, Basingstoke 2003, vol.5, p.87.

Ruskin in Cook and Wedderburn 1903–12, vol.7, p.534; Jonathan P. Ribner, ‘Our English Coasts, 1852: William Holman Hunt and Invasion Fear at Midcentury’, Art Journal, vol.55, no.2, Summer 1996, pp.45–54.

This untitled poem was written when Hopkins was intensely interested in the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic. See R.K.R. Thornton (ed.), All My Eyes See: The Visual World of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Newcastle 1975, pp.92–3.

Matthew 25:31–2; see Nicholas Tromans (ed.), The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painters, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008, pp.166–7.

George P. Landow, ‘Thomas Seddon’s Moriah’, The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Studies, vol.1, 1987, pp.59–65, http://victorianweb.org/painting/seddon/moriah.html , accessed 20 June 2011.

John Brett, diary entry, 23 April 1852, in Charles Brett (ed.), John Brett, Diary 1851–1860, unpublished manuscript, 2002, p.12.

See, for example, Ruskin’s Turnerian watercolour, The Glacier des Bois c.1843–4 (Ruskin Art Foundation), reproduced in Cook and Wedderburn 1903–12, vol.2, opposite p.225.

Marjorie Hope Nicolson, Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetic of the Infinite, Washington 1959. For a full discussion about Diluvial theory, see Rebecca Bedell, ‘The History of the Earth: Darwin’s Geology and Landscape Art’, in Diana Donald and Jane Munro (eds.), Endless Forms: Charles Darwin, Natural Science and the Visual Arts, New Haven and London 2009, pp.52–7.

See Christiana Payne, John Brett: Pre-Raphaelite Landscape Painter, New Haven and London 2010, p.32.

Landow 1971, pp.208–9. Ruskin’s negative praise of Brett’s Val d’Aosta 1858 (Andrew Lloyd Webber Collection) – ‘I never saw the mirror so held up to Nature; but it is Mirror’s work not Man’s’ – further suggests that this type of landscape does not allow for overwhelming aesthetic experience. Ruskin in Cook and Wedderburn 1903–12, vol.14, p.234.

Alfred William Hunt, ‘Modern English Landscape Painting’, Nineteenth Century, vol.7, May 1880, p.785.

Alfred Tennyson, In Memoriam A.H.H., London 1850, canto XI, http://www.archive.org/stream/inmemoriam00tennrich#page/16/mode/2up , accessed 23 June 2011.

Ibid., canto LV, http://www.archive.org/stream/inmemoriam00tennrich#page/80/mode/2up , accessed 23 June 2011.

Dates for the Walker version are: 1876–8, 1879–83, 1885, 1887, retouched 1890; those for the Tate replica are: 1883–5, retouched 1887, 1889, 1890, 1897. There also exists the first and smaller version in the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, painted 1870, 1876, 1884, 1903. See Judith Bronkhurst, William Holman Hunt: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2006, vol.1, pp.238–41, 256–8, 223–4.

First published in Germany in 1917 as Das Heilige – Über das Irrationale in der Idee des Göttlichen und sein verhältnis zum Rationalen (The Holy – On the Irrational in the Idea of the Divine and its Relation to the Rational). English translation 1923.

See George P. Landow, ‘The Triumph of the Innocents’, Replete with Meaning: William Holman Hunt and Typological Symbolism, New Haven and London 1979, http://www.victorianweb.org/painting/whh/replete/triumph.html , accessed 20 August 2009; Ruskin in Cook and Wedderburn 1903–12, vol.11, p.178. For a searching discussion of the Ruskinian grotesque, see Lucy Hartley, ‘“Griffinism, grace and all”: The Riddle of the Grotesque in John Ruskin’s Modern Painters’, in Colin Trodd, Paul Barlow and David Amigoni (eds.), Victorian Culture and the Idea of the Grotesque, Aldershot 1999, pp.81–94.

William Holman Hunt, letter to William Bell Scott, 5 January 1880, in William Bell Scott, Autobiographical Notes, and Notices of his Artistic and Poetic Circle of Friends, 1830–1882, ed. by William Minto, London 1892, vol.2, pp.230–1. In a letter to Hunt about the painting of February 1880 Ruskin wrote, ‘I hope the Adversity may be looked on as really Diabolic and finally conquerable utterly’, as if acknowledging the substance of the artist’s vision. Quoted in Robert Hewison, Ian Warrell and Stephen Wildman, Ruskin, Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2000, p.275.

George Frederic Watts, ‘Thoughts on Life’, in Mary S. Watts, George Frederic Watts, London 1912, vol.3, pp.295–6.

Watts’s 1884 description of Chaos is reproduced in Emilie Isabel Barrington, G.F. Watts: Reminiscences, London 1905, pp.131–3.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the two anonymous readers of the first draft of this essay for their comments.

I am grateful to the two anonymous readers of the first draft of this essay for their comments.

Alison Smith is Curator (Head of British Art to 1900), Tate Britain.

How to cite

Alison Smith, ‘The Sublime in Crisis: Landscape Painting after Turner’, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013, https://www