Longinus and the Baroque Sublime in Britain

Lydia Hamlett

The impact of the sublime in seventeenth-century visual culture has often been overlooked, overshadowed by the late eighteenth-century Romantic sublime. Lydia Hamlett here traces an earlier sublime in the British Baroque period, drawing on the writings of the classical author, the Pseudo-Longinus.

Some twenty years before the milestone publication of Edmund Burke’s famous 1757 text on the sublime, the painter and theorist Jonathan Richardson encapsulated in his writings the multifaceted definitions of the visual sublime and the struggles to define it.1 The examples of the sublime in art that Richardson offers range in authorship, geography, chronology, genre and medium. But, he stressed, all are useful to the critic for the strong interaction of their styles with the spectator. In the first edition of An Essay on the Theory of Painting published in 1715, Richardson proposed the art of Michelangelo as an exemplar of the sublime. In the second edition of 1725 Raphael eclipsed Michelangelo. The author also gave further examples of the sublime: a sketch of a dying man by Rembrandt and an Annunciation by Federico Zuccaro. In the interim, in Two Discourses (1719), Richardson judged a portrait by Van Dyck of the Countess Dowager of Exeter to be sublime.

This essay asks why a British theorist, who was well acquainted with the classical rhetorical treatise Peri Hypsous (‘On Height’, later translated as ‘On the Sublime’) by the author known as the Pseudo-Longinus,2 considered it appropriate to apply its rules directly to such diverse works of art, and considers what such judgements can tell us about the effects and affects of British art of the period.3 Samuel H. Monk’s seminal study on the sublime in England, first published in 1935, examines the development from what the author describes as a neoclassical to a Romantic sublime, occurring largely over the course of the eighteenth century. In doing so, Monk plays down the influence of Pseudo-Longinus’s Peri Hypsous before this time.4

In this essay I re-examine the impact of Pseudo-Longinus’s treatise, looking at discussions of visual culture in Europe over the two centuries from the rediscovery of Pseudo-Longinus in 1554 to the publication of Burke’s 1757 text, after which the sublime was supposedly defined aesthetically and became the context in which much British art of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was discussed. More specifically, I show how a reconsideration of the notion and limits of the sublime can inform our understanding of how British art and architecture of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries was informed by a wider European ‘Baroque’ aesthetic, shaped largely by the Catholic Counter Reformation.5 The context of the ‘Burkean sublime’ has mainly been interpreted alongside neoclassical art, but the meaning of the term ‘sublime’ in the context of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Britain has largely been ignored. It is proposed here that the neoclassical sublime was a reaction to an earlier Baroque sublime.

Pseudo-Longinus, Peri Hypsous and visual imagery

Pseudo-Longinus’s Peri Hypsous was first published in 1554 in Basel, Switzerland, shortly followed by another edition in Venice. Over the next two hundred years around thirty further editions appeared in various languages across Europe.6 Intended essentially as a handbook on the rousing power of rhetoric, the treatise’s popularity demonstrates its sustained influence on early modern western culture. Its precise impact on the visual arts, or even on rhetoric, in Britain is not easily determined.7 Yet this period of interest in Peri Hypsous coincided with a time when effect and affect, as well as an intense identification with the spectator, were considered to be especially important and when both Church and state were attracted to powerful persuasive rhetorical systems. The emphasis of a ‘Longinian sublime’ on composition and effect, in order to excite, elevate and persuade an audience, has strong trans-disciplinary ramifications.8

In Peri Hypsous Pseudo-Longinus described what he felt to be the best way of conveying a message to create the most heightened effect in the receiver (the audience or reader). He argued that the orator should maintain such a connection with the audience as to make them think that they had thought of the speaker’s idea themselves, or, in terms of classical rhetoric, could see what the orator described within their mind’s eye.9 The aim, reiterated throughout, was not merely to persuade but to move the receiver, to raise passions and to inspire.10 The attempt to identify with one’s audience and to maximise the potential for effect (and, indeed, affect) was to be achieved through various means, including composition, subject matter and capturing the imagination. To reach the highest form of rhetoric was Pseudo-Longinus’s goal but, paradoxically, perfection was far from vital and frequently rejected in the pursuit. He made no specific link between the sublime and terror (although terrible ideas could be sublime) and, similarly, no contrast was made between the sublime and the beautiful.11 If there happened to be a single quality that led to the sublime, it was not its form per se, but rather its impact on the receiver. As the critic and poet Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux wrote: ‘The sublime is not strictly speaking something which is proven or demonstrated, but a marvel, which seizes one, strikes one, and makes one feel.’12 Far from perfect proportion being a prerequisite or even an ambition of the sublime, the sublime was to be found rather in the effects of such perfect harmony, and in this it reached beyond formal boundaries.

It is Pseudo-Longinus’s few references to natural objects that connect him with later discourses on the sublime, despite the fact that most are intended as metaphors for the power of language or even for other writers.13 However, Pseudo-Longinus also uses natural phenomena to demonstrate the effect of physical size, claiming that ‘whatever exceeds the common Size is always great, and always amazing’.14 He goes on to compare favourably the effects of viewing great natural objects, including oceans and volcanoes, with their less impressive domestic counterparts, rivulets and hearth fires. These passages became increasingly relevant over the course of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as foreign travel increased and the sublime became more frequently linked with the mixture of awe and terror described by the critic John Dennis and others and which was distilled aesthetically in Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry.15

As well as natural matter, Pseudo-Longinus occasionally uses man-made objects as visual metaphors too. In his discussion of choosing words, he likens a wise selection to an artistic composition: ‘This cloaths a Composition in the most beautiful Dress, makes it shine, like a Picture, in all the Gaiety of Colour; and in a Word, it animates our Thoughts, and inspires them with a kind of vocal life ... Fine words are indeed the peculiar Light in which our Thoughts must shine.’ Meanwhile, the effect of ill-fitting terms is likened to the awkwardness of a tragic mask on the face of an infant.16 Sometimes he gives us an idea of what he considered to be a visual sublime, namely greatness of size and abundance of variety. The first quality is illustrated by his admiration for the statue known as the Colossus, which he uses as an example to show that correct proportions are not necessarily part of the sublime effect.17 In another example he contrasts the opposing descriptions of items taken by Theopompus’s warriors on the Persian expedition, bemoaning the listing of mundane objects next to the ‘massy Goblets adorned with inestimable Stones, or of Silver embossed, and Tents of golden Stuffs’.18 The implication is that the sight of the everyday items tarnishes the sublime vision of the noble entourage, itself conjured by the expensively decorated objects.

But what Peri Hypsous is primarily concerned with is not the visual effect of natural or man-made objects but the skilful art of language, composition and its effects, and it is this that we can most usefully parallel with the aims of art in the late sixteenth to early eighteenth centuries. Pseudo-Longinus refers both to the visual arts and music in the course of his discussions on composition, emphasising that the sublime is something that can be manipulated for effect but that the passion must be real for the effect on the audience to be genuine.19 Anyone can be taught to create the sublime and it is also potentially universally affecting: ‘In a word, you may pronounce that sublime, beautiful and genuine, which always please and takes equally with all sorts of Men.’20 For Pseudo-Longinus, the relationship between performer and audience is paramount in the creation of the sublime.21 Moreover, the manuscript was brought to light at the very time that rhetoric became implicit in the aims of artworks and when persuasion and movement appear to have evolved as key elements of the so-called ‘Baroque’ visual style.22

In relation to the visual arts what is also important in Peri Hypsous is the interest in earthly wonders as a vehicle to the divine and the freedom and transport offered by the journey to the celestial sphere. At the start of his text Pseudo-Longinus explicitly states that his aim is to offer advice to those who speak in the earthly sphere but who must constantly ask themselves, as translated by William Smith in 1739, ‘In what do we most resemble the gods?’.23 John Hall muses in the ‘Dedication’ to his much earlier translation of Pseudo-Longinus, the first to be published in English, in 1652, that ‘there must be somewhat Ethereall, somewhat above man, much of a sort separate, that must animate all this, and breath into it a fire to make it both warm and shine’.24 There are recurring references to the space between heaven and earth, people ascending as close as possible to the gods and traversing the space between earth and heaven.25 Perhaps it is for this reason that the Latin translation of Peri Hypsous (On Height) was De Sublimitate (On the Sublime), which comes from sub limen, meaning literally ‘under’ or ‘up to’ the ‘lintel’, implying the upper limits of the earthly sphere touching the rim of heaven, the sky, the cielo, vault or ceiling. Nature, Pseudo-Longinus says,

never designed Man to be a grov’ling and ungenerous Animal, but brought him into Life, and placed him in the World, as in a crouded Theatre, not to be an idle Spectator, but spurr’d-on by an eager Thirst of excelling ardently to contend in the Pursuit of Glory. For this purpose she implanted in his Soul an invincible Love of Grandeur, and a constant Emulation of whatever seems to approach nearer to Divinity than himself. Hence it is, that the whole Universe is not sufficient for the extensive Reach and piercing Speculation of the human Understanding. It passes the bounds of the material World, and launches forth at pleasure into endless Space.26

The ‘raising’ of the spectator as described in this passage should be central to our understanding of the Longinian sublime and its connection to Baroque art.

William Sanderson’s Graphice and English art theory

The impact of Pseudo-Longinus on English, and indeed European art and theory has not yet been fully investigated, and it is pertinent to point out that Peri Hypsous almost certainly had more of an impact on seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century art and art theory than previously thought. Although this essay is concerned primarily with the theories of Jonathan Richardson, who certainly used and quoted from Pseudo-Longinus, it is useful to read his work in the context of a tradition of Longinian influence.

A few years after Pseudo-Longinus’s treatise on rhetoric was first translated into English by John Hall in 1652, the historian Sir William Sanderson published his own treatise on the visual arts, the flavour of which is summed up by Edmond Gayton’s eulogy to the author at the beginning: ‘What Colours in our Rhetorick, can show Thine, which more various are, than those i’th’ Bow?’.27 The first half of the work intends to persuade us of the potential power of art and the second part divulges the practicalities of how to achieve it. Essentially, Sanderson aims to do for the visual arts what Pseudo-Longinus had done for rhetoric, and in doing so he mirrors many of the terms used by Hall in his translation of Pseudo-Longinus. As Sanderson writes: ‘For Poesie is a speaking Picture, and Picture is a silent Poesie ... In both, an astonishment of wonder; by Painting to stare upon imitation of Nature, leading and guiding our Passions, by that beguiling power, which we see exprest; and to ravish the mind most, when they are drunke in by the eyes.’28 Sanderson’s use of words, such as ‘raising’, ‘ravishing’, ‘astonishing’ and ‘beguiling’, echo Hall’s translation but here they are instead used to describe the powerful effects of sight, rather than of sound or language.29

As if to offer a direct response to Hall’s translation, Sanderson imitates specific sections from Pseudo-Longinus, listing five ingredients to achieve greatness in art, just as the ancient writer had done for attaining rhetorical sublimity. In Hall’s translation Pseudo-Longinus compares the five ‘rich fountains of Sublime Eloquence’ to the foundation pillars of a building, includes: vastness of thought; fierce and transporting passion; a ‘right fashioning’ and variation of figures; generous and select phrase; and nobility and beauty of disposition.30 In comparison, Sanderson offers ‘Invention, Proportion, Colour, Motion, Disposition’ as the five paths to achieving artistic sublimity.31 There are also thematic borrowings from Pseudo-Longinus in Sanderson’s text, including an examination of the words from Genesis ‘Fiat Lux’ (Let there be light), which the latter turns to his advantage by concentrating not on the majestic simplicity of the words but to the primary importance of light, thus supporting the view reiterated throughout that sight is first among the senses.32

Sanderson, like Pseudo-Longinus, is keen to point out that his audience should be universal: ‘all sorts of people, wise and weak, ignorant and Learned, Men and Women, one and all, may find in it, to be delighted, which comes now to be a Wonder.’33 But both his text and Hall’s translation were published during the Commonwealth (1649–1660) when England was a republic marked with powerful and conflicting religious and political tensions. Hall prefaces his translation with a call for the Commonwealth government to use rhetoric effectively with their audiences; likewise the royalist Sanderson emphasised the persuasive effects of art – from easel painting to large scale interiors – on the spectator.34

Italian Baroque art and its British translation

After Federico Zuccaro

The Annunciation with Prophets and music-making angels 1572

Engraving on paper

466 x 679 mm

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.1

After Federico Zuccaro

The Annunciation with Prophets and music-making angels 1572

© The Trustees of the British Museum

It is the aspects of Zuccaro’s Annunciation that Richardson identifies as ‘sublime’ that are revealing. Having labelled unremarkable the depiction of the two central protagonists, the Virgin and the angel Gabriel, Richardson instead marvels at the vastness of the heavens and the innumerable rejoicing angels that convey the subject.39 He is struck by the awe-inspiring effects of the whole, with its hints at eternity and infinitude, and it is this that causes him to pronounce the picture ‘sublime’. More recently, the scholar Michael Bury has described how ‘The heavenly vision above, through the brilliant handling of light and shade, gives the most spectacular effect of infinite space’.40 While Richardson did not see the work in the magnificent architecture for which it was intended, it was common to describe a painting’s effects from its engraving and he is also perfectly within the bounds of the seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century practice of describing both real and imagined artistic interiors:

He has made an Annunciation, so as to give such an Idea as we ought to have of that Amazing Event, The Angel, and Virgin have nothing particularly remarkable but Above is God the Father, and the Holy Dove with a Vast Heaven where are Innumerable Angels Adoring, Rejoycing.41

He is surely using his imagination in this passage, projecting the engraving into its original, elevated context in the apse over the main altar of the church. On this occasion it was in an ecclesiastical setting but it was a genre that was equally popular in secular and domestic spaces across Italy and was later adapted to English court and country house interiors.42

Decorative history painting, effect, and affect

Baroque art and sublime rhetoric shared not only the same goal but also the methods by which to achieve it. Both assumed an intense relationship between the composer, their art and the audience. Renaissance art theory had relied on rhetoric to shape its functions too, but whereas the seminal texts of its discourse, such as post-Vitruvian treatises on classical architecture, emphasised the importance of proportion for its own ends, Pseudo-Longinus saw excellence as a quality that went beyond ideal proportion and harmony and was judged on subjective effect rather than empirical rationale.43 The key to Longinian sublimity lay in the relationship between the maker and the one who experienced the work and thus was very much part of the Baroque era in which it was rediscovered, as defined by later scholars such as Heinrich Wölfflin.44

Since the 1950s Baroque art has frequently been described as the visual counterpart to the literature and rhetoric of the Catholic Counter Reformation, most often associated with the Jesuits but prevalent since the rules drawn up by the Council of Trent in the mid-sixteenth century.45 In Italy the function of much Counter Reformation art was not only to persuade the viewer of the power and truth of Roman Catholicism but also, crucially, to move them to become active in their faith, to behave in a certain way.46 Art was perceived as an instrument of rhetoric in that it had the same purpose: to persuade the audience. This it had in common with rediscovered classical expositions on rhetoric and most obviously with Pseudo-Longinus’s essay on the sublime, its own stated aim being to persuade and to move. The ancient treatises did not necessarily specify what the ends of this persuasion were, but concentrated rather on the means. In this sense Pseudo-Longinus’s text could be described as a manual on how to persuade and, indeed, the Jesuits sought to apply its methods to their own purposes.47

The Jesuit brother and artist Andrea Pozzo (1642–1709) produced one of the most celebrated ecclesiastical examples of decorated ceilings at the conventual church of Sant’Ignazio in Rome, the designs for which were detailed in his Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum (1693–1700).48 As the scholar Nicholas Savage has remarked, the text and illustrations of this work ‘are intended to serve as a practical guide to the art of quadratura’ (illusionistic ceiling painting), just as Pseudo-Longinus’s essay is a practical guide to the sublime rhetorical style; moreover, the ultimate aim of each is to affect the audience.49 Pozzo’s own stated aim is to surprise the viewer through illusions – for example, by transforming real architecture through painting – and by perspectival mastery.50 The idea was not to show real architecture according to Vitruvian rules but rather to create an illusion that will have an impact – even an unsettling one – on the viewer looking up from below, as the author reveals in an anecdote about his illusionistic dome:

Some Architects dislik’d my setting the advanc’d Columns upon Corbels, as being a thing not practis’d in solid Structures; but a certain Painter, a Friend of mine, remov’d all their Scruples, by answering for me, That if at any time the Corbels should be so much surcharg’d with the Weight of the Columns, as to endanger their Fall, he was ready to repair the Damage at his own Cost.51

In Sant’Ignazio’s nave ceiling Pozzo uses one point of sight, for which the most advantageous position for the viewer (meaning the most convincing and therefore the most affecting) is marked by a marble disc on the floor of the nave below.52

Pseudo-Longinus says that images – or the visions of a speaker successfully conveyed to an audience – should be surprising in poetry and perspicuous in rhetoric but in both genres they should seek to strike the imagination and move the audience.53 The visual equivalent is evident in Baroque art from around the time that Peri Hypsous was first translated and published in Europe in 1554. Composition for effect was the sine qua non, as it was for Pseudo-Longinus’s sublime rhetoric, and could be achieved through the communication of vivid emotions, the manipulation of perspective or through colour including chiaroscuro (as discussed below). In particular, grand-scale ceiling designs such as Pozzo’s were much developed throughout the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. Increasingly, the designs for ceilings were concerned less with finding a perfect perspective than with manipulating it so as to have the most marked effect on the viewer, partnering history and allegory with a composition designed not only to persuade but also to move. Ceilings especially hijack our senses, blurring the boundaries between the real and imagined worlds, transporting the spectator upwards (sometimes literally, on staircases) through illusionistic architecture into the heavens or else threatening his or her position below with tumbling figures or falling debris. British art theorists such as Richardson echoed Pseudo-Longinus in recognising that to qualify as sublime visual art should aim not merely to please but also to surprise.54Transferred to Britain, primarily by foreign artists in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, decorative history painting became a popular art form. While British schemes were more often conceived for political or domestic interiors than ecclesiastical ones, the ultimate aim – to move the spectator – was common to both Italian and British ceilings.

James Thornhill 1675 or 76–1734

Greenwich Painted Hall ceiling

The Greenwich Foundation for the Old Royal Naval College

Fig.2

James Thornhill

Greenwich Painted Hall ceiling

The Greenwich Foundation for the Old Royal Naval College

Word and image: ‘decorative’ history painting in Britain

The debt that British architects owed to classical writing in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries has been the subject of much scholarship.65 Caroline van Eck has looked specifically at the influence of Pseudo-Longinus’s treatise on Hawksmoor and on architectural commissions more generally.66 The idea that composition was of the utmost importance both in writing and in building design in creating a monumental holistic effect was prevalent in ancient and early modern societies.However, it was the impact of these effects on the spectator that became key to late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century architecture, which frequently rejected perfectly proportioned classical models in the pursuit.

But what of the paintings that were planned alongside the architecture? Both painting and architecture were part of an ensemble and were intended to complement the functions of rooms which, in turn, were often linked to the written or spoken word, whether as libraries or as arenas for diplomatic speech, theatre or even private conversation. The effect is achieved in art in different ways from those in rhetoric but, as Samuel Monk says, the aims and effects themselves are not so different.67 The link between the painted interior and its function is key to understanding its original meaning, and the idea of ut pictura poesis – that painting and poetry could be judged by the same means – was much propounded by art theorists of the time. French artist-theorists including Charles du Fresnoy in De arte graphica (1668) had already paved the way for painting and poetry to be admired by the same criteria.68 The works of the French painter and art critic Roger de Piles were also translated in Britain; he described the ‘grand Gusto’ in painting thus: ‘’Tis by this that ordinary Things are made Beautiful, and the Beautiful, Sublime and Wonderful; for in Painting, the grand Gusto, the Sublime and the Marvellous are one and the same thing. Language indeed is wanting, but everything speaks in a good Picture.’69 Long before this translation, William Sanderson, as discussed above, had put his weight behind the power of art above that of the word. It would be unrealistic, therefore, to imagine that British decorative history schemes were divorced from such debates.

Many British painted ceilings were closely linked with the spoken or written word, either through their narrative scheme or through the importance of speech in their function, for example, as a setting for rhetorical – dramatic or political – performances. This started, arguably, with Rubens’s ceiling in the Banqueting House at Whitehall, installed in 1636, and continued throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.70 In 1668 the now little-known artist Robert Streeter decorated the ceiling of the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford, a space originally intended for staging the public ceremonies of the university.71A year later a paean, or song, to the ceiling was published by Robert Whitehall, who contrasted it favourably with both ancient structures and Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling. The poem has been ridiculed ever since, not only because of its exaggerated rhetoric but crucially because it was seen to overstate the effects of the artwork it described. Nonetheless, some passages reveal important truths about the effects and affects of contemporary ceiling paintings:

These to the life are drawn so curiously

That the beholder would become all Eye:

Or at the least an Argus so sublime

A phant’sie makes essayes to Heaven to climb

That future ages must confess they owe

To STREETER more than Michel Angelo.72

That the beholder would become all Eye:

Or at the least an Argus so sublime

A phant’sie makes essayes to Heaven to climb

That future ages must confess they owe

To STREETER more than Michel Angelo.72

This passage describes the effects of the fantastical imagery on the viewer as being so uplifting and overwhelming that the spectator is consumed by the images, thus paralleling it with the venturing into the heavens shown in the painting. The poem’s dedication also opens up a more general point about the function of contemporary ceiling designs:

Our Theatre, though ’tis

beautifull, in you

Alone it lies to make it vocall, now:

And things inanimate so to inspire

As Orpheus did with his enchanting Lyre.

Your various tongues may teach youth how to please

More than Quintilian or Demosthenes.73

beautifull, in you

Alone it lies to make it vocall, now:

And things inanimate so to inspire

As Orpheus did with his enchanting Lyre.

Your various tongues may teach youth how to please

More than Quintilian or Demosthenes.73

Addressed to the Oxford University chancellor, the poem suggests that in order for the painting to achieve its full inspiring effect it should be pushed to go beyond itself, animated by language. The poem mentions Quintilian and Demosthenes, who were also cited as sublime rhetoricians by Pseudo-Longinus.

Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary about a visit to the house of Streeter, whom he described as ‘the famous history-painter’, where he

found him and Dr. Wren and several virtuosos looking upon the paintings which he is making for the new Theatre at Oxford: and indeed they look as if they would be very fine, and the rest think better than those of Rubens in the Banqueting house at White Hall, but I do not so fully think so. But they will certainly be very noble; and I am mightily pleased to have the fortune to see this man and his work, which is very famous.74

This passage is illuminating because it endows both the painter and his art with a gravitas that we would not necessarily afford them now: it describes Streeter as a painter of ‘histories’ rather than as a ‘decorative’ artist and calls his designs ‘noble’. It reveals, too, that influential figures in the visual arts were impressed by his work – including the architect Christopher Wren. Most importantly, it implies a conscious development of mural painting as a genre in Britain with Streeter proposed as being in serious competition with Rubens’s ceiling at the Banqueting House (only the author himself doubts it).

Louis Chéron 1660–1725

Boughton House Main Hall Ceiling c. 1705–7

Oil on plaster

7.53 x 15.44 m

Collection of The Trustees of the 9th Duke of Buccleuch's Chattels Fund

© Photo Lydia Hamlett

Fig.3

Louis Chéron

Boughton House Main Hall Ceiling c. 1705–7

Collection of The Trustees of the 9th Duke of Buccleuch's Chattels Fund

© Photo Lydia Hamlett

You remember her [the goddess of youth Hebe’s] figure is in the ceiling of my hall at Boughton, which figure some philosophers imagine was formed there by the streams of your toasts daily repeated here, and ascending from the table towards the heavens; which if they had not been stopped by the ceiling, would have formed a better or finer constellation than that of Andromeda, but not being able to make their way through the roof of the Hall they condensed themselves into the figure of Hebe in the ceiling.76

Although used by Murdoch as an example of how attitudes towards such works changed from their original purely allegorical meaning, the letter was written in 1745, a mere twenty years after Chéron’s death, during which time the theory of painting had changed little. The author of the letter not only acknowledges the iconography of the painting but also describes the effect of its composition and in turn links this to the wider function of the room. While Chéron’s subjects are undoubtedly allegorical, he too must surely have considered their effect on the location and their relationship with the spectator. The idea of Stukeley’s spoken words floating heavenwards and being caught just under the ceiling where they transform into a literal figure of speech (rather than travelling further to become stars) is at once flattering to the recipient of the letter and pure fantasia. The passage is extraordinary not only for the ways in which it demonstrates a contemporary concern with linking speech and visual imagery but also because it is closely related to the etymological meaning of the word ‘sublime’, as described earlier, meaning literally ‘under’ or ‘up to’ the ‘lintel’ (in architecture, the height threshold of a building). The idea that words travel upwards to heaven and transform themselves into images is at once sublime and also key to our understanding of the art of this time.

Even the poet Alexander Pope who, as discussed below, led the taste debates of the early eighteenth century in favour of a less flamboyant style of country house decoration, acknowledged that the purpose of painted interiors was to animate the space: ‘Then, from her roof when Verrio’s colours fall, / And leave inanimate the naked wall.’77The Longinian sublime animated everything that it touched, and the strength of painted interiors relied just as heavily on their composition as on their relationship with the room as a space; rather than providing a static allegorical backdrop, they were instead intended to be animated by, and interact with, the activity contained within.

Sublime iconography

Over the course of the seventeenth century, visual representations of apotheosis and the classical gods were brought into the domestic sphere and became major themes of decorative history painting, employed by almost every regal and aristocratic authority in Europe for both private and public commissions.78 The Muses, too, were employed to represent the link between men and the gods. Rather than being viewed as simply allegorical, however, these representations were used for effect as compositional devices. Whether arranged as a figural cornice at the edges of a ceiling (for example, in the Blenheim Saloon ceiling painting by Orazio Gentileschi, transferred to Marlborough House in 1711) or stretching the divide between humans and the gods (such as in the pilasters in Laguerre’s staircase at Petworth House), they were frequently used as the architecture bridging the leap between the earthly and heavenly realms. As such the iconographical themes represent the patron’s own aspirations to greatness and even to immortal recognition. William Sanderson describes the creation of an otherworldliness within the aristocratic house that supports such an assertion: ‘To give a Picture its value, in respect of the use: We may consider, that God hath created the whole universe for Man; the Microcosm whereof, is contracted into each Man’s Mansion House, or Home, wherein he enjoyes the usus-fructus of himself.’79

Louis Chéron 1660–1725

Boughton House State Bedroom Ceiling c.1695

Oil on plaster

7.44 x 6.85 m

Collection of The Trustees of the 9th Duke of Buccleuch's Chattels Fund

Fig.4

Louis Chéron

Boughton House State Bedroom Ceiling c.1695

Collection of The Trustees of the 9th Duke of Buccleuch's Chattels Fund

Francesco Sleter 1685–1775

Grimsthorpe Castle Dining Room Ceiling

Grimsthorpe & Drummond Castle Trust

Photo © Ray Biggs

Fig.5

Francesco Sleter

Grimsthorpe Castle Dining Room Ceiling

Grimsthorpe & Drummond Castle Trust

Photo © Ray Biggs

Pictures become the sides of your Staire-case; when the grace of a Painting invites your guest to breathe, and stop at the ease-pace, and to delight him, with some Ruine ... And a Piece over-head, to cover the Sieling, at the top-landing to be fore-shortened, in figures looking downward, out of the Clouds with Garlands or Cornu-Copias, to bid welcome.84

Assemblies of the gods are common in painted ceilings but some ancient figures, including Apollo, Mercury and Hercules, were particularly popular. They represent divine inspiration, the liberal arts as a route from mortality to immortality, and in Hercules a demi-god whose narrative was often identified with the endeavours of the patron. While these characters scaled the heights of Olympus, those that aimed too high and failed – for example, Phaeton or Icarus – were also frequently represented, perhaps to remind their patrons of the dangers of hubris.85 Euripides’s vivid description of Phaeton driving uncontrollably the chariot of the sun god Helios was used by Pseudo-Longinus as an example of the true spirit of tragedy being conveyed to the receiver: ‘Who would not say that the Soul of the Poet mounted the chariot along with the rider, that it shared as well as in danger, as in rapidity of flight with the horses?’86 On other occasions Pseudo-Longinus uses the metaphor of soaring high both to illustrate the necessity of the attempt in order to become truly great – ‘Height and Grandeur exposes the Sublime to sudden Falls’87 – as well as to warn against arrogance and bombast, as he writes on the importance of learning properly the art of rhetoric: ‘Flights of Grandeur are then in the utmost danger, when left at random to themselves ... Genius may sometimes want the Spur, but it stands as frequently in need of the Curb’; and, on bombast: ‘even in Tragedy ’tis an unpardonable Offence to soar too high’.88

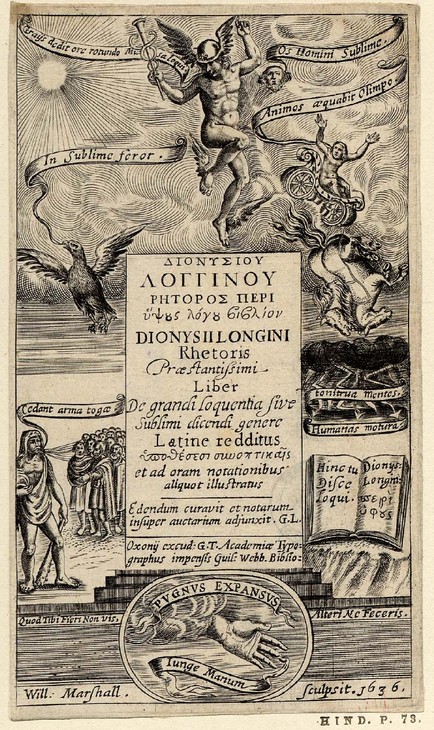

William Marshall

Titlepage to Longinus 'Rhetoris Liber' (Oxford, 1636) 1636

Engraving on paper

127 x 75 mm

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.6

William Marshall

Titlepage to Longinus 'Rhetoris Liber' (Oxford, 1636) 1636

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Sublimity, Protestantism and Britishness

As suggested at the start of this essay, it is the sheer diversity of Jonathan Richardson’s examples of a visual sublime that reveals the ambiguity with which the sublime was viewed in Britain until the second half of the eighteenth century. For as much as Richardson admired surprise and abundance in art – explored above in relation to his choice of Zuccaro’s Annunciation – he also wrote about morality and simplicity as being a part of the creation of the sublime. In his writings on the morally uplifting effects of portraits in the second edition of his Essay on the Theory of Painting (1725) he singled out Van Dyck’s Countess Dowager of Exeter as one portrait in particular that would inspire the spectator to behave better (that is, it had a sublime function). He picked out as another example of the sublime a sketch by Rembrandt of a deathbed scene. These were undoubtedly nods to Pseudo-Longinus, whose writings on the sublime, which Richardson knew well and quoted from directly, highlighted both the power of the sublime to influence our responses and simplicity of composition as being a route to majestic effect. The notion that less could indeed be more mirrored the development of aesthetic judgements during Richardson’s lifetime and the increasing emphasis on artistic clarity for impact. In his apparently confused choice of diametrically opposed artistic styles, Richardson was in fact simply demonstrating the shift in a sublime aesthetic away from its contemporary association with the (Catholic) Baroque style to one that was more suited to (Protestant) Britishness.91

Taste debates

The early eighteenth-century spectator had become increasingly ambivalent towards the effects of decorative history painting. This is reflected in what appears to be a disagreement on the subject in the pages of the daily publication, the Spectator, between its two founders, Richard Steele and Joseph Addison. Steele’s account of his visit to the Painted Hall at Greenwich, quoted above, in which he was clearly greatly moved, has as its epigraph ‘Animum pictura pascit’ (He feasts his soul on the picture), taken from Virgil’s Aeneid.92 Crucially, he omits from the quote the adjective ‘inani’ (empty) used to describe the picture, which Addison had included in an epigraph for one of his own entries in the Spectator four years previously in a famous article on how time improves our appreciation of painting.93 Addison’s piece implied that it was not painting itself that was capable of great impact but only our retrospective view of it, hence his inclusion of the word ‘inani’, meaning empty, lifeless or futile. Steele on the other hand, writing about how Thornhill’s painted ceiling affected his emotions, consciously omitted the adjective thereby leaving us with a quotation that translates as ‘He feasts his soul on the picture’. The context from Virgil of Aeneas looking at a temple frieze that illustrates past glories very much fits in with the conception of Thornhill’s ceiling, which aimed to elevate patriotic feeling and celebrate past glories. By leaving out ‘inani’ we are treated less to a melancholy hankering after the past than to a positive and uplifting celebration of past, present and, it is implied, future British glories.

While here we see two leading intellectuals of the day apparently disagreeing on the powerful effects of state art, there was a wider debate regarding the taste of the nobility. As we have seen, to an extent the Protestant interpretation of the Catholic Counter Reformation aesthetic was translated in British secular art in order to glorify kings and uphold their divine status in public spaces, the two greatest examples being the Banqueting House – executed by the Catholic painter Rubens – and almost a century later Thornhill’s glorification of the Protestant monarchs, William and Mary. In the interim, large-scale architectural painting had been employed by numerous nobles to advertise their own status. However, far from being seen as promoting a sublime style, there were many who deemed such art as crass and purely decorative, and whose criticism undoubtedly contributed to the phasing out of ceiling commissions soon after Thornhill’s work at Greenwich.94 For example, Alexander Pope’s An Epistle to Lord Burlington (1731) mocks the expense paid by various nobles on their country piles, including art, architecture and landscape gardening, and whose oft-quoted words – ‘On painted Ceilings you devoutly stare, / Where sprawl the saints of Verrio or Laguerre, / On gilded Clouds in fair expansion Lie, / And bring all Paradise before your eye’ – appear to poke fun at private chapel decoration as presenting a fantastical, sanitised and frivolous version of religion.95

We have already noted the scornful reaction of some to the effusive description by Robert Whitehall of the Sheldonian Theatre ceiling, and thereafter there was a continuing suspicion among British commentators that large-scale artworks were pompous in their effects and thus reminiscent of Pseudo-Longinus’s descriptions of bombast and the false sublime. There was an increasing sense from critics that the art displayed in aristocratic houses was no longer adequate in terms of its effects and that only nature could have the strength to move us in that most fundamental, sublime sense. The inadequacy of artifice became Pope’s main satirical target: ‘Greatness, with Timon, dwells in such a Draught / As Brings all Brobdignag before your Thought; / To compass this, his Building is a Town, / His pond an Ocean, his parterre a Down.’96 This sentiment is continually echoed thereafter, as emphasised in the famous anecdote in which Dr Johnson remarked on Chatsworth fountain that ‘I am of my friend’s opinion, that when one has seen the ocean, cascades are but little things’.97 These comments are reminiscent of Pseudo-Longinus himself: ‘The Impulse of Nature inclines us to admire, not a little clear transparent Rivulet that ministers to our Necessities, but the Nile ... or still much more, the Ocean.’98 This helps to contextualise the development of a sublime aesthetic relating to the natural object that developed later in the century, but it also reveals something implicit about existing practice: that monarchs and nobles were at least attempting to attain a sublime effect through art and architecture.

William Smith’s On the Sublime, St Paul and Pseudo-Longinus

The Reverend William Smith’s 1739 translation of Pseudo-Longinus is helpful in understanding how a visual sublime was connected with Christian morality by Richardson as well as the more general prevailing practice of appropriating the sublime by British Protestants. Whereas John Hall’s 1652 translation had extolled the powers of good governance and the employment of effective rhetoric during the Commonwealth, Smith’s translation almost a century later reflected the changes since the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the birth of Great Britain in 1707, summarised by the academic William Vaughan as being

based on a Protestant culture, which was seen as providing the basis for free enquiry and commercial success ... set against what was seen as the forces of conservatism and repression, embodied by continental Catholic cultures, in particular that of France.99

In his notes, Smith cited the brave words of William of Orange on fighting the French as an example of sublime rhetoric – that he would ‘Not ... live to see ... [Britain’s] Ruin, but die in the last Dike’ – to illustrate how sparse but carefully worded responses could wield far more power than rambling discourse.100 Whereas the Reverend Zachary Pearce in his 1724 Greek and Latin translation of Pseudo-Longinus had given an ancient Greek example of sublime rhetoric, Smith, in his English translation, related the text to contemporary politics and offered up the example of the Protestant monarch to take on the mantel of the ancients. In his preface and notes, he connected the political circumstances of Pseudo-Longinus’s treatise with contemporary British politics, stressing the importance of liberty and patronage in allowing the sublime to flourish and thereby promoting his anti-slavery stance and also putting the onus of good governance on the latest in the line of Protestant monarchs, George II.101

Smith consistently plays up the link of Pseudo-Longinus to early Christianity in an effort to connect his treatise on the sublime with current religious issues, using Pseudo-Longinus’s knowledge of Fiat Lux as justification. In the notes he picks examples from the New Testament – for example, the Raising of Lazarus – or the psalms with which to illustrate Pseudo-Longinus’s points.102 He stresses that it was God that Pseudo-Longinus urged people to aim for through their actions, ergo promoting Christian morality as a means to attaining the sublime.103 Most significantly, Smith insisted on paralleling Pseudo-Longinus with St Paul, who had been adopted as a patron saint by the British and was often viewed as the counterpoint to St Peter in Rome being similarly at the heart of the capital’s identity through the art and architecture of London’s new cathedral.104 In his preface, Smith directly associates Pseudo-Longinus with St Paul, claiming not only that the ancient writer would have approved of the latter’s rhetorical capabilities in theory but also that he may actually have known his writings.105 By highlighting the fact that both spent time in Athens where they employed the power of the word to great effect – Pseudo-Longinus publishing his treatise there and Paul preaching to the local population – Smith explicitly connects the British patron saint with a classical literary heavyweight. In 1711 Alexander Pope wrote of the classical author:

Smith consistently plays up the link of Pseudo-Longinus to early Christianity in an effort to connect his treatise on the sublime with current religious issues, using Pseudo-Longinus’s knowledge of Fiat Lux as justification. In the notes he picks examples from the New Testament – for example, the Raising of Lazarus – or the psalms with which to illustrate Pseudo-Longinus’s points.102 He stresses that it was God that Pseudo-Longinus urged people to aim for through their actions, ergo promoting Christian morality as a means to attaining the sublime.103 Most significantly, Smith insisted on paralleling Pseudo-Longinus with St Paul, who had been adopted as a patron saint by the British and was often viewed as the counterpoint to St Peter in Rome being similarly at the heart of the capital’s identity through the art and architecture of London’s new cathedral.104 In his preface, Smith directly associates Pseudo-Longinus with St Paul, claiming not only that the ancient writer would have approved of the latter’s rhetorical capabilities in theory but also that he may actually have known his writings.105 By highlighting the fact that both spent time in Athens where they employed the power of the word to great effect – Pseudo-Longinus publishing his treatise there and Paul preaching to the local population – Smith explicitly connects the British patron saint with a classical literary heavyweight. In 1711 Alexander Pope wrote of the classical author:

Thee, bold Longinus! all the Nine [Muses] inspire,

And bless their critic with a poet’s fire.

An ardent judge, who zealous in his trust,

With warmth gives sentence, yet is always just;

Whose own example strengthens all his laws,

And is himself that great sublime he draws.106

And bless their critic with a poet’s fire.

An ardent judge, who zealous in his trust,

With warmth gives sentence, yet is always just;

Whose own example strengthens all his laws,

And is himself that great sublime he draws.106

This idea of a ‘sublime character’, which relied on a commanding presence and rousing rhetoric, was also extended to St Paul himself at this time.107

In Louis Chéron’s frontispiece to Pearce’s 1724 translation of Pseudo-Longinus, the author is depicted lecturing to the Athenians indoors while gesturing to the heavens. However, in John Wall’s frontispiece to William Smith’s 1739 translation, engraved by Gerard Van der Gucht, a similar figure is shown outdoors in the tradition of depictions of St Paul preaching to the Athenians taken from Raphael’s Acts of the Apostles cartoons.108 There is no explicit indication whether the figure represented is St Paul or Pseudo-Longinus, although the use of Pope’s lines quoted above as an epigraph suggests the latter.109 If it is Pseudo-Longinus, but illustrated in the canonical style of St Paul, this suggests a very deliberate merging of the two characters, helping us to see how they were accepted as a pair by the eighteenth-century reader and viewer and the extent to which the Christianising of Pseudo-Longinus, and the sublime, was in fashion. Pseudo-Longinus and St Paul became the figureheads of Smith’s new English translation, suggesting the former as the mouthpiece of the latter and vice versa, figures through which the importance of powerful and morally persuasive rhetoric could be impressed upon the British public.

Smith’s translation also anticipated future aesthetic theories of the sublime. He describes in his notes how the strength of the imagination could only be sparked, but not represented, in art (for example, in the covering up of Agamemnon’s grieving expression in a lost fresco by Timanthes110) and also the contrast between the sublime and the beautiful and the association of the former with terror that was later taken up by Burke and Kant.111 But Smith was also writing at the end of the Baroque era, and his writings above all can help us to explain the shift in interest from a Counter Reformation Baroque sublime to its interpretation on Protestant soil.

Protestant patriotism and the decoration of St Paul’s Cathedral

The reigns of William of Orange and Queen Anne (1650–1707) saw major rebuilding programmes, including many new churches, as well as public art commissions, such as the Painted Hall at Greenwich, which glorified William and his wife Mary in a colourful and dynamic way. As discussed above, the artistic language and composition adopted at Greenwich was chosen to persuade the viewer of the need to believe in and support the Protestant succession, and went hand in hand with the rhetorical literature of the time, such as John Dennis’s patriotic poem about Queen Anne:

And thou, Great Queen, the Glory of thy Sex,

The Prop and Glory of the Noblest Isle;

On whom ev’n William looks admiring down,

And owns thee a Successor worthy him;

On whom the gazing World looks wond’ring up,

And its Deliverance waits from Heav’n and thee,

Whose matchless Piety and watchful Care,

Shews al the wond’ring World that thou are sent

From the bright Church Triumphant in the Sky

To make the warring Church Triumph below.112

The Prop and Glory of the Noblest Isle;

On whom ev’n William looks admiring down,

And owns thee a Successor worthy him;

On whom the gazing World looks wond’ring up,

And its Deliverance waits from Heav’n and thee,

Whose matchless Piety and watchful Care,

Shews al the wond’ring World that thou are sent

From the bright Church Triumphant in the Sky

To make the warring Church Triumph below.112

We have also seen how at this time decorative history painting was not yet deemed impotent or reactionary even though it was not always well received by some intellectuals of the day. Appeals for public history painting in the early 1700s became a political matter and some still called for more Painted Halls; James Ralph, writing in the Weekly Register, even blamed the lack of them on Protestantism. Others such as Addison, however, remained wary of the decorative history paintings of Roman Catholic artists, including Raphael. But Addison was a non-believer in the power of the visual arts, instead putting his trust in the magnificence of God’s natural world, which was to become central to the sublime aesthetic later in the eighteenth century.

Sir James Thornhill 1675 or 76–1734

St Paul Preaching at Athens c.1720

Oil paint on canvas

support: 767 x 512 x 18 mm; frame: 825 x 565 x 26 mm

Lent by the Dean and Chapter of St Pauls Cathedral 1989

On long-term loan to Tate L01486

On long-term loan to Tate L01486

Fig.7

Sir James Thornhill

St Paul Preaching at Athens c.1720

Lent by the Dean and Chapter of St Pauls Cathedral 1989

On long-term loan to Tate L01486

On long-term loan to Tate L01486

In Britain the power of the picture was once again being acknowledged as being as strong, if not stronger, than the word; but perhaps it was only at St Paul’s Cathedral that Protestants found a justifiable type of decorative history painting to rival the grand-scale Catholic Baroque visions. At St Paul’s, Thornhill beat off competition for the commission from foreign artists such as the Jesuit-educated Louis Laguerre.116 During this period the shift in notions of what was visually effective can be seen both in theory and in art practice; the aesthetic choices for the commission at St Paul’s, besides the importance of employing a native Protestant artist, must be seen in this context.117

In Richardson’s chapter on the sublime in the first edition of An Essay on the Theory of Painting (1715) – which is largely taken up by a description of Michelangelo as a sublime artist – he clearly demonstrates his knowledge of Pseudo-Longinus and quotes from the ancient writer, directly applying the rules of his rhetoric to visual art, seemingly without much deliberation.118 For example, he says that the painter should aim to capture the sublime and accept imperfection as part of this, and highlights the importance of surprising and not merely pleasing the viewer. The expanded essay of 1725 is a little more thoughtful, although in parts it is ambiguous about whether the sublime is a term that should be applied wholesale to painting; nevertheless, he defends it thus: ‘The Term indeed is not so Generally apply’d to That Art, but would have been had it been so Generally Understood, and so much treated on as Writing.’119 His confidence appears to have taken a knock, perhaps by the elusiveness of the subject which plagues all scholars of the sublime, or perhaps by criticism of his readiness to apply rhetorical rules directly to painting. Initially, he resorts to generalisations: ‘here I take the Sublime to be the Greatest, and most Beautiful Ideas, whether Corporeal, or not, convey’d to us the most Advantageously.’120 But he soon regains momentum, offering specific examples of the sublime in painting and using Pseudo-Longinus to defend his arguments. In this edition he offers Raphael, rather than Michelangelo, as the pinnacle of achievement. Richardson reiterates once again that ‘a Painter should not Please only, but Surprize’.121

Perhaps what we can most usefully draw from Richardson is how he outlines the shift in the discourse of a visual sublime. His choice of Raphael as the most sublime artist in 1725 is taken by Samuel Monk to epitomise the neoclassical sublime, while the second half of the eighteenth century is dominated by a taste for the wilder, Romantic style of Michelangelo as confirmed by Joshua Reynolds. What is not examined by Monk is why Richardson, in his first edition much earlier in the century, had also chosen Michelangelo as the epitome of a sublime artist and why his opinion had changed by the mid-1720s. This can be explained by a development of taste in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries from a more Baroque sublime – with an admiration for the figures of Michelangelo as agents of human emotion and for the infinite abundance depicted in Zuccaro’s Annunciation fresco – to a more Protestant visual sublime based on simplicity of colour and technique and embodying moral ideas, of which Richardson’s and others’ admiration of Raphael is emblematic.

This shift in taste to a sparser visual sublime is epitomised by Richardson’s choice of a Rembrandt sketch of a dying man as an example of the sublime. Richardson’s admiration for the work is worth recounting in full:

[Rembrandt] has given Us such an Idea of a Death-Bed in one Quarter of a Sheet of Paper in two Figures with few Accompagnements, and in Clair-Obscure only, that the most Eloquent Preacher cannot paint it so strongly by the most Elaborate Discourse; I do not pretend to Describe it, it must be Seen: I will however tell what the Figures, and the rest are. An Old Man is lying on his Bed, just ready to Expire; this Bed had a plain Curtain, and a Lamp hanging over it, for ’tis in a Little sort of an Alcove, Dark Otherwise, though ’tis Bright Day in the next Room, and which is nearest the Eye, There the Son of this Dying Old Man is at Prayers. O God! What is this World! Life passes away like a Tale that is Old. All is over with this Man, and there is such an Expression in this Dull Lamp-Light at Noon-Day, such a Touching Solemnity, and Repose that these Equal any thing in the Airs, and Attitudes of the Figures, which have the Utmost Excellency that I think I ever saw, or can conceive is possible to be Imagined.

’Tis a Drawing, I have it. And here is an Instance of an Important Subject, Impress’d upon our Minds by such Expedients, and Incidents as display an Elevation of Thought, and fine Invention; and all this with the Utmost Art, and with the greatest Simplicity; That being more Apt, at least in this Case, than any Embellishment whatsoever.122

The sketch is profound in its subject, illustrating the last moments of a dying man and the anguish of his son. In its central idea, then, it is sublime. But it is the chiaroscuro, the contrast of light and dark, in the composition that seemingly plays the most affective role, capturing the indefinable transition between life and death. The explanation – that a lack of embellishment can lead to the sublime – is of course reminiscent of Pseudo-Longinus, but Richardson also casts it in a Protestant context: the scene is infused with humble simplicity, more effective than even the most ‘Eloquent Preacher’ could describe, and emphasising the sublimity of domestic prayer. Later, in his 1739 translation of Pseudo-Longinus, William Smith was to give a sermon by Archbishop Tillotson as an example of how we can excel through being moral; and, as we have seen, the frontispiece to Smith appears to parallel a preaching St Paul with Pseudo-Longinus.123 Most important of all, Richardson emphasises that it is the way in which an idea is conveyed that has a profound effect on the mind of the viewer, which is, after all, the true test of the sublime.

The idea that chiaroscuro could be an effective (and affective) medium was not new. Pseudo-Longinus himself had compared the effects of a picture’s all-consuming light to sublime thoughts obscuring rhetorical artifice.124 A parallel is thus made between light and rhetorical sublimity, implying that light is its equivalent in visual terms. William Sanderson took up the cause of the power of art and specifically that of light in his essay in answer to Hall’s translation of Pseudo-Longinus, which emphasised the power of language. Likewise, Roger de Piles, in talking about Rembrandt, observed that the artist ‘drew a great number of Portraits, with Force, Sweetness and Truth or Likeness, that surprise the Spectator ... He touched his Prints over 4 or 5 times, to change the Claro Oscuro, and heighten the effect they had on the Spectator’.125

Thornhill’s commission to paint the interior of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral should be considered in this context. The painting demonstrates the simple yet effective sublime that Richardson describes, and was executed only a few years before his friend’s essay was published.126 In contrast to the Painted Hall at Greenwich, the painted dome relies on light as its central effect. Its impact lies in the stark simplicity of its monochrome chiaroscuro rather than on an abundance of form or colour. In each of the eight scenes that illustrate the life of the cathedral’s patron saint the light comes from the top left, casting shadows in the arches by which each is framed and on the urns which decorate the base of each pier. In place of a central apotheosis or assembly of heavenly creatures, our eyes are raised upwards into the oculus of an illusionistic coffered vault and then into the skylight at the very top, streaming with natural light from its windows. In contrast to those ceilings that ask Pseudo-Longinus’s question ‘When do we most resemble the [pagan] gods?’, it appears rather more to ask, in the mould of Smith’s interpretation of Pseudo-Longinus, ‘When do we most resemble the [Christian] God?’, as it shows the earthly acts of St Paul.

Portraiture

Jonathan Richardson considered the genre of portraiture to be sublime, provided that the sitter’s good character was conveyed successfully enough for it to have an effect on the viewer.127 The moral standing of the sitter was the most crucial ingredient, without which Richardson was convinced that even a painting of the highest quality in terms of technique would, nevertheless, be incapable of rising to the sublime. Ten years previously he had captured what it was about the genre that gave it such power: the connection of the spectator with the sitter. This could potentially be so strong as to move the viewer to act in a better way: ‘Men are excited to imitate the Good Actions, and persuaded to shun the Vices of those whose Examples are thus set before them.’128 This is very much reminiscent of the Longinian interpretation of the sublime, where the audience has such a strong psychological connection with a character that it elevates and inspires them to act in a certain manner. William Sanderson was perhaps referring to Pseudo-Longinus when he said of Van Dyck’s portrait of his wife Maria Ruten, ‘Look upon this Sir, and you shall never sinne’.129 De Piles, who agreed that Van Dyck painted several sublime portraits, said of those of Rubens that ‘The spectator is everywhere mov’d by them, and there are some of them a Sublime Character’.130 Such ideas were later reiterated in John Baillie’s An Essay on the Sublime, published posthumously in 1747: ‘a grave and sedate gesture ... even gives a small degree of Loftiness to the Spectator himself.’131

William Faithorne after Anthony van Dyck

Francesca Bridges Filia Domini Cavendish bet Dotissa Exoniae Comitissa, 1650-63 1650–1663

Engraving on paper

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.8

William Faithorne after Anthony van Dyck

Francesca Bridges Filia Domini Cavendish bet Dotissa Exoniae Comitissa, 1650-63 1650–1663

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Conclusion

Richardson’s crowning of Michelangelo and, later, Raphael as the quintessentially sublime artists hints at a shift in taste between Baroque effusiveness and neoclassical simplicity between the years of publication of the two editions of his essay, 1715 and 1725. The work of Michelangelo was known and admired through his Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes and other works of emotional and religious intensity, including the Cappella Paolina, which Richardson discusses; but the growing popularity of Raphael in Britain seems to epitomise the moral sublimity increasingly favoured by leading British Protestants. The additional example given by Richardson of Zuccaro alongside Rembrandt in 1725 suggests that some vestiges of the Baroque sublime of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries still lingered on in Richardson’s theories. It shows Richardson at the end of an era dominated by the theories of Pseudo-Longinus and not just at the beginning of a more familiar eighteenth-century discourse on the sublime.

Later, Richardson’s and others’ empirical ways of judging the sublime in art appeared inconsequential. However much they had tried to define the sublime there was always something out of their grasp, unquantifiable because, ultimately, affect is subjective. As the scholar Carol Gibson-Wood summarises: ‘the reader [is left] in some doubt as to whether sublimity is a degree of excellence, or the capacity to evoke a distinctive response’.134 History painting was defined by Shaftesbury in neoclassical terms in his Tablature of Hercules (1714), in which he dismissed decorative history painting as being alien, ‘wilder sorts’ of painting. Pope’s Peri bathous (1727) satirised attempts by authors at attaining sublimity in their poetry and, as we have seen, the same kind of criticism began to be levelled at decorative history painters and the patrons who commissioned them to adorn their houses.

By the end of the eighteenth century the sublime had been redefined in aesthetic terms following the publication of Burke’s Philosophical Inquiry in 1757. The ability of increasing numbers of people to travel to places of sublime natural scenery and ancient archaeological sites transformed notions of the effects and affects of art and architecture back home. The admiration of the moral sublime which had, near to the start of the century, replaced an increasingly ridiculed Baroque sublime was itself overtaken by an admiration for the Burkean natural sublime. Samuel Monk describes how a fondness for Raphael and the New Testament in the first half of the century was replaced with one for Michelangelo and the Old Testament in the second half, and how this reflected a renewed keenness for drama, passion and terror.135

What is not examined by Monk is why Richardson had chosen Michelangelo as the epitome of the sublime artist in 1715. An examination of the means of persuasive composition, understood in terms of the Longinian sublime, can help to understand why. All of Richardson’s examples of the sublime in art demonstrate the strong connection between artistic composition and sublimity that had defined the discourse up until that point. Rather than betraying a shallow understanding of the sublime – soon to be overshadowed by a definition based on our relationship with the natural object and the idea that representation was inadequate for communicating the complexity of this experience – Richardson’s writings and case studies reveal the impact of the classical tradition on ideas about art and sublimity. Much of what Richardson viewed as sublime in art – its ability to uplift, the majesty of simplicity and the persuasive power of personality – can be recognised in Pseudo-Longinus’s essay on rhetoric, which clearly shaped the contemporaneous understanding of notions of the sublime, and also goes some way to explaining the seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century experience of visual art.

Notes

On Richardson, see Carol Gibson-Wood, Jonathan Richardson: Art Theorist of the English Enlightenment, New Haven and London 2000; Jonathan Richardson, An Essay on the Theory of Painting, revised edn, London 1725.

The author of this text from approximately the first century ad is unknown, but was attributed to a writer called Longinus when the text was rediscovered due to a note on the manuscript.

These terms will be discussed more fully in due course but can be understood to refer to the emotion that lies behind an action (affect) and an impression produced (effect).

Samuel H. Monk, The Sublime: A Study of Critical Theories in XVIII-Century England, Ann Arbor 1960, pp.1–9, 18–22, 27. See also Alfred Rosenberg, Longinus in England bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts, Berlin 1917.

The term ‘Baroque’ is used here loosely to describe the art of Italy from the late sixteenth to seventeenth centuries and its translations into British visual culture in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. For in-depth discussions of the label see J. Hook, The Baroque Age in England, London 1976, and H. Hills, ed. Rethinking the Baroque, Farnham 2011.

From the original Greek Peri Hypsous it was translated into the Latin De sublimitate, then into English by John Hall in 1652 as On the Height of Eloquence, famously in French by Nicolas Boileau as Du Sublime in 1674, and thereafter, for our purposes, in English as On the Sublime. On the various editions published in England see Monk 1960, pp.19–22. On the early editions, see Bernard Weinberg, ‘Translations and Commentaries of Longinus, On the Sublime, to 1600: A Bibliography’, Modern Philology, vol.47, 1950, pp.145–51; Bernard Weinberg, ‘ps. Longinus, Dionysius Cassius’, in P.O. Kristeller and F.E. Kranz (eds.), Catalogus Translationum et Commentariorum: Mediaeval and Renaissance Latin Translations and Commentaries, Washington, D.C. 1971, pp.193–8; Gustavo Costa, ‘The Latin Translations of Longinus’s Peri hypsous in Renaissance Italy’, Acta Conventus Neo-Latini Bononiensis: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress of Neo-Latin Studies, Binghampton 1985, pp.225–38; Jules Brody, Boileau and Longinus, Geneva 1958, pp.9–13; Marc Fumaroli, ‘Rhétorique d’école et rhétorique adulte’, Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France, vol.86, 1986, pp.35–36, 39–40; Marc Fumaroli, L’École du silence: Le Sentiment des images au XVIIe siècle, Paris 1988, pp.126–9.

Brian Vickers, In Defence of Rhetoric, Oxford 1988, pp.340–74; Caroline van Eck, Classical Rhetoric and the Visual Arts in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge 2007.

Longinus, Dionysius Longinus on the Sublime: Translated from the Greek, with Notes and Observations, and Some Account of the Life, Writings, and Character of the Author, ed. and trans. by William Smith, London 1739, section VII, p.14. Third edition available at http://www.archive.org/stream/dionysiuslongin00smitgoog#page/n74/mode/2up , accessed 14 June 2011.

Longinus 1739, section I, p.3. See also Emma Gilby, ‘The Seventeenth-Century Sublime: Boileau and Poussin’, Tate Papers, issue 13, Spring 2010, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/seventeenth-century-sublime-boileau-and-poussin , accessed 12 September 2012.

The sublime and the beautiful were defined by Burke as two distinct categories; later others, including John Ruskin, did not oppose the two. See Alison Smith, ‘The Sublime in Crisis: Landscape Painting after Turner’, The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language, Tate 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk .

Quoted in Louis Marin, ‘On the Sublime, Infinity, Je Ne Sais Quoi’, in Denis Hollier (ed.), A New History of French Literature, MIT and London 1994, p.341.

For example, ‘[the Sublime] when seasonably addressed, with the rapid force of Lightning has born down all before it, and shewn at one stroke the compacted Might of Genius’. Longinus 1739, section I, p.3, also section XII, pp.33–4; section XX, pp.55–6; section XXIV, p.81. Elsewhere Longinus compares Plato to an ocean, Demosthenes to a thunderbolt and Cicero to a fire; ibid., section XII, p.33, section XIII, p.34.

Marjorie Hope Nicolson, Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite, Ithaca, New York 1959, pp.276–89.

On how rhetoric came to be used by humanists to formulate theories of the visual arts, see Vickers 1988, pp.340–74 and Van Eck 2007, pp.17–30.

John Hall, ‘Dedication’, inLonginus, Dionysius Longinus of the Height of Eloquence, ed. and trans. by John Hall, London 1652. Although Hall does not translate the title as ‘On the Sublime’, he uses the term ‘sublime’ and ‘sublimity’ throughout the text.

Edmond Gayton, ‘Upon our English Zeuxis, W. Sanderson, Esquire’, in William Sanderson, Graphice, London 1658.

The following phrase is especially reminiscent of Longinus: ‘Philosophie was begot, by admiring of Things; Admiration, from the Sight of excellent things; the Mind, raised up and ravished, with the consideration thereof, desirous to know the cause, began to play the Philosopher’. Ibid., p.3.

Longinus, Dionysius Longinus of the Height of Eloquence, ed. and trans. by John Hall, London 1652, section XII; Longinus 1739, section VIII, p.16.

Sanderson 1658, pp.50–1. Later, Richardson gives them as Grace, Greatness, Invention, Expression and Composition. Jonathan Richardson, An Essay on the Theory of Painting, revised edn, London 1725, p.249.

On ‘Fiat Lux’, as well as the political context of John Hall’s writing, see Caroline van Eck, ‘Figuring the Sublime in English Church Architecture 1640–1730’ in Van Eck et al., Translations of the Sublime. On the politics and history of the period and its relation to literature, see David Norbrook, Writing the English Republic: Poetry, Rhetoric and Politics, 1627–1660, Cambridge 2000, and David Norbrook, ‘Milton, Lucy Hutchinson, and the Lucretian Sublime’, Tate Papers, issue 13, Spring 2010, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/milton-lucy-hutchinson-and-lucretian-sublime , accessed 12 September 2012.

Jonathan Richardson, An Essay on the Theory of Painting, London 1715, p.254; Gibson-Wood 2000, p.177.

On Richardson’s collection, see Carol Gibson-Wood, ‘“A Judiciously Disposed Collection”: Jonathan Richardson Senior’s Cabinet of Drawings’, in Christopher Baker, Caroline Elam and Genevieve Warwick (eds.), Collecting Prints and Drawings in Europe c.1500–1750, Aldershot 2003, pp.155–71.

On Federico Zuccaro at Santa Maria Annunziata, see Gauvin A. Bailey, Between Renaissance and Baroque: Jesuit Art in Rome, 1565–1610, London 2003, pp.116–7.

The engravings came from a drawing done specifically for the medium by Zuccaro and then engraved by Cornelis Cort in 1571, later copied by Girolamo Olgiati in 1572 and Raphaël Sadeler in 1580. See Michael Bury, The Print in Italy 1550–1620, London 2001, fig.4, p.74 and nos.74–5, pp.114–16. The chalk study owned by Richardson is now in the British Museum, collection no.1943,1113.24.

Vitruvius’s De architettura, dedicated to Augustus, is the only complete treatise on architecture to survive from classical times. It had an enormous impact from the Early Renaissance on. For more onVitruvius’s impact on early eighteenth-century Britain, see Vaughan Hart with Peter Hicks (eds.), Paper Palaces: the Rise of the Renaissance Architectural Tradition, New Haven 1998.

Heinrich Wölfflin, Renaissance und Barock, Munich 1924. See especially Heinrich Wölfflin, Renaissance and Baroque, trans. Kathrin Simon, London 1984, p.86.

On the Council of Trent, see Hubert Jedin, A History of the Council of Trent, 2 vols., London and New York 1961. On Jesuits and art, see Francis Haskell, Patrons and Painters: A Study in the Relations Between Italian Art and Society in the Age of Baroque, London 1963, especially p.93; Evonne Levy, Propaganda and the Jesuit Baroque, Los Angeles and London 2004, pp.48–52.

Emma Gilby, Sublime Worlds: Early Modern French Literature, London 2006, pp.2–3. See also the work of Maarten Delbeke on Jesuit persuasion in word and image and their adoption of Longinus.

On Pozzo’s frescos at Sant’Ignazio, see Vittorio de Feo and Valentino Martinelli (eds.), Andrea Pozzo, Milan 1996, pp.66–93. On Pozzo, his art, perspective and the Jesuit contribution, see essays by various authors in Alberta Battisti et al., Andrea Pozzo, Milan 1996, especially pp.133–40.

Andrea Pozzo, Rules and Examples of Perspective Proper for Painters and Architects, ed. by John James and illustrated by John Sturt, London 1707, figs.30, 71 and 80.

It was published again c.1725. On the various printed editions of Pozzo, see Savage et al. 1999, pp.1539–48, especially nos.2612 and 2613.

I am grateful to Richard Johns of the Royal Museum, Greenwich, for bringing this to my attention. On John James, see Eileen Harris, British Architectural Books and Writers 1556–1785, Cambridge 1990, pp.242–5.

William Vaughan, British Painting: The Golden Age from Hogarth to Turner, New York 1999, p.111; John Bold et al., Greenwich: An Architectural History of the Royal Hospital for Seamen and the Queen’s House, New Haven and London 2000, pp.145–53.

For example, Roy Strong, ‘Britannia Triumphans’, The Tudor and Stuart Monarchy: Pageantry, Painting, Iconography, vol.3, Woodbridge 1998.

The perspective of Rubens’s ceiling was examined in Joseph Highmore, A Critical Examination of those Two Paintings on the Ceiling of the Banqueting-House at Whitehall, London 1754. For Pozzo on single-point perspective, see Pozzo 1707, fig.100.

Daniel Defoe, A Tour thro‘ the Whole Island of Great Britain, vol.2, London 1725, Letter III, p.8.

For example, Vaughan Hart, Sir John Vanbrugh: Storyteller in Stone, New Haven and London 2008; Caroline van Eck, ‘Longinus’s Essay on the Sublime and the “Most Solemn and Awfull Appearance” of Hawksmoor’s Churches’, Georgian Group Journal, vol.15, 2006, pp.1–7; Van Eck, ‘Figuring the Sublime’.

Rensselaer W. Lee, Ut pictura poesis: The Humanistic Theory of Painting, New York 1967, p.5. See also Jean Hagstrum, The Sister Arts: The Tradition of Literary Pictorialism and English Poetry from Dryden to Gray, Chicago 1958, chapter 1; Mario Praz, Mnemosyne: The Parallel Between Literature and the Visual Arts, Oxford 1970, chapter 1; Vickers 1988, chapter 7; Christopher Braider, Refiguring the Real: Picture and Modernity in Word and Image, 1400–1700, Princeton New Jersey 1993, pp.3–19.

English translation of Roger de Piles, The Art of Painting and the Lives of the Painters, London 1706, p.19.

The precise functions are debated by Simon Thurley in Whitehall Palace: An Architectural History of the Royal Apartments, 1240–1698, New Haven and London 1999.

Anthony Geraghty, ‘Wren’s Preliminary Design for the Sheldonian Theatre’, Architectural History, vol.45, 2002, pp.275–88.

Robert Whitehall, Urania, or a Description of the Painting of the Top of the Theater at Oxon, as the Artist lay’d his Design, London 1669, p.7.

Samuel Pepys, ‘1 February 1668–9’ The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Esq., F.R.S., from 1659 to 1669, with Memoir, ed. by R. Lord Braybrooke, London 1879, p.560.

Many such instances are recorded in contemporary literature that describe the effects of mural paintings in private houses. For example, on Thornhill at Charborough Park, see Christopher Pitt’s poem, ‘To Sir James Thornhill, On his Excellent Painting, the Rape of Helen, at the Seat of General Erle in Dorsetshire’ (1718). I am grateful to Jonathan Yarker for bringing this poem to my attention. Other works of ekphrastic or descriptive literature contain passages that imagine or anticipate the effects of mural paintings on the spectator, such as the poem to Verrio which urges him to decorate the interior of Blenheim Palace, ‘On Her Majesty’s grant of Woodstock Park, &c. To His Grace the Duke of Marlborough’ (1705).

The most comprehensive survey of painted interiors in England is Edward Croft-Murray, Decorative Painting in England 1537–1837, London 1962.